Carlos Mirabelli (1889–1951) was a Brazilian medium credited with phenomena of similar power and frequency to those associated with DD Home, although he was little known in the English-speaking world.The occurrences were observed by credible witnesses in conditions sufficient to rule out fraud, and often in daylight.

Contents

Introduction

The case of the Brazilian medium, Carlos Mirabelli, is one of the most tantalizing and frustrating in psychical research. Psychical researcher Eric Dingwall considered the ocurrences he caused ‘so extraordinary indeed that there is nothing like them in the whole range of psychical literature’.1Dingwall (1930), 296. If all that was written about him was true, writes Guy Lyon Playfair, ‘he was without doubt the most spectacular physical effects medium in history’, adding:

You name it, and he is said to have done it; automatic writing in over thirty languages living or dead, speaking in numerous foreign tongues, materializing objects and people, transporting anything from a bunch of flowers to large pieces of furniture (including levitation of himself even when strapped to a chair), producing impressions of spirit hands in trays of flour or wax inside locked drawers, dematerializing anything in sight, himself included.2Playfair (2011), 23.

Mirabelli reportedly produced full-form materializations in bright daylight. Sitters would watch them form; attending physicians would carefully examine them for up to thirty minutes and report ordinary bodily functions; photographs of the figures would be taken; and then they would slowly dissolve or fade before everyone’s eyes.

Unfortunately, the case of Mirabelli never received the full scrutiny and documentation accorded Home, Palladino, and some others. In part, this may be due to the prevailing antipathy toward physical mediumship among prominent members of the SPR.3Inglis (1984), 221ff. Moreover, there is some evidence of fraud in Mirabelli’s case, most notably a doctored photograph (discussed later) of the medium apparently levitating.4Playfair, (1992, 2011).

Nevertheless, Mirabelli’s phenomena were witnessed by many, often under conditions apparently sufficient to rule out fraud, and they were frequently described in great detail. But most of those accounts were written in Portuguese, and for that reason they may have been either ignored or unfairly discounted by Anglo-American researchers.

Beginnings

Mirabelli was born to Italian parents in 1889, and Playfair writes that ‘like many sons of immigrants he never quite mastered either his ancestors’ or his adopted country’s language. He learned some English and possibly also some German, but certainly became no skilled linguist.’5Playfair (2011), 25.

Mirabelli’s history with psychokinesis seems to have begun in his early twenties, with some poltergeist-like outbreaks while he was employed at a shoe store. Legend has it that shoe boxes would fly off the shelves and sometimes follow the fleeing Mirabelli into the street. As a result, many concluded that Mirabelli was insane, and before long he was committed to an asylum. However, the psychiatrists in charge apparently had other ideas, and rather than putting Mirabelli into a straitjacket, they ran some tests and found that he could move objects at a distance. Their conclusion was that although Mirabelli was not normal, he was not insane. In their opinion, the phenomena occurring in Mirabelli’s vicinity were ‘the result of the radiation of nervous forces that we all have, but that Mr Mirabelli has in extraordinary excess’. So after a stay of only 19 days, Mirabelli was released.

Mediumship

Mirabelli’s mediumistic career began at this point and very quickly flourished. In response to a rapidly proliferating array of astounding reports, local newspapers began taking sides in the case, some (not surprisingly) accusing Mirabelli of outright fraud and others taking a more sympathetic view. But of course accusations of fraud come with the territory, and Mirabelli had many credible supporters. Indeed, as Dingwall observed, Mirabelli’s ‘friends and supporters included many from the best strata of S. Paulo society. Engineers, chemists, mathematicians, medical men, politicians, members of the various Faculties of Universities—all testified in his favour and recounted the marvels that they had witnessed in his presence’.6Dingwall (1930), 297.

Because Mirabelli’s feats were so astonishing, eventually a 20-person committee was established to adjudicate the case. The committee concluded that a more formal investigation should be conducted by people well-qualified to determine the authenticity of Mirabelli’s phenomena. That investigation was carried out by the Cesar Lombroso Academy of Psychical Studies, founded in 1919 for this purpose. Its report was published in 1926, and brought Mirabelli to the attention of researchers in the northern hemisphere.

