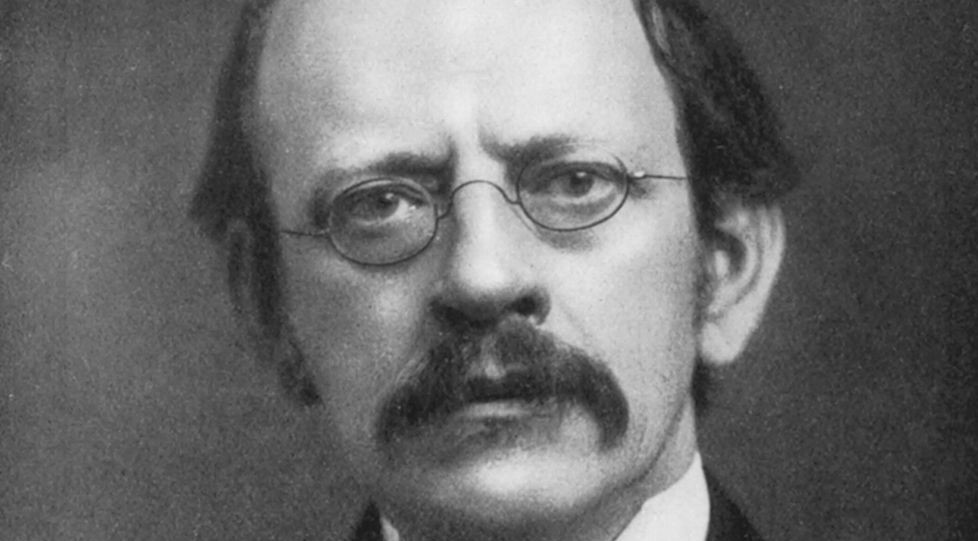

JJ Thompson (1856–1940) was a British physicist who won a Nobel Prize for his discovery of the electron. Thomson had a long-standing interest in paranormal phenomena, notably claims by mediums to produce psychokinetic effects. This article describes his activities and is based on, and condensed from, a published work.1Downard (2021).

Life and Career

Joseph John Thomson was born in Manchester in 1865. He was educated locally at Owens College and then at Trinity College, Cambridge, becoming a Fellow of the college in 1881. In 1884 he was appointed Cavendish Professor of Physics, in preference to older and more experienced candidates. He is best known for detecting two isotopes of neon within cathode ray tubes, a discovery that laid the foundation of the field of mass spectrometry. He was awarded the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of the electron and for his work on the conduction of electricity in gases in the same devices.

Psychical Research

A practising Christian, Thomson was also interested in paranormal phenomena. He joined the newly founded Society for Psychical Research in 1883 and served as a member of its governing council for 57 years from 1883 to 1940, latterly as vice-president. His interest was likely aroused by Balfour Stewart, his physics lecturer at Owens College, who had voiced support for Sir William Crookes at a time when Crookes’s experiments with mediums was causing public controversy, and by Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt), his supervisor at Cambridge, who also showed curiosity in the subject.

During the 1890s Thomson was encouraged by Frederic WH Myers, a cofounder of the SPR and one of its most active investigators, to attend séances by professed mediums offering demonstrations of physical phenomena (slate writing, table levitations, rapping sounds, and the like). In a memoir published in 1936 Thomson stated that he attended ‘a considerable number’ of these, but that the results were ‘very disappointing’ in all but two of them.2Thomson (1936).

One of the mediums was William Eglinton, whose performances included slate writing (a process in which ‘spirits’ were said to write answers to questions posed by sitters on a slate held under the table). Thomson writes:

I went with Myers and Mr H.J. Hood who at the time, took a prominent part in psychical research, to his room, near, I think, to the Marble Arch. Eglinton took a slate which we were allowed to examine, and we found no reason to suspect that it was anything but an ordinary school slate. He then broke a small piece off a slate pencil and placed the fragment on the top of the slate.

We then sat down at a trestle table; he sat at one end, I held his right hand with my left, and with his left hand he held the slate under the table. The piece of slate pencil was between the bottom of the table and the top of the slate. The room was not darkened in any way and all the proceedings took place in broad daylight. He then asked each of us a question which we should like the spirits to answer. Myers and Hood asked questions concerning spiritualism, I preferred a question to which I knew the answer, so I asked what county Manchester was in.

We then sat for, I should think, a quarter of an hour without anything happening. Then he seemed to be seized with convulsions and it was all I could do to hold him up and prevent him from falling off the chair. He recovered in a short time, brought the slate from under the table, and on it was written in a sprawling hand with large illformed letters: Manchester. My view is that Eglinton thought there must be some catch in my very simple question and that he knew that some English towns were counties in themselves and supposed, because I had asked the question, that Manchester was one of them.3Thomson (1936).

The city is in fact mostly in the county of Lancashire. Having caught out Eglinton with his question, Thomson also conveyed how he thought the illusion had been performed; ‘if he had managed to jam the piece of slate pencil in a crevice or depression on the lower part of the table, he might have been able to write without any considerable movement of the arm supporting the slate’.4Thomson (1936).

Thomson’s scepticism with regard to Eglinton was shared by other SPR investigators, notably Eleanor Sidgwick,5Sidgwick (1886). partner of its president, the Cambridge philosopher Henry Sidgwick, and Richard Hodgson, who had earlier exposed fraud by Helena Blavatsky over her claims of physical phenomena.6Hodgson (1886). However, some SPR members, including stage magicians, agreed that there were suspicious circumstances in Eglinton’s performance but doubted that his feats could have been achieved by conjuring.7Lewis (1886).

