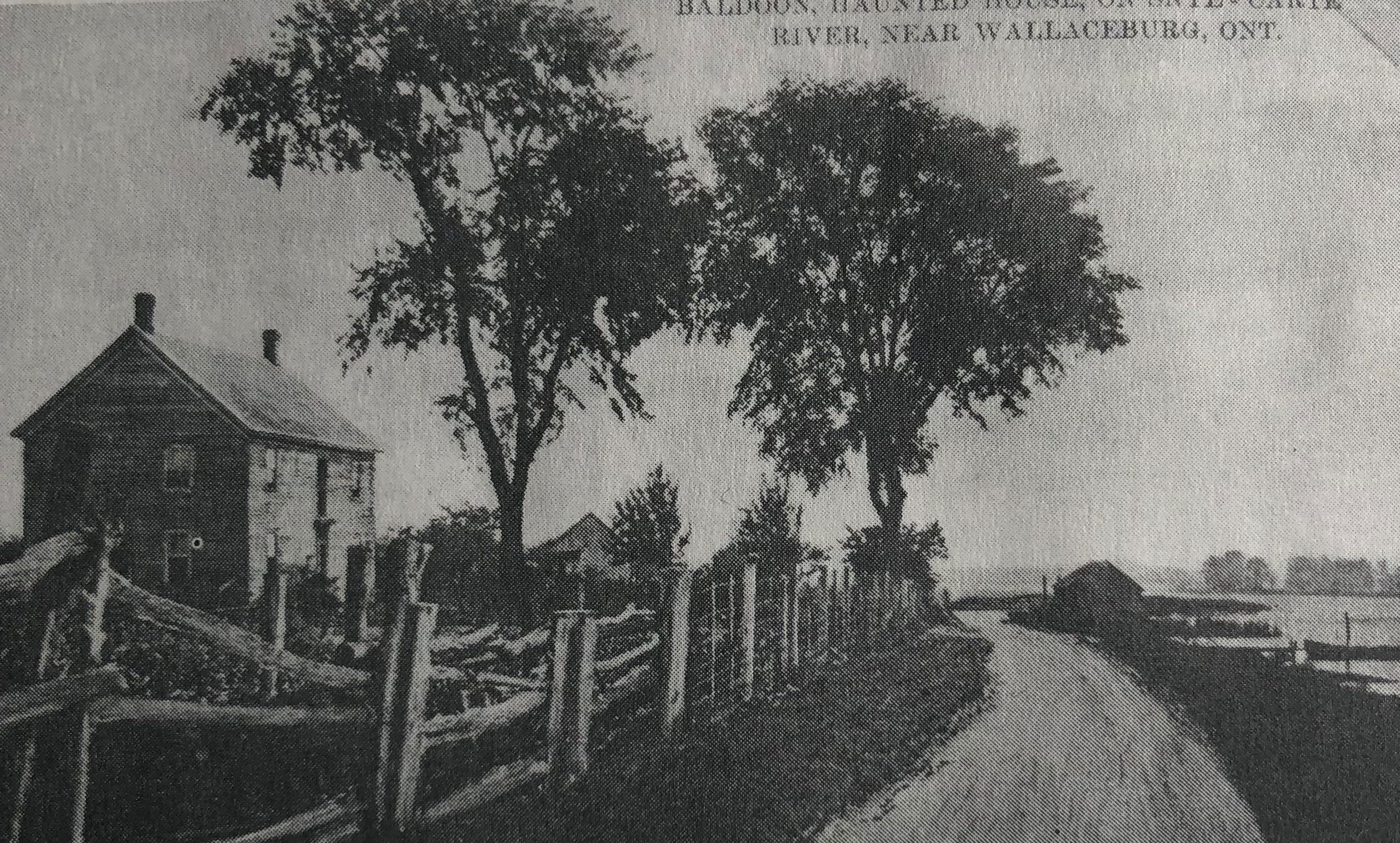

In November 1829, the settlement of Baldoon (near Wallaceburg, Ontario) was the site of what became Canada’s most widely reported poltergeist disturbance. The events, which occurred at the homestead of John McDonald, later became known as the Baldoon Mystery as a result of newspaper stories written by McDonald’s son, Neil T McDonald. The Colwell Printing Company printed the collected newspaper versions as a romanticized story titled The Baldoon Mystery in the early 1900s. Wallaceburg historian Alan Mann published an updated version in 1986. The book features 26 eyewitness accounts gathered by the younger McDonald some years after the events, along with historical notes and photographs related to the poltergeist.

The Incidents

The incidents described in The Baldoon Mystery are said to have begun shortly after John McDonald was approached by a local woman offering to purchase his property. The woman, whose identity is obscured, is described as belonging to the people of the ‘Long Low Log House’.1McDonald (1986/1991), 5. Her family is portrayed as anti-social, sullen, resentful, with few friends. The young McDonald steadfastly refused the woman’s offer, and this is said to have precipitated the unexplained events.

The men of the McDonald family were out farming and the women were weaving straw hats in the barn when a tall wooden pole fell, nearly striking the women. The women had barely regained their composure when other beams fell nearby one after another.