Dingwall emphasized one very important feature of Mirabelli’s manifestations, which he cautioned might well be ‘forgotten by those who try to belittle the claims of Mirabelli’,7Dingwall (1930), 298. and which in fact were apparently forgotten later by Theodore Besterman, a SPR investigator (see below).8Besterman (1935). That important feature is that ‘the greater part of the phenomena observed with Mirabelli were investigated in broad daylight, even the materializations, telekinesis and levitations. When evening sittings were held these were undertaken in a room illuminated by powerful electric light’.9Dingwall (1930), 298, emphasis in original.

The phenomena observed during the Academy’s investigation divide into three categories:

- automatic writing in 28 different languages including 3 dead languages (Latin, Chaldaic and Hieroglyphic)

- spoken mediumship in 26 languages, including seven dialects

- physical phenomena including ‘levitation and invisible transportation of objects: the dematerialization of organic and inorganic bodies: luminous appearances and a variety of rapping and other sounds: touches: digital and other impressions upon soft substances, and finally the materialization of complete human beings with perfect anatomical features’.10Dingwall (1930).

Mirabelli’s linguistic productions, on ‘a wide range of subjects from medicine, law, sociology, to astronomy, musical science and literature’,11Dingwall (1930), 304. are remarkable because, as Playfair noted, ‘All witnesses I have interviewed agree without hesitation that Mirabelli could not even speak either of his own languages (Italian and Portuguese) correctly.’12Playfair (2011), 32-33.

The automatic writing was also remarkable for its diversity, quantity, and speed. As Dingwall noted,

we find [mediumistic control] Johann Huss impressing Mirabelli to write a treatise of 9 pages on ‘the independence of Chechoslovakia’ in 20 minutes; Flammarion inspiring him to write about the inhabited planets, 14 pages in 19 minutes, in French; Muri Ka Ksi leading him to treat the Russian-Japanese war in Japanese, in 12 minutes to the extent of 5 pages; Moses is his control for a four page dissertation entitled ‘The Slandering’ (die Verleumdung), written in Hebre; Harun el Raschid makes him write 15 pages in Syrian: ‘Allah and his Prophets’, which required 22 minutes and thus down the list, his most extensive work mentioned being 40 pages written in Italian about ‘Loving your Neighbor’ in 90 minutes, and the most odd feature mentioned is an untranslateable [sic] writing of three pages in hieroglyphics which took 32 minutes.13Dingwall (1930), 304.

Altogether the Academy reported 392 sittings. Of these, 189 were for spoken mediumship (apparently all positive), 93 for automatic writing (of which 8 were negative), and 110 for physical phenomena (47 of which were negative). So 63 sessions were positive for physical phenomena. And of those, 40 were held in broad daylight and 23 in bright artificial light. Moreover, in those sessions Mirabelli was clearly visible to witnesses, sitting tied up in his chair, and in rooms searched before and after. Nevertheless, witnesses reported many occurrences which would seem to be impossible to produce fraudulently under those conditions.

For example, an arm chair, with Mirabelli seated in it and his legs under control, rose two meters above the floor, remained aloft for two minutes, and then descended 2.5 meters away from its original place. On another occasion, a skull rose into the air and began accumulating bones until it became a complete skeleton. Observers handled the skeleton for a while until it began to fade away, leaving the skull to remain floating. Soon thereafter, the skull fell onto the table. Mirabelli was bound throughout the event, which lasted 22 minutes in bright daylight. One of the sitters confessed later that when the skull initially rose into the air, he had mentally asked whether the rest of the skeleton would appear.

Another materialization is so astounding that Dingwall’s description deserves to be quoted in its entirety.

