Psychische Studien was a German psychical research journal published between 1874 and 1925, containing reports of experiences and investigations of psychic phenomena.

Contents

Psychische Studien (Psychical Studies) was the first psychical research journal in Germany. Inaugurated in 1874, it was published by Oswald Mutze in Leipzig until 1925, then succeeded in the following year by the Zeitschrift für Parapsychologie (Journal of Parapsychology).

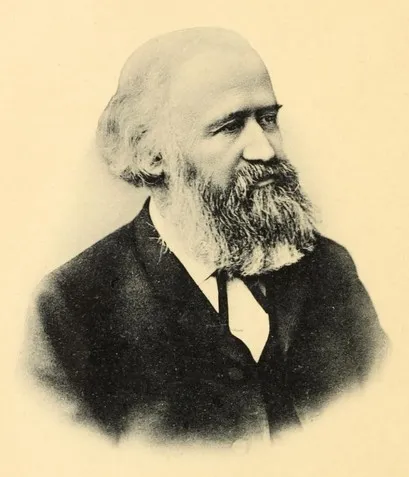

Psychische Studien was founded and financed by Alexander Nikolayevich Aksakov, a former Russian state official who spent much of his time in Europe studying psychic phenomena (he was a cousin by marriage of the noted chemist and convert to spiritualism, Alexander Butlerov). It was edited by Gregor Konstantin Wittig, a Catholic theologian who had been excommunicated.1On Aksakov and the Russian context, see Krementzov (2025) and Mannherz (2012).

Psychology and the Occult

The creation of Psychische Studien in Leipzig foreshadowed the formation of German psychological societies that included psychical research in Munich and Berlin in the 1880s

The journal’s creation can be seen as a first concerted attempt by German-language intellectuals to pursue a more inclusive path to experimental psychology than that proposed by Wilhelm Wundt, who was strongly opposed to claims of psychic experience and aimed to establish experimental psychology on a purely physiological foundation.2See, e.g., Sommer (2013.)

Inaugurating the journal in January 1874, Aksakov wrote:

In our time, where physiological research is pursued with particular zeal, in contrast psychological research is not quite keeping pace. Not infrequently, the latter is only pursued to prove that all psychical phenomena can be reduced to material ones. According to this view, psychology would no longer have the right to exist as a science independent of physiology.3Aksakov (1874), p. 1.

Concerns about the emphasis on physiological research were also voiced by the eminent Austrian philosopher-psychologist Franz Brentano and other anti-reductionist critics. However, most, like Wundt, dismissed the study of spiritualism and occult phenomena out of hand, fearing that to study it seriously would embolden harmful beliefs in a ‘primitive’ supernaturalism. Such beliefs were commonly associated with the Catholic Church, whose immense political grip was being loosened in continental Europe at the time through major political upheavals (although the Church was itself far from sympathetic to psychical research and spiritualism). Leading scientists and philosophers strongly advocated the secularization of political and academic institutions.4On Imperial German occultism, see Treitel (2004). Standard works reconstructing intellectual, cultural, religious and political contexts during the ‘disenchantment’ and attempted

re-enchantment of German science are Gregory (1977) and Harrington (1996).

Aksakov and other early psychical researchers, on the other hand, felt that foundational psychological questions should not be dismissed or pathologized by official science and medicine on a priori metaphysical and political grounds. The maiden issue of Psychische Studien therefore identified such areas of investigations which were shunned and derided by most early university psychologists in Germany:

- Mental phenomena occurring in the waking state, such as illusions, hallucinations, ‘second sight’, premonition and intuition.

- Psychological phenomena occurring in altered states of consciousness: normal sleep (including dreams and visions) and abnormal sleep (including natural and induced somnambulism, hypnosis, ecstasy and other trance phenomena, often associated with mesmerism).

- Physical phenomena occurring in waking and altered states alike, particularly the hotly debated phenomena of spiritualism (movements of objects, levitations, materializations, etc.).

Mirrored by developments particularly in England, Aksakov’s prospectus heralds the formation of a psychological research programme whose methodological tenets came to be adopted – via figures including Carl du Prel in Germany, Charles Richet in France, and FWH Myers and Edmund Gurney in Britain – by the founders of modern university psychology in the US and Switzerland, William James and Théodore Flournoy.

A similar path of research was followed by Carl Gustav Jung in Switzerland, whose MD thesis, On the Psychology and Pathology of so-called Occult Phenomena, partly implemented this alternative programme of psychological investigation.5Jung (1982).

Jung’s MD thesis was printed, incidentally, by the publisher of Psychische Studien, Oswald Mutze.6Another book of significance for historians of psychology and psychiatry published by Mutze is Daniel P. Schreber’s diary recording his mental disturbances, which was famously appropriated by Sigmund Freud, and later translated as Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (Schreber (1903).

A Lens on Hidden Complexities and Continuities

The case of Psychische Studien shows how the views of late-nineteenth scientists and philosophers have been misrepresented through crude historical generalizations.

