‘Cold reading’ is the name given to a collection of psychological strategies that can be used to simulate a ‘psychic’ reading. This article surveys the methods described by a number of commentators.

Contents

- Introduction

- Expanded Model

- Setting the Stage

- Stock Spiel

- Specific Generalizations

- Specific Trivia

- Barnum-type Statements

- Pigeon-holing

- The Client

- The Problem

- ‘True’ cold reading: Using non-verbal feedback

- Warm reading: using verbal feedback

- Fishing

- Hot Reading

- Why should such readings be successful?

- Literature

- Endnotes

Introduction

The standard sceptical explanation for impressive mediumistic communications is in terms of deceptive practices called ‘cold reading’. For example, in commenting on Gary Schwartz’s 2003 book The Afterlife Experiments, which describes experiments with mediums that are claimed to have produced evidence of postmortem communication, Hyman (2003) comments that ‘the readings he presents […] for his case very much resemble the sorts of readings we would expect from psychic readers in general and cold readers in particular.’ Of medium Rebecca Rosen, Karen Stollznow 1Stollznow (2011). comments ‘like […] many others before her, [she] has her own techniques for cold reading, and possibly hot reading. However, Rosen’s skills are far less impressive than those of cold reading experts.’ Nickell2Nickell (2001, 2010). similarly claims that John Edward’s successful television demonstrations were the result of his skill at cold reading and that Edward was also not averse to gathering information about clients in advance of readings.

Generally, these allusions to cold reading tend to be vague and inconsistent and tend to overestimate the kinds of successes that are possible using some of the basic techniques involved. There are very few systematic descriptions of cold reading methods3Notable exceptions are Hyman (1977), Roe & Roxburgh (2013a, 2013b), Rowland (2002), and Schouten (1993)., and so this essay is intended to provide an overview and to indicate under what conditions each of the different methods can be used, and what kinds of information can (and cannot) be produced by them so that one may be better able to evaluate whether cold reading is a plausible explanation in any given case.

The concept of cold reading is not new, often attributed to WL Gresham’s 1953 work Monster Midway, although Whaley4Whaley (1989) 173. describes it as ‘originally the argot of psychic mediums by 1924 […] from the fact that the customer walks in ‘cold’ — previously unknown to the fortune-teller’. The stratagem was probably first hinted at in the writings of Conan Doyle through the instant face-to-face deductions of Sherlock Holmes, published from 1887. Ray Hyman’s classic account of the effect describes it as ‘a procedure by which a ‘reader’ is able to persuade a client whom he has never met before that he knows all about the client’s personality and problems’.5Hyman (1977), 20.. Unfortunately, this does not give us much insight into the actual process of cold reading, and a perhaps more useful operational definition is given elsewhere by Hyman6Hyman (1981), 428.

The cold reading employs the dynamics of the dyadic relationship between psychic and client to develop a sketch that is tailored to the client. The reader employs shrewd observation, nonverbal and verbal feedback from the client, and the client’s active cooperation to create a description that the client is sure penetrates to the core of his or her psyche.

In practice, the techniques identified as examples of cold reading can vary in form from case to case; from a simple reliance on using statements which are true of most peoplethrough to a broader definition which includes pre-session information gathering about a client (despite this not requiring the reader to come to the reading ‘cold’, which would seem to be the essence of cold reading). Techniques such as ‘fishing’ (to be described later) are regarded as central to some accounts but as separate, supplementary methods by others. There is a real danger that such overliberal and inconsistent application of the term will cause it to lose any explanatory power it has.

There are also clear indications that the cold reading ‘process’ actually consists of a number of discrete and independent strategies. Hyman7Hyman (1981). hints at this when he distinguishes between two ‘types’ of reading — static and dynamic — which exploit quite different psychological mechanisms. The former makes use of commonalities between clients to allow the reader to launch into a stock spiel which should apply equally well to all, whereas the latter depends upon interaction with the client to generate material which is more tailor-made to his or her specific circumstances. An attempt will be made here to identify and characterize the actual techniques brought to bear in cold reading, and to specify their interrelationships. The model which has been developed is informed by (i) a review of extant cold reading publications, and (ii) work with a professional pseudopsychic (defined here as a person who produces information or effects which are claimed to be the result of special psychic abilities, but which are in fact generated through normal means).

There exists a substantial specialist literature describing the techniques involved in setting up as a pseudopsychic, running under titles such as Money-making Cold Reading, Cashing in on the Psychic and Confessions of a Cold Reader. This literature is typically produced to allow the peudopsychic fraternity to share resources and expertise, and is not intended to be generally available. Books are privately published or produced by specialist publishers of magic literature, and tend to be advertized in private circulation magic society catalogues and magazines.