Phenomena began by an odor of roses which filled the room, and after a few minutes a vague cloudy appearance was remarked forming over an arm-chair.All eyes were rivetted upon this manifestation and the sitters observed the cloud becoming thicker and forming little puffs of cloudy vapour. Then the cloud seemed to divide and move towards the sitters floating over them and condensing while at the same time it revolved arid shone with a yellowish golden sheen. Then a part divided and from the opening was seen to emerge the smiling form of the prelate, Bishop Camargo Barros, who had been drowned in a shipwreck. He was wearing his biretta and insignia of office and when he descended to earth he was minutely examined by a medical man. His respiration was verified and the saliva in his mouth examined: even the inner rumblings of the stomach were duly heard and noted. Other sitters also examined the figure and fully satisfied themselves that they were not the victims of illusion or disordered imagination. The Bishop then addressed them and told them to watch carefully the mode of his disappearance. The phantom then approached the medium who was lying in his chair in a deep trance, and bent over him. Suddenly the body of the phantom appeared to be convulsed in a strange manner and then began to shrink and seemingly to wither away. The medium, controlled by the sitters on either side, then began to snore loudly and-break into a cold sweat, whilst the apparition continued to draw together until it was apparently absorbed and finally disappeared. Then again the room was pervaded by the sweet odor of roses.14Dingwall (1930), 299.

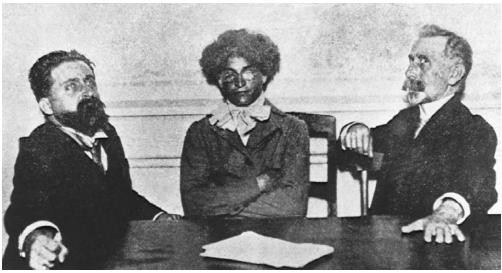

Fig. 1: Dr. Carlos de Castro (right) seems alarmed at finding the deceased poet Giuseppe Parini between himself and the entranced Mirabelli.

At another sitting, Mirabelli, tied to his chair with bonds sealed, disappeared from the séance room and was found later in another room, ‘though the seals put on his bonds were intact, as were the seals on all the doors and windows of the séance room.’15Inglis (1984), 226.

Perhaps the most famous of Mirabelli’s disappearances was his apparent spontaneous transportation from São Paulo’s Luz train station to São Vicente, about 50 miles away. He simply vanished from the platform, where he had been standing among friends. After about 15 minutes, his concerned friends got through by telephone to the home where they had all been heading, and were told that Mirabelli had been there for the past 15 minutes.

Testimonies

Mirabelli was a polarizing figure for Brazilian Spiritism, especially because he was somewhat flamboyant and self-aggrandizing, and accepted substantial fees for his services. It is worth noting, then, that some of the testimony in Mirabelli’s favor was provided by witnesses predisposed against the medium. Perhaps the most important account is that of Carlos Imbassahy, ‘a highly orthodox Spiritist…[who] regarded Mirabelli as either a vulgar fraud, a skilful conjuror, or at most a medium who had got mixed up in the wrong company, both incarnate and discarnate.’16Playfair (2011), 47.

Imbassahy was at home one day with a businessman friend, Daniel de Brito, when another friend arrived along with Mirabelli. Imbassahy reports that there was nobody he less wanted to see than Mirabelli. Characteristically, the medium made himself comfortable and started speaking in ‘detestable Italian mixed with Portuguese and Spanish words’,17Quoted in Playfair (2011), 47, from Imbassahy (1935). purportedly from Cesare Lombroso. After that, he turned to de Brito and ‘proceeded to give the startled businessman an account of his [Brito’s] life from the cradle onwards. Brito had never met him before, and was not a well-known figure himself, but the medium seemed to know all there was to know about him. Imbassahy was reluctantly impressed.’18Playfair (2011), 47.

Mirabelli often would ‘magnetize’ water as part of a ritual for his many efforts at mediumistic healing. So when he learned that someone in Imbassahy’s house was ill, he asked for some bottles of water, which a maid promptly brought and placed on a table four or five meters away from the medium. The four men joined hands to form a ‘current’; light in the room was provided by two 100-watt bulbs; only the maid touched the bottles; Mirabelli had no time to prepare trick; and his hands were held during the phenomena that followed. Imbassahy reports:

Immediately, in full view of us all, one of the bottles rose half way up the height of the others, and hit them with full force for five or ten seconds, before returning to its place. We thought they must have been cracked. This was clearly seen and heard, with no shadow of hesitation. People in the next room also heard it, and the patient became extremely alarmed!19Quoted in and translated by Playfair (2011), 47.

Imbassahy reluctantly concluded that Mirabelli had genuine mediumistic gifts, although he continued to disapprove of him personally.

