Anthropologists have long been fascinated by belief in the supernatural, a near universal aspect of human culture. This chronological survey describes many of those who have addressed the topic, from a variety of theoretical and methodological perspectives.

Contents

Pioneers: Primitive Religion and Intellectualism

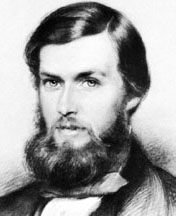

Widely regarded as anthropology’s founding father, EB Tylor (1832–1917) held that belief in spiritual beings was the very minimum definition of religion. He called this belief animism, and suggested that it was from animism that all religious ideas ultimately stemmed.1Tylor (1871).

Tylor maintained that the idea of supernatural beings arose, in the first place, from the misinterpretation of otherwise natural experiences, such as dreaming and other altered states of consciousness. He argued, for example, that early humans might have mistaken their meetings with deceased acquaintances in their dreams as genuine encounters with the disembodied dead. From such experiences, Tylor hypothesized, early humans posited the existence of an immaterial component of the person that could continue to exist after the death of the physical body – the spirit, or soul. Tylor further reasoned that primitive humans expanded this idea to include other aspects of the world: attributing spirits to animals, plants and other natural phenomena such as the wind, lightning, mountains, rivers and the sun, amongst many other objects and phenomena, which often seem to possess a consciousness of their own. These spirits could then be petitioned, propitiated and worshipped, so giving rise (through a gradual process of cultural evolution), to specific deities and the emergence of idiosyncratic religious traditions.2Guthrie (1993).

Tylor’s animistic theory for the origin of religion therefore suggests that supernatural beliefs arise from an attempt to make sense of unusual experiences, and to explain the seemingly conscious activities of animals, plants and other natural phenomena. Such a view essentially naturalizes the supernatural by reducing religion to the misinterpretation of normal cognitive processes, an approach that is still widely employed today.3Tylor (1871). From this perspective, supernatural beliefs represent ‘survivals’ of ‘primitive’, outdated, modes of understanding the world. Interestingly, when Tylor came face-to-face with the anomalous while observing spiritualist mediums he was less quick to offer reductive explanations.4Stocking (1971)..

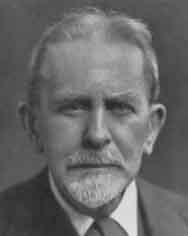

Like Tylor, James Frazer (1854–1941), another of the early anthropological pioneers, also thought of the supernatural as a survival of pre-scientific thought. Indeed, he held that belief in magic was the earliest stage in the development of modern thought, proceeding eventually to religion and then finally to science. Like Tylor, Frazer imagined that early humans, in an effort to control their environment, developed systems of magical belief that provided causal explanations for natural occurrences. For example, by positing the existence of intelligent spirits who controlled nature – and who might be bargained with and manipulated through ritual and sacrifice – they might achieve a desired goal, such as a plentiful harvest, a successful hunt or an end to drought.

The next stage in Frazer’s scheme was the shift from a magical worldview to a religious one, in which the spirits were transformed into more distant deities. Humans might petition and worship, but the deities were ultimately in control. Frazer reasoned that this shift developed as a result of humankind’s inability to affect the forces of nature, which had once been thought of as spiritual agencies.

The final stage, and the development of truly scientific thinking, sees human beings eventually discovering that nature is not governed by intelligent spirits or gods, and realizing that it cannot be bargained with or pleaded to. Rather, nature is found to adhere to immutable natural laws, with science, and the scientific method, being the gradual and systematic discovery of these laws.

For Frazer, supernatural beliefs were essentially a product of delusion and fraud. Belief in the supernatural could be nothing more the a wilful reversion to primitive thinking, in a world clearly governed by impersonal natural laws.5Frazer (1890/1993).

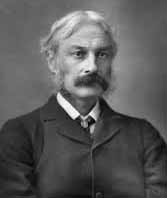

Andrew Lang (1844–1912), a contemporary of both Tylor and Frazer, was the first to combine the research remits of anthropology and psychical research, and to argue for others to do likewise. He called the emerging discipline ‘comparative psychical research,’ a term coined in his 1894 book Cock Lane and Common Sense. In the preface to the second edition of the book Lang expresses his opinion that ‘such things as modern reports of wraiths, ghosts, ‘fire-walking,’ ‘corpse-lights,’ ‘crystal-gazing,’ and so on … are within the province of anthropology’. In the book, Lang bemoans the reluctance of anthropologists to take seriously the kinds of contemporary phenomena investigated by the recently established Society for Psychical Research (SPR), while simultaneously criticizing the SPR for failing to look for comparative data in the anthropological literature.6Lang (2010 [1895]), 9..

Lang therefore proposes comparative psychical research as a bridge between the two disciplines, in which the data of psychical research would be supplemented by similar accounts from different cultural contexts. He argued that this would allow the anomalous data of anthropology to be explained, or at least elucidated, by the findings of psychical research. Even at this early stage in the development of both disciplines, Lang saw the potential for mutual benefits arising from the cross-pollination of theories and findings.

1900–1949: Ethnography

Drawing on his fieldwork amongst the Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea during the First World War, Bronislaw Malinowski (1884–1942) criticised the loftiness and abstraction often ascribed to so-called ‘primitive’ magic and religion by nineteenth century intellectualist theorists like Tylor and Frazer, pointing to the completeness with which belief and practice of magic were embedded in everyday life in Trobriand culture. He writes:

[M]agic and religion are not merely a doctrine or a philosophy, nor merely an intellectual body of opinion, but a special mode of behaviour, a pragmatic attitude built up of reason, feeling, and will alike. It is a mode of action as well as a system of belief, and a sociological phenomenon as well as a personal experience.7Malinowski (1948/1974), 8.

