Henry Slade was a controversial nineteenth century seance medium who was publicly accused of fraud, but who was also reported to have produced striking psychokinetic phenomena under well-controlled conditions. This article examines the claims in detail, in particular experiments carried out by astrophysicist Johann Zöllner at the University of Leipzig.

Introduction

The case of Henry Slade is one of the more intriguing cases of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century mediumship. Witnesses reported that Slade produced a variety of physical phenomena, some as good as any produced by DD Home. However, he was controversial, and today he is primarily remembered as a trickster. To some extent, no doubt, that reputation has been deserved, because there is ample evidence that Slade cheated on occasion, perhaps especially in his declining years. Because the skeptical portrayal of Slade is the dominant one, Slade is now remembered primarily for (1) a farcical trial, (2) an alleged exposure by the Seybert Commission, and (3) the phenomenon of slate-writing. Let us consider these in reverse order.

Slate-writing was a method sometimes adopted during séances at this time, in which a piece of previously blank slate would be found to contain messages from ‘spirit communicators’. This, admittedly, is easy to fake, though not clearly so under some of the conditions imposed on Slade. Besides, Slade produced much more impressive phenomena. However, even some of the slate-writing seems difficult to dismiss. For example, the veteran investigator (and occasional assistant of William Crookes), Serjeant EW Cox, reported some intriguing occurrences in a sunlit room. The slate was placed on the table; Cox placed one of his own hands on the slate; Slade placed one hand on top of that; and Cox held Slade’s other hand. Even so, Cox felt the pressure on the slate as the writing was produced, and he could hear the writing as well. Afterwards, the slate was dragged from his hand and placed on his head, but the writing continued.1Reported in Inglis (1977), 278.

The Seybert Commission report is itself suspicious, for reasons similar to those in the case of Eusapia Palldino’s American investigations—namely, intentionally loose controls supervised by inexperienced investigators determined to expose fraud.2For details, see Inglis (1977), 364-69. And for comments on Palladino’s American investigations, see Dingwall (1962); Inglis (1977), 429-32; Inglis (1984), 26-27. Slade had produced some spirit writing on a slate for members of the Commission, and he left his demonstration feeling that he had been treated courteously and fairly, and in fact that he had done rather well. But when the Commission’s report came out, Slade discovered that his manifestations had been considered ‘fraudulent throughout’.

Inglis comments:

Why, if the tricks they had seen were ‘almost puerile in their legerdemain’, had they allowed Slade to leave with the impression that he had convinced them, or at least made them take slate-writing seriously … The method they had adopted was to allow him full liberty to cheat, and to show no sign if they caught him. One member, peeking under the table, had seen that Slade’s foot had been removed from its slipper. Another had seen that a supposedly clean slate had writing on it – though Slade, apparently realising he had been detected, had hurriedly cleaned it off. But by agreement these rules were not pointed out until the post-mortems which the members of the commission held after séances; so Slade was never actually caught red-handed.3Inglis (1977), 365.

In any case, some of Slade’s observed effects during the Commission’s investigation were never accounted for, or were explained away unconvincingly. For example, the well-known conjurer Harry Kellar tried explaining some of the slate-writing phenomena by appealing to a trap door constructed under the séance table and the additional assistance of a confederate in the room below. (Houdini unwisely endorsed this explanation.) But there simply was no trap door in this case. Slade conducted séances in whatever homes or hotels he happened to be, and the location used for the Commission’s investigation was no exception. However, the Commission never even mentioned Kellar’s conjecture—much less its manifest implausibility both in their own tests and as a general strategy for questioning the authenticity of Slade’s phenomena. The Commission’s silence on these matters seems, therefore, to have been a dishonest withholding of information that might have been used in Slade’s favour.

Finally, Slade’s trial is typically reported as a case in which Slade was convicted of fraud. But as a matter of fact, the testimony presented against Slade at the trial was weak in the extreme, and the judge based his verdict largely on the intuition that Slade’s phenomena could not possibly have been genuine because they conflicted with established natural laws.4See Inglis (1977) and Randall (1982), for details.

Testimony in Slade’s Favour

To be sure, Slade’s case is not documented as carefully or extensively as some others. But it is much stronger than sceptics allege, especially when the better and large-scale phenomena are considered. Indeed, several prominent and experienced investigators noted they were unable to explain away what they observed. For example, Lord Rayleigh visited Slade with a professional conjurer, and the conjurer claimed he was baffled.5Podmore (1902), vol. 2, 89 cites the report in the Glasgow Herald, 13 September 1876. And Frank Podmore, who was hardly sympathetic to physical mediums generally, also claimed that he was ‘profoundly impressed’ by the phenomena that occurred in his presence.6Podmore (1902), vol. 2, 89.

