The ‘population problem’ in reincarnation research refers to the argument, first advanced in ancient times, that the continually growing human population proves the impossibility of reincarnation. Several solutions to the problem have been proposed.

History

The early Christian philosopher Tertullian of Carthage (160–222) is the first person known to have addressed the population problem. In his treatise on the human soul De Anima,1Tertullian (n.d./1998). he starts by establishing to his satisfaction that for reincarnation to occur, human population must remain at a fixed number:

The living preceded the dead, afterwards the dead issued from the living, and then again the living from the dead. Now, since this process was evermore going on with the same persons, therefore they, issuing from the same, must always have remained in number the same. For they who emerged (into life) could never have become more nor fewer than they who disappeared (in death).2Tertullian (n.d./1998), Chapter 30.

He then makes a correct case for increasing population in his own era, and concludes that reincarnation therefore cannot occur.

This is only one of many arguments against reincarnation that Tertullian raises in the treatise’s eight chapters. These and writings by other early Christian philosophers arguably played a part in Christianity’s official rejection of reincarnation, decided in 325 at the first Nicean Council, which was convened by the Roman emperor Constantine the Great (274–337).3Matlock (2019), 74. In addition to Tertullian, Matlock also notes that Theophilus of Antioch (d. c .181), Irenaeus of Lyons (d. 202), and Marcus Minucius Felix (d. 260) argued against reincarnation Tertullian’s arguments have been referenced by modern-day sceptics such as Paul Edwards4Edwards (1996), 226-33. and Michael Shermer,5Shermer (2018), 98-99. who assert that reincarnation requires a fixed population number.

Counterarguments

Ian Stevenson, the pioneer of reincarnation research, tackled the population problem in a 1974 paper, pointing out that too many variables are unknown for reincarnation to be ruled out by demographics. He notes that it is possible that intermission lengths in prehistory and early history could have been much longer than they are now. He also suggests that souls might have migrated from non-human animals to humans, or even (in an admittedly science-fictionesque way) from other planets.

Reincarnation researcher James Matlock suggested that new souls might ‘spin off from the godhead’ as required (as stated in Vedanta). Other alternatives, he adds, are preexistence without prior incarnation; or the notion, promoted by the influential German Renaissance rabbi and philosopher Yitzhak Luria, of a soul composed of multiple levels reincarnating independently; or that souls are ‘promoted up the evolutionary line’, as Theosophists believe. Finally, there is the animist conception that ‘spirits may replicate at will’.6Matlock (2019), 111.

Bishai’s Experiment

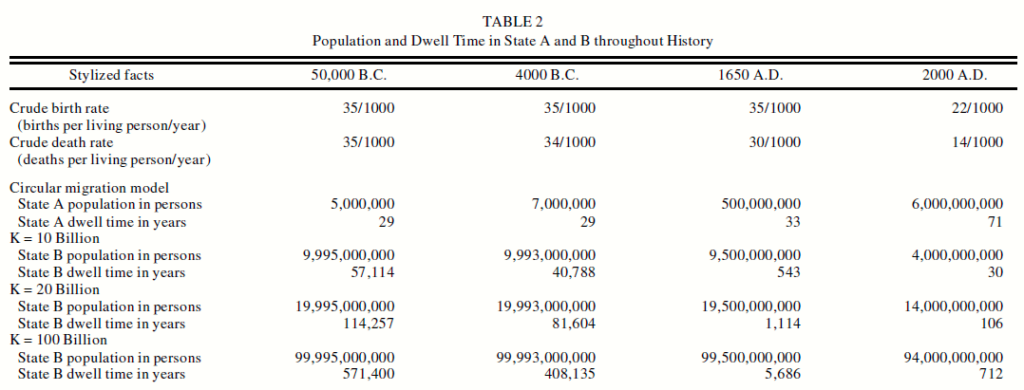

Interested in exploring the mathematics of the population problem, public health professor David Bishai tried computerized calculations and published the results in a paper entitled ‘Can population growth rule out reincarnation? A model of circular migration’ in 2000, ‘circular migration’ referring to the cycling migrations of souls through incarnate and discarnate states.7Bishai (2000). He demonstrated that demographic data cannot be used to refute reincarnation unless one assumes a fixed population of souls (including both incarnate and discarnate) – and not even then if intermission length is variable.

In this excerpt from Bishai’s results table,8Bishai (2000), 418, Table 2. ‘State A’ refers to incarnate existence, ‘State B’ to discarnate existence, or what reincarnation researchers refer to as the intermission. ‘K’ is an assumed fixed population of souls incarnate or discarnate. For a minimum likely soul population, Bishai used the United-Nations-predicted peak of incarnate human population (10 billion); for a maximum, he chose a calculated estimate of number of humans who ever lived since the earliest ritual burial of a homo sapiens (c 50,000 BCE), rounding it to 100 billion. He then calculated State B dwell times, that is, intermission lengths, based on 1) known or estimated birth and death rates; 2) known or estimated human populations and 3) given ‘K’s, that is, soul populations of 10 billion, 20 billion and 100 billion – for the years 50,000 BCE, 4,000 BCE, 1650 CE and 2000 CE. The results are shown in the table.

