Anna Rebello Prado (1883–1923) was a Brazilian spiritist medium reputed to produce direct writing, levitations, apports and materialization phenomena. Her case was investigated by followers of Kardecist spiritism in Brazil. She also attracted the attention of French psychical researchers and spiritualists such as Pascal Forthuny and Gabriel Delanne.

Life

Anna Rebello Prado was born in the Amazonian city of Parintins, probably around 1883 (her exact date of birth is unknown). She was the daughter of Francisco Maximiano de Sousa Rebello and Ermelinda de Carvalho Rebello.

No information is available about Anna’s childhood and adolescence in Parintins. All that is known is that her family was involved with spiritism long before her experiences of mediumship first emerged in 1918. Two of her maternal uncles (Emiliano Olympio de Carvalho Rebello and Jovita Olympio de Carvalho Rebello) held important positions in the Amazonian spiritist movement. Anna’s mother was also acquainted with Allan Kardec’s book The Gospel according to Spiritism.1Magalhães (2012).

In 1901 Anna married Eurípedes de Albuquerque Prado, a businessman, journalist, teacher and politician (he held the position of mayor of Parintins from 1911 to 1913). Eurípedes was raised as Catholic but later adhered to spiritism. As a journalist, he published translations of works by spiritist authors, including Allan Kardec, Léon Denis and Gabriel Delanne, in the Amazonian journal O Tacape. Eurípedes later moved from Parintins with his wife and four children to the city of Belém in the state of Pará, where they began holding spiritist séances.2Magalhães (2012).

Séances

Having read about the phenomenon of turning tables in the spiritist literature, Eurípedes decided to carry out séances in his home with the collaboration of his family. His wife at first refused to participate, doubting that these phenomena were possible, but at his insistence she eventually agreed and was frightened when sudden noises were heard on the table (Eurípedes had been unsuccessful when he had tried earlier with his older children). In subsequent attempts, the table moved and a leg suddenly elevated. By knockings on the table they tried to communicate with the spirit supposedly responsible for the phenomena, receiving the name of a deceased person known to the family. On later occasions the table movements became more intense and household objects were raised up and thrown to the floor. The family named the spirit who manifested itself in this way as João, who then became Prado’s control.3Magalhães (2012).

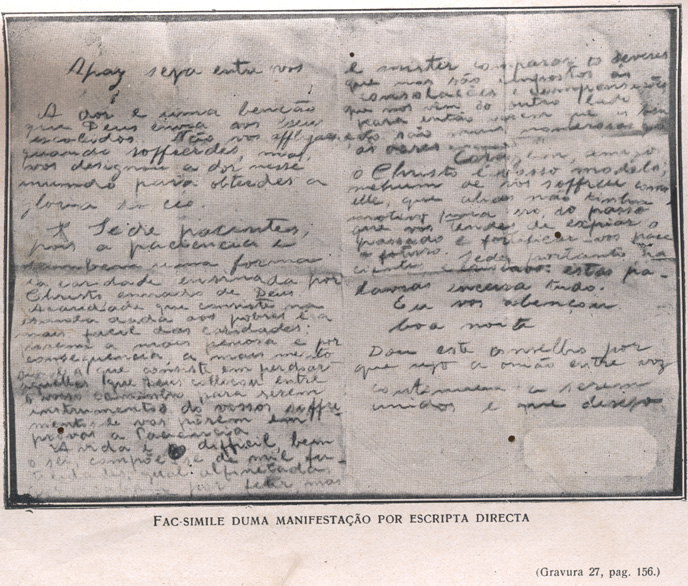

Among the many physical phenomena attributed to Prado’s mediumship were materializations of the dead, apports, levitation of objects, direct writing, typology (alleged communication of spirits through tapping or unusual sounds on tables or other furniture), dematerialization (and subsequent reappearance) of her own body, cutaneous psychography, in which words or entire phrases appeared ‘imprinted’ on her skin, luminous effects, and anomalous germination (incredibly rapid seed germination). During séances, Prado reported alterations in consciousness and visions of spirits. Given the variety of phenomena, the Brazilian spiritist writer Samuel Nunes Magalhães, author of the most comprehensive biography of the medium, ranked her with Eusapia Palladino and Daniel Dunglas Home as one of the most important mediums in the history of psychical research.