Slade was also studied by several other professional magicians who either admitted their inability to account for his phenomena or at least failed to account for them. For example, Frederick Powell, a member of the American Society of Magicians, sat with Slade in 1881-82. Powell’s impression of the medium was reported by none other than Houdini,7Houdini (1924). who (as an arch-sceptic of Spiritualist phenomena) ‘was unlikely to have invented a story redounding to a medium’s credit’,8Inglis (1977), 364. even if only to a small degree. Powell believed he knew how Slade might have produced some of his effects by trickery (though he admits he did not actually detect any cheating). But some phenomena he reported without offering any such conjectures. For example, he writes,

Once, while we were having our attention directed to a slate held by Slade, the unoccupied chair on the side opposite to Slade and almost at the side of Capt. Carter, suddenly rose so that its seat struck the underside of the table, and then fell back with quite a thud.

Another telling effect was carried out, when Slade gave me one of the small slates telling me to hold it under the table. I did so and felt it suddenly snatched from my hand (I was holding it with one hand, my other hand was on the top of the table) and carried with a scraping noise to the very end of the table and there it rose above the surface enough to disclose about a third or possibly a half its length. Then it was carried swiftly back and put in my hand.9Houdini (1924), 91.

Perhaps the most important testimony from a magician came from the noted conjuror,10In fact, Court Conjuror to the Emperor of Germany. Samuel Bellachini, who provided Slade with a witnessed affidavit, in which he claimed:

I must, for the sake of truth, hereby certify that the phenomenal occurrences with Mr. Slade have been thoroughly examined by me with the minutest observation and investigation of his surroundings, including the table, and that I have not in the smallest degree found anything to be produced by means of prestidigitative manifestations, or by mechanical apparatus; and that any explanation of the experiments which took place under the circumstances and conditions then obtaining by any reference to prestidigitation, to be absolutely impossible.11Zöllner (1888/1976), 214, (italics in original).

Zöllner’s Experiments

As with other cases of mediumship, the best way to evaluate Slade’s case is to focus on the strongest and most recalcitrant pieces of evidence (a procedure often and conveniently avoided by skeptics). Granted, slate-writing was perhaps the most popular of Slade’s phenomena. But that may be because the phenomena were ostensible spirit communications and because the majority of those interested in Slade were concerned with the possibility of postmortem survival. Slade’s other phenomena, however, are not so easy to dismiss. They were frequently large-scale and were produced in daylight or strong artificial light, and under good controls.

Slade’s principal and most creative investigator was Johann Zöllner, a physicist and astronomer at the University of Leipzig, who (like Slade) has been unjustly (and sometimes absurdly) maligned. Zöllner’s work with Slade began in December, 1877, and it was far from incompetent; indeed, it is often quite ingenious.12Zöllner (1888/1976). Sympathetic, but sober, discussions of this work can be found in Inglis (1977) and Randall (1982). Zöllner conducted more than 30 sessions with Slade, occasionally with the aid of prominent colleagues at the University of Leipzig—for example Wilhelm Scheibner, Professor of Mathematics, Wilhelm Weber, Professor of Physics, and Gustav Fechner, Professor of Physics and pioneer of the new science of psychophysics.

Slade’s principal and most creative investigator was Johann Zöllner, a physicist and astronomer at the University of Leipzig, who (like Slade) has been unjustly (and sometimes absurdly) maligned. Zöllner’s work with Slade began in December, 1877, and it was far from incompetent; indeed, it is often quite ingenious.12Zöllner (1888/1976). Sympathetic, but sober, discussions of this work can be found in Inglis (1977) and Randall (1982). Zöllner conducted more than 30 sessions with Slade, occasionally with the aid of prominent colleagues at the University of Leipzig—for example Wilhelm Scheibner, Professor of Mathematics, Wilhelm Weber, Professor of Physics, and Gustav Fechner, Professor of Physics and pioneer of the new science of psychophysics.