Discussion

Bishai’s calculations assume there are no existing data on intermission length. However, reincarnation cases in which the previous incarnation is identified, such as the roughly 1,700 collected by Stevenson and other researchers affiliated with the Division of Perceptual Studies, generally include the previous incarnation’s death date and the subject’s birthdate, giving a precise intermission length. From these values, Stevenson calculated a median intermission length of fifteen months for 616 cases. He was also able to discern patterns in intermission length through statistical analysis.

Matlock added to this work. He summarizes his findings here,9Matlock (2017a). For further detail on intermission length see Haraldsson & Matlock (2016), 224-45, Table 26-4. pointing out strong cultural variations in intermission length among other patterns. Culturally, average intermission length ranges from four months in the Haida tribe of northwestern North America to almost twelve years in non-tribal Americans, and more, if American cases published after Stevenson made his calculations are also included.

The intermission lengths that Bishai proposes are much longer: in Bishai’s lowest-population model (10 billion), even the lowest average intermission length (thirty years in the year 2000), while perhaps plausible for an American case, is far above the world median, while the five-figure values for 50,000 BCE and 4,000 BCE are vastly out of range. Thus it is unlikely that a decrease in intermission length can reconcile reincarnation with a fixed number of souls.

In any case, there is no evidence for major change in intermission length over history. To account entirely for the doubling of human population between 1960 (3 billion) and 1999 (6 billion)10World Bank (2018); see graph entitled ‘The world population has increased from 3 billion in 1960 to 7.5 billion today’. average intermission length would have had to decrease by half during the time Stevenson was collecting cases – a fact that he and other researchers would surely have remarked on. Rather, there is some evidence for stability, in that reincarnation accounts in ancient and medieval Eastern sources show many features similar to those investigated by researchers today, including typical Asian intermission lengths of a few years or months.11See Matlock (2017b).

Arguably the most logical and parsimonious solution to the population problem is to assume a continual coming-into-existence of souls. Our presence proves that souls have come into existence at some point, and no reason for this process to have ceased, or evidence for such a cessation, has been offered. As biologist and parapsychologist Michael Nahm writes, ‘We are here already, so why shouldn’t others come and join us?’12Nahm (2023; italics in original.), 160

This model holds important implications for reincarnation theory and belief. It refutes the common belief that everyone has numerous past lives, while supporting the common belief in souls of different ages. In fact it suggests that the vast majority of currently-living people must be relatively ‘new souls’ and that young people especially are likely to be ‘first timers’. A preponderance of new souls might seem to present problems; however, the model does not confirm (or even address) the common belief that old souls are reliably wiser and more spiritually-advanced, any more than age within a life guarantees wisdom or spiritual advancement, so this is probably not a concern.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Bishai, D. (2000). Can population growth rule out reincarnation? A model of circular migration. Journal of Scientific Exploration 14/3, 411-20.

Edwards, P. (1996). Reincarnation: A Critical Examination. Amherst, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Haraldsson, E., & Matlock, J.G. (2016). I Saw a Light and Came Here: Children’s Experiences of Reincarnation. Hove, UK: White Crow Books.

Matlock, J.G. (2017a). Patterns in reincarnation cases. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]

Matlock, J.G. (2017b). Reincarnation accounts from before 1900. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]

Matlock, J.G. (2019). Signs of Reincarnation: Exploring Beliefs, Cases, and Theory. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Nahm, M. (2023). Climbing Mount Evidence: A strategic assessment of the best available evidence for the survival of human consciousness after permanent bodily death. Posted on The 2021 BICS Essay Contest Runners-Up web page, Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies, 2021. In Winning Essays 2023: Proof of Survival of Human Consciousness Beyond Permanent Bodily Death, 108-200. Las Vegas, Nevada, USA: Bigelow Institute for Consciousness Studies.

Shermer, M. (2018). Heavens on Earth: The Scientific Search for the Afterlife, Immortality, and Utopia. New York: Henry Holt.

Stevenson, I. (1974). Questions related to cases of the reincarnation type. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 68, 395-416.

Tertullian of Carthage (n.d./1998), trans. Holmes, P. De Anima [A Treatise on the Soul]. [Web page published on Tertullian.org, derived from the Christian Classics Electronic Library at Wheaton College.]

World Bank (2018). A changing world population. [Web page, published on the World Bank website, 8 October).