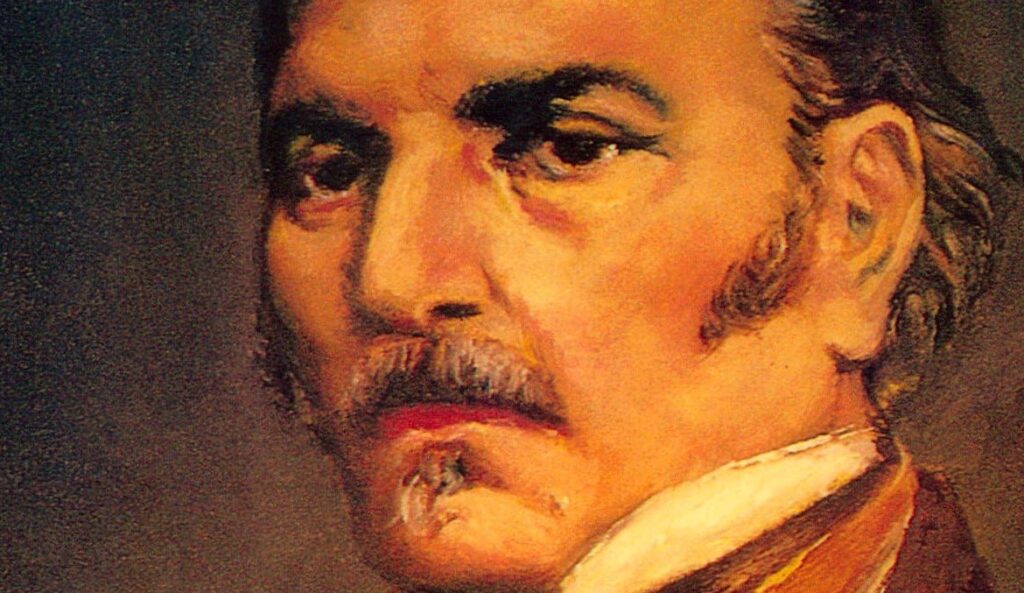

Allan Kardec of France (1804–1869) was an educator and pedagogue who became interested in mediumship later in life. His work with mediums led to the development of Spiritism, a doctrine that embraces after-death communication and reincarnation within a Christian context. Spiritism and its derivatives today have millions of adherents worldwide, notably in Brazil.

Contents

Life

Allan Kardec was the pen name used by Léon-Dénizarth-Hippolyte Rivail, who was born on 4 October 1804 in Lyons, France, to a family prominent in law.1Blackwell (1996). All information in this section is drawn from this source except where noted. From 1815 to 1822 he was educated at the Yverdon Institute in Switzerland, directed by Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, a reformer who favoured the development of a science of education based on fostering independent thought.

Rather than follow his father and grandfather into law, Rivail chose to advance Pestalozzi’s pedagogy in Paris as an educator and author. He wrote some 21 books on education, and schoolbooks on grammar, arithmetic and other subjects, founded schools and worked as a teacher and translator. He was a member of several academic societies including the Royal Academy of Arras, which gave him an award for an essay on education.2Moreira-Almeida (2008).

Rivail began around 1824 to study ‘animal magnetism’, as Blackwell writes, ‘giving much time to the practical investigation of somnambulism, trance, clairvoyance, and the various other phenomena connected with the mesmeric action’.3Blackwell (1996), 11. Initially sceptical of mediumship, he attended sittings by the two young daughters of a friend. Such séances normally produced communications of a frivolous nature, but when Rivail was present the messages reportedly received were serious. When he asked why, he was told that ‘spirits of a much higher order than those who habitually communicated through the two young mediums came expressly for him, and would continue to do so, in order to enable him to fulfill an important religious mission’.4Blackwell (1996), 11.

Rivail composed a series of questions addressing the ‘various problems of human life and the universe’5Blackwell (1996), 11. and submitted them to these spirits through the two young mediums. The answers, received via table raps and planchette, became the basis of the doctrine of Spiritism. With the encouragement of his wife Amélie Boudet, he compiled them in a book which, reportedly by the order of the communicating spirits, he entitled Le Livre des Esprits (The Spirits’ Book). He published it under the pen name Allan Kardec (derived from a name on his mother’s side). Here he introduced the term Spiritism, which he later defined as ‘a science that deals with the nature, origin, and destiny of spirits, and their relation with the corporeal world’.6Kardec (1859/1999), 6. Released in 1857, The Spirits’ Book became a bestseller, creating converts throughout Europe as well as in France. In 1858, the man now best known as Kardec founded the Société parisienne des Etudes spirites (Spiritist Society of Paris) and the monthly Revue Spirite: Journal d’Études Psychologiques (Spiritist Journal: Journal of Psychological Studies), both of which he directed until the end of his life.