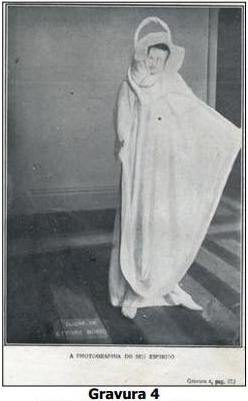

Prado’s séances soon caught the attention of journalists and subsequent newspaper reports led members of the elite of Pará to participate, including physicians, pharmacists, artists, lawyers, and politicians, as well as laypeople. Ettore Bosio, a Brazilian conductor, provided a detailed record of most of these séances and wrote a book entitled O Que Eu Vi (What I Saw). Bosio was the main photographer of the séances; most of the meetings took place at his house. On one occasion, Bosio invited Virgílio de Mendonça, a senator, Antônio Chermont, director of the newspaper O Estado do Pará (The State of Pará) and João Alfredo de Mendonça, journalist and secretary of the newspaper Folha, and asked them to sign their names on the photographic plates before the séance, to guarantee that they would not be exchanged for adulterated copies. Prints were made a few moments after the plates were exposed, in which Bosio was assisted by a professional photographer. Euripides Prado later declared that the photographed figure evidenced the same features of Mr Joaquim Prado, his father, who had died some years before.4Faria (1921).

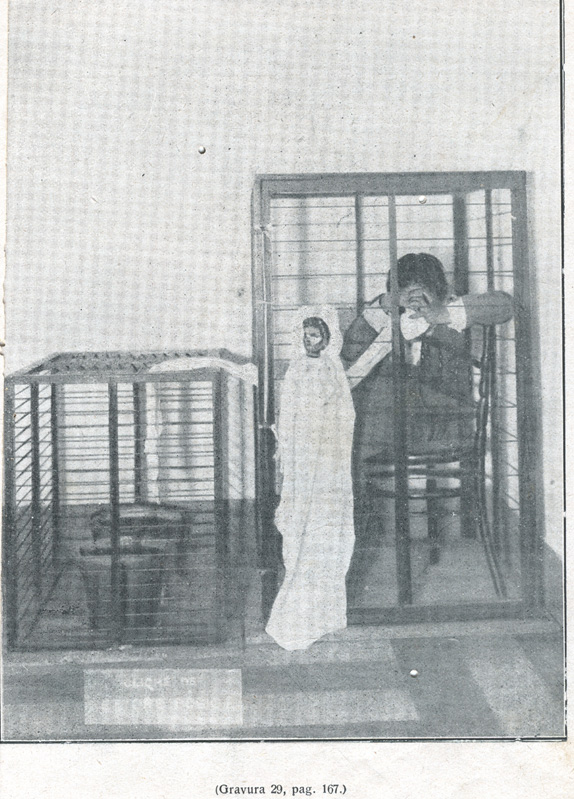

Over time, the attendants added additional controls for fraud in some séances. These included: 1) examination of the room for any evidence of trickery, 2) physical examination of the medium and her clothes, 3) removal of furniture, 4) change of meeting place, and 5) the use of an iron cage to isolate the medium from the audience and differentiate her from the supposed materialized spirits. Commissions were formed to guarantee that experimental controls were observed, with the active cooperation of Prado and her husband were often solicitous. But reports show that she was usually exhausted after the séances and was uncomfortable performing the experiments within the cage. On some occasions, João and the other spirits determined the procedures to be followed: séances were usually carried out under partial or total darkness, allegedly in response to their requests. However, participants were sometimes allowed to touch the materialized figures and to interact with them. Some figures kissed the faces of those present, touched their hands, and even talked with them.5Faria (1921).6Magalhães (2012).