European and American Investigations

Eventually, news about Mirabelli began to spread more widely beyond the borders of Brazil, and at that point veteran American and European researchers began taking an active interest. In August 1928, philosopher and SPR president (1926-27) Hans Driesch, sat with Mirabelli, and later wrote a letter recounting his experiences.20Driesch (1930).

Driesch was clearly unimpressed with the linguistic productions he observed. Mirabelli spoke Italian (in which Driesch was fluent) as if the medium’s father were speaking through him. But Driesch wrote: ‘There was not the slightest idea of a “trance” and I believe the whole affair was not at all genuine, but a comedy.’21Driesch (1930), 486. Later, Mirabelli seemed to speak Estonian. He had brought a young Estonian girl with him, but Driesch could not believe that the girl’s father was really speaking through the medium. He assumed instead that Mirabelli had probably learned some Estonian.

However, Driesch was somewhat more sympathetic regarding Mirabelli’s physical phenomena. As the company entered the hostess’s dressing room, ‘Mirabelli cried and said some prayers and then, suddenly, a small vase on one of the tables began to move and finally fell down. I could not observe any sort of mechanical arrangement such as a wire or string or otherwise.’22Driesch (1930), 487.

Driesch was highly suspicious of several apports that occurred on this occasion, especially since Mirabelli wore a large overcoat ‘with enormous pockets’.23Driesch (1930). Driesch, Mirabelli, and their hostess stood on a veranda whose windows were closed (and on which there was therefore no wind), and other members of the company stood inside the adjacent drawing room. Mirabelli began to pray for sign, and then the open folding doors between the veranda and drawing room slowly closed. ‘This was seen at the same time by the persons in the drawing room and those on the veranda. It was rather impressive, and no mechanical arrangements could be found.24Driesch (1930). But Driesch added, cautiously, ‘Mirabelli had been in Pritze’s villa already about an hour before we arrived, alone with Frau Pritze. He may have made some arrangement before we came—I do not say that he did.’25Driesch (1930).

In January 1934, May Walker from the American Society for Psychical Research had sittings with Mirabelli and published a short and favorable report soon after.26Walker (1934). For the first sitting

There were four phenomena in all, witnessed in good white light sufficient to see each person clearly and also all the objects in the room. My camera, with which I had just taken a photograph of the medium, was lying on a long wooden table at some distance from where we were standing, holding Mirabell’s hands. It began to move about on the table and jumped on to the floor. A small fan laid on my upturned palms, began to wriggle about as if alive, then falling off. In this case, Mirabell’s fingers were near my hands, but not touching them and it almost seemed as if some magnetism issued from his fingers, causing the fan to move.

My hat, a large straw one, turned completely round on the table and three tall glass bottles filled with water all shook together. Later one of them fell over on its side. There was an interval of some minutes between each phenomenon.27Walker (1934), 75-76.

The second sitting took place in a private garden, ‘owing to the fact that so many things in the house had been broken by psychic means’.28Walker (1934), 76. It was held in the evening, ‘well lit by electric lamps’,29Walker (1934), 76. and most of the phenomena were apports, which Walker found moderately persuasive. However, she wisely preferred indoor phenomena, and the next evening her wish was granted.

The third sitting began with some object movements and an apport, the authenticity of which Walker was not prepared to endorse. But, she said,

Of the last phenomena, however, I had no doubts. All of us adjourned to the back room, where, on a table against the far wall, were about a dozen large wine bottles filled with water.

We formed a chain in a semi-circle at the other side of the room, Mirabelli being at one end of it, but a considerable distance from the table. He asked for a sign that the water had been magnetized—which I understand he thinks is done by his father, who has passed over.

Immediately came the jingling together of the bottles;— then a loud noise which shook them still more, as if some one has rapped on the table. After a slight pause, one bottle fell over on its side.30Walker (1934), 76.

Regrettably, Walker does not indicate why she was certain that the bottles had not been prepared somehow in advance. In any case, she concluded that Mirabelli had presented her with ‘the best telekinesis I have ever seen.’31Walker (1934), 78.