Expanded Model

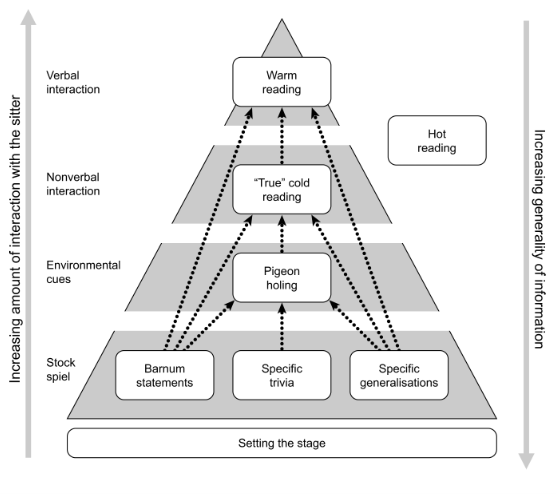

The above sources of information about the pseudopsychic technique suggest a model in which cold reading actually encompasses a number of discrete operations which appear to represent a hierarchy (see Figure 1). All these processes involve the gathering of intelligence about the client but are distinguishable on the basis of when and how transfer of information occurs, and of what form that information takes. Those at the base of the hierarchy require little, if any, interaction with the client, but the reading so-produced remains relatively vague or general and relies on the tendency of the client to interpret the material as personally meaningful. As the opportunity for interaction increases, so the reading can be made more specific to the client in attendance. Knowledge of all of the processes enables the reader to produce a reasonable sketch whatever situation he finds himself in, while being able to be increasingly impressive when circumstances allow.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram representing the hierarchy of reading strategies.

Strategies which appear higher in the pyramid are somewhat dependent upon the use of those lower down for success; however, the reading as a whole does not represent a steady progression through the hierarchy. Rather, the reading is more likely to involve a number of switches from technique to technique depending on the information that is available. For example, if the initial conditions are such that the client immediately offers up personal information, the reader may decide not to begin with lower-order methods of generating material for the reading. In the remainder of this essay I will consider in more detail those strategies which together seem to make up cold reading.

Setting the Stage

An important aspect of the persuasion process is to set the stage for the reading; this includes careful consideration of how the reader presents himself, and how he manages the client’s expectations of the sitting. Its purpose is threefold: to persuade the client that the reader is genuine; to engage the active participation of the client in the reading process; and to provide plausible ‘outs’ should the reading nevertheless not be a success.

The reader works hard, both in terms of presentation and through verbal exchanges, to establish that they are in control of the situation; they emphasize that they have a track record of successful demonstrations so their expertise is not in question — any ‘failures’ must inevitably be placed firmly at the feet of the client. Thus it is already agreed that much of the burden for making the session a success falls on the client:

The reader also emphasizes the co-operative nature of the reading. Messages may come through them which are only meaningful to the client and which cannot be deciphered without their help. Earle8Earle (1990)., for example, notes:

The best readers always include a statement like, ‘I only see pieces, as in a jigsaw puzzle. It is up to you to put them together,’ or, ‘I may speak of a person being crushed by a house as in ‘The wizard of Oz’, but you recognize it as a friend with overdue mortgage payments.’ This attitude has the additional advantage of enlisting the active participation of the client. She is always searching for meanings to your statements and, when she makes the connections, will vividly remember them later.

Although the reader has asserted his expertise, he can use the process of setting the stage to also prepare an ‘out’ should the client not be able to understand elements of the reading, despite much effort — whereas the gift is infallible, the percipient and client are prone to misunderstand its ‘true’ meaning. Underdown9Underdown (2003). describes the pre-show rhetoric for John Edward’s Crossing Over television series as being concerned with lowering audience expectations in this way, explaining that some things the host would say would make sense immediately but that others would not, and might need the recipient to check with family members or undertake further interpretative work to decipher its meaning.

Stock Spiel

A stock spiel reading, also known as a ‘psychological reading’10Hyman (1981). is made up of prepared phrases that can be delivered not only without feedback from the client during the reading, but also without the reader having any contact with her before the session begins. Such statements allow one to give a general description of the client, perhaps including some personal details but without focusing on any specific problems. They are of particular use in situations where the lack of contact will make the reading seem impressive, for example if giving a reading over long distances or while screened from the client. I have assigned the statements that make up a stock spiel into three broad categories: specific generalizations; specific trivia; and Barnum-type statements.

