This is a well-verified case of the relatively uncommon ‘replacement reincarnation’ type, in which a child appears to die, then revives with a totally different personality and starts to speak of a previous life.

Contents

Jasbir Lal Jat

Jasbir Lal Jat was born in 1950 in the village of Rasulpur in northern India. At three and a half, he contracted smallpox and appeared to die, a typical occurrence in replacement reincarnation cases. As it was night-time his burial was postponed until morning. While waiting, the father noticed Jasbir’s body stirring, and eventually the child regained consciousness. It was some days before he could speak, and weeks before he could speak clearly, as he slowly recovered from the disease.

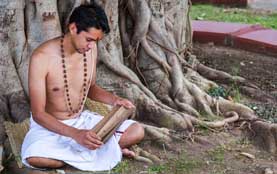

When Jasbir was again able to express himself, it was clear that his personality had entirely changed. He stated he was the son of Shankar of Vehedi village and wanted to return there. He refused to eat the food served him, saying he was a Brahmin, a higher caste than his family’s Jat caste, to the extent that he might have starved had not a Brahmin neighbour agreed to cook for him in the Brahmin manner. After about a year and half the family began to cook for Jasbir themselves, and discovering it caused him no harm he eventually joined them in their meals.

Describing his previous life, Jasbir said he had died after being given poisoned sweets at a wedding ceremony by a man who owed him money. The poison, he said, disoriented him while he was riding in a chariot during the post-wedding procession, causing him to fall off and die of a head injury.

Jasbir’s father tried to keep his son’s claims secret, but they nevertheless came to the attention of Brahmin village residents, one of whom was the wife of a man from Vehedi. While she was visiting Jasbir addressed her in a manner that would have been appropriate for his previous self, but entirely inappropriate to his current situation. She discussed the incident back in Vehedi, and it was eventually realized that the details described by Jasbir matched a recently deceased Vehedi resident, Sobha Ram, son of Sri Shankar Lal Tyagi, who died aged 22 in a chariot accident. The family knew nothing of their son being owed money, nor of him having been poisoned, although they had suspected it at the time.

Sobha Ram’s father and other family members visited Rasulpur, and Jasbir was able to recognize them and correctly identify his relationships with them. A few weeks later, a resident of Vehedi brought Jasbir there, and asked him to lead the way from the railway station to the Tyagi quadrangle, a gathering place for male family members, separate from the house. He did so without difficulty, and was also able to lead the way from another villager’s home to the Tyagi house. During a visit of several days, Jasbir revealed detailed knowledge of the family and its affairs.

Investigation

The case was investigated by reincarnation research pioneer Ian Stevenson and published in Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation.1Full case report: Stevenson (1974), 34-52. All information in this article is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted. Stevenson visited both Rasulpur and Vehedi in the summer of 1961, and interviewed thirteen witnesses including Jasbir Lal Jat, his parents, two brothers, uncle, the son of the Brahmin woman who had cooked for him, and other relatives and associates, as well as Sobha Ram’s father, two uncle, two brothers and son. Stevenson returned to both villages in 1964 to re-interview the same witnesses with a new interpreter, and interview some new ones. He found the accounts remained for the most part consistent over the three years, containing no greater number of errors than might be expected.

The two families both avowed to Stevenson that they had known nothing of each other prior to Jasbir’s speaking of his memories. As the two villages were about twenty miles apart and only accessible by dirt roads, the villagers tended to visit the larger town nearby rather than other villages; witnesses from each village told Stevenson they had barely heard the name of the other village. The caste difference also diminished the likelihood of prior contact between the families. Stevenson was satisfied by careful investigation that news of Sobha Ram’s death could not have reached Rasulpur by normal means.

Statements and Recognitions

Jasbir made the following statements about his former life that were verified as accurate by the witnesses interviewed:

- He was the son of ‘Shankar of Vehedi’ (Shankar Lal Tyagi’s son had died about the same time Jasbir made the statement).

- His name had been Sobha Ram (he said this only to his former father).

- There was a culvert, a water tunnel, in Vehedi (Rasulpur did not have one).

