Cock Lane in London was the scene of a notorious haunting that excited public interest during the winter of 1762. The reported phenomena of unexplained noises were typical of those described in many so-called ‘poltergeist’ cases. But the true facts were hard to discern amid the complex social background, and fraud was strongly suspected.

Background

In 1760 William Kent, a young stockbroker, rented a house in Cock Lane, a small street in the City of London. It belonged to Richard Parsons, a parish clerk and ‘heavy drinker with a tendency to run into debt’.1Smyth (1982), 1559. Other biographical details in this section taken from Grant (1965) and Chambers (2006). Kent paid his rent in advance and additionally gave Parsons a loan of twelve guineas. Kent moved into the house together with his late wife’s sister Fanny, with whom he had formed a relationship, the pair posing as a married couple.

One day, when Kent was away attending a wedding, Fanny and Parsons’s daughter Elizabeth heard knocking and scratching noises that seemed to have no obvious source.2Lang (1896), 164.

The Kents moved out when Parsons failed to repay the loan, moving to nearby Clerkenwell. Soon after this Fanny died from smallpox. Meanwhile, Kent successfully sued Parsons, who was forced to make the payment in January 1762.

Phenomena

At this time, the unexplained sounds, described as ‘knockings’ and ‘scratchings’ returned in Parson’s home and could not be stopped. Seemingly they were connected to Elizabeth, who was prone to convulsions. Parson invited a number of people to witness the phenomena. One visitor was John Moore, a Methodist minister, who held séances to question ‘Fanny’, adopting the method of one knock for ‘yes’ and two knocks for ‘no’. The responses seemingly indicated that Fanny had died not from smallpox, but by arsenic poisoning administered by Kent.3Mackay (1995), 609-10. Parsons now effectively accused Kent of murder. He claimed that loud knockings had been heard the night following Fanny’s death, while Elizabeth claimed to have seen ‘a shrouded figure without hands’.4Guiley (1994), 65.

Press reports circulated, referring to the incidents as ‘Scratching Fanny’. Large crowds gathered at the property, encouraged by Parsons, who charged them a fee to enter. It also attracted curious notables such as the writer Samuel Johnson, writer and politician Horace Walpole, and Prince Edward, younger brother of King George III, along with physicians, priests, and others.5Mackay (1995), 610.

Investigations

To try to get to the bottom of the affair, the City of London mayor Sir Samuel Fluyder ordered an investigation. A committee was formed that included Lord Dartmouth, Johnson and John Douglas, a known exposer of frauds.6Smyth (1982), 1574. The committee undertook a rigorous investigation of Elizabeth Parsons, carrying out séances in which attempts were made to observe the phenomena and communicate with the ghost.

A detailed statement was written by Johnson concerning a séance held on 1 February 1762 at the house of a local clergyman.7Boswell & Malone (1791), 220-21. Elizabeth having been put to bed ‘with proper caution by several ladies’, the committee failed to hear any noises emanating from nearby her and left the room. They were recalled some time later when the ladies claimed they had heard knocks and scratches, but still failed to hear anything themselves. On the assumption that the ghost was present, they informed it they were going to the vault in a local church, where they expected it to hold to its promise, apparently made on an earlier occasion, that it would knock on Fanny’s coffin. They heard nothing there either. The statement concludes:

Upon their return they examined the girl, but could draw no confession from her. Between two and three she desired and was permitted to go home with her father. It is, therefore, the opinion of the whole assembly, that the child has some art of making or counterfeiting a particular noise, and that there is no agency of any higher cause.8Boswell & Malone (1791), 221.

On 25 February 1762, a pamphlet probably written by Oliver Goldsmith was published under the title The Mystery Revealed; Containing a Series of Transactions and Authentic Testimonials respecting the supposed Cock Lane Ghost, which have been concealed from the Public. This declared Kent to be innocent.9Cited in Wilson (1981), 129.

Kent, meanwhile, took Parsons and his family to court, accusing them of attempting to murder him and of having poisoned Fanny. Parsons was sentenced to stand three times in the pillory and sent to prison for two years and his wife for one year. Their servant was imprisoned for six months for collusion.10Mackay (1995), 613.