Later the same year (in August), the SPR’s Theodore Besterman visited Mirabelli. By this time Besterman had already established himself as critically cautious but open-minded with regard to at least moderate-scale demonstrations of physical mediumship. For example, his often-cited study of slate-writing showed that under certain (rather poor) séance conditions and for certain kinds of small-scale ostensibly paranormal phenomena, subjects can err in their observations and sometimes report events that never occurred.32Besterman (1932b). But Besterman was also prepared to endorse the carefully obtained evidence for Rudi Schneider’s ability to deflect an infrared beam.33Besterman (1932a).

However, when it came to Mirabelli, it seems that something simply rubbed Besterman the wrong way, from the start. In fact, it may be that he was predisposed to distrust Mirabelli, because four years earlier he had skeptically reviewed the published accounts that were available at the time.34Besterman (1930).

At any rate, during his visit to Brazil, Eurico de Goes, ‘one of Brazil’s first serious psychical researchers’,35Playfair (2011) 24. took minutes of the several sessions (at least five) which Besterman attended. According to those minutes,

flowers materialized, bottles on a table jumped around, one even hopping onto the floor, a picture left the wall to float in mid-air and land abruptly on someone’s head, a chair slid along the floor for about ten feet, the front-door key drifted out of its lock, and Mirabelli came up with a learned written discourse in French, writing nearly 1800 words in 53 minutes.36Playfair (2011), 27.

Initially at least, Besterman seemed to be impressed. De Goes quoted him in English as having said ‘Mr Mirabelli’s phenomena [are] of the greatest interest… Many of them were unique of their kind.’37Playfair (2011). Notice that this quote does not endorse the phenomena as authentic, and it does not contradict his earlier skeptical review of the published accounts of Mirabelli. So it is not really surprising that by the time Besterman wrote his 1934 report for the SPR Journal, he showed little if any enthusiasm for what he had observed in Brazil. Indeed, in his often sarcastic and condescending report he accused Mirabelli of fraud and provided some examples of phenomena he believed to have been faked.

Significantly, in Besterman’s sessions, Mirabelli did not allow the sorts of controls reported in some of the most striking cases mentioned earlier—for example, binding Mirabelli to an armchair and sealing the bonds. Besterman reported that it was clear he was allowed to be no more than a spectator, and he remarked, ‘No sort of control was at any time exercised, suggested or asked for by any sitter other than myself, and then without success.’38Besterman (1935), 144. Séances were held in the evening, with illumination varying from complete darkness to bright electric light from seven or eight uncovered bulbs.

The largest group of phenomena witnessed by Besterman were apports, which Besterman claimed ‘were undoubtedly all faked’39Besterman (1935), 145. and facilitated by obvious methods of distraction and occasionally by darkness as well. Besterman also reported moving bottles of ‘magnetised’ water, similar to what Walker had reported months earlier. However, in Besterman’s case, the phenomenon occurred in darkness. Not surprisingly, Besterman conjectured that Mirabelli looped a black thread around the moved bottle (rather than attaching it to the bottle) so that it could be easily retrieved.

After briefly mentioning and dismissing some other minor physical phenomena, Besterman then reported two other examples in detail. The first does, indeed, seem to have been a simple conjuring trick, as Besterman noted. Besterman described the performance as follows:

[Mirabelli] went into another room accompanied by [one of the sitters], there, we were told, held the coin in his open palm, with the sitter’s open palm over it. The coin then vanished, Mirabelli returned to the room in which we were sitting, and asked me where I wanted the coin re-materialised. I elected for my own pocket and in a moment or two Mirabelli announced that the coin had been precipitated into my breast-pocket; there I duly found it. This performance was repeated with each of the male sitters present, with success, except that on one occasion I ventured correctly to forecast to my neighbour where the coin would be found. It must be noted that at no time during the progress of this phenomenon did Mirabelli approach within three yards of the main body of sitters.40Besterman (1935), 147.