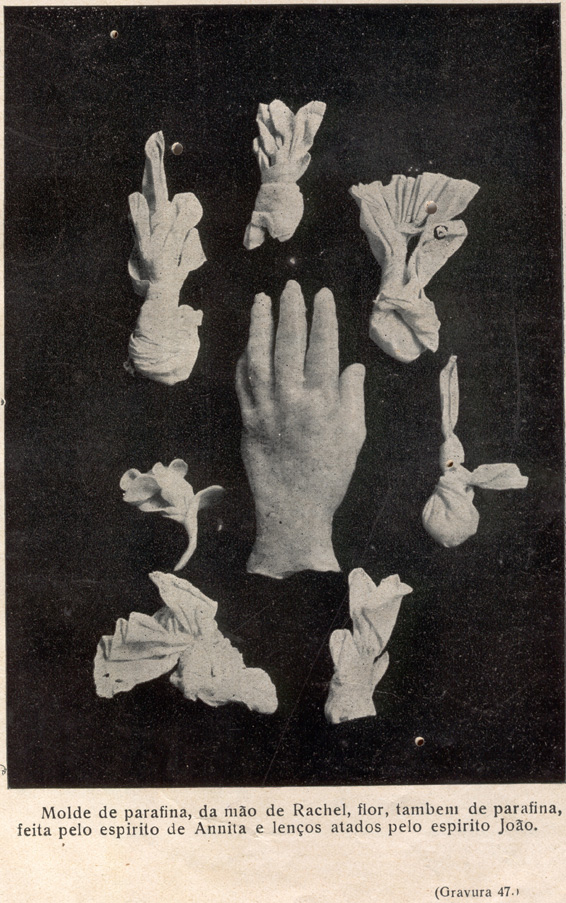

Experiments were made in which the materialized figures placed their hands or feet inside a bucket containing liquid paraffin wax in order to create moulds for plaster casts. Photographs were obtained of these objects. A specimen said to be of the hand of Raquel Figner, deceased daughter of Frederico Figner (past president of the Brazilian Spiritist Federation) and Ester Figner, became part of her family’s private collection (at least until the publication of Magalhães’ book in 2012).

Criticism and Controversy

Like all physical mediums, Prado was often accused of fraud. Her most persistent critic was Florêncio Dubois, a Catholic priest. Dubois claimed that signatures supposed to have been inscribed on the photographic plates before the séances could actually have been made later, and that the plates could have been tampered with before being exposed. Bosio responded by sealing the frame that held the plates and handing it to a journalist, João Alfredo de Mendonça; it was inspected by other attendees prior to the séance and found to be intact;7Faria (1921). he also got the owner of the printing shop to confirm that no evidence of tampering had been found. Other supporting testimonies signed by intellectuals present were collected by Bosio.8Magalhães (2012), 210ff.

That said, some of the photographs are obscure or blurry and their validity would be hard to insist on. Magalhães’s defence of Prado relies heavily on the veracity of the testimonies given by séance attendees of ‘unblemished character and recognized honour’,9Faria (1921). but failed to take into account the limitations of this type of evidence. For example, no suspicions seem to have been aroused when it was found that a message provided by a spirit appeared to have been plagiarized from a passage in a book by Allan Kardec.10Magalhães (2012), 89.

Attempting to demonstrate that the medium and the alleged spirits were different persons, Dr Renato Chaves, a physician, compared her fingerprints with that of the materialized spirit of João. However, the samples were found to be identical. Chaves argued that, if the phenomena observed during the séances were not the result of fraud, they could be nonetheless explained in terms of ‘hypnotism’ or other natural explanation.11Faria (1921). Some newspaper articles tried to explain the phenomena in terms of collective suggestion, as was the case with Gazeta de Notícias.12Magalhães (2012), 285. Such explanations, however, might not cover all the phenomena reported and more investigations would be needed to help understand the many allegations made with regard to Prado’s mediumship.

International Interest

Prado’s mediumship eventually came to the attention of French psychical researchers and spiritualists such as Paschal Forthuny and Gabriel Delanne. Forthuny published two articles briefly describing the case in the Revue Métapsychique,13Forthuny (1922).14Forthuny (1923). published by the Institut Métapsychique International. The first presents the case to the readers, where Forthuny expresses interest in gaining a more detailed medical report on the observed phenomena; in the second, he mentions a letter from Frederico Figner describing the phenomena in more detail. Mentions of Prado are also found in Delanne’s study of reincarnation and in the Revue Spirite, a periodical founded by Allan Kardec.15Magalhães (2012).

Death

Prado was 39-years old when she passed away on April 23, 1923, as a result of burns from an accident with a cooking stove.16Magalhães (2012). Rumours spread by detractors that she committed suicide were denied in by Matta Bacelar, the doctor who attended her.17Faria (1924).

Everton de Oliveira Maraldi

Literature

Faria, R. N. (1921). O Trabalho dos Mortos. Rio de Janeiro: Federação Espírita Brasileira.

Faria, R. N. (1924). Renascença da Alma. Belém: Instituto Lauro Sodré.

Forthuny, P. (1922). Chronique Etrangere: Expériences avec Mme Prado, Médium Brésilien. Revue Métapsychique 1.

Forthuny, P. (1923). Chronique Etrangere: Expériences avec Mme Prado, Médium Brésilien. Revue Métapsychique 2.

Magalhães, S. N. (2012). Anna Prado: A mulher que falava com os mortos. Brasília: Federação Espírita Brasileira.