Specific Generalizations

Couttie11Couttie (1988). coined the term ‘specific generalizations’ to describe statements that ostensibly are very specific, but still are meaningful to most people. These items exploit the maxim that we are essentially more alike than different but that we are generally not aware of our similarity. Jones12Jones (1989). effectively characterizes specific generalizations when he states:

Each of us likes to think of ourselves as unique, with problems and needs and goals that sets us apart from all the others. We’re not. Although we may mistrust generalities, whether we like it or not, there is a commonality about our fears, wants, and aspirations that make them predictable […] Psychic readers recognise this, and use it to their advantage.

Couttie even recommends that the reader give the client a general run-down on the reader’s own life-story, hopes and fears, angled as though it was the client’s, in order to illustrate just how impressively accurate this can be. Also included here is the traditional ‘cradle-to-the-grave’ reading, which extends the principle of similarity to suggest that most of us go through the same stages in life, and at roughly the same ages. It has even been suggested that psychics make use of life-span development books for stimulus material, with Gail Sheehy’s book Passages being a common recommendation. As well as going through similar life events to one another, we can also relate to specific but relatively common events, such as the death of an older male with a heart condition, the death of a very young (or unborn) child, a divorce affecting someone the client knows well, and so on.

Wiseman and O’Keeffe13Wiseman & O’Keeffe (2001). refer to this practice in explaining successes during Schwartz’s experiments, noting that many statements that do not appear especially general can nevertheless be true of a surprisingly large number of people. Associating the generalization with something that is unique to the client (for example by presenting it as a concern for a deceased relative) serves to draw attention away from its broad applicability. Dewey and Seville14Dewey & Seville (1984). provide a very useful listing of what they term ‘common themes and specific generalities,’ including that most women have worn their hair much longer or shorter than it is now, have some aches or pains with their feet that are exacerbated by particular shoes they own, feel they are not as photogenic as others, see themselves as romantic despite past experiences, have kept a diary in childhood, and have been badly sunburned at least once.

Blackmore15Blackmore (1997). investigated the suggestion that clients underestimate the likelihood that something that is true for them would also be true for others (and hence can easily be guessed by the psychic), which she terms the ‘probability misjudgement’ theory. In support of this theory, she did find that almost a third of her survey sample of Daily Telegraph readers were willing to agree that each of a number of statements were true of them, including that their back was giving them trouble, they were one of three children, they owned a tape or CD of Handel’s Water Music, they had been to France in the past year, they had a scar on their left knee, and that they had a cat. However, she found that respondents estimated that these things were more likely to be true of others than themselves, contrary to the illusion of uniqueness. More systematic research on this topic would be valuable.

Specific Trivia

Other statements, labelled here as ‘specific trivia’ are so insignificant that they only become memorable if they come true, and even then are impressive by virtue of being true rather than because of what they can say about the client. For example, Anderson often used the prediction that the client would see something in a shop which they would have an urge to impulse-buy, safe in the knowledge that if no such event occurs then the prediction will be forgotten. Martin16Martin (1990). suggests peppering the reading with examples of what he terms ‘out of the blue’ items which touch on: a minor car problem, or some appliance breaking down; strained relationships with someone close; a recent minor hitch in finances; a driver of a green car; and a recent sleepless night. Rowland17Rowland (2002). similarly offers: a box of unsorted old photographs; old medicines well past their use-by date; at least one toy or book kept as a childhood memento; consecutive issues of a magazine no longer subscribed to; and an item of clothing that was bought new but has never been worn.

Use of specific trivia encourages a ‘scatter gun’ approach in which the reader makes a large number of statements in the expectation that at least some will make their mark, and by virtue of their accuracy will be more memorable to the sitter. Stollznow, for example, reports that during a single show, Rosen18Rosen (2011). gave 72 different Christian names, greatly increasing the likelihood that some would be meaningful to audience members.

Barnum-type Statements

Barnum statements are general personality descriptions that apply to almost everyone. Dickson and Kelly19Dickson & Kelly (1985). have defined the Barnum Effect as the tendency for people to accept such statements as accurate descriptions of their own unique personalities. The original Barnum statements were derived by Bertram Forer20Forer (1949). from descriptions he found in news-stand astrology books. The full reading of 13 statements reads as follows:

You have a great need for people to like and admire you. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage. While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them. Your sexual adjustment has caused some problems for you. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety, and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations. You pride yourself as an independent thinker, and don’t accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others. At times you are extraverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved. Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic. Security is one of your major goals in life.

It is claimed that the descriptions are readily accepted because they are sufficiently vague to allow the subject to read into them what they want; indeed, the Barnum effect is so-called in reference to the American showman Phineas T Barnum who is alleged to have attributed the popularity of his circus to there being ‘a little something for everybody,’ a comment which may also apply to Barnum statements themselves.