For Malinowski, Frazer’s evolutionary hierarchy, which positioned belief in magic as the most primitive form of human intellectual development, was deeply flawed, for the fundamental reason that magical thinking has not been ‘evolved out’. His own fieldwork in Papua New Guinea suggested that ‘magical’ and ‘scientific’ modes of thought were by no means discrete perspectives on reality; indeed, for the Trobriand Islanders, they were very much complementary. Malinowski observed that where technical knowledge could no longer help, magic was used to ensure success. This was especially evident in the gardening magic of the Trobriand islanders, which sought to ensure fertility and good crops in conjunction with their rational scientific knowledge of gardening techniques. Magic may, therefore, serve important practical functions within a society, and magical thinking need not be thought of as necessarily incompatible with scientific thinking.

In 1926, EE Evans-Pritchard (1902–1973) was commissioned by the British government to discover more about the beliefs and ways of life of the Sudanese Azande. Through a rigorous process of intimate interaction with the Azande over the course of four years, Evans-Pritchard came to an appreciation of the subtleties of Azande cosmology and metaphysics, particularly concerning the way in which the Azande attributed causality to occurrences observed in everyday life.

In addition, Evans-Pritchard noted that the Azande conceived of witchcraft as an ever-present force that connected and explained unfortunate and unusual occurrences. In the context of Azande culture, witchcraft may be thought of as a sort of connecting principle, linking seemingly unexplainable events (somewhat analogous to Jung’s notion of synchronicity, only negative).

Interestingly, Evans-Pritchard had an anomalous experience of his own while immersed in this cultural context. He writes of an unusual encounter that occurred late one night when he was writing up field notes in his hut:

About midnight, before retiring, I took a spear and went for my usual nocturnal stroll. I was walking in the garden at the back of the hut, amongst banana trees, when I noticed a bright light passing at the back of my servant’s hut towards the homestead of a man called Tupoi. As this seemed worth investigation I followed its passage until a grass screen obscured the view. I ran quickly through my hut to the other side in order to see where the light was going to, but did not regain sight of it. I knew that only one man, a member of my household, had a lamp that might have given off so bright a light, but next morning he told me that he had neither been out late at night nor had he used his lamp. There did not lack ready informants to tell me that what I had seen was witchcraft. Shortly afterwards, on the same morning, an old relative of Tupoi and an inmate of his household died. This fully explained the light I had seen. I never discovered the real origin, which was probably a handful of grass lit by someone on his way to defecate, but the coincidence of the direction along which the light moved and the subsequent death accorded well with Zande ideas.8Evans-Pritchard (1937/1976), 11.

To the Azande, the phenomenon witnessed by the anthropologist was witchcraft-substance, a mysterious viscous fluid believed to reside inside the body of witches, externalised and sent on murderous midnight errands. In seeking a normal explanation Evans-Pritchard rejected the Azande interpretation, although he clearly understood the significance of such experiences within the Zande world-view.

Later, in his book Theories of Primitive Religion (1965), Evans-Pritchard clarified somewhat his perspective on the methodological position of the ethnographer in relation to the existence of supernatural entities:

As I understand the matter, there is no possibility of knowing whether the spiritual beings of primitive religions or of any others have any existence or not, and since that is the case he cannot take the question into consideration.9Evans-Pritchard (1965/1972), 17.

In other words, anthropologists should not be concerned with reality-testing the beliefs of their informants; instead they should focus on the observable social effects and functions of belief. This kind of agnostic bracketing would become the standard position for ethnographers who come up against the question of the ontological reality of the supernatural beliefs they study, but one with increasingly obvious limitations.10Northcot (2004), 85-98.

Although not technically an anthropologist, the Belgian-French explorer Alexandra David-Neel provides a unique account of Tibetan mystical beliefs, and her book Magic and Mystery in Tibet must be regarded as a pioneering work in the ethnographic investigation of the paranormal. In the mid-1920s, David-Neel arrived in Lhasa in Tibet, at a time when foreigners were not permitted to enter the city, determined to learn the ways of the Tibetan Buddhist Lamas. She eventually became a Lama herself, the first European to do so. While in Tibet, David-Neel bore witness to a wide variety of seemingly miraculous occurrences, and went so far as to herself attempt to conjure a Tulpa, or thought-form, in the shape of a European monk. In the preface to the 1965 edition of the book, David-Neel drew attention to the difficulties associated with classifying extraordinary phenomena in different cultural contexts when she wrote that:

[T]he Tibetans do not believe in miracles, that is to say, in supernatural happenings. They consider the extraordinary facts which astonish us to be the work of natural energies which come into action in exceptional circumstances, or though the skill of someone who knows how to release them, or, sometimes, through the agency of an individual who unknowingly contains within himself the elements apt to move certain material or mental mechanisms which produce extraordinary phenomena.11David-Neel (1932/1971), 7.

For ethnographers like Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard, whose research was based on detailed ethnographic fieldwork with living peoples, the intellectual evolutionist schemes of nineteenth century anthropologists were untenable in the light of ethnographic facts. Magic and witchcraft could not simply be thought of as evolutionarily redundant phenomena because they continue to play an important role even within contemporary, highly developed, cultures. In Evans-Pritchard’s words: ‘belief in witchcraft is not incompatible with a rational appreciation of nature’. The work of Alexandra David-Neel, although by no means as influential in academic circles as Malinowski and Evans-Pritchard’s, was arguably also a significant contribution to the anthropology of the paranormal, emphasizing the importance of immersive participation in the culture under study. Magical beliefs and practices could no longer be thought of as ‘primitive’ or ‘irrational,’ but instead be seen to perform deeply embedded social and psychological functions, with practical importance for the social group. There remained the intriguing possibility that magical beliefs and practices might refer to genuine anomalous phenomena, as Andrew Lang had suggested decades earlier.