Soon after the incident in the barn, the family reported lead bullets breaking windows of the house and falling harmlessly to the floor. Word spread throughout the region, and several curious neighbours reported their own encounters on the McDonald farm. WL Burnham, who was sixteen years old at the time of the events, described pyrogeist activity: ‘… fire would start up in different places at the same time, and when this was extinguished, it would start in other places, and so on until January 1830, when the buildings were burned to the ground.’2McDonald (1986), 31.

An Indigenous hunter named Solomon Par-tar-sung recalled passing by the farm and attempting to put out the fires. ‘About thirty men were watching the house and putting out the fires about it. I was there when the house was burned. It had been set on fire about thirty times in less than three hours. A small coal about the size of a hickory nut would drop in any part of the house and a flame would kindle instantly … it would take fire on the wet floor the same as if it was oil.’3McDonald (1986/1991), 35.

The unexplained disturbances persisted after the family moved to the nearby home of Donald McDonald, the father of John. Most of the witness accounts were gathered decades after the incidents, and only one witness, WL Burnham, gave approximate dates for activity that happened prior to and following the family’s relocation. One witness, Margaret Johnson, said the McDonald family tried living in several houses, but unexplained and terrifying events followed them wherever they went.4McDonald (1986/1991), 46.

The most consistent witness recollection describes the phenomenon of lithobolia: twenty witnesses specifically noted lead balls – either lead shot from muskets or fishing nets – flying wildly about the property. Among the witnesses who reported lithobolia, twelve spoke of a rudimentary investigation to determine if the assailant was a person hiding among them. LA McDougald said, ‘I have been present when the balls came through the windows. I and others have picked them up, putting a private mark upon them and thrown them in the river, and in a short time the same balls so marked would come back through the window. At other times stones would come, wet, as if they were just out of the bed of the river.’5McDonald (1986/1991), 54.

A smaller number of witnesses reported unexplained auditory events, at times in the form of marching or stamping feet where nobody was walking. A smaller number of witnesses also reported visual spectacles. Victoria Hathaway, recalling her brother’s accounts, noted ‘he said that things would seem to come up through the floor and shape themselves into different forms, sometimes that of an Indian, sometimes that of a white man, but more often a large black dog.’6McDonald (1986/1991), 51. Other witnesses described the black dog apparition during catastrophic events. Darius Johnson spoke of the animal as having supernatural abilities, ‘He [McDonald] saw a large black dog sitting on the roof of a building, which was on fire, and they tried to knock it off, but it would bark and show its teeth as much as to say ‘mind your own business.’ It stood there until surrounded by fire, when it disappeared instantly.’7McDonald (1986/1991), 51.

Witnesses also described the McDonald’s pet dog and livestock as being a common target of aggression. Peter Appleton said, ‘I saw the mush pot chase the dog through a crowd of people, and the stick handle itself on the dog the same as a person would use it and the dog ran nearly wild.’8McDonald (1986/1991), 36.

The Black Goose

Several witnesses offered vague explanations for the poltergeist, for instance that an evil spirit was plaguing the McDonalds. Others were more specific, pointing to an older Indigenous woman as the cause of the events. According to several witnesses, the woman was a witch who could transform into a black goose, or a goose with one black wing. Some witnesses described McDonald seeking the guidance of a well-known witch doctor named Dr John Troyer, who lived near Long Point, Ontario.9Reaney (2003). Allen McDonald, a son of John McDonald, noted that Dr Troyer’s daughter uncovered the plot against his father: ‘She then told him that if that goose was there when he got home to put some silver in his gun and shoot it, and if he hit it, it would disappear and he could not tell how, but the next day to go to his family’s house, and he would find the old woman wounded by the silver he had shot her with the day before.’10McDonald (1986/1991), 40.

John McDonald did as he was instructed and shot the black goose in the wing. The following day, McDonald spotted an elderly woman walking down the road with her arm in a sling.

The Narrative

Although prefaced as a true story, Neil T McDonald’s narrative is conveyed as a colonial rite of passage in which the settlers subdue the malevolent spirits of the land. The implication extends to the local Indigenous population of the Anishinaabeg whose presence predated the settlers and whose grievances were directed towards settler encroachment. The eyewitness accounts to the events act as a plot device that moves the story along and ‘offers a dialectic that works through the failure of frontier settlement’.11Fehr et al. (2013), 260.

Analysis of the story has varied over time, from historical folkloric studies, psycho-analytical, to Indigenous Studies.12Laursen & Cropper (2014), 28-37. The published story offers a series of structuralist tropes through which a god-fearing and righteous settler man defeats the evil spirits of a wild and untamed land. At various points the family loses livestock, their home is burnt to the ground, and they cannot produce successful crops. The story loosely parallels the ordeals of the Baldoon settlement, which collapsed more than a decade prior to the events in the story.

As the story progresses, the antagonist is identified as the McDonald’s neighbour, an old woman with the ability to shapeshift into a black goose. As the protagonist unlocks the secrets behind the mysterious events plaguing his family, the antagonist is defeated and the family can live in peace.