As Besterman correctly observed,

The way this trick was done was simple in the extreme. At a given moment, before the lecture, Mirabelli asked the male sitters one by one into an adjoining room, where he examined them ‘magnetically’, making passes over them, etc. While doing so he slipped a coin into the pocket of each ‘patient’. The vanishing of the coin is of course elementary palming, and the rest is obvious. All that is required is unlimited impudence and a sufficient number of similar coins. What first aroused my suspicion was this: when asked to examine the 1869 coin I did examine it and made a mental note of its characteristics. When I found the coin in my breast-pocket I immediately saw, from minute characteristic marks, that it was not the same one, and the rest was then obvious. Again, every coin was found in an outside breast-pocket except X’s, who had his materialised into his hip pocket, and X had been the only ‘patient’ who had been asked to take his jacket off, as I happened by chance to notice.41Besterman (1935).

Besterman claimed that only one phenomenon during his sittings was ‘really impressive’. This was the turning of a blackboard placed on the top of a bottle, occurring in bright light sufficient for filming the event, and with the medium and sitters holding their hands over the board. This occurred twice, and Besterman found that he could not duplicate the effect by blowing on the board. He was also certain that no threads were used. He wrote:

I am still puzzled by this phenomenon; taking into account the good light, the fact that Mirabelli performs the phenomenon completely surrounded by standing ‘sitters’, who seem to have complete liberty of movement, and the fact that he expressed no objection whatever to the filming, although I strongly emphasised the fact that the camera and the film were very special ones and would show every detail, the fact that Mirabelli allowed me on each occasion to arrange the mise en scène and did not precipitate himself on the board as it fell, the fact that the room, the table, and the bottle were all different, though the board was the same, all these circumstances make the hypothesis of threads practically impossible, while any other fraudulent method is difficult to conceive.42Besterman (1935), 148.

Besterman’s report elicited a sharply critical response from Dingwall,43Dingwall (1936). claiming that Besterman did little more than ‘bringing back stories of silly tricks’.44Dingwall (1936), 169. His remarks criticized not only Besterman’s negative appraisal of Mirabelli, but his positive views as well, and are worth excerpting.

Mr Besterman has come to a surprising conclusion. He thinks that there is a prima facie case that Mirabelli may possess some paranormal ‘faculty’, and this is based on the fact he was unable to detect the modus operandi of a revolving blackboard effect. Apart from the fact that there was no reason why he should have been able to understand it, are we expected to believe…that because…[Mr Besterman] could not and cannot discover how certain conjuring tricks are done there is a prima facie case for the successful performers possessing ‘paranormal’ faculties? It is this that makes psychical research ridiculous, and rightly so.

In my account of Mirabelli, which was printed in 1930 by the A.S.P.R., I described certain phenomena and named the parties who were said to have been present… Did Mr Besterman interview any one of these persons? Did he talk to any of the sitters who are recorded as being present at the alleged materializations of Bishop Barros, Prof. Ferreira, or Dr de Souza’s daughter? To say that their testimony ‘is of relatively little value’ is beside the point. It is as valuable as that of Mr Besterman, since what they record is quite as striking as anything with D. D. Home. Do these witnesses exist? Were they present at these sittings? Were they lying or are they made to record phenomena which never took place at all? Or must we admit that certain ‘events took place which were described by those who witnessed them in the terms we have read’? What were those events? I wrote these words in 1930. No answer has been attempted. Yet in 1934, at heavy cost to the S.P.R., Mr Besterman goes to South America ostensibly to inquire into what he terms Mirabelli’s ‘astounding feats’ and comes back with tales of revolving objects which puzzled him.

The problem of Mirabelli is the same as that of Home. In the latter case the witnesses are dead and cannot now be interviewed: in the former case they are living and can be seen and cross-examined. Signed statements by Dr G. de Souza, Dr Moura or Dr Mendonça describing in their own words what they saw on certain occasions as recorded in 0 Medium Mirabelli would be worth far more than stories of revolving blackboards and jumping cameras which puzzled observers who would be equally puzzled by 90% of conjuring tricks performed by even moderately skilled artistes.45Dingwall (1936), 169-70.

To this, Besterman responded simply that Dingwall’s criticisms called ‘for little comment’.46Besterman (1936), 236. But Dingwall was justified in complaining that Besterman made no effort to follow-up on the most intriguing eyewitness reports of dramatic phenomena under good controls.

Fortunately, Playfair was able to interview some of the surviving sitters at Mirabelli’s séances, and that information informs his detailed account.47Playfair (2011). Playfair also generously concedes: ‘it must be said that little useful research can be done in two or three weeks in Brazil even today, and even when one speaks Portuguese, as I do and he did not.’48Playfair (2011), 44.