The phrases recommended by pseudopsychics vary little from those used in the psychological literature to investigate the Barnum Effect21see Roe (1995). and indeed Earle22Earle (1990). actually recommends Forer’s original statements as crib material. It has been consistently found in experimental studies that subjects are willing to accept such statements as being uniquely true of them, and appear unaware of the likelihood that they could apply equally well to others.23see Rosen (2015).

It has been argued that such sketches are effective because they allow the client to read into them what they want. Two mechanisms in particular are thought to be at work: (i) clients will tend to remember only the correct statements; and (ii) clients will interpret statements in a manner that makes them more accurate than they originally were. However, there is little empirical evidence to suggest that clients of psychic readings tend to recall more of the reading elements which they rated as accurate than those items rated inaccurate and much more research is needed to evaluate this assumption.24Roe (1994).

For (ii), it is commonly claimed that subjects will impose their own meaningful interpretation on the statements, embellishing them with their own specific detailed experiences that will make the generalizations seem more accurate than they really were. This can be accounted for in terms of schema theory, which suggests that subjects are likely to unconsciously impose a particular structure on the communication which will invest it with a particular and relevant (to the percipient) meaning. Dean et al.25Dean et al.(1992). describe this tendency as the ‘Procrustean effect’ after the Greek mythical figure who would stretch his guests’ limbs or sever them in order for them to fit his bed. Communications are similarly stretched or truncated to fit the client’s circumstances.

Randi26Randi (1981). gives a nice example of reading more into a reading than was actually said. As a guest on a Canadian TV show he witnessed the psychic Geraldine Smith give the rather vague prediction ‘I’m seeing the month of January here — which is now — but there would have to be something strong with the person with January as well.’ Although skeptical of the reading as a whole, the host of the show noted on reflection that Smith had actually determined that his birthday was in January. In fact no mention had been made of what type of association with January was being referred to — the client was left to fill in the gaps.

Pigeon-holing

Stock spiel statements are necessarily general, even though interpretation by the client is claimed to make them seem more impressive. To provide more specific assertions, the reader must narrow down the number of topic areas which could possibly be relevant by assigning the client to a particular category and generating a stereotype for that sub-population that will inform him of the kinds of interest or concern to concentrate on. Such classification seems to occur along two main dimensions which are somewhat mutually dependent: what type of person the client is, and what type of problem they are concerned with. Pigeon-holing makes use of information leakage which occurs very early in the reading situation and requires little, if any, subsequent feedback.

The Client

The reader classifies the client prior to or very early in the reading by scanning the environment for sources of intelligence about her. The main distinctions are made according to the sex and age of the client, and at one extreme may simply use a narrowed version of the cradle-to-grave reading, or other stock spiel, determined by information given up by the sitter. For example, Couttie27Couttie (1988). describes how:

Up to the age of twenty or twenty-five the main concerns are sex and relationships of different sorts. From then to the mid-thirties the concerns are mainly about jobs, money and the home. For the next ten years there is a shift towards worries about children’s futures, parental health, rethinking careers and so on. From about forty-five onwards there are worries about personal health, one’s own marriage, a desperation about the direction of one’s life, concern about grandchildren and so forth.

Further information can be gleaned from the client’s clothing, physical features, carriage and manner of speech which can point more specifically to their past history and future aspirations. If the reading is held in the client’s home, then themes found in collections of ornaments, pictures, or books will also indicate some hobbies, interests, and aspirations. These will help the reader to assign the client to a narrower and presumably more accurate category. When taken to an extreme, the classification can be quite specific, for example by exploiting the discovery of hobby stickers on cars which indicate membership of particular clubs or societies, or necklaces bearing initials. The reader should not necessarily ignore very obvious sources of intelligence; as Hobrin28Hobrin (1990). notes, ‘you may be surprised to learn the number of people who forget that they are wearing their birth sign or name around their neck. They say familiarity breeds contempt; I’d say that it breeds forgetfulness […] never overlook the obvious.’

The Problem

By pigeon-holing the sitter, and padding out the reading with general statements drawn from the categories described previously, the reader is able to tell her some quite impressive facts about her personality and life history. However, as Jones29Jones (1989) 22. notes, ‘a perception of accuracy is not sufficient to make a reading satisfactory in the minds of most clients’ — the primary function of a reader in most instances is to act as a counsellor.30see Lester (1982), Richards (1990). Clients come to him with a problem for which they seek comfort and advice; even ‘sensation-seeking’ clients will identify a specific problem or question which is uppermost in their minds and wait to see what the reader has to say about it. Strategies intended to determine the client’s problem again rely on the assumption that we are more alike than different. The problems which occur in life belong to a finite (and small) number of categories, each of which has only a limited number of specific problems associated with it, such as love, sex, friendships, money, career, health and travel.