The 1950s and 1960s

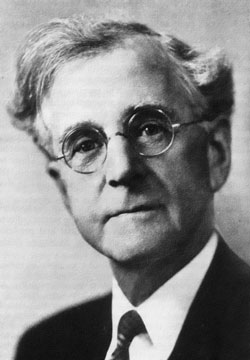

John Reed Swanton’s 1953 ‘Letter to Anthropologists,’ first published in the Journal of Parapsychology, represents a major step in the progression of this line of inquiry. It opens with the declaration that ‘a significant revolution which concerns us all [anthropologists] is taking place in a related branch of science’. Swanton meant the field of parapsychology, and in particular in the work of JB Rhine’s Parapsychology Laboratory at Duke University. For Swanton, a well respected member of the anthropological establishment, it was the evidence for telepathy, provided through simple line drawing experiments, that prompted his deeper reading into the literature of parapsychology and psychical research. He was also impressed by the research of psychologist William James and colleagues into the abilities of the American medium Leonora Piper, whom James had called his ‘white crow’. Swanton’s letter calls for anthropologists to take the long neglected data of psychical research seriously, and to consider what implications the evidence for psi phenomena might have for the anthropological enterprise.12Swanton (1953), 144-52.

Seven years later, Clarence W Weiant took up Swanton’s challenge with a paper published in the journal Manas, in which he outlined three aims: (1) to summarize the development of parapsychology, (2) to take note of the influence of parapsychology upon anthropologists, and (3) to point out the desirability of cooperation between parapsychologists and anthropologists.13Weiant (1960), 1.

Weiant argued that, for the most part, anthropologists had been fairly reserved in their discussions of paranormal phenomena encountered in the field, generally seeking to ignore or explain them away in terms alien to the interpretations of their host cultures. He did note some exceptions in the history of anthropology, however, among them the biologist Alfred Russel Wallace’s endorsement of Sir William Barrett’s research on dowsing as anthropologically valid; Andrew Lang’s pioneering work on the origins of religion; and the investigations by Ronald Rose into the psychic abilities of Australian Aborigines.

Weiant concludes his paper with the suggestion that ‘every anthropologist, whether believer or unbeliever, should acquaint himself with the techniques of parapsychological research and make use of these … to establish what is real and what is illusion in the so-called paranormal’ (a theoretical position quite different to Evans-Pritchard’s, above). Weiant writes:

If it should turn out that the believers are right, there will certainly be exciting implications for anthropology. We shall have to re-think Lang’s theory of the origin of religion and magic. Students of culture and personality will find their field enormously expanded […] The Physical anthropologists […] will have a multitude of new problems. Are there racial differences in ESP ability? Is there a genetic factor? Is it in any manner dependent upon neural organisation? Can it be cultivated?14Weiant (1960), 5.

Francis Huxley’s short 1967 chapter entitled ‘Anthropology and ESP’ highlights the tendency of anthropological accounts of witchcraft, magic, divination and shamanism to ignore the possibility that ESP might be a genuine phenomenon. He further suggests that there is a ‘general anthropological conclusion that tribal diviners (for instance) use quite ordinary methods to achieve their ends’. Huxley then points out that despite the apparent rarity of instances of ESP amongst his Haitian informants, they nevertheless held a strong belief in the existence of such a faculty, he writes: ‘Wherever one finds divination practised, one finds a belief in ESP’. Huxley then observes how a cross-cultural survey of divinatory techniques reveals a fundamental core characteristic: ‘a profound dissociation has to be provoked, during which the normal connections between consciousness and physical activity are severed’. In other words Huxley recognises the crucial role of altered states of consciousness in the mediation of ESP experiences. He suggests that ethnographic observation of practices such as shamanism and spirit mediumship may reveal ‘a basic process which often seems to bring ESP in its train,’ and argues that such a process would be ‘at once psychological and social’. We begin to see here the emergence of a processual approach to the study of the paranormal, examining the psycho-social processes conducive to ESP experiences.15Huxley (1967).

Published in 1968, Carlos Castaneda’s bestselling book The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge represented something of a benchmark (albeit a particularly controversial one) in the history of anthropology’s involvement with the paranormal. In the book Castaneda describes his experiences as an apprentice of Don Juan Matus, a traditional Yaqui sorcerer in Arizona. Don Juan teaches Castaneda about the ritual consumption of various psychoactive plants, including Datura and Peyote, and about how to use them for sorcery. Castaneda’s book is filled with vivid descriptions of encounters with supernatural beings in altered states of consciousness:

At the foot of one boulder I saw a man sitting on the ground, his face turned almost in profile. I approached him until I was perhaps ten feet away; then he turned his head and looked at me. I stopped –his eyes were the water I had just seen! They had the same enormous volume, the sparkling of gold and black. His head was pointed like a strawberry; his skin was green, dotted with innumerable warts. Except for the pointed shape, his head was exactly like the surface of the peyote plant. I couldn’t take my eyes away from him. I felt he was deliberately pressing on my chest with the weight of his eyes. I was choking. I lost my balance and fell to the ground. His eyes turned away. I heard him talking to me. At first his voice was like the soft rustle of a light breeze. Then I heard it as music – a melody of voices – and I ‘knew’ it was saying, ‘What do you want?’.16Castaneda (1968/1976), 99-100.

For Castaneda these experiences were indicative of a ‘Separate Reality’, and his descriptions were presented as a factual ethnographic account of his apprenticeship to Don Juan. There is debate as to whether this was actually the case, with some researchers claiming to have uncovered inaccuracies in Castaneda’s ethnography, along with evidence that certain of his claimed hallucinatory descriptions matched accounts found in the UCLA library.17See, for instance, De Mille (1976/2000). Despite major issues over authenticity, Castaneda’s book undoubtedly had a significant effect on popular attitudes towards traditional systems of belief, and inspired many to learn about shamanic and other consciousness altering techniques: see Schrol (2005).

