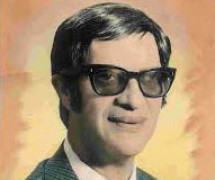

Chico Xavier (1910–2002) was a popular Brazilian medium celebrated for his prolific output of poetry, fiction and Spiritist philosophy, which he said was dictated to him by discarnate spirits.

Early Life

Francisco Cândido (‘Chico’) Xavier was born on 2 April 1910 in Pedro Leopoldo, a small country town in the southern central state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. His father’s only known occupation was that of lottery ticket salesman. One of nine children, his mother died when he was five, after which he was raised by a godmother who is said to have treated him harshly, with frequent beatings.

Shortly after his mother’s death Chico believed he had seen her fully materialized, and by the time he attended primary school, aged eight, he was accustomed to feeling the presence of spirits around him. An early display of the unusual abilities for which he was to become famous occurred when Chico’s class was told to write an essay on the history of Brazil, for a competition run by the state government. He was wondering what to write when he saw a man beside him, who seemed to be dictating, beginning ‘Brazil, discovered by Pedro Alvares Cabral, may be compared to the most precious diamond in the world, which was soon to be set in the crown of Portugal …’

Chico wrote what he claimed to have heard, and much to the surprise of his teacher and classmates, his essay received an honourable mention. Challenged to repeat his feat on a subject chosen by his classmates (‘sand’), Chico wrote on the blackboard: ‘My sons, creation is not mocked. A grain of sand is almost nothing, yet it appears as a tiny star reflecting the sun of God.’

Chico’s formal education ended when he left school aged thirteen to go to work as kitchen hand, shop assistant, and finally clerk in a local branch of the Ministry of Agriculture, where he remained from 1933 until his retirement in 1961.

Literary Beginnings

While still in his teens, Chico continued to believe that he was constantly in touch with the spirit world, notably its deceased poets, and began to write down what he felt they were dictating to him. As he later recalled:

The sensation I always felt when writing [the poems] was that a vigorous hand was propelling mine. Sometimes there seemed to be a non-material volume in front of me where I read and copied them, while at other times it seemed more like somebody dictating them into my ear. I always felt the sensation in my arm of electric fluids around it, the same as in my brain which seemed to have been invaded by an incalculable number of indefinable vibrations. Sometimes this state reached a climax, and the interesting part was that I would seem to have become without a body, not feeling the slightest physical impressions for some time.

Encouraged by a family friend and Spiritist medium Carmen Perácio, he began to send his poems to Spiritist newspapers, which printed them and asked for more. Chico gladly obliged, never receiving nor requesting payment. By 1932 he had amassed enough to fill a book, published in that year by the Brazilian Spiritist Federation under the title Parnaso de além-túmulo (Parnassus from Beyond the Tomb).

The book became a best-seller and is still in print today. Later editions were to contain over 250 poems, some running to several hundred lines, signed by more than fifty authors including some of the leading Brazilian and Portuguese poets of their time. Thirty-one were apparently the work of Augusto dos Anjos (1884–1914) who begins one of his sonnets with this uncompromising affirmation of his identity and continuing existence:

Eu sou quem sou. Extremamente injusto

Seria, então, se não vos declarasse,

Se vos mentisse, se mistificasse

No anonimato, sendo eu o Augusto.I am who I am. It would be extremely unjust

therefore if I did not tell you so,

if I lied to you or mystified you

in anonymity, since I am Augusto.

On a visit to the town of Leopoldina, place of the poet’s birth and death, Chico produced an equally vivid and personal sonnet that ended:

Ajoelha-te e lembra o ultimo abrigo,

Esquece o travo do tormento antigo

E oscula a destra de teus benfeitores.Kneel and recall your last place of refuge,

forget the bitterness of your former torment

and kiss the hand of your benefactors.

Critical Acclaim

Several prominent literary figures expressed their admiration for Chico’s volume. Academician Humberto de Campos declared, after a careful study of the poems in Parnaso that:

their authors were showing the same characteristics of inspiration and expression that identified them on this planet. The themes they tackle are those that preoccupied them when alive. The taste is the same, and the verse generally obeys the same musical flow; loose and ingenuous in Casimiro [de Abreu], broad and sonorous in Castro Alves, sarcastic and varied in Guerra Junqueiro, funeral and serious in [Antero] de Quental, and philosophical and profound in Augusto dos Anjos.

To which author Monteiro Lobato added, ‘if [Chico] produced all this on his own, then he can occupy as many seats in the Academy as he likes’.

Humberto de Campos died soon after Chico’s literary debut, and almost immediately seemed to join his team of discarnate authors. Agripinho Grieco, the leading critic of the time and close friend of Campos, found his postmortem writing to be ‘pure Humberto’, while even a hostile critic, assuming that it must be the work of the devil who just wanted to confuse people, admitted that it was ‘full of the thousand and one technical mannerisms of Humberto’.

Media Interest

In 1935, the prominent newspaper O Globo sent reporter Clementino de Alencar to Pedro Leopoldo to investigate this hitherto unknown writer who had become a literary sensation. After overcoming Chico’s initial reluctance to be interviewed, Alencar did so on several occasions during his two-month stay, during which he filed a total of forty-five articles and attended several sessions at which he was able to watch the medium at work.