Thomson was more interested in the case of Eusapia Palladino, an Italian medium whose apparent ability to move objects large and small by means of psychokinesis was being extensively investigated by scientists in many countries. One reported feat involved levitating a table upon which she and others present rested their hands. In others, she reportedly moved objects across a room. Thomson writes:

Eusapia came to Cambridge in the Long Vacation of 1895, and stayed with the Myers. She held some séances and I was present at two of them. At the first, which began about 6 o’clock in the evening, Lord Rayleigh, Professor Richet, Myers, Richard Hodgson, Mrs (Elenanor) Sidgwick, Mrs Verrall and myself were present, along with a few others whose names I have forgotten. We sat at a long table. Eusapia was at one end, Lord Rayleigh on her right, I on her left; and Mrs Verrall was under the table holding her feet …

There was a melon on a small table at some little distance from that at which we sat, and it was part of the programme that the melon should be precipitated onto the table. There were heavy velvet curtains over the windows, and when the lights were all put out it was pitch dark. We formed the circuit by clasping hands in the usual way and sat like this for a considerable time without anything happening. Then Myers, who thought it good policy to encourage mediums at the commencement of a séance, jumped up and said he had been hit in the ribs. The circuit was thus broken and it was perhaps a minute before it was re-formed. Hardly had we got seated when Mrs Verrall called out ‘She’s pulled her foot back’, and then, without an interval, ‘Why, here’s the melon on my head!

He continues:

What had happened was quite obvious: while the circuit had been broken and Eusapia was free she had reached out, got the melon, sat down and put it on her lap, intending to kick it from her knee onto the table. Now if you want to kick from the knee you begin by drawing the foot back. Eusapia had done this, but had been disconcerted by Mrs Verrall calling out, and had not got her kick in in time, and the melon had rolled off her lap onto Mrs Verrall’s head.

Palladino was not amused as Thomson conveys.

Very soon after we had sat down again she began abusing me in a language which I did not understand one word, but Richet, who understood her, said she was accusing me of squeezing her hand and that she would not allow this. Instead of holding her hand, all she would permit was that I might put the tips of my fingers on the back of her hand; this was done. After a short interval she began to abuse Lord Rayleigh, and Richet said she was accusing him of squeezing her hand and that, instead of holding hands, she would put the tips of her fingers on the back of his hand. This change, as was found out later by Mr Hodgson, was the essence of her trick … (Eusapia) would get both hands free, for I should think that I was pressing Eusapia’s hand when as a matter of fact I was pressing Rayleigh’s, and he would think he was still being pressed by Eusapia while in fact he was pressed by me.8Thomson (1936).

Telepathy

Thomson was also interested in a mind-reading act performed in America by Julius and Agnes Zancig, a Danish-born husband and wife team. Julius obtained an object or drawn design from an audience member, which might be a complex geometric shape (Figure 4), and then conveyed the image to his wife. The act was so good as to confound sceptics and convince many scientists that the couple was truly telepathic. Thomson witnessed a private performance in which Rayleigh imposed conditions so stringent, he believed they might have been held to establish the claim. In fact, as Julius revealed before his death, the act was based on a complex code of visual and audible cues.9Anderson (2006).

However, Thomson knew there are ways for two people to communicate beyond sight or audible sounds. Employing his knowledge of physics and music, he relates that the pitch at which a person detects a musical note varies from one person to another. He recalled a boy who came to the Cavendish Laboratory who could detect a whistle not detected by others and was thus deemed inaudible. The power of detecting high notes is much stronger in youth than in old age.

On telepathy in general, Thomson writes:

It is often asserted that telepathy has been conclusively proved. I cannot agree with this for the case of short range telepathy … This does not mean that it has been shown not to exist …

Compared with other branches of psychical research, little has been done on this short range thought transference between living people, though it was this which first suggested the idea. One reason for this is that this power of thought-reading is exceedingly rare, very much rarer than was at first supposed.

Another reason is that attention was at first directed to thought transference between the living and the dead, which raises much deeper and more important questions. In my opinion, the investigation of shortrange thought transference is of the highest importance.

It is quite possible, indeed very probable, that it may turn out to be of an entirely different character from the kind of thought transference that is supposed to occur in dreams or premonitions.10Thomson (1936).

Thomson was said by colleagues in psychical research to be open about his interest in it, and that while he unwilling to commit to a belief in the reality of the phenomena he was by no means ultrasceptical.11Rayleigh (1942).

Thomson also thought that trying to demonstrate paranormal phenomena to scientists was a tall order. He writes:

The people who claim to produce them are very psychic and impressionable, and it may be as unreasonable to expect them to produce their effects when surrounded by men of science armed with delicate instruments, as it would for a poet to be expected to produce a poem while in the presence of a Committee of the British Academy.12Thomson (1936).

Robert McLuhan

Literature

Anderson, R. (2006). Psychics, Sensitives and Somnambules: A Biographical Dictionary with Bibliographies. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Downard, K.M. (2021). Joseph John Thomson investigates the paranormal (historical perspective). European Journal of Mass Spectrometry 27, 151-57.

Hodgson, R. (1885). Report of the committee appointed to investigate phenomena connected with the Theosophical Society. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 3, 201-400.

Lewis, A.J. (1886). How and what to observe in relation to slate-writing phenomena. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 2, 362-75.

Rayleigh, Lord (R.J. Strutt) (1942). The Life of Sir J.J. Thomson, O.M., Sometime Master of Trinity College. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sidgwick, E. (1886). Mr Eglinton. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 2, 282-334.

Thomson, J.J. (1936). Recollections and Reflections. London: G. Bell & Sons.