Utilising the population stereotypes noted above allows the reader to assess the probabilities of each problem area being applicable in this case. By ranking them in this way he can quickly deal with each of the most likely worries. By mentioning all of the possible problem categories, he can be sure to have covered the one most relevant, even if only in the most general of terms. This will make the reading seem successful to the client because, according to Jones,31Jones (1989). she ‘will assign immediate significance to any mention […] of her problem or worry, while she will pass over as unimportant other problems or worries […mentioned…] in the same reading.’

‘True’ cold reading: Using non-verbal feedback

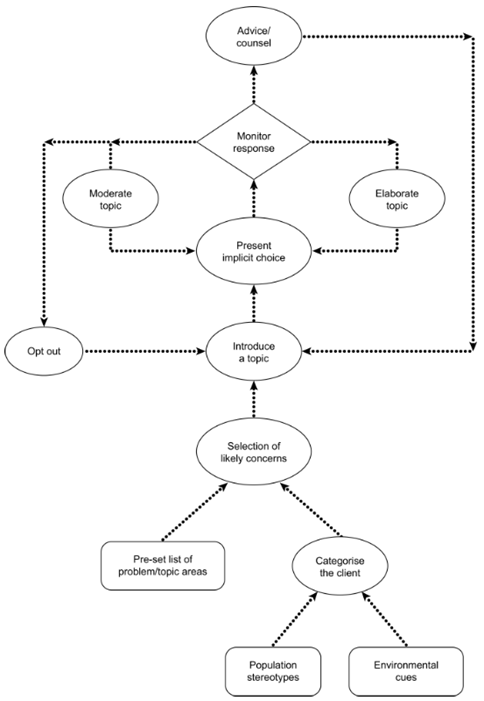

The techniques described up to this point do not exploit information available through interaction with the client but depend instead on general truths and impression formation by the reader. When feedback is available during the reading, there is the opportunity to further refine these categories using what we have termed ‘true cold reading’ (see Figure 2). This process has been likened by Hyman32Hyman (1981). to the Clever Hans phenomenon because it exploits subtle behavioral cues emanating from the questioner during the course of the interaction to arrive at an appropriate reading.

Figure 2. Flow diagram showing how non-verbal feedback is used in cold reading.

It is achieved by introducing each topic (personality characterization or problem area) in a generalized form and noting the client’s behavioral response to its introduction. If it is positive, then the sketch can be elaborated a little further until another choice has to be made and the client is asked to unwittingly provide more feedback which steers the course of the reading. If the response is negative, then the reading is either moderated or the reader may ‘opt out’ back to general categories to try the next one in the list.

When successful, true cold reading can follow a tree-like path, from broad trunk to branch to twig as the implicit choices made non-verbally by the client become more particular, resulting in end points which give very specific information indeed; and the client will tend to only remember this end point, not the stages that led to it. Earle33Earle (1990). illustrates the process by using Barnum statements as his starting point, but goes on to provide alternative elaborations according to the feedback he receives. Greasley34Greasley (2000). uses the term ‘post affirmative boosting’ to describe the elaboration of statements that receive a positive reaction, which he illustrates with the following example:

Medium: I think he would have been a bit hesitant about [spiritualism], wouldn’t he?

Mother: Yes

Medium: He’d have thought it was a load of rubbish wouldn’t he?

Mother: Yes he does

The decision as to how to proceed depends on an ability to ‘read’ the client’s responses to what is being said, exploiting the social conventions that exist for managing a dyadic communication. In normal conversation, the speaker looks intermittently at the listener, especially toward the end of utterances, to determine whether the listener is still interested in what is being said, and to gauge whether the listener wishes to take a turn as speaker. The listener reacts to this cue by producing behaviors that indicate essentially whether they are happy for the speaker to continue, whether they wish the speaker to change the topic of conversation, or whether they wish to take a turn as speaker. These behaviors, known as back-channel signals, can be expressed through a number of modalities. For example, interest is typically indicated verbally through vocalizations including uh-huh’s and similar grunts, facially through smiles, and posturally through head nods, forward or sideways lean and drawing the legs back. Negative reactions can be signalled through frowning, lowing the head or turning the head away, as well as adopting characteristics of a closed posture, such as folded arms. Pseudopsychics can use these (generally unconscious) responses to gauge the appropriateness of what they are saying. In the pseudopsychic literature, commonly recommended measures indicating acceptance include eye blinks, leaning forward, dilated pupils, slight head nod, and blushing. There are fewer signs for negative reactions, possibly since absence of all of the above would be taken as a negative reaction, but the few to be noted in the literature include slight frowning, folding arms, and looking away.