So readers should keep in mind that Besterman claimed never to have observed the most dramatic phenomena on which Mirabelli’s fame largely rests, and it should be mentioned again that he never observed the medium submitting to the seemingly good controls so often reported by others during those events. This is somewhat reminiscent of a feature of the case of Eusapia Palladino, whose most impressive phenomena often occurred under the most stringent controls,49See, for example, Feilding (1963); Feilding et al (1909). and who had few if any reservations about cheating when conditions were looser, or when she disliked her investigators, or when she was lazy, or when the ‘force’ was weak.50See the discussion of Palladino in Braude (1997).

However, as Playfair noted, Besterman may indeed have witnessed something more spectacular and less amenable to charges of chicanery. He may have intentionally failed to report an apparently impressive materialization. This was evidently not a full-form materialization, but rather ‘radiations… on a corner of the table’.51de Goes (1937), 125. Playfair reports:

At the very first meeting, according to the minutes [of the séances], Mirabelli announced that he could see an entity named Zabelle, whom he described in detail. Besterman said he had known a lady of that name in London who was now dead, and when he asked for a sign of her presence, bottles began to jump around on a table, one of them even falling on to the floor at his request. Besterman mentions the bottles, but not the mysterious Zabelle.

At the second meeting, Zabelle again dropped in and became visible enough for Dr Thadeu de Medeiros to take a photograph of her. This is reproduced in de Goes’s book, and is one of the more credible materialization photographs I have seen… According to the minutes, which de Goes reports Besterman as having signed, Zabelle performed a number of feats to prove her presence.

In the minutes of the third meeting, we are told that Besterman examined the photograph of Zabelle and declared that there was a strong resemblance to the lady he had known. The face on the photograph is extremely clear, more so than in most pictures of this kind.

Fig. 2: Apparent materialization of Zabelle.

Besterman’s failure to mention these incidents is certainly surprising. De Goes’s minutes claim that at the first of the three meetings ‘Besterman… confessed that he had never seen anything so interesting.’52de Goes (1937), 105. Playfair correctly observes,

It is surprising that Besterman makes no mention of this episode. It is clear from his lengthy published report that he was anxious to miss no opportunity to discredit Mirabelli’s powers, and if the Zabelle story were untrue, here was an excellent opportunity to do so. If, on the other hand, it was true, then Besterman is guilty of suppressing strong evidence in favour of the medium.53Playfair (2011), 45.

The Phantom Ladder

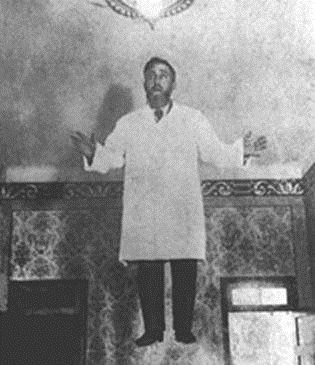

However, if one wants to find evidence of Mirabelli cheating in connection with his more spectacular manifestations, one need only consider the notorious photograph of Mirabelli allegedly levitating (see Fig. 3). This photo was published outside of Brazil for the first time in the first (1975) edition of Playfair’s The Flying Cow. In that book Playfair noted that he was unable to authenticate the photo, and that it might be faked.