- There was a peepal tree in front of his house in Vehedi.

- His wife was from the village of Molna.

- He had a chariot he used to attend weddings (the Tyagi family still owned it at the time of the investigation).

- He had died while returning home from a wedding in Nirmana (a village about three miles north of Rasulpur), after falling from the chariot.

- The chariot was drawn by oxen, one white, with long horns, and one black, with short horns (though one witness disagreed about the colours and horns of the oxen).

- At the city nearby, Jasbir at age four pointed in the direction of Vehedi and said ‘my village is on this side’.

- There was a tamarind tree in front of the Tyagis’ courtyard (quadrangle).

- The Tyagi house had a well that was half inside and half outside the house.

- He had had a son named Baleshwar, an aunt named Ram Kali and a sister named Kela.

- His mother’s name was Sona, his mother-in-law’s was Kirpi, and his wife’s was Sumantra.

- When he died, he had ten rupees in a black coat inside a box.

- He had been bitten by a dog at a house to which he had gone to borrow a cot.

Jasbir’s claim that Sobha Ram had eaten poisoned sweets – and his identifying the murderer – were not verified. The Tyagis did not know whether he had eaten sweets prior to his death, but did recall he had eaten some betels.

Jasbir made the following correct recognitions of people and places, upon seeing them:

- the route between Vehedi and the town which his family took on shopping trips

- the way to the Tyagi quadrangle from the Vehedi railway station

- Sri Ravi Dutt Sukla, former native of Vehedi

- his past-life father, giving his name correctly

- his past-life paternal uncle

- his past-life younger brothers, giving one of their names correctly

- a neighbour of the Tyagi family who had acted unfairly in a dispute between the Tyagis and other neighbours

- his past-life maternal uncle

- his past-life son

- his past-life aunt

- people with whom the Tyagis were not on good terms

- his past-life brother-in-law

- his past-life grandfather, calling him by his old nickname also

Some recognitions were highly specific. For instance, he appeared to recognize his past-life younger cousin and addressed him as ‘Gandhiji’, but was corrected by someone present, as the cousin’s name was actually Birbal. Jasbir replied, ‘We call him “Gandhiji”’. This was correct: it was a nickname based on the cousin’s resemblance to Mahatma Gandhi.

It is also significant that Jasbir, having been taken outside the village and asked to identify which fields belonged to the Tyagi family, was able to point them out. Stevenson notes that one family’s holdings are often scattered around Indian villages.

There were no written records made of Jasbir’s remembrances prior to meeting the Tyagi family, but multiple witnesses gave consistent accounts.

Behaviours

As reported by his parents and other witnesses, following his transformation Jasbir strongly identified with his past incarnation, saying ‘I am the son of Shankar of Vehedi’. He also used a vocabulary more typical of Brahmin speech, such as the word haveli rather than hilli for house. Stevenson observed that he felt a strong attachment to the Tyagi family both in 1961 and 1964, and was particularly attached to Sobha Ram’s son. He threatened to run away to the Tyagi family at least once, and would cry at the end of his visits to Vehedi. He thought of himself as an adult with family and possessions in his former village; at the age of six he said to his mother when she was ill that if she needed money for treatment, he had some in Vehedi. During visits to Vehedi, he recognized people there with whom the Tyagis had quarrelled, and avoided speaking to them.

In 1961, Stevenson noticed that Jasbir would not play with other children in Rasulpur; his father reported that prior to his transformation he had enjoyed toys and play, but afterward appeared to have lost interest in them. In 1964, Stevenson noticed that Jasbir seemed more depressed than three years before, apparently frustrated by being unable to spend time in Vehedi: his family was reluctant to let him visit, worried that he preferred the Tyagi family to them. They said they had disbelieved his claims at first, but came to respect them when they were verified.

For their part, the Tyagi family entirely accepted Jasbir as the reincarnation of Sobha Ram.