Zöllner had not been especially interested in Spiritualism, but he had some familiarity with reports of materialization and dematerialization, and he recognized that those phenomena might help him obtain experimental evidence of the existence of a fourth dimension. The most convincing evidence of that, he said, would be ‘the transport of material bodies from a space enclosed on every side’.13Zöllner (1888/1976), 135.

As a step in that direction, Zöllner conceived of several clever tests of Slade, all of which he thought could provide experimental evidence of a fourth dimension:

First, ‘Two wooden rings, one of oak, the other of alderwood, were each turned from one piece’.14Zöllner (1888/1976), 97.Zöllner hoped that the rings could be linked. He recognized that they could not be interlinked without detectable evidence of their having been cut and rejoined. And since the rings were made from different kinds of wood, that ruled out the possibility of their having been created together from the same piece of wood.

Second, Zöllner obtained snail shells of different species and sizes, hoping that the right or left spiral twist of the shells might be reversed in the fourth dimension.

Third, Zöllner cut a band without ends from dried gut, forming a loop of 40cms, ‘Should a knot be tied in this band, close microscopic examination would … reveal whether the connection of the parts of this strip had been severed or not.’15Zöllner (1888/1976), 97.

Fourth, Zöllner had a glass manufacturer produce a hollow glass ball, totally enclosed, with a diameter of 4 cms. He then cut a piece of paraffin candle with sharp edges, and of a size that could in principle fit within the glass ball. Zöllner reasoned that if the paraffin appeared, as is, within the ball, it would be inexplicable in terms of received science, because ordinarily, paraffin placed within blown glass would be melted by the heat of the glass.

As things turned out, none of those four tests worked as planned. But some related events occurred that seem just as significant as the results Zöllner had hoped for.

In a session on 3 May 1878, Zöllner placed two of the recently purchased snail shells on the table, one of which was small enough to be concealed by the other. He and Slade sat at the table, and Slade (as usual) held a slate underneath the table in order to receive writing. Shortly thereafter ‘something clattered suddenly on the slate, as if a hard body had fallen on it.’16Zöllner (1888/1976), 102. Slade then removed the slate, and the smaller of the two shells was found on top. Zöllner noted that ‘Since both shells had had lain before almost exactly in the middle of the table, untouched and constantly watched by me, here was, therefore, the … so-called penetration of matter confirmed by a surprising and quite unexpected physical fact.’17Zöllner (1888/1976), 102. Moreover, and at least as important, the transported shell was found to be almost too hot to touch. That observation was confirmed by Zöllner’s friend Oscar von Hoffmann, who also attended that session. The significance of this is twofold. First, it connects with many similar reports about apported objects in poltergeist cases. Second, it also undermines the skeptical proposal that Slade had surreptitiously picked up the shell, palmed it, and placed it on the slate. That procedure would not have heated the shell to such a high temperature.

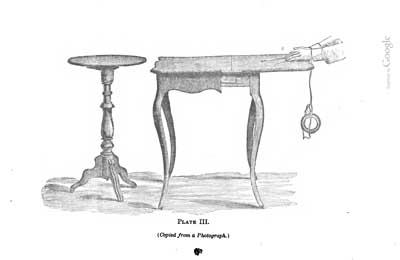

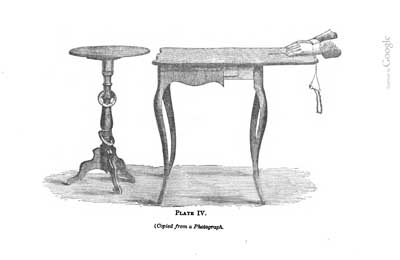

Equally remarkable is what happened the following week, on 9 May at 7 pm. The ‘room, which has a westerly aspect, was brilliantly lighted by the setting sun’.18Zöllner (1888/1976), 102. The aforementioned two wooden rings and the continuous loop of gut were strung on piece of catgut 1 mm thick and 1.05 meters long. The two ends of the catgut were knotted and sealed with Zöllner’s personal seal. After Slade and Zöllner sat at the table, Zöllner covered the sealed end of the catgut with his hands, and the rest of the catgut hung over the edge of the table onto Zöllner’s lap. Another, smaller round table was placed near the séance table shortly after the men entered the room. (See the arrangement in Plate III.)