In 1968, a posthumously published book by Italian philosopher and anthropologist Ernesto de Martino (1908–1965), entitled Magic: Primitive and Modern, presented a synthesis of the findings of anthropology and parapsychology. One of his most significant observations was that the laboratory investigation of psi involves a reduction of the emotional and environmental contexts within which psi experiences naturally occur. He wrote that ‘in the laboratory, the drama of the dying man who appears … to a relative or friend, is reduced to an oft-repeated experiment – one that tries to transmit to the mind of a subject the image of a playing card, chosen at random’. This, he suggests, represents ‘an almost complete reduction of the historical stimulus that is at work in the purely spontaneous occurrence of such phenomena’. In other words; the drama of real life is ignored in the laboratory experiment, much to the detriment of our understanding of psi. It is precisely at this juncture that the ethnographic methodology succeeds in illuminating the nature of the paranormal, so de Martino argues, through documenting its occurrence in the midst of the social drama that allows it to manifest in its most elaborate forms. De Martino’s contribution is important, and often overlooked in surveys of anthropology and parapsychology.18de Martino (1968/1972).

Margaret Mead is regarded as one of the twentieth century’s most influential anthropologists: her interest in parapsychology is less well known. Mead took part in parapsychological laboratory experiments with psychologist Gardner Murphy, using Zener cards, and was interested in understanding the social and psychological dynamics of psychic sensitives.19Schwartz (2000), 5. In 1969 Mead’s reputation as a highly respected member of the intellectual community, and her openness towards psychical research, were influential in the incorporation of the Parapsychological Association into the American Academy of Sciences, thus crystallising (if controversially) parapsychology’s status as a valid area of scientific inquiry.

The 1970s and 1980s: Transpersonalism Emerges

1973 saw the first international conference specifically concerned to explore the connections between anthropology and parapsychology. This was organized by the Parapsychology Foundation and held in London; its proceedings were published in 1974.20Angoff & Barth (1974). The conference was attended by, among others, social anthropologist IM Lewis, known for his functionalist social-protest theory of spirit possession practices, and biologist Alister Hardy, founder of the Religious Experience Research Unit at Manchester College, Oxford. Diverse topics covered over the course of the conference included: ‘The Implications of ESP Experiments for Anthropological ESP Research,’ The Anthropologists’ Encounter With the Supernatural,’ ‘Anthropology, Parapsychology and Religion,’ and ‘An Investigation of Psi Abilities Among the Cuna Indians of Panama,’ among others.

The book Extrasensory Ecology: Anthropology and Parapsychology,21Long (1977). edited by Joseph K Long, was also a particularly important development. Featuring contributions on wide ranging topics, from overviews of parapsychology and anthropology, ‘The Physical Bases for Paranormal Events,’ ‘The Origins of Psi,’ ‘Paranormal Dimensions in Primitive Medicine’ and more. Long’s professional curiosity about the paranormal largely derived from his own highly unusual experiences while conducting fieldwork in Jamaica.22Schwartz (2000).

These two publications were groundbreaking in their presentation of a seriously reasoned anthropological evaluation of the evidence from parapsychology, and the implications of this data for theory development in anthropology, and were the seeds for what would eventually emerge as transpersonal anthropology and the anthropology of consciousness. Indeed, Joseph Long went on to serve as president for the Association for Transpersonal Anthropology (1980–81) and the Association for the Anthropological Study of Consciousness (1984–86), and was the first editor of the journal Anthropology of Consciousness.23Winkelman (1999).

Robert Van de Castle, in a 1976 chapter entitled ‘Some Possible Anthropological Contributions to the Study of Parapsychology,’ suggests that ethnographic fieldwork might provide for parapsychology what Darwin’s Galapagos Island expedition gave to biology. In other words, an anthropological approach to parapsychology might enable researchers to ‘observe at first hand how psi products can be shaped by environmental and cultural influence’. Van de Castle criticizes the tendency of parapsychologists to seek demonstrations of psi in the laboratory at the expense of studying spontaneous psi experiences. He also attacks what he considers the prejudice shown by anthropologists who dismiss non-Western magical beliefs and practices as irrational, primitive and fraudulent, critiquing traditional social functional interpretations of systems of magical belief and practice for ignoring the experiences of ethnographic informants. Van de Castle goes on to caution parapsychologists of the need to be culturally sensitive in the development of experimental protocols for testing psi in the field. The paper concludes with an examination of the correspondence between claims to paranormal cognition (clairvoyance, precognition, telepathy, and so on), and the ingestion of psychoactive drugs, thus further highlighting the cross-cultural centrality of altered states of consciousness in the manifestation and experience of psi phenomena.24Van de Castle (1976), 151-61.

Although not directly concerned with parapsychology, the work of French anthropologist Jeanne Favret-Saada also has relevance to the anthropology of the paranormal. In the 1970s Favret-Saada conducted fieldwork in an area of rural France known as the Bocage, published in 1977 as a monograph under the title Deadly Words. Favret-Saada found a strong current of belief in witchcraft in the region, persisting even in the latter half of the twentieth century. The witchcraft beliefs of the rural communities she investigated, similar to those of the Azande, were intimately entwined with notions of misfortune, especially in the case of an unlikely string of unfortunate events. A single occurrence such as the death of some livestock would not necessarily be seen to be caused by witchcraft, but if this event occurred coincidentally alongside other misfortunes, such as family illnesses, a car crash, and a bad crop yield, then a deliberate act of witchcraft might seem more likely (again we see witchcraft as a connecting principle). Once an individual suspects that they are the victim of witchcraft, they will seek out the assistance of an ‘unwitcher’, a professional magical practitioner, to perform specific rites to counter the malicious attacks of the supposed witch, who may be a jealous neighbour or other member of the local community. Over the course of her research Favret-Saada was herself identified as an unwitcher. Like Evans-Pritchard’s study of Azande witchcraft, Favret-Saada’s investigations revealed the social-functional aspect of witchcraft beliefs (serving to express and diffuse social tensions), and offered insight into the participatory nature of witchcraft beliefs and magic more generally: it becomes real and efficacious by means of participation and immersion.25Favret-Saada (1977/2010).