There are likely to be considerable differences between individuals in the way they react to true or false statements. This can be overcome by taking measures of what constitutes a positive and/or negative response before the start of the reading-proper by using questions to which the answer is known or will be given without suspicion. Hobrin35Hobrin (1990). uses an introductory patter with questions like ‘Have you had a reading before?’ and ‘Did any of it come true?,’ which are designed to provide such behavioral benchmarks.

Warm reading: using verbal feedback

The essence of cold reading, then, is the use by the reader of nonverbal feedback from the sitter to help him decide between a number of already-known alternative routes for the conversation. This requires the client unwittingly to deliberate between implicit choices produced by the reader, in what might be termed ‘closed questioning’ (‘do you have children?’). By contrast, in what has been called ‘warm reading’ the emphasis is on the client to provide answers to ‘open questions’ to which the reader need not know the range of possible answers (‘what are your children’s names?’).

Warm reading tends to be opportunistic, with the reader remaining alert to any personal details given up by the sitter at any time during the session from when she enters the room to when she leaves it. Some of this information will be freely volunteered by the client if the reader has successfully developed a rapport with her, through mirroring her body language, appearing friendly and sincere, and expressing a wish to help with her problems. The client can be encouraged to speak — or to continue speaking — by reproducing the back-channel behaviours typically adopted by the listener in conventional conversational dyads. However, this haphazard method is unlikely to naturally produce all the information the reader wants to know. Other data will have to be teased out through ‘fishing’.

Fishing

Hyman36Hyman (1977). defines fishing as ‘a device for getting the subject to tell you about himself,’ but as well as being rather vague, this definition tends to overlook the important characteristic of fishing — that the client doesn’t realize (or at least recall) that she is the supplier of the information. Corinda, for example, describes it as ‘a process of verbal conjuring […in which] you have to make them tell you what they want to know — and yet they must not know they have told you.’

Like cold reading generally, fishing is better defined operationally, and I will consider three versions here. In its crudest form, fishing involves simply asking the client for required information. Lewis,37Lewis (1991). for example, offers the following patter:

Do you drive a red or a silver car? No? Well I see someone close to you who has a car like that. Also, ‘Is there someone around you who wears a uniform? No? You know there are different types of uniform? I think I’m seeing a nurse’s uniform. No? I sense someone bringing you news of some sort, the person bringing the news wears a uniform. You will get benefit from the news, and so will a family member.’

Where the client answers in the affirmative, the reader will be credited with a perspicacious hit. Where unsuccessful, the reader is able to moderate the prediction, for example by widening its applicability, or transforming its meaning altogether. In the above case, the acquaintance in uniform smoothly becomes only the uniformed postman delivering a message from the acquaintance!

More subtly, fishing can involve using questions framed as if they were statements. Here the client is encouraged to elaborate openly on a topic (which of course she has been privately doing for all elements of the reading) as the reader feigns difficulty in quite comprehending the meaning of his message, or is apparently looking for confirmation for a received message. Couttie38Couttie (1988). contrived the following conversation to illustrate how this might work:

psychic: I’m getting something about a car crash?

client: Yes… my brother.

psychic:Because he keeps talking about his shoulder. He’s saying ‘It doesn’t half hurt.’

client: He had head injuries

psychic: That’s right, dear, his head and shoulder are hurting. It was your brother wasn’t it?

client: Yes, that’s right.

psychic: He’s saying ‘I was a fool for not doing up my seat-belt.’ He didn’t do up his seat-belt did he?

client: No he didn’t, that’s right.

psychic: No, we haven’t met before have we? I couldn’t know your brother was in a crash unless I was in contact with him, could I?

The reader’s initial statement is a fairly safe specific generalization, which by the way it is presented stimulates the client to give up information that would be extremely difficult to guess at (that is, that the sitter has a brother who died in a car crash). It is important that the reader gives the impression that whatever information the client volunteers is already known to him. In reality, the reading would be much more chaotic than presented here, as the reader switches between topics and leaves much longer delays between fishing and feeding back the fish. This would increase the likelihood of the client misrecalling that the reader brought up the topic of her brother without any prompting from her.