Spiritism quickly spread internationally, with groups founding periodicals and sending their own spirit communications to Paris. These were compiled by Kardec in a revised and expanded edition of The Spirits’ Book, which became the recognized Spiritist text. Also from this body of communications he compiled four other Spiritist texts and also wrote two short treatises (see list below).

On 31 March 1869, while in the process of setting up an organization to which he would bequeath the copyright to his writings to ensure the continuation of Spiritism, Kardec died of a ruptured aneurysm. The organizational work was completed by Boudet.

Summary of Spiritist Doctrine

Kardec wrote a series of points that summarized Spiritist doctrine as interpreted by him from the gathered mediumistic data.7Kardec (n.d.), 17-28. They may be summarized as follows.

- God is all-powerful, eternal, good, and the creator of the universe. The universe is divided into the spirit world and the physical world, and the spiritual world preceded the physical, the physical being secondary. Spirits temporarily live in physical bodies. A person is composed of three parts: the physical body, the soul or spirit, and the link between them, termed ‘perispirit’, which is an ethereal body, semi-material, and therefore can sometimes be perceived by the physical senses, that is, heard, seen and touched.

- For this reason humanity has a dual nature: through the body we participate in the nature of animals, by instinct, and through the soul we participate in the nature of spirits. Death destroys the physical body, but the soul and perispirit persist.

- In the spirit world there is a hierarchy of knowledge, purity, love of goodness and closeness to God, with lower order spirits remaining subject to base urges and taking pleasure in evil; between these extremes are average spirits whose interests are trivial.

- All spirits are destined to attain perfection through multiple incarnations in this or other worlds. They can only incarnate in human bodies. Between lives they recall all previous existences. Incarnation is imposed on some spirits as expiation and on others as a mission, as physical life is a trial which acts as a sort of filter, purifying the soul. Successive existences are always progressive, but the rapidity of progress depends on the individual’s efforts to arrive at perfection.

- Spirits are all around us en masse, causing otherwise unexplained phenomena, and should be considered a force of nature. They try to communicate with us either for good or ill, and discerning is easy: good spirits will provide wise counsel akin to that of Christ, adhering to the maxim ‘Do unto others as you would that others should do unto you’, and help us endure the trials of life, whereas bad spirits will manipulate, exploit, tempt to evil, and take pleasure in seeing their victims fall, as it makes us like themselves.

- Spirits communicate in two ways, occult or ostensible. Occult communications are made through good or bad influences on us of which we are unaware, placing the onus on us to distinguish good inspirations from bad. Ostensible communications are made through writing, speech or other physical manifestations, usually through mediums.

- Spirits may manifest spontaneously or in response to evocation, and all spirits may be evoked. We can obtain from them counsels, information about their own situations, their thoughts about us, and other revelations. Good spirits are attracted to people who love goodness and sincerely desire instruction and improvement; bad spirits are drawn by people of frivolous disposition or those who inquire out of mere curiosity.

- Wrongdoing in incarnate life will be punished with exposure, since nothing can be hidden in the spirit world, and the presence of those who one has wronged will be its own punishment. However no sin is unpardonable if the wrongdoer is willing to expiate his errors and seek improvement.

Spiritist Works

Kardec’s textual works on Spiritism have been published and republished many times. In the list below, the embedded links lead to English translations on reliable websites.

- Le Livre des Esprits (The Spirits Book) (1857)

- Le Livre des Médiums (The Book on Mediums) (1861) – ‘a practical treatise on Medianimity and Evocations’8Blackwell (1996), 13. All other book descriptions in this section are also drawn from this source except where otherwise noted.

- L’Évangile selon le Spiritisme (The Gospel According to Spiritism) (1864) – ‘an exposition of morality from the spiritist point of view’

- Le Ciel et L’Enfer (Heaven and Hell) (1865) – ‘a vindication of the justice of the divine government of the human race’

- La Genèse (The Genesis According to Spiritism) (1868) – ‘showing the concordance of the spiritist theory with the discoveries of modern science and with the general tenor of the Mosaic record as explained by spirits’

- Qu’est-ce que le spiritisme? (What is Spiritism?) (1859) – ‘the fundamentals of the Spiritist doctrine and a response to some of the main objections against it’9Kardec (2010). Subtitle.

- Le Spiritisme à sa plus simple expression (Spiritism in is Most Simple Expression) (1862) – ‘a short exposition of spirits’ doctrine and their manifestations’10Kardec (n.d.) Subtitle.

Legacy

Kardec’s work had a strong influence on others interested in mediumship and parapsychology. Astronomer and parapsychologist Camille Flammarion joined Kardec’s Société parisienne des Etudes spirites and became a writing medium, producing manuscripts about stars, planets and comets that were signed ‘Galileo’.11Alvarado (2019).