Commentary and Controversy

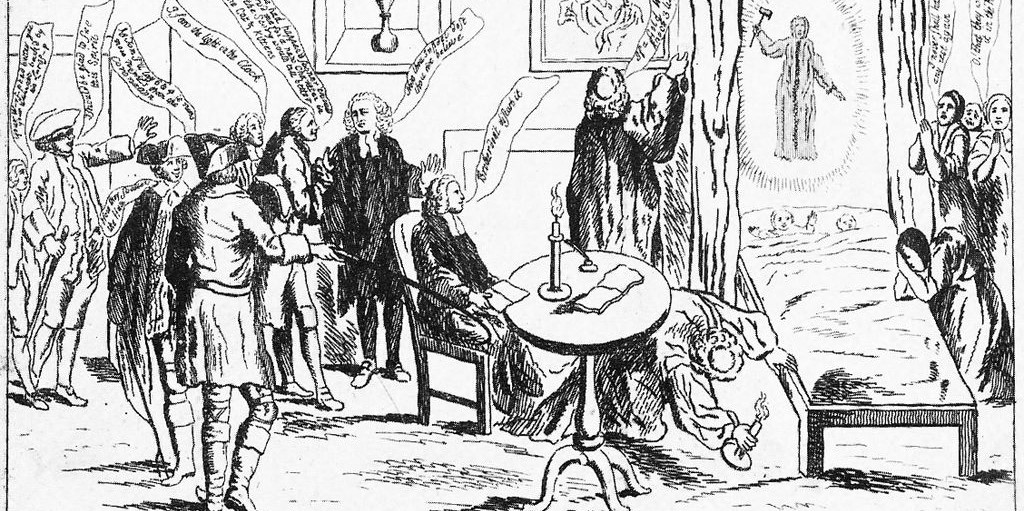

The Cock Lane ghost became a focus of religious strife between establishment Anglicans, who tended to frown on superstition, and dissenting Methodists, who embraced ghost stories as proof of an afterlife and who in this matter enjoyed much public support. This is referenced by Horace Walpole in his Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Third.11Walpole (1845). Satirical artist William Hogarth referred to the controversy in a drawing for The Times, in which supporters of the Methodists are linked with the Cock Lane Ghost. The affair is also referenced in his print Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism.

Charles Mackay drew from Goldsmith’s pamphlet describing the case in his 1841 book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. He considered that ‘[t]he precise manner in which the deception was carried on has never been explained.’12Mackay (1995), 613.

Charles Dickens referred to the Cock Lane ghost in Dombey and Son, in A Tale of Two Cities, where it features briefly on the first page, and in Nicholas Nickleby. In the last, Mrs Nickleby humorously suggests that her great-grandfather must have been at school with the Cock Lane ghost, ‘for I know the master of his school was a dissenter, and that would, in a great measure, account for the Cock-lane Ghost’s behaving in such an improper manner to the clergyman …’13Dickens (1839/1930), 560.

In the late nineteenth century the Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang referred to the case in the title of his survey of psychic phenomena, Cock Lane and Common Sense (1896). Lang felt it was impossible to draw any conclusions from the mass of stories relating to it.14Lang (1896), 179. He wrote:

If one phantom is more discredited than another, it is the Cock Lane ghost. The ghost has been a proverb for impudent trickery, and stern exposure, yet its history remains a puzzle, and is a good, if vulgar type, of all similar marvels … We still wander in Cock Lane, with a sense of amused antiquarian curiosity, and the same feeling accompanies us in all our explanations of this branch of mythology … but from the true solution of the problem we are as remote as ever.15Lang (1896), 161-62.

In the twentieth century author Colin Wilson, an advocate for the genuineness of psychic phenomena, stated, ‘Nothing could be more obvious than that the Cock Lane ghost was a poltergeist like the hundreds of others that have been recorded down the ages.16Wilson (1981), 130. Wilson spoke of the ‘universal sympathy’ said to exist for Parsons and criticized the refusal of the judges at his trial to take serious account of neighbours’ testimonies concerning the knocking sounds.

Historical accounts of the affair have been written by authors Douglas Grant, The Cock Lane Ghost (1965) and by Paul Chambers, The Cock Lane Ghost: Murder, Sex and Haunting in Dr Johnson’s London (2006). Chambers draws attention to the abundant sources available to researchers, including ‘nearly a hundred’ contemporary newspaper articles, ‘many of which are so scandal-laden that they would not be out of place in a modern red-top tabloid’, and a wide range of archived records that provide insights into the motives and characters of the people involved.

Chambers further writes:

As the pieces fell into place, a compelling true story began to emerge which contained many plots and subplots some of which could have come directly from a detective novel, others perhaps from a gothic horror, a comic farce or a love story. The central characters were no less varied. They were all colourful, forceful and, in most cases, deeply flawed. Some showed naivety, ignorance, cowardice or greed; others are vain, calculating, vengeful and even murderous. Add to this the volatile nature of eighteenth century London society and the story’s heady mixture of sex, murder and the supernatural and it is little wonder that I became so obsessed with it.

Melvyn Willin

Literature

Boswell, J., & Malone, E. (1791). The Life of Samuel Johnson (2nd ed). [Printed by Henry Baldwin, for Charles Dilly, in the Poultry.]

Chambers, P. (2006). The Cock Lane Ghost: Murder, Sex and Haunting in Dr Johnson’s London. Cheltenham, UK: History Press.

Dickens, C. (1839/1930). Nicholas Nickleby. London: Hazell, Watson & Viney Ltd.

Grant, D. (1965). The Cock Lane Ghost. London: St Martin’s Press.

Guiley, E.E. (1994). The Guinness Encyclopedia of Ghosts and Spirits. Enfield, UK: Guinness Publishing Ltd.

Lang, A. (1896). Cock Lane and Common Sense. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Mackay, C. (1841/1995). Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Ware, Herts, UK: Wordsworth Editions.

Smyth, F. (1982). The ghost and the gossips. The Unexplained 78, 1558-60; 79, 1573-75.

Walpole, H. (1845). Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Third , ed. by D. Le Marchant. London: Lea & Blanchard.

Wilson, C. (1981). Poltergeist! London: New English Library.