Another, equally useful form of fishing is the seeking of information about one topic while ostensibly giving information about another. For example, the statement ‘I get the impression that someone close to you, probably someone in the family, was quite ill recently, does that sound right?’ apparently relates to health. In fact the client need only mention a spouse or partner, or son or daughter, for the reader to know that he can safely talk about relationship and family matters. Ideally suited to this purpose are the throwaway items like specific generalizations and specific trivia noted earlier. Once again, such information can be stored away to be presented later in a modified form. To ensure that the client forgets where the details have come from, the reader employs some mis-direction, changing the topic of conversation, usually with the help of predictions derived from stock spiel statements. After a suitable delay the conversation can revert back to the original topic and this ‘new’ information divulged.

Hot Reading

Although most readers don’t generally need to resort to it, information about the client can be gathered in advance of the reading using methods collectively termed ‘hot reading.’ Hyman39Hyman (1997) 405. describes one form of hot reading:

If the reading is through appointment, the reader can use directories and other sources to gather information. When the client enters the consulting room, an assistant can examine the coat left behind (and often the purse as well) for papers, notes, labels, and other such cues about socioeconomic status, and so on.

Lyons and Truzzi40Lyons & Truzzi (1991). illustrate how organized this can be when they list professional and ‘underground’ sources which are often intended for the private detective market but which can be exploited by pseudopsychics. These books run under titles such as How to get anything on anybody and outline methods for locating individuals and finding out about them. Jones41Jones (1989). has devoted whole chapters to describing how information supplied by a prospective client in booking an appointment can give an insight into their circumstances. For example, he lists eleven pieces of information which may be found on a cheque, should the client pay in advance. When presented within the framework of the psychic reading, information derived from these sources can be accurate and specific enough to be very difficult for the client to account for except in terms of the reader’s claimed psychic ability.

Researching one’s clients in advance of a reading has become much easier with the wide availability of the internet and social media. For example, Stollznow42Stollznow (2011). suggests that Rebecca Rosen might have resorted to googling clients or consulting Facebook photographs and other on-line sources of biographical details to gather information about them. With platform or studio demonstrations of mediumship there may be an opportunity to gather information from prospective clients through confederates that can be woven in to subsequent readings. Nickell43Nickell (2001). claims that John Edward may have been using hot reading in this fashion.

Strictly speaking, hot reading should not be included under the banner of cold reading, as on occasion it has been, since it does not entail the reader coming into the reading situation ‘cold’ (knowing nothing about the client in advance). However, when used, the information gained in this way is not baldly given up but is interwoven with information derived from the other strategies to give a broader reading, and so arguably should be included in any model dealing with the interaction of different cold reading strategies.

Why should such readings be successful?

Although the cold reading may be capable of generating quite accurate information, due in part to the client’s effort to find meaning and their tendency to forget what wasn’t true and to embellish what was, it can be argued that this only partly explains the success of the psychic reading. Hyman44Hyman (1981). notes that although it is unlikely that the pseudopsychic reading will generate information which is truly new to the client, it may still have utility for them, as ‘he or she may have a new insight into the conflicts and problems that precipitated the consultation. And new alternatives for coping with the situation may have been opened up.’ Dean45Dean (1986/7). has commented that ‘For every Western astrologer who concentrates on prediction there are probably another two who concentrate on psychology and counselling.’

There may still be a stigma attached to visiting a mental health worker or counsellor, particularly among the working classes; according to Ruthchild46Ruthchild (1981). visiting a psychic may provide a socially acceptable alternative forum for talking through one’s problems and concerns. Pseudopsychics are generally aware of their role as counsellors, and often echo the Hippocratic admonition to ‘first do no harm,’ avoiding offering independent advice but preferring instead to provide non-judgemental support for the decision already reached by the client. One of Gresham’s47Gresham (1953). cold readers explained:

What these poor people need is self-confidence and belief in themselves. If I can give them that, then the dollar or two they pay me is the greatest bargain they’ve ever had. And besides, what most of them need is just a little advice from somebody who’s been around. You’d be surprised some of the things the women tell me that they’d never tell their family doctor. And oftentimes I’m able to set them straight, just by letting them know that other people have the same problems and that they’re not liable to become social outcasts just by having these problems.

Indeed, there is some evidence to suggest that readers can be quite skilled in the art of counselling; Lester48Lester (1982). has noted a number of commonalities between the psychic reading and other more orthodox forms of therapy, which left him impressed with the readers’ competence at the counselling process. Sechrest and Bryan49Bryan (1968). found the advice offered by astrologers to be realistic, and concluded that such consultations were unlikely to be damaging and probably represented a great bargain. Thurstone and Reed50Thurstone & Reed (1984). surprisingly found that psychic readings, given at a distance by anonymous psychics were rated by paying clients as a more valuable source of counselling than more orthodox psychological techniques. This suggests that a reader may be able to provide a valuable service even if his claim concerning the source of his information is untrue. There is great scope to further consider both the interpersonal expertise that the reader may possess, which may contribute to any therapeutic effects, and to determine what criteria the client applies when evaluating the reading. This promises to be a fruitful area for future research.