Between 1976 and 1984, anthropologist Paul Stoller became a sorcerer’s apprentice amongst the Songhay people in the Republic of Niger. Under the tutelage of the sorko benya (sorcerer) Adamu Jenitongo, Stoller ‘memorized magical incantations, ate the special foods of initiation, and participated indirectly in an attack of sorcery that resulted in the temporary facial paralysis of the sister of the intended victim’. The deeper Stoller immersed himself in the world of Songhay sorcery, the more he began to fear the magical attacks of rival sorcerers, until, in 1979, he was forced to return home, fearful for his life, after a terrifying attack by a powerful sorcerer:

Suddenly I had the strong impression that something had entered the house. I felt its presence and I was frightened. Set to abandon the house to whatever hovered in the darkness, I started to roll off my mat. But my lower body did not budge … My heart raced. I couldn’t flee. What could I do to save myself? Like a sorko benya, I began to recite the genji how, for Adamu Jenitongo had told me that if I ever felt danger I should recite this incantation until I had conquered my fear … I began to feel a slight tingling in my hips … The presence had left the room.26Stoller & Olkes (1989), 148.

Stoller’s encounter with sorcery revealed the powerful nature of magical beliefs and practices as lived experience. He was exposed, first hand, to the dual nature of magic, sorcery and witchcraft, as simultaneously fascinating and terrifying (recalling Rudolph Otto’s dissection of the numinous experience into the mysterium fascinans and mysterium tremedum).27Otto (1958). Stoller’s experience led him to question the responsibility of the ethnographer working in the field, forcing him to ask whether it was really ethical for an anthropologist to learn the techniques of the sorcerer, or to participate in magical attacks in the course of ethnographic fieldwork? In spite of anthropology’s generally negative attitude towards the efficacy of magic, it may nevertheless have important social and psychological power within the host culture that should not be taken lightly. His experiences also brought into question the fundamentals of the ethnographic method of participant observation, and in particular the extent to which an ethnographer engaged in such practices can maintain a sense of objective detachment from their research subjects.

Writing in 1978, Richard de Mille, who had been one of Castaneda’s chief critics, emphasized the importance of carrying out ‘anomalistic anthropology’, in which anthropologists clarify their own tacit assumptions about the paranormal when presenting ethnographic descriptions of anomalous experiences. He writes:

[T]he anthropologist’s assumptions about the paranormal should be made explicit at all stages of work, whether planning, observing, analyzing, or reporting. Every anthropologist makes assumptions about the paranormal. Most of these are tacit assumptions. When apparent anomalies are unexpectedly encountered, hidden assumptions bring about skeptical or subscriptive reactions that may not represent the best interpretations the anthropologist is capable of. Either following such an unexpected encounter or before intentional observation, the anthropologist should interrogate himself (includes herself) about all beliefs, feelings, and predispositions toward manifest or alleged paranormal events and make his findings about himself explicit in writing.28De Mille (1979), 70.

Here de Mille is promoting a shift towards a more reflexive anthropological method, one that does not attempt to remove the ethnographic observer from his/her account. This particularly important in anomalous experiences described in ethnographic writing, and may reveal significant contributing processes. Indeed, it may have direct relevance to parapsychological experimentation, which similarly seems to be affected by the involvement of the experimenter in the experiment. Again, the clear distinction between the observer and the observed appears to break down.

The importance of understanding the role of the observer as participant is evident in other ethnographic accounts of the anomalous also. In 1983, for example, anthropologist Bruce Grindal published a vivid ethnographic description of the apparent re-animation of a corpse during a traditional Sisala death divination in Ghana, witnessed and documented in the 1960s:

What I saw in those moments was outside the realm of normal perception. From both the corpse and goka came flashes of light so fleeting that I cannot say exactly where they originated […] A terrible and beautiful sight burst upon me. Stretching from the amazingly delicate fingers and mouths of the goka, strands of fibrous light played upon the head, fingers, and toes of the dead man. The corpse, shaken by spasms, then rose to its feet, spinning and dancing in a frenzy.29Grindal (1983), 68-69.

What is so unique about Grindal’s account is that his anomalous experience is described as one moment in an ongoing ethnographic context, detailing not only the social and cultural climate within which it occurred, but also his own psychological and emotional states leading up to the event. Following the ominously close deaths of two members of the same village, it was deduced that the resultant funeral would be a ‘hot’ event ‘involving ritual danger, or bomo’. Grindal’s account of the incident included the days leading up to the funeral, during which the anthropologist’s daily routine was significantly disrupted, so that by the time it took place, with the ‘death divination’ that necessarily accompanied it, he was physically and mentally exhausted. All of these conditions converged to produce, mediate, or facilitate Grindal’s paranormal experience, and serve as an illustrative example of what Ernesto de Martino called the ‘drama’ of the real life context of the paranormal.