Socio-cultural Context

There are two common theories related to the source of the poltergeist activity, and both are reflective of the McDonald’s presence on Indigenous land. Historian Alan Mann points to a confrontation between McDonald and another neighbouring Scottish family.13McDonald (1986/1991), 63. One source told Mann that the neighbour refused to sell a parcel of land to McDonald, while another source indicated the family heads clashed over common land between their properties. The land in question was the site of an Indigenous graveyard that was disturbed while the land was being cleared for farming.14McDonald (1986/1991), 63.

The tension over land is apparent throughout The Baldoon Mystery, and the implicit references to Indigenous peoples is derogatory. Re Re-Nah-Sewa noted the people responsible were known as the ‘wild Indians’15McDonald (1986/1991), 35. who lived on a prairie near where the McDonalds lived. None of the witnesses name the supposed assailants, but Neil T McDonald said ‘… they were not nice people, but were remarkable for a sullen, resentful air, and made few friends.’16McDonald (1986/1991), 5.

The social tensions between the settlers and the Anishinaabeg predated the events of 1829 by several decades. The McDonald family was among several settlers who moved north of the Baldoon settlement onto land known as the Chenail Ecarté tract.17Fehr et al. (2019). At least one of the families, the Stewarts, were accused of using duplicitous means to obtain property from the Anishinaabeg.18Fehr et al. (2019), 25. On other occasions, complaints were made by regional chiefs that the Baldoon settlement was being built without their permission and that its construction was preventing Indigenous farmers from sowing their seeds.19Library and Archives Canada (LAC) (1804).

Two other accounts by Indigenous witnesses offer more depth to the story. Chief Pashegeezhegwashkum, offered the earliest known commentary of the events at the McDonald home. He spoke with Reverend Peter Jones in the early 1830s and offered the following account, ‘O, I know all about it. The place on which the white man’s house now stands was the former residence of the Mamagwasewug, or fairies. Our forefathers used to see them on the bank of the river. When the white man came and pitched his wigwam on the spot where they lived, they removed back to a poplar grove, where they have been for several years. Last spring this white man went and cleared and burnt this grove, and the fairies have been obliged to remove; their patience and forbearance were now exhausted; they felt indiet algnant at such treatment, and were venting their vengeance at the white man for destroying their property.’20Jones (1861), 267-68.

The other account was offered by Chief Peterwegeschick in the early 1900s. The Elder chief noted the cause of the haunting to be the settlers’ destruction of a medicine lodge prior to building their farm.21Leonhardt (1925), 268.

Aftermath

The events at Baldoon gained notoriety in the following years and decades. Alan Mann noted the Baldoon house became a regular stop for passengers on a Detroit-based cruise ship. Mann noted, ‘the excursionists were a ready, waiting impressionable crowd’22McDonald (1986/1991), 64. whose attention was intently focused on the stories spun by the tour operators.

John McDonald became a well-known figure in the region. In the early 1840s his name appears on multiple lists of illegal squatters living on Walpole Island First Nation. As a non-Indigenous settler, McDonald had illegally occupied a portion of land on the island apparently in addition to his land holdings off the island. McDonald’s name appears alongside various other settlers, including other McDonalds who were identified for removal by the local Indian Agent. Among the two dozen or so settlers occupying Walpole Island, the agent went out of his way to name McDonald as a ‘very troublesome’ Scot.23Library and Archives Canada (LAC) (1843).

All of the witness accounts are clear that the events that comprise the Baldoon Mystery happened on the mainland in Sombra Township, formerly the Chenail Ecarté tract. Yet the presence of the McDonalds on Walpole Island and their subsequent removal provides greater dimension to the socio-cultural context to the settler meta-narrative.

Rick Fehr

Literature

Fehr, R. (2013). Settler narrative and Indigenous resistance in The Baldoon Mystery. In Empires of Nature and the Nature of Empires, ed. by Karl Hele. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Fehr, R., Macbeth, J., & Sands Macbeth, S. (2019). Chief of this river: Zhaawni-binesi and the Chenail Ecarté lands. Ontario History 111/1.

Jones (Kahkewaquonaby), Rev. Peter (1861). History of the Ojebway Indians; with especial reference to their conversion to Christianity. (London: A.W. Bennett).

Laursen, C., & Cropper, P. (2014). The Baldoon mystery. Fortean Times 315 (1 May), 28-37.

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) (1804). Daniel Claus Family Fonds, MG 19, F1, Vol. 9, C-1480: 25-27, Chief Wetawninsea to Col. Thomas McKee (24 May).

Library and Archives Canada (LAC) (1843). Indian Agent William Keating to Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs Samuel Jarvis, RG 10 Vol. 571: 6-7 (21 July).

Leonhardt, W. (1925). Legends of the St. Clair River. Sarnia Canadian-Observer (18 July).

McDonald, N.T. (1986/1991). The Baldoon Mystery, ed. by A. Mann. Standard Press.

Reaney J. (2003). ‘Troyer, John’. In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 7. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto/Université Laval.