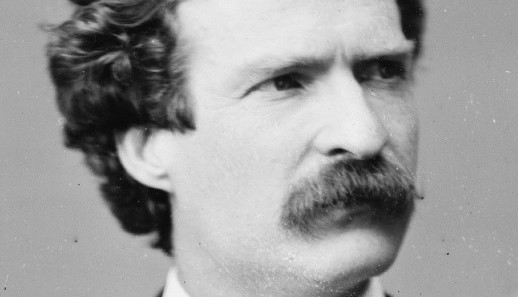

American author Mark Twain (1835–1910) wrote about psychic experiences in his own life, notably telepathic interactions with people at a distance.

Life and Career

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born on 30 November 1835 in Florida, Missouri.1Biographical details from Powers (2005). He adopted the pen name Mark Twain (a nautical term used on Mississippi riverboats). After the death of his father, he left school and became involved in the newspaper industry, initially as a printer’s apprentice and eventually as an editor and reporter. In 1858 he became a steersman on a packet boat on the Mississippi river.

Twain’s first success as a writer came about in 1865 when his humorous story ‘The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County’ was published in the New York weekly The Saturday Press. This brought his writing into public recognition and led to many successful books, lecture tours and an honorary degree from Oxford University. Despite these achievements he was often short of money and prone to fits of despair, notably after the death of his wife and daughter.

His final written work was an autobiography which was published one hundred years after his death.2Twain (2010).

Psychic Experiences

In 1858 Twain experienced what he believed to be a vivid prophetic dream.3Twain (2010), 274-77. He saw his dead brother Henry lying in a metal coffin dressed in one of Twain’s own suits, a bouquet of flowers lying on his chest, a red rose in the centre. A month later, Henry was fatally injured while working on the steamboat Pennsylvania when its boiler exploded. The events that Twain had dreamed of came about, including the details of the metal coffin, the suit and the roses. A recent commentator has judged the incident to be genuinely precognitive, the details being too precise to be attributed to chance or to have been known beforehand.4Charman(2017), 17-25.

Twain became increasingly interested in psychic experiences. He considered the Society for Psychical Research had ‘done our age a very great service’ in its studies of telepathy and wrote to it applying to join in 1884, commenting that ‘[i]n my own case it has often been demonstrated that people can have crystal-clear mental communication with each other over vast distances’.5Twain (1884).

Thought-transference, as you call it, or mental telegraphy as I have been in the habit of calling it, has been a very strong interest with me for the past nine or ten years. I have grown so accustomed to considering that all my powerful impulses come to me from somebody else, that I often feel like a mere amanuensis when I sit down to write a letter under the coercion of a strong impulse: I consider that that other person is supplying the thoughts to me, and that I am merely writing from dictation.6Twain (1884), 166.

In one such incident, at the prompting of his publisher he wrote to William H Wright, a journalist, suggesting that Wright pen a book about the Nevada silver boom, which was making news at the time. But he did not send the letter, having had second thoughts. A week later he received letters in the post, one of which he divined would be from Wright suggesting the exact same scheme, as turned out to be the case when he opened it.7Twain (1891), 98. He wrote articles describing similar coincidences.8Twain (1891), 95-104; Twain (1895), 521-24. See also Horn (1996); Ryan (2019).

In other incidents, he recounted seeing the apparition of a living person9Twain (1895), 521). and of being enveloped by a cold current of air in an otherwise warm room shortly after the death of his daughter, which he took to be an indication of her presence. He stated that similar inexplicable events had happened so ‘frequently in the past nine years, that I could pour them out upon you to utter weariness.’10Twain (1884), 167.

Works

For a detailed catalogue of Twain’s written works see here.

Melvyn Willin

Literature

Charman, R.A. (2017). Re-evaluation of the Samuel Clemens dream precognition case: Did he foresee the future funeral casket of his younger brother Henry? Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 81/1, 166-67.

Horn, J.G. (1996). Mark Twain and William James: Crafting a Free Self. Columbia, Missouri, USA: University of Missouri Press.

Powers, R. (2005). Mark Twain: A Life. New York: Free Press; Jeffereson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Ryan, A.M. (2019). Haunting the ghost of Mark Twain. In The Paranormal and Popular Culture, ed. by D. Caterine & J.W. Morehead. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Twain, M. (1884). Correspondence. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 81/1, 17-25.

Twain, M. (1891). Mental telegraphy. A manuscript with a history. Harper’s Monthly Magazine, December. 95-104.

Twain, M. (1895). Mental telegraphy again. Harper’s Monthly Magazine , September,521-24.

Twain, M. (2010–15). Autobiography of Mark Twain (3 vols.), ed. by H.E. Smith, B. Griffin, & V. Fischer. University of California Press.