Zöllner continues:

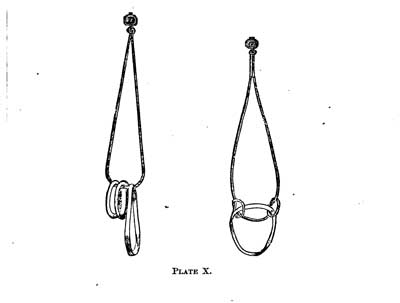

After a few minutes had elapsed, and Slade has asserted, as usual during physical manifestations, that he saw lights, a slight smell of burning was apparent in the room, – it seemed to come from under the table, and somewhat recalled the smell of sulphuric acid. Shortly afterwards we heard a rattling sound at the small round table opposite, as of pieces of wood knocking together. When I asked whether we should close the sitting, the rattling was repeated three times consecutively. We then left our seats, in order that we might ascertain the cause of the rattling at the round table. To our great astonishment we found the two wooden rings, which about six minutes previously were string on the catgut, in complete preservation, encircling the leg of the small table. The catgut was tied in two loose knots, through which the endless bladder band was hanging uninjured, as seen in Plate IV. (See also Plate X.)

Zöllner reports many additional interesting Slade phenomena, many of which matched those of DD Home both in style and in magnitude. They included: materialized hands,19Zöllner (1888/1976), 58, 86-89. occasionally violent large object movements (e.g., a filled bookcase) at a distance,20Zöllner (1888/1976), 56. accordion phenomena,21Zöllner (1888/1976), 57-58. and (as already noted) apports (including the disappearance and reappearance of objects)22Zöllner (1888/1976), 91-93, 102-10, 135-47. and the tying of knots in untouched endless cords.23Zöllner (1888/1976), 41-43, 82-86, 102-10.

Zöllner was an early proponent of the idea that skeptics err in their attempts to impose antecedently tight conditions on the mediums they investigate. He wrote:

For the characteristic of natural phenomena is that their existence can be confirmed at different places and times. Thus is proof afforded that there are general conditions (no matter whether known or unknown to us, or whether we can provide them or not at pleasure) upon which these phenomena depend. It is in the discovery and establishment of these conditions under which natural phenomena occur that the task of the scientific observer and experimenter consists.24Zöllner (1888/1976), 122, (italics in original).

Thus, Zöllner believed that the job of the scientist is to discover empirically the general conditions conducive to the phenomena, rather than to decide in advance which conditions should be imposed on the scientist’s human subjects.

In a similar vein, he proposes to

discuss the question how far it is justifiable and reasonable in dealing with new phenomena, the causes of which are entirely unknown to us, to impose conditions , under which these new phenomena should occur. That for the production of electricity by friction on the surfaces of bodies the driest possible air is requisite, and that in a damp atmosphere these experiments fail entirely, are also experimental conditions, which could evidently not he prescribed a priori, but have been discovered only through careful observations among those relations under which Nature in individual cases willingly offers us these phenomena.25Zöllner (1888/1976), 72, (italics in original).

Finally, it should be noted that the Seybert Commission successfully attempted to discredit Zöllner, five years after the scientist had died in 1882. After a visit to Leipzig, George Fullerton, the Commission’s Secretary, issued a statement claiming that Zöllner was ‘of unsound mind’ when he studied Slade, and ‘anxious for experimental verification of an already accepted hypothesis’. He also maintained that the testimony of Zöllner’s colleagues, Fechner, Weber, and Scheiber, could be ignored, owing to their age and physical deterioration. Fullerton thereby tried to create the impression that ‘the Leipzig experiments had been conducted by a group of infirm old men led by a lunatic’.26Randall (1982), 110. For further details, see Inglis (1977), 366 ff. Although Zöllner’s friends rose to his defense, their protests had little effect on public opinion. Today, Zöllner is seldom if ever mentioned in books on psychical research, and if he is mentioned at all, the comments are typically unfavourable.

Stephen Braude

Literature

Dingwall, E.J. (1962). Very Peculiar People. New Hyde Park, New York, NY: University Books.

Houdini, H. (1924). A Magician Among the Spirits. New York and London: Harper & Brothers.

Inglis, B. (1977). Natural and Supernatural. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Inglis, B. (1984). Science and Parascience: A History of the Paranormal 1914-1939. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Podmore, F. (1902). Modern Spiritualism: A History and a Criticism (2 vols). London: Methuen.

Randall, J.L. (1982). Psychokinesis: A Study of Paranormal Forces Through the Ages. London: Souvenir Press.

Zöllner, J.C.F. (1888/1976). Transcendental Physics (C.C. Massey, trans.). Boston/New York: Colby & Rich/Arno Press.