Jesse Shepard (1848–1927) was an outstanding musical performer who attributed his gifts to mediumship, and whose popularity with audiences in high society has led him to be compared with the medium DD Home, although he did not offer to relay messages from the dead. Like Home, Shepard did not charge for his performances, nor did he publish the works he performed. In later life he won critical acclaim as an essayist under the pen name Francis Grierson.

Life and Career

Shepard was born in 1848 as Benjamin Henry Jesse Francis Grierson Shepard, in Birkenhead, England, of Scottish/Irish parentage. He was taken to the US at an early age and grew up in Illinois. He started to play the piano at the age of twelve.

By his own account, at the age of 21, while attending a theatre performance in St Louis, a spirit called ‘Rachel’ came to him with advice to develop his singing. Accordingly, he visited a music professor who was impressed by the power of his voice and arranged for him to sing to an audience, which received his performance warmly.

Shepard then travelled to Paris, where his exceptional talents found wealthy patrons; his performances were in demand in high society. In 1871 he travelled to St Petersburg, where he played for the Czar. He returned to the US in 1874 and two years later performed at an old mission in San Diego. He later made his home there, building a grand mansion, the Villa Montezuma.

In the early 1880s he travelled to London, Berlin and Australia. His many patrons included the Queens of Denmark and Hanover, Prince Phillip of Bourbon and Braganza, Princess Marie of Hanover and the Viscountess Combermere.

Audiences were amazed to hear him apparently sing soprano and bass parts simultaneously. During a séance in Chicago the daughter of the medium Hudson Tuttle claimed that his spirit control sang one part while an Egyptian spirit sang the other.1Gaddis (1994). He sang in Saint-Eustache and the basilica of Montmartre by special invitation, and was chosen by composer Leon Gasinelle to sing the leading parts in his Mass written for the festival of the Annunciation and performed in the Cathedral of Notre Dame. His ability on the piano was considered even more awe-inspiring: he seemed to some to be have been variously possessed by the spirits of Mozart, Beethoven, Meyerbeer, Rossini, Sontag, Persiani, Malibran, Lablache, Liszt, Berlioz and Chopin.

Shepard claimed to speak only English and French, but in trance he was said to have addressed audiences in German, Latin, Greek, Chaldean and Arabic. During a séance at The Hague in 1907, it was reported that direct voices were heard speaking through him in Dutch, Sundanese (a Javanese dialect) and Mandarin Chinese.2Willin (2005).

In 1885, Shepard met Lawrence W Tonner who became Shepard’s secretary and friend for over forty years. They lived together in the Villa Montezuma. He became more involved in Spiritualism and Theosophy from this time, and also developed ties with the Catholic Church, turning away from music in favour of literary ventures, and used the house as a centre for grand receptions.Under the pen name Francis Grierson he published philosophical essays in The Golden Era, a West Coast journal that published much of Mark Twain’s early work. Their success encouraged him to move to France in 1888 to pursue a literary career.

Shepard finally settled in Los Angeles in 1920. In his last years he depended on Tonner for financial support. He continued writing and gave occasional piano recitals. He died at the keyboard while playing at a benefit dinner given for him on 29 May, 1927.

Testimonies

A report on his piano playing at a séance in Paris on 3 September, 1893, read as follows:

After having secured the most complete obscurity we placed ourselves in a circle around the medium, seated before the piano. Hardly were the first chords struck when we saw lights appearing at every corner of the room … The first piece played through Shepard was a fantasia of Thalberg’s on the air from ‘Semiramide’. This is unpublished, as is all of the music which is played by the spirits through Shepard. The second was a Rhapsody for four hands, played by Liszt and Thalberg with astounding fire, a sonority truly grand, and a masterly interpretation. Notwithstanding this extraordinarily complex technique, the harmony was admirable, and such as no one present had ever known paralleled, even by Liszt himself, whom I personally knew, and in whom passion and delicacy were united. In the circle were musicians who, like me, had heard the greatest pianists in Europe; but we can say that we never heard such truly super-natural executions.3Wisniewski (1894), 86.