Analysis of the journal’s early contents challenges persisting interpretations of certain unorthodox scientific activities in terms of simplistic science-versus-religion narratives. Whereas leaders of scientific thought in Germany and elsewhere radically purged science of ‘supernaturalism’ in an effort to liberate politics and academia from clerical inference, both the Catholic and Protestant churches discouraged if not persecuted any sympathetic approach to reported occult phenomena. Aksakov’s transference of activity to Germany, after all, occurred after his study of mediums got him into trouble with the Russian Orthodox Church. And although reliable information about the journal’s first editor, GK Wittig, is hard to come by, it is a fair guess that his excommunication by the Catholic Church was not entirely incidental to his open advocacy of a radical empirical approach to spiritualism.

Moreover, while the journal is still sometimes referred to as a spiritualist magazine, at least under the editorship of Wittig it was fairly pluralistic in outlook. Most crucially in regards to discussions of evidence for postmortem survival, Aksakov was convinced that a residue of mediumistic and other occult phenomena required the assumption of spirits of the dead trying to communicate with the living. Wittig, on the other hand, sided with the philosopher Eduard von Hartmann by advocating the competing view that even the most extraordinary phenomena of spiritualism could be explained through transcendental capacities originating in the unconscious minds of the living.7For the debate concerning interpretations of spiritualist phenomena between Aksakov and the philosopher Eduard von Hartmann, see, e.g., Wolffram (2012).

Topics and Contributors

Particularly during its first decade, the journal was an important conduit for reports of investigations in spiritualism (and resulting controversies) from abroad, by eminent intellectuals and scientists such as William Crookes, Alfred Russel Wallace and Augustus de Morgan in England, and the zoologist Nicolai P Vagner and chemist Alexander Butlerov in Russia.

But it also documents the advocacy of unorthodox science by distinguished German-language intellectuals. Contributors to Psychische Studien included, for example, the Swiss zoologist and anthropologist Maximilian Perty and philosophers such as the renowned Schopenhauer editor Julius Frauenstädt, the famed philosopher of the unconscious Eduard von Hartmann, and Johann Gottlieb Fichte’s son, Immanuel H Fichte.

The younger Fichte’s account of his observations in spiritualism was posthumously published in Psychische Studien in 1879, the year that Wundt founded the first German university institute of experimental psychology in Leipzig.8Fichte (1879).

That year also saw Wundt’s fervent attack on the astrophysicist Karl Johann Friedrich Zöllner for publishing the results of his experiments in spiritualism. The journal closely documents the resulting public controversy, featuring Wundt as plaintiff accusing Zöllner and other eminent Leipzig physicists Wilhelm Weber, Wilhelm Scheibner and Gustav Theodor Fechner (the founder of psychophysics) of undermining the very foundations of German culture, science and religion.9On this controversy, see the entry for Wilhelm Wundt.

In its pages can be found a wealth of original texts and cross-references to publications and news items not covered in standard narratives of the controversy.

By showing that unorthodox scientific activities were not nearly as exceptional or reactionary as popular standard accounts would have it, the example of Psychische Studien calls into question traditional claims of a ‘disenchantment of science’, which has been supposed to characterize if not define modernity.

The journal was eventually renamed Zeitschrift für Parapsychologie in 1926, while continuing to document preoccupations with the ‘occult’ among renowned scientists, medics and philosophers. Its editorial board and authors included well-known psychiatrists and psychologists such as Eugen Bleuler, Enrico Morselli and Gardner Murphy, along with physicists such as Hans Thirring, who collaborated in psychical research with a prominent member of the Vienna Circle of Empirical Positivism, Hans Hahn. Zeitschrift für Parapsychologie ceased publication in 1934.

Public Access

As with several other historical journals and magazines related to the occult published in German, Psychische Studien and Zeitschrift für Parapsychologie can be read and downloaded free of charge on the website of University Library Freiburg.

Andreas Sommer

Literature

Aksakov, A.N. (1874). Prospectus. Psychische Studien 1, 1-6.

Fichte, I.H. (1879). Spiritualistische Memorabilien. Psychische Studien 6, 10-15, 58-68, 107-15, 152-60, 199-206, 337-43, 388-98, 442-52.

Gregory, F. (1977). Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany. (Studies in the History of Modern Science 1). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer.

Harrington, A. (1996). Reenchanted Science: Holism in German Culture from Wilhelm II to Hitler. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

Jung, C.G. (1902). Zur Psychologie und Pathologie sogenannter occulter Phänomene. Eine psychiatrische Studie. Leipzig, Germany: Oswald Mutze.

Krementsov, N. (2025). Alexander N. Aksakov and the domestication of ‘scientific spiritualism’ in Imperial Russia, 1865–1875. Annals of Science (21 April), 1-53. [Epub ahead of print.]

Mannherz, J. (2012). Modern Occultism in Late Imperial Russia. DeKalb, Illinois, USA: Northern Illinois University Press.

Schreber, D.P. (1903). Denkwürdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken. Leipzig: Oswald Mutze.

Sommer, A. (2013). Normalizing the supernormal: The formation of the “Gesellschaft für Psychologische Forschung” (“Society for Psychological Research”), c. 1886–1890. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences 49, 18-44.

Treitel, C. (2004). A Science for the Soul. Occultism and the Genesis of the German Modern. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wolffram, H. (2012). Hallucination or materialization? The animism versus spiritism debate in late-19th-century Germany. History of the Human Sciences 25, 45-66.