Michael Winkelman’s 1982 paper ‘Magic: A Theoretical Reassessment’ challenged dominant anthropological theories of magic as purely social and psychological phenomena by suggesting that the use of psi might be inherent in systems of magic, shamanism, witchcraft, divination and healing. Winkelman notes key correspondences between traditional forms of magic and the research findings of parapsychology, including the central significance of:

- Altered states of consciousness

- Visualisation techniques

- Positive expectation

- Belief

Besides being fundamental to traditional magico-religious practices, these factors have been found to help facilitate psi functioning in the laboratory setting. Winkelman goes on to draw parallels between key concepts in anthropological theories of magic and specific forms of psi. For example, the anthropological notion of mana, a term used to denote supernatural power, is associated with psi in general. Magic, understood as the ability to affect change in the physical world, is associated with psychokinesis, and divination is associated with psi-mediated information gathering, for example through clairvoyance, telepathy and precognition. Experimental evidence exists for all of these phenomena, albeit usually on quite a small (though statistically significant) scale, reinforcing the suggestion that traditional forms of magic might utilize psi.30Winkelman (1982).

Patric Giesler’s 1984 paper ‘Parapsychological Anthropology: Multi-Method Approaches to the Study of Psi in the Field Setting,’ published in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, seeks to improve the one-sided approaches of both parapsychology and anthropology ‘by suggesting refinements in each and by proposing combinational and integrated … approaches to the study of psi processes in their psychosocial contexts’. Giesler sees useful potential for applying insights into the nature of psi derived from parapsychology to help interpret the anthropology of magic and religion. Conversely, he argues that parapsychology has failed to ‘take advantage of the exceedingly rich insights provided by ethnographic fieldwork and cross-cultural research.’.

The paper calls for a process-oriented approach to psi, one that takes into account the many ecological variables (ethnographic facts), that correlate with the occurrence of psi phenomena. He argues that insights into the psychosocial contexts within which psi phenomena naturally occur can be synthesized into new models for laboratory testing of psi.The close association between the cultural use of altered states of consciousness and a ‘deeply instilled belief in the existence of psychical phenomena,’ is once again reiterated. Giesler’s approach marks a significant step away from the traditional bracketing out of questions of ontology in phenomenological and social-scientific approaches to supernatural beliefs, proposing instead that experiments be carried out to test their reality. He writes that:

[O]ne of the purposes of anthropology is to explain the ontology, development, and function of the beliefs, practices, and claims of magico-religious experiencers … it should assume that psi could exist and then proceed etically on that assumption.31Giesler (1984), 302-3.

Charles D Laughlin defines transpersonalism as ‘a movement in science toward seeing the significance of experiences had in life, that somehow go beyond the boundaries of ordinary ego-consciousness, as data’. Such experiences might include ‘unitive consciousness, meta-needs, peak experiences, ecstasy, mystical experience, being, essence, bliss, awe, wonder, transcendence of spirit’ and so on. Laughlin places a central significance on a first-person phenomenological approach to the study of transpersonal states of consciousness. In particular he employs Charles Tart’s notion of ‘state-specific science’ to emphasize the importance of immersive participation and the need to achieve firsthand experience of culturally significant transpersonal states. He writes:

‘One must be willing steep oneself in the symbolism, to live it to the full’ and in so doing one may have the opportunity to directly experience the kind of powerful adventure that enlivens the natives’ view of themselves and their cosmos’.32Laughlin (2012), 96.

The 1990s and 2000s: Return to Experience and Ontology

Edith Turner33Turner (1993), 9-12; (1998). has called for an approach to the study of traditional ritual that takes seriously the beliefs and experiences of informants when conducting ethnographic fieldwork. Following her own unusual experiences during the ihamba healing ceremony of the Ndembu in Zambia, Turner concluded that in order to truly understand and appreciate a particular belief system the anthropologist must learn to ‘see what the native sees,’ through a process of active and emotional participation in their belief system and rituals. She sums up the essentials of this position eloquently, laying out guidelines for anthropologists to follow:

[That] we endorse the experiences of spirits as veracious aspects of the life-world of the peoples with whom we work; that we faithfully attend to our own experiences in order to judge their veracity; that we are not reducing the phenomena of spirits of other extraordinary beings to something more abstract and distant in meaning; and that we accept the fact that spirits are ontologically real for those whom we study.34 Turner (2010), 224.

David E Young and Jean-Guy Goulet’s Being Changed by Cross-Cultural Encounters was also important in bringing about a new anthropological approach to the paranormal, notably by taking seriously the extraordinary experiences of ethnographers engaged in fieldwork. In their introduction the authors describe their threefold aims:

(1) to provide personal accounts by anthropologists who have taken their informants’ extraordinary experiences seriously or who have had extraordinary experiences themselves;

(2) to develop the beginnings of a theoretical framework that will help facilitate an understanding of such experiences;

(3) and to explore how such experiences can be conveyed and explained to a ‘scientifically-oriented’ audience, in such a way that they are not automatically dismissed without a fair hearing.35Young & Goulet (1994), 12.

Drawing inspiration from Turner’s writings, Frank Salamone has highlighted the need for a return to holism in anthropology. He writes that this holistic approach must go beyond ‘a simple return to the holism of anthropology’s earlier days of somewhat distanced reporting of the Other’, adding that the aim is to seek ‘an experiential union with the Other and not only a respect for the spirituality of the Other but also an acceptance of it’.36Salamone (2002), 155. These themes have subsequently been further developed by others, as we shall see.