He was also able to examine his ‘library’, which consisted of a single shelf stuffed with old magazines, popular almanacs and one or two books on Spiritism that Chico’s admirers had given him. There was, Alencar noted, no poetry – Chico insisted he never read any – and nothing at all by Humberto de Campos. After only a week the reporter had to confess that ‘the possibility of fraud gets more remote all the time'.

Authorship of Books

The medium Carmen Perácio once had a vision in which she told Chico that she saw ‘a shower of books’ pouring down around him, interpreting this as a sign of the mission he was destined to follow. She proved to be right: he went on to write a total of more than 450 books, always insisting that, as he once put it, ‘The books that pass through my hands belong to the Spiritual Instructors and Benefactors, and not to me.’ He never accepted payment for anything he wrote, donating all this royalties to charitable causes.

Chico’s literary output is as notable for its variety as well as for its size. It included novels, both historical and contemporary, stories for children, essays, a constant stream of poems by authors both known and unknown, a history of Brazil (allegedly by the discarnate Humberto de Campos) and numerous works of Spiritist philosophy. Much of his writing was done at public sessions, several of which were filmed showing him at work, his left hand covering his eyes and his right hand filling sheet after sheet of paper at extraordinary speed. More writing was done during Chico’s lunch break when he was working at his day job. Thus there was clearly no time for him to do any research, nor was there any local library where he could have done it.

One of his early novels, set in Rome in the first century, contained such an abundance of details about Rome and its empire that a guide to the historical and geographical references in it ran to 157 pages and contained more than 450 entries. No plausible explanation of how Chico could have acquired such information by conventional methods has yet been given.

Also unexplained was the steady stream of personal messages given to those attending his public meetings, many of whom came in the hope of receiving news from their deceased loved ones. Again and again he would give precise details of their death, usually a premature one, sometimes not only giving the names of members of their family but signing off with nicknames – one young man named Milton ended his message as he used to do when alive with ‘1000 Ton’, the Portuguese word for one thousand being mil. A team of Spiritists from São Paulo managed to track down 45 recipients of such messages, and found that not only was every single statement attributed to the deceased communicators agreed to be accurate, but that much of the information they provided had never been made

Last Years

In 1981 Chico was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize, the petition being signed by over two million Brazilians. More than one undred kilos of documents were flown to Oslo, including details of 64 welfare projects, selected from a total of some two thousand that had benefited from Chico’s royalties. The previous year’s winner, Mother Teresa, had been justly praised for her good work at 28 institutions, whereas Chico had benefited about seventy times as many. One that particularly impressed the Oslo judges was the provision of free childbirth facilities for 100,000 women in just one city (Fortaleza). Even so, the 1981 prize went, for the second time, to the UN High Commission for Refugees, prompting a disappointed critic to note that whereas the UNHCR was only doing what it was paid to do, Chico did what he did voluntarily and for free.

Towards the end of his life, Chico predicted that he would die on a day when Brazil was ‘very happy’. Unlikely as this may have seemed in view of his popularity throughout the country, the prediction came true on 30 June 2002, the day when Brazil won the World Cup for the fifth time. As the country celebrated as only Brazilians can, Chico passed peacefully away with a smile on his face after being told the result.

The people of Uberaba, Chico’s adopted home town since 1958, gave him a funeral befitting a national hero. Some 120,000 of them formed a queue two miles long to file past his coffin, of whom 30,000 joined the funeral procession. Messages of condolence were delivered by the sackful, including one from the then president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who spoke for many when he described Chico as ‘a great spiritual leader loved by the whole of Brazil [who] touched the hearts of all Brazilians who over the years have learned to respect his deep commitment to the well-being of his neighbours’.

In 2010 a special stamp was issued to mark his centenary, and the first of several feature films devoted to his life and work, entitled simply Chico Xavier was seen by two million in its first month.

Automatic Writing or Psychography?

Almost anybody can produce automatic writing, simply by resting a pen or pencil on a blank sheet of paper and waiting until it begins to move on its own, as it very occasionally does, often writing nothing more than abstract squiggles but sometimes producing words and coherent sentences. When more substantial writing is produced, even extending to entire books, it is generally assumed to originate in the writer’s subconscious mind, though since the full extent of our subconscious abilities is unknown, this assumption cannot be definitively proved or disproved. Brazilian Spiritists, however, make a clear distinction between escrita automática (automatic writing) and psicografia (‘psychography’), which they see as communication from a discarnate source or spirit entity.

There is a substantial amount of literature produced by writers while in a dissociated state, who include Coleridge, Blake, Stainton Moses, Andrew Jackson Davis, Thomas Lake Harris, Hudson Tuttle, George Vale Owen, Geraldine Cummins, Frederick Bligh Bond, Pearl Curran and more recently Helen Schucman, author of A Course in Miracles.

Commenting on the impressive output of Pearl Curran (which she attributed to ‘Patience Worth’, an entity for whom there is no historical evidence), Walter Franklin Prince noted that ‘in none of the recognized cases of dissociation has a secondary personality shown power and facility amounting to genius on any field of human endeavor wherein the primary personality has not manifested talent, lavished thought and practice, or even known to cherish ambitions'. She was, he believed, an exception to this rule, and his conclusion would also seem applicable to Chico Xavier:

Either our concept of what we call the subconscious must be radically altered so as to include potencies of which we have hitherto had no knowledge, or else some cause operating through, but not originating in the subconscious of [the medium] must be acknowledged.

Guy Lyon Playfair