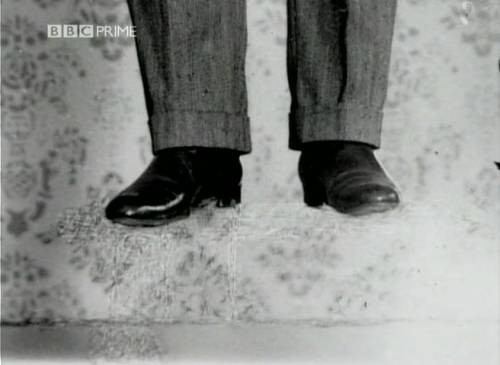

Confirmation came in 1990, when American researcher Gordon Stein found an original print of the photo in the SPR archives in the Cambridge University Library, showing clearly that the image had been retouched to remove the ladder upon which Mirabelli was standing. It is unclear whether the original negative had been retouched, or whether a print was manipulated and then re-photographed. But in any case, the evidence is clear (see Fig. 4), and Stein was undoubtedly justified in claiming that Mirabelli ‘knowingly passed off a fraudulent photo of himself as genuine’.54Stein (1991). Curiously, Mirabelli had signed the print and inscribed it ‘To Mr Theodore Besterman’. And equally curiously, Besterman—clearly no fan of Mirabelli—failed to seize the opportunity to mention the obvious fraud in his report. At any rate, Playfair was also quick to publish a paper discussing the discovered fraud, and he updated the account of Mirabelli in a later edition of his book.55Playfair (1992, 2011).

Fig. 3: Photograph showing Mirabelli apparently levitating

Fig. 4: The signs of retouching the photo to hide the ladder.

Conclusion

Obviously, the case of Mirabelli must be regarded, at best, as one of mixed mediumship. Equally obviously, and as the case of Palladino illustrates clearly, one cannot plausibly argue that a person who cheats once will cheat all the time. Indeed, as noted above, there can be obvious (and perhaps even defensible) reasons for a medium cheating occasionally. In fact, an irony of the Palladino case is that her willingness to cheat when allowed set the stage for the most convincing and stringently controlled séances in her career—the 1908 Naples sittings.

Moreover, the fact remains that many of Mirabelli’s apparently well-attested and decently controlled manifestations resist easy—or any—sound skeptical dismissal. Certainly, Besterman’s exposure of – and conjectures about – conjuring trips under no controls fails to address the challenge posed by the much more spectacular physical phenomena reported in Mirabelli’s case. So although the phenomena of Mirabelli are perhaps not as well-established as, say, the most compelling phenomena of DD Home, Eusapia Palladino, Franek Kluski, and others, good reasons remain for taking the case seriously, and perhaps for regarding it as an indication of just how dramatic PK phenomena can be.

Stephen Braude

Literature

Besterman, T. (1930). Review of Mensagens do Além obtidas e controladas pela Academia de Estudios Psychicos “Cesar Lombroso” atravez do celebre Medium Mirabelli. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 26, 142-44.

Besterman, T. (1932a). The mediumship of Rudi Schneider. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 40, 428-36.

Besterman, T. (1932b). The psychology of testimony in relation to paraphysical phenomena. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 40, 363-87.

Besterman, T. (1935). The mediumship of Carlos Mirabelli. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 29, 141-53.

Besterman, T. (1936). Letter to the Journal. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 29, 235-36.

Braude, S.E. (1997). The Limits of Influence: Psychokinesis and the Philosophy of Science (rev. ed.). Lanham, Maryland, USA: University Press of America.

de Goes, E. (1937). Prodígios da Biopsychica Obtidos com o Médium Mirabelli. São Paolo: Typographia Cupolo. (Reprinted in Coleção Mirabelli vol. 2, ed. M. Bellini. São Paulo: Centro Espírita Casa do Caminho Santana, 2016.).

Dingwall, E.J. (1930). An amazing case: The mediumship of Carlos Mirabelli. Psychic Research 34, 296-306.

Dingwall, E.J. (1936). Letter to the Journal. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 29 169-70.

Driesch, H. (1930). The mediumship of Mirabelli. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 24, 486-87.

Feilding, E. (1963). Sittings with Eusapia Palladino and Other Studies. New Hyde Park, New York, USA: University Books.

Feilding, E., Baggally, W.W., & Carrington, H. (1909). Report on a series of sittings with Eusapia Palladino. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 23, 309-569. Reprinted in Feilding (1963).

Imbassahy, C. (1935). O Espiritismo à Luz dos Fatos. Rio de Janeiro: FEB.

Inglis, B. (1984). Science and Parascience: A History of the Paranormal 1914-1939. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Playfair, G.L. (1992). Mirabelli and the phantom ladder. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 58, 201-3.

Playfair, G.L. (2011). The Flying Cow. Guildford: White Crow Books.

Stein, G. (1991). The amazing medium Mirabelli. Fate 44/3 (March), 86-95.

Walker, M.C. (1934). Psychic research in Brazil. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 28, 74-78.