In 2002, sociologists James McClenon and Jennifer Nooney showed just how common anomalous experiences are in the ethnographic literature when they published a short article detailing forty separate anomalous experiences reported by sixteen anthropologists in the field. Comparing the experiences of anthropologists with 1446 anomalous experiences collected from undergraduate students between 1988 and 1996, the authors note distinct similarities in experience and suggest, in line with David J Hufford’s work, that the ‘experiential source’ hypothesis has greater explanatory power than the standard ‘cultural source’ hypothesis. McClenon and Nooney go on to suggest that scholarly engagement with anomalous experiences can provide novel insights into anthropological theories of religion:

Field anthropologists, as ‘professional observers,’ have a unique position within the social sciences. They undergo special training designed to increase their ability to transcribe their experiences accurately. As a result, their reports have special rhetorical power compared to those of lay people. Published accounts of their anomalous experiences constitute a particularly ‘worthy’ body of data, especially valid for testing social scientific hypotheses pertaining to the origin of religion.37McClenon & Nooney (2002), 49.

An example of how the ethnographer’s encounter with such experiences can shed light on the origins of wider belief systems can be found in the work of ethnographer Zeljko Jokic. Writing on his experiences with the Yanomami of the Orinoco Valley, Jokic describes how his own subjective experiences under the influence of the hallucinogenic snuff Yopo represented a point of intersubjective entry into the Yanomamo life-world. Through his encounters with the reality revealed in the psychedelic state, Jokic gained an appreciation of the experiential underpinnings of Yanomami cosmology, a deeper understanding that could not have been gained in any other way – an experiential understanding.38Jokic (2008).

As if to take us a little deeper down the rabbit hole, Joan Koss-Chioino suggests that in discussions of the supernatural belief systems of ethnographic informants the question of ‘spirit reality cannot be dismissed,’ especially because ‘reports of experiences of spirits are ubiquitous in the world, in all cultures’.39Koss-Chioino (2010),134.. Anthropologists ought, therefore, to take seriously the supernatural beliefs and experiences of their ethnographic informants because they represent foundational suspects of many of the world’s cultures.

Fiona Bowie proposes a methodology, which she terms ‘cognitive empathetic engagement’,’as a means to achieve this goal. Cognitive empathetic engagement is defined as a method by which ‘the observer … approaches the people or topic studied in an open-minded and curious manner, without presuppositions, prepared to entertain the world view and rationale presented and to experience, as far as possible and practical, a different way of thinking and interpreting events’.40Bowie (2010), 5. The ultimate aim of this type of approach is to interpret religious and spiritual beliefs from a perspective that does not, from the very outset, reduce the complexity of the phenomenon or ignore the significance of personal, subjective experience.

Susan Greenwood has proposed a means to overcome the conceptual difficulties associated with the academic study of the paranormal, advocating an approach centered around the notion of ‘magical consciousness’. Magical consciousness is ‘characterized by the notion of participation, an orientation to the world based on persons and things in contact with a non-ordinary spirit reality?’ She explains how ‘it is possible to overcome the anthropological dilemma of the reality of spirits by adopting an attitude of spiritual agnosticism by not believing or disbelieving in their reality’.41Greenwood (2013). This approach is essentially phenomenological, employing a form of ontological bracketing, but not of dismissing paranormal claims and experiences.

In a recent article Aaron Joshua Howard examines the ontological assumptions of four contemporary anthropologists (Emma Cohen, Katherine P. Ewing, Edith Turner and Mary Keller) as they relate to the supernatural beliefs and experiences of their fieldwork informants. The article focuses on anthropology’s attempt to overcome the hegemonic bias of much discussion of religion, in particular of non-European religion. Howard classifies the approaches of these ethnographers in different ways:

Emma Cohen’s cognitive explanation for spirit possession practices is classed as a form of exclusive naturalism, whereby the beliefs and experiences of her informants are held to be little more than misinterpretations of otherwise normal cognitive processes; her analysis leaves no room for the native perspective that spirit possession involves genuine interactions with a supernatural reality.

Katherine P Ewing’s research with Pakistani Sufi Muslims, by contrast, is referred to as assimilation, whereby common ground is sought between the native interpretation and the ethnographer’s own cultural interpretation, for example by seeking commonalities between Sufi dream theory and Freudian dream theory.

Edith Turner’s approach is labelled supernatural absorption, and involves the construction of a ‘theologically discursive space where the unexpected can happen, with the unexpected being indicative of a certain reality, and not merely figments of imagination or hocus-pocus’.

The fourth approach discussed by Howard, embodied in Mary Keller’s work on spirit possession, is referred to as theological realism, which ‘understands that supernatural entities exist’ but does not assume that she can intimately know them.

To conclude his overview, Howard suggests that:

Ethnographic methods and anthropological research will continue to be oppressive unless the scholar can take seriously that something, whatever it is, happens within the rituals that tap into gods, spirits, ancestors, that is outside of Freud, Durkheim, or Tylor’s ability to explain. Unless anthropologists are willing to open a discursive space that allows for the transcendent and the supernatural, their research will continue to oppress and demean societies from which we have much to learn.42Howard (2013).

Howard is here suggesting that for anthropologists to truly understand the ‘native’s’ point of view, especially with regard to matters of the supernatural or paranormal, they must retain an openness to the possibility that standard psychological and sociological models might not be able to account for everything we encounter in the field. It could be, for example, that there is more to supernatural belief systems than purely sociological or psychological functionalist frameworks allow for – there might even be a kernel of truth underlying them. It is only through opening up to such possibilities that the ethnographer can even begin to appreciate the relevance of supernatural beliefs to everyday lived experience. Ethnographic informants do not understand the objects of their beliefs in terms of psychological or social functioning, but rather as living components of real life. It is this kind of ontological openness, Howard argues, that should provide the springboard from which future ethnographic studied of the paranormal should begin. It is also the discursive avenue that might lead to future collaborations between anthropologists and parapsychologists, both in the field and in the laboratory.43See, for example, Storm & Rock (2009).

Jack Hunter

Literature

Angoff, A., & Barth, D. (1974). Parapsychology and Anthropology: Proceedings of an International Conference held in London, England, August 29-31, 1973. New York: Parapsychology Foundation.