Chris Roe

Literature

Blackmore, S. (1997). Probability misjudgement and belief in the paranormal: A newspaper survey. British Journal of Psychology 88, 683-89.

Couttie, R. (1988). Forbidden Knowledge: The Paranormal Paradox. Lutterworth Press.

Dean, G.A., Kelly, I.W., Saklofske, D.H. & Furnham, A. (1992). Graphology and human judgement. In The Write Stuff, ed. by B. Beyerstein & D. Beyerstein. 349-95. Amherst, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Dewey, H., & Saville, T.K. (1984). Red Hot Cold Reading: The Professional Pseudo Psychic. In Visible Print.

Dickson, D.H. & Kelly, I.E. (1985). The ‘Barnum Effect’ in personality assessment: A review of the literature. Psychological Reports 57, 367-82.

Earle, L. (1990). The Classic Cold Reading. Binary Star Publications.

Forer, B.R. (1949). The fallacy of personal validation: A classroom demonstration of gullibility. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 44, 118-23.

Greasley, P. (2000). Management of positive and negative responses in a spiritualist medium consultation. Skeptical Inquirer 24/5, 45-49.

Gresham, W.L. (1953). Monster Midway: An Uninhibited Look at the Glittering World of the Carny. New York: Rinehart & Company.

Hobrin (no initial) (1990). Money-making cold reading. Magick Enterprises.

Hyman, R. (1977). Cold reading: How to convince strangers that you know all about them. Skeptical Enquirer 1, 18-37.

Hyman, R. (1981). The psychic reading. In The Clever Hans Phenomenon, ed. by T.A. Sebeok & R. Rosenthal, 169-81. New York: New York Academy of Sciences.

Hyman, R. (2003). How not to test mediums: Critiquing The Afterlife Experiments. Skeptical Inquirer 27/1, 20-30.

Jones, B. (1989). King of the Cold readers: Advanced Professional Pseudo-Psychic Techniques. Jeff Busby Magic Inc.

Lester, D. (1982). Astrologers and psychics as therapists. American Journal of Psychotherapy 36, 56-66.

Lyons, A.. & Truzzi, M. (1991). The Blue Sense: Psychic Detectives and Crime. Mysterious Press

Martin, R. (1990). The Tarot Reader’s Notebook. Flora & Company

Nickell, J. (2001). John Edward: Hustling the bereaved. Skeptical Inquirer 25/6, 19-22.

Nickell, J. (2010). John Edward: Spirit huckster. Skeptical Inquirer 34/2, 19-22.

Randi, J. (1981). Cold reading revisited. In Paranormal Borderlands of Science, ed. by K. Frazier. Amherst, New York, USA: Prometheus.

Richards, D.G. (1990). Exploring the dyadic counseling interaction. Proceedings of Presented Papers: The Parapsychological Association 33rd Annual Convention, 273-88.

Roe, C.A. (1994). Subjects’ evaluations of a Tarot reading. Proceedings of Presented Papers: The Parapsychological Association 37th Annual Convention, 323-34.

Roe, C.A. (1995). Pseudopsychics and the Barnum Effect. European Journal of Parapsychology, 11, 76-91.

Roe, C.A., & Roxburgh, E. (2013a). An overview of cold reading strategies. In The Spiritualist Movement: Speaking with the Dead in America and Around the World: Volume 2, Belief, Practice, and Evidence for Life after Death, ed. by C. Moreman, 177-203. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger.

Roe, C.A., & Roxburgh, E.C. (2013b). Non-parapsychological explanations of ostensibly mediumistic information: A review of the evidence. In The Survival Hypothesis: Essays on Mediumship, ed. by A.J. Rock, 65-78. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Rosen, G.M. (2015). Barnum effect. In The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology, ed. by R.L. Cautin & S.O. Lilienfeld. Hoboken, New Jersey, USA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rowland, I. (2002). The Full Facts Book of Cold Reading (3rd ed.). Ian Rowland Ltd.

Schouten, S. (1993). Applied parapsychology: Studies of psychics and healers. Journal of Scientific Exploration 7, 375-401.

Stollznow, K. (2011). Running hot and cold: “Psychic Medium” Rebecca Rosen. Skeptical Inquirer. [Web page, 26 September.]

Whaley, B. (1989). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Magic. Jeff Busby Magic Inc.

Wiseman, R., & O’Keeffe, C. (2001). A critique of Schwartz et al.’s after-death communication studies. Skeptical Inquirer 25/6, 26-30.