Stevenson notes the evidentiary value of Jasbir’s behaviours and those of both families:

His personation of Sobha Ram, expressed in the pleasure of being with the Tyagis at Vehedi and the lonely isolation he experienced and showed in Rasulpur, provides some of the more impressive and more important features of the case. The reactions of the two families concerned matched this behaviour on his part, their tears and other emotions responding to his.2Stevenson (1974), 48.

Intermission Memory

In 1961, Stevenson asked Jasbir whether he had any intermission memories from between his death as Sobha Ram and the moment he entered his current body. He answered that after dying, he met a sadhu (holy man or saint) who advised him to ‘take cover’ in the body of Jasbir Lal Jat. When Stevenson asked him the same question again three years later, his memories had become confused; Stevenson speculated that this was the result of his trying to satisfy others who pressed him for details. His statements regarding life as Sobha Ram, however, remained consistent with what he had said previously.

Later Development

Stevenson was not able to meet Jasbir again until 1971, at which time he was twenty. He had attended school up until 1969 and was now helping his father cultivate his lands. He would visit Vehedi every three or four months, and on the last visit before speaking with Stevenson he had spent two and a half months there, working in the Tyagi family’s fields.

The Tyagis regarded Jasbir as a full member of their family, consulting him on the marriages of Sobha Ram’s son, whose wedding he attended, and one of his daughters. When asked who in Vehedi he was most attached to, he named Sobha Ram’s father and children (Sobha Ram’s mother had pre-deceased him).

Unusually for such cases, Jasbir said his memories had not at all faded, including the fall from chariot to his death and the exact spot where it occurred – a detail he had not previously mentioned in interviews. He continued to maintain he had been poisoned at the wedding ceremony by a man who was trying to avoid repaying a debt. (Stevenson says Jasbir named the individual, but does not give the name.) By this time the alleged murderer had paid Jasbir 600 rupees, a somewhat greater sum than the debt of 300-400 rupees Jasbir had spoken of in 1961. In fact Sobha Ram’s children, not Jasbir, were Sobha Ram’s legal heirs. Stevenson did not interpret this payment as admission of guilt, but, he writes, ‘we certainly can consider it as evidence of this man’s conviction that Jasbir was in fact Sobha Ram reborn’.3Stevenson (1974), 50.

Jasbir continued to retain Brahmin habits and attitudes: he considered Brahmins superior to other castes, refused to eat food cooked in earthen pots, and wore a sacred thread around his neck (which Jat caste members do not do). His family accommodated him by cooking in metal pans and allowing him to eat first. When Stevenson asked him for his mailing address, he gave his name as ‘Jasbir Singh Tyagi, son of Girdhari Lal Jat’ – acknowledging both his physical and past-life paternities. He expected to marry a Jat woman, however.

Jasbir said that in his dreams he still saw the discarnate sadhu who had advised him to enter his current body, and claimed that he had received from this figure accurate predictions of the future. Stevenson notes he later found other cases, notably in Thailand and Burma, where subjects remembered having received advice from a spiritual being during the inter-life period, who subsequently appeared to them in dreams.

In 1971, Stevenson noted a positive change in Jasbir’s demeanor compared to 1964. No longer depressed, he had grown into a ‘smiling, self-confident young man’.4Stevenson (1974), 52. Stevenson credited his current-life family for having helped him adjust. Jasbir said his older brother, who had been particularly hostile to his superior attitude, had now fully accepted him into the family.

Stevenson noted that Jasbir’s financial situation was difficult in 1971, and he considered himself demoted in this life from greater prosperity with the Tyagis – something Hindus believe results from sinful conduct in a past life. Jasbir could not recall anything he had done as Sobha Ram to deserve this, but the belief does not require the sin have been committed in the life immediately previous. He believed that divine will was responsible for his situation and accepted it.

Stevenson asked Jasbir what happened to the mind or personality that was apparently replaced by Sobha Ram’s. Jasbir answered that he did not know. Stevenson put out enquiries in the area as to whether any child claimed to have been one Jasbir of Rasulpur village who had died of smallpox, but never traced such a child.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Stevenson, I. (1974). Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation (2nd ed., rev.). [1st ed. 1966, Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 26, 1-361.] Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.