The year 1919 saw the founding of the Institut Métapsychique International (IMI), a private research foundation founded mainly by Spiritists who had been frustrated by the marginalisation of psychical research by French academia. Among these were Gabriel Delanne and Charles Richet. Equipped with staff and its own building complete with a well-equipped laboratory, the IMI conducted experiments with mediums all over Europe.12Evrard (2017).

Currently Spiritism has adherents worldwide but is most strongly represented in Latin America, especially Brazil, where a 2010 government census showed that more than 3.8 million Brazilians identified as Spiritists. This is most likely due to the influence of Brazilian literary medium and cherished national figure Chico Xavier, who first published his mediumistic poetry in Spiritist newspapers. In 1932 his compilation of poems entitled Parnaso de além-túmulo (Parnassus from Beyond the Tomb) was published by the Brazilian Spiritist Federation. It became a bestseller and is still in print.13Playfair (2015).

Brazilian Spiritism will be the subject of a separate article in the Psi Encyclopedia. An article on Ango-American Spiritualism, which unlike Kardec’s Spiritism, long denied the possibility of reincarnation, is also planned.

Criticism

As an internationally successful spiritual movement, Spiritism was naturally the target of denigration. Some examples:

In a letter Helena Blavatsky, the founder of Theosophy, compared her Spiritist and Spiritualist competitors unfavourably with her own method of acquiring ‘truth’ through mediums. ‘In my eyes,’ she wrote, ‘Allan Kardec and Flammarion, Andrew Jackson Davis and Judge Edmonds, are but schoolboys just trying to spell their A B C and sorely blundering sometimes’.14Blavatsky (1875).

A 1923 book written by metaphysician René Guénon, The Spiritist Fallacy, dismisses several doctrines involving mediumship under the term ‘spiritism’. Quoting the physical medium Daniel Douglas Home, he writes of Kardec: ‘Under the dominion of his energetic will, his mediums were so many writing machines slavishly reproducing his own thoughts. If sometimes the published doctrines did not conform to his desires, he corrected them to his liking.15Cited in Guénon (1923/2004), 31.

Kardec’s work naturally was unwelcome to conventional religious authorities. The Catholic Church’s catechism warns (though it may be using the term in the more general sense, as it decries mediumship generally): ‘Spiritism often implies divination or magical practices; the Church for her part warns the faithful against it’.16Holy See (n.d.). In Brazil, Kardec has been criticized by religious figures including the parapsychology critic Oscar González-Quevedo Bruzón, aka Padre Quevedo.

Film

Kardec is a 2019 dramatized biography which ‘follows the story of Allan Kardec, from his days as an educator to his contribution to the spiritist codification’. See trailer with English subtitles at the link.17ImDb (2019).

Organizations and Resources

International Spiritist Council (English)

Collection of Spiritist resources (Portuguese)

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Alvarado, C.S. (2019). Camille Flammarion. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]

Blackwell, A. (1996). Translator’s preface. In The Spirits’ Book by A. Kardec, trans. by A. Blackwell, 9-16. Rio de Janeiro: Federação Espírita Brasileira, Departmento Editorial.

Blavatsky, H.P. (1875). Some unpublished letters of H.P. Blavatsky: Letter No. 2 (to Hiram Corson, 16 February). [Web page.]

Evrard, R. (2017). Psi research in France. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]

Guénon, R. (2004). The Spiritist Fallacy, trans. by R.P. Coomaraswamy & A. Moore Jr. [Originally published in French in 1923 as L’erreur spirite.] Hillsdale, New York, USA: Sophia Perennis.

Holy See (n.d.). Catechism of the Catholic Church, Part 3, Section 2, Chapter 1, Article 1, line 2117. [Web page on Vatican website.]

IBGE (2010). Censo Demográfico: Tabela 137- População residente, por religião. [Interactive web page in Portuguese: select ‘Espirita’.]

ImDb (Internet Movie DataBase, 2019). Kardec. [Web page.]

Kardec, A. (1999).

. [Originally published 1859.] Philadelphia: Allan Kardec Educational Society. [Web page.]

Kardec, A. (n.d.). Spiritism in its Most Simple Expression: A Short Exposition of Spirits’ Doctrine and Their Manifestations, trans. by Miss Gr. & J.J.T. Leipzig, Germany: Franz Wagner.

Kardec. A. (2010). What is Spiritism? Introduction to Knowing the Invisible World, that is, the World of Spirits, trans. by D.W. Kimble, M.M. Saiz, & I. Reis. [Originally published 1859 in French, Paris.] Brasilia, Brazil: International Spiritist Council.

Moreira-Almeida, Alexander (2008). Allan Kardec and the development of a research program in psychic experiences. Proceedings of the Parapsychological Association & Society for Psychical Research Convention, Winchester, UK, 136-151.

Playfair, G.L. (2015). Chico Xavier. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]