Professor J Niclassen, organist and music critic of the Fremdenblatt of Hamburg, described Shepard’s performance in these terms:

Soft, mysterious, sphere like tones, coming and going, fall on our ear … tone-pictures full of poetic charm. Most remarkable is the unfailing surety of touch, in spite of the darkness, especially in octave and wide jumps. Between short pauses, four or five selections followed one another, all completely different in character, giving the widest play to the imagination of the listeners. Suddenly one hears a basso of colossal register, the singer at the same time playing an accompaniment that makes the grand piano quiver … while the mighty basso penetrated to bone and marrow…

[T]he accompaniment becomes more subdued, and to a melodious theme rises a soprano voice of sympathetic quality, which to about the second ‘G’ has a youthful boyish character, but in the highest notes it becomes a decided soprano. A duet is now carried on alternately between a powerful basso and a beautiful soprano, which decidedly belongs to the most extraordinary manifestations in the realm of music.4Campbell Holms (1925), 239.

Matt Marble writes:

He has been lauded by esteemed minds, such as William James and Edmund Wilson, while he befriended significant artists of the period, such as architect Claude Bragdon, composer Arthur Farwell, and writers Alexandre Dumas, Maurice Maeterlinck, Stephane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, and Walt Whitman. Mallarmé once proclaimed that Grierson did “with musical sounds, combinations and melodies what Poe did with the rhythm of the words”; as Maeterlinck announced Grierson to be “the supreme essayist of our age.”

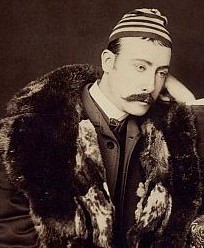

Adding to the mystique of his medial music practice and prophetic writings, Grierson’s appearance over the years offered as much mystery to the onlooker: rouged cheeks, a waxed or orange-dyed mustache, wigs, a ruby ring surrounded by diamonds (and other expensive jewelry given by the royalty he entertained), and a fur coat made of 3,000 squirrel skins. He was known by many notable artists and royal powers as a genius, a madman, or both; but he fascinated the majority he encountered. Dumas had told Grierson during his passage through Paris in the 1860’s, “[w]ith your gifts you will find all doors open before you.”5Marble (nd).

Melvyn Willin

See also: The Illusioned Ear: Disembodied Sound & The Musical Séances of Francis Grierson, an extended biographical appreciation by Matt Marble.

Literature

Blavatsky, H.P. (1875). A word with the singing medium, Mr Jesse Sheppard. Boston Spiritual Scientist 2, July 8.

Campbell Holms, A. (1925). The Facts of Psychic Science and Philosophy. Keegan Paul.

Crane, C. (1987). Jesse Shepard and the spark of genius. Journal of San Diego History, 33/2 & 3.

Fodor, N. (1964). Between Two Worlds: Amazing True Case-Histories of the Occult, the Mysterious, the Marvellous and the Supernatural. West Nyack, New York, USA: Parker.

Gaddis, V.H. (1994). Mystery of the musical medium. Borderlands 50/3.

Grierson, F. (1899). Modern Mysticism and Other Essays. London: George Allen.

Grierson, F. 1901: The Celtic Temperament and Other Essays. London: George Allen.

Grierson, F. (1909). The Valley of Shadows. London: A. Constable.

Grierson, F. (1913). The Invincible Alliance and Other Essays. New York: John Lane.

Grierson, F. (1918). Abraham Lincoln, the Practical Mystic. New York: John Lane.

Marble, M. (nd). The illusioned ear: Disembodied sound and the musical séances of Francis Grierson.

Shepard, J. (1870). How I became a musical medium. Medium and Daybreak Journal (May 6).

Simonson, H.P. (1966). Francis Grierson: A Biographical and Critical Study. New York: Twayne Publishers.

Willin, M. (2005). Music, Witchcraft and the Paranormal. Ely, UK: Melrose Books.

Wisniewski, Prince A. (1894). The Journal of Light (Apr. 28).