Castaneda, C. (1968/1976]). The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

David-Neel, A. (1932/1971]). Magic and Mystery in Tibet. London: Corgi Books.

de Martino, E. (1968/1972]). Magic: Primitive and Modern. London: Tom Stacey.

De Mille, R. (1976/2000]). Casteneda’s Journey: The Power and the Allegory. Bloomington, Indiana, USA: iUniverse.

De Mille, R. (1979). Explicating anomalistic anthropology with help from Castaneda. Zetetic Scholar, No. 3-4, 69-70.

Devereux, P. (2007). The moveable feast. In Mind Before Matter: Visions of a New Science of Consciousness, ed. by T. Pfeiffer, J.E. Mack, & P. Devereux, 178-91. Winchester, UK: O Books.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. (1937/1976). Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. (1965/1972). Theories of Primitive Religion. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Favret-Saada, J. (1977/2010). Deadly Words: Witchcraft in the Bocage. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Frazer, J.G. (1890 [1993). The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Hertfordshire, UK: Wordsworth Editions.

Giesler, P.V. (1984). Parapsychological anthropology I: Multi-method approaches to the study of psi in the field setting. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 78/4, 289-339.

Grindal, B.T. (1983). Into the heart of Sisala experience: Witnessing death divination. Journal of Anthropological Research 39/1,60-80.

Greenwood, S. (2013). On becoming an owl: Magical consciousness. In Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West: Between Mind & Body, ed. by G. Samuel & J. Johnston, 211-18. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Guthrie, S. (1993). Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Howard, A.J. (2013). Beyond belief: Ethnography, the supernatural and hegemonic discourse. Practical Matters 6, 1-17.

Huxley, F. (1967). Anthropology and ESP. In Science and ESP, ed. by J.R. Smythies, 281-302. London: Routledge & Keagan Paul.

Jokic, Z. (2008). Yanomami shamanic initiation: The meaning of death and postmortem consciousness in transformation. Anthropology of Consciousness 19/1, 33-59.

Koss-Chioino, J. (2010). Introduction to ‘Do Spirits Exist? Ways to Know’. Anthropology and Humanism 35/2, 131-41.

Lang, A. (1985/2010]). Cock Lane and Common Sense. Charleston, South Carolina, USA: Bibliobazaar.

Laughlin, C. (2012). Transpersonal anthropology, then and now. In Paranthropology: Anthropological Approaches to the Paranormal, ed. by J. Hunter. Bristol, UK: Paranthropology.

Long, J.K. (1977). Extrasensory Ecology: Parapsychology and Anthropology. London: Scarecrow Press.

Luke, D. (2010). Anthropology and parapsychology: Still hostile sisters in science? Time and Mind: Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness and Cuture 3/2, 245-66.

Malinowski, B. (1948/1974]). Magic, Science and Religion. London: Condor Books.

McClenon, J., & Nooney, J. (2002). Anomalous experiences reported by field anthropologists: Evaluating theories regarding religion. Anthropology of Consciousness 13/1, 46-60.

Northcote, J. (2004). Objectivity and the supernormal: The limitations of bracketing approaches in providing neutral accounts of supernormal claims. Journal of Contemporary Religion 19/1, 85-98.

Otto, R. (1958). The Idea of the Holy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Salamone, F.A. (2002). The tangibility of the intangible: Beyond empiricism. Anthropology and Humanism 26/2, 150-57.

Schroll, M.A. , & Schwartz, S.A. (2005). Whither psi and anthropology? An incomplete history of SAC’s origins, its relationship with transpersonal psychology and the untold stories of Castaneda’s controversy. Anthropology of Consciousness 16/1, 6-24.

Schwartz, S.A. (2000). Boulders in the stream: The lineage and founding of the Society for the Anthropology of Consciousness. [Web page.]

Sera-Shriar, E. (2022). Psychic Investigators: Anthropology, Modern Spiritualism, and Credible Witnessing in the Late Victorian Age. University of Pittsburg Press.

Stocking, G.W. (1971). Animism in theory and practice: E.B. Tylor’s unpublished notes on “Spiritualism.” Man 6/1, 88-104.

Stoller, P., & Olkes, C. (1989). In Sorcery’s Shadow: A Memoir of Apprenticeship Among the Songhay of Niger. Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Storm, L., & Rock, A.J. (2009). Shamanic-like journeying and psi: I. Imagery cultivation, paranormal belief, and the picture-identification task. Australian Journal of Parapsychology 9/2, 165-92.

Swanton, J.R. (1953). A letter to anthropologists. Journal of Parapsychology 17, 144-52.

Turner, E. (1993). The reality of spirits: A tabooed or permitted field of study? Anthropology of Consciousness 4/1, 9-12.

Turner, E. (2010). Discussion: ethnography as a transformative experience. Anthropology and Humanism, 35/2, 218-26.

Tylor, E.B. (1871). Primitive Culture: Researches into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Language, Art and Custom (2 vols.). London: John Murray.

Van de Castle, R.L. (1976). Some possible anthropological contributions to the study of parapsychology. In Parapsychology: Its Relation to Physics, Biology, Psychology and Psychiatry, ed. by G. Schmeidler. Metuchen, New Jersey, USA: Scarecrow Press.

Weiant, C.W. (1960). Parapsychology and anthropology. Manas 13/15, 1-6.

Winkelman, M. (1982). Magic: A theoretical reassessment. Current Anthropology 23/1, 37-66.

Winkelman, M. (1999). Joseph K. Long: Obituary. Anthropology News 40/9, 33.

Young, D.E., & Goulet, J.G. (1994). Being Changed by Cross-Cultural Encounters: The Anthropology of Extraordinary Experience. Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Broadview Press.