Robert Hare (1781–1858), an American chemistry professor and world-renowned inventor, was one of the first scientists to take an active interest in psychical research. His 1855 book Experimental Investigation of the Spirit Manifestations describes experiments with mediums, from which he derived the conviction of having communicated with deceased friends and family members.

Contents

Life and Career

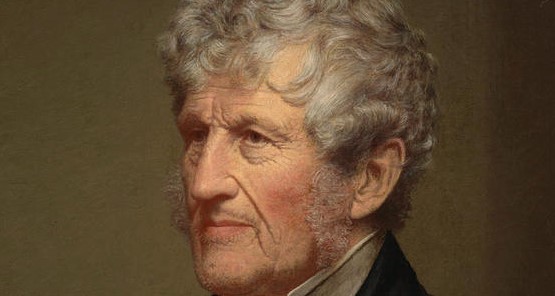

Robert Hare was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 17 January 1781, the son of a prominent Philadelphia brewery owner who also served as a state senator. He was educated at home and tutored in chemistry by Dr James Woodhouse, founder of the Chemical Society of Philadelphia. He gained international fame in 1801 (when only 20 years old) for his invention of the oxyhydrogen blowpipe, a forerunner of the modern welding torch. He was the first person to fuse lime, magnesia, iridium and platinum, and, in 1816, invented the calorimotor, a type of battery from which heat is produced. This led to his invention of the deflagrator, which was employed in volatilizing and fusing carbon. He became the first recipient of the Rumford Medal for the invention of the oxyhydrogen blowpipe and his improvement in galvanic methods.1Sketch of Robert Hare (1893).

Hare was awarded honorary MD degrees from Yale University in 1806 and from Harvard University in 1816. In 1818, he was appointed professor of chemistry and natural philosophy at William and Mary College and that same year was made professor of chemistry in the department of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, where he remained until his retirement in 1847. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

Hare wrote more than 150 papers for scientific publications and frequently wrote on other subjects, including politics, economics, and philosophy, under the pen name ‘Eldred Grayson’. In an 1810 article, Brief View of the Policy and Resources of the United States, Hare advanced the idea that credit is money. He also wrote frequently in opposition of slavery.

Investigation of Mediums

In a letter of 27 July 1853, published (some days later) by the Philadelphia Inquirer, Hare stated that he felt it his duty to bring whatever influence he possessed to stem the tide of the ‘popular madness’ and ‘gross delusion’ called spiritualism.‘I recommend to your attention, and that of others interested in this hallucination, Faraday’s observations and experiments, recently published in some of our respected newspaper,’ he concluded the letter, referring to the phenomenon of table turning (tables being levitated and spelling out messages), adding,‘I entirely concur in the conclusions of that distinguished experimental expounder of Nature’s riddles.’2Hare (1855), 36.

Several months later, Hare heard from one Amasa Holcombe taking issue with his letter. Holcombe informed him that he had observed various phenomena over the preceding three years and was certain that Faraday’s explanation, which called for muscular force, was wrong. He challenged Hare to witness similar phenomena before condemning it. Hare accepted the challenge and began his investigation, sitting with mediums over the next fourteen months. Initially, communications came by way of raps and table tilting. ‘I learned that simple queries were answered by means of these manifestations,’ he wrote, ‘one tap being considered as equivalent to a negative; two, to doubtful, and three, to an affirmative. With the greatest apparent sincerity, questions were put and answers taken and recorded, as if all concerned considered them as coming from a rational though invisible agent.’3Hare (1855), 38.

Messages were also communicated by means of sitters reciting the alphabet and waiting for a rap or a tilt of the table to indicate the required letter. Hare was mystified, but after carefully surveying the situation felt that that there was no possibility of conjuring tricks or deception. However, he observed that the process was very slow, and contrived an apparatus, which he called a ‘spiritoscope’, to expedite communication. This machine consisted of a circular disk surrounded by the letters of the alphabet, attached to the tilting table by weights, pulleys and cords. The medium sat behind the table in order to supply the ‘psychic force’ through which the spirits caused the table to tilt or raps to me made, but the medium could not see the wheel and had no idea what was being spelled out.

Put to the test, the contraption worked and the first spirit to communicate was Hare’s deceased father, Robert Sr.When Hare continued to doubt, the communicator responded, ‘Oh, my son, listen to reason!’4Hare (1855), 41. At a second sitting, the same individual again communicated, saying that his deceased mother and sister also were there, but not his brother (who was living).Personal information was given to Hare, of a kind which Hare was certain the medium could not have researched.

In a third sitting in which the machine was used, a message was spelled out that his sister was there. As a test question, Hare asked her to name their father’s partner in his business venture. ‘The disk revolved successively to letters correctly indicating the name to be Warren,’ Hare recorded. He then asked his sister the name of their English grandfather, who had died in London more than seventy years earlier. The correct name was again given. ‘The medium and all present were strangers to my family, and I had never heard either name mentioned except by my father,’ Hare further recorded.5Hare (1855), 44-45.

With another medium, who Hare was certain knew nothing of his family, he asked for the name of an English cousin who had married an admiral; the machine correctly spelled out the name. Hare then asked for the maiden name of an English brother’s wife; the machine spelled ‘Clargess,’ which also was correct.6Hare (1855), 45.

Hare said he also witnessed table levitations.‘It was at the same mansion … that I first saw a table continue in motion when every person had withdrawn to about a distance of a foot; so that no one touched it; and while thus agitated on our host saying, “Move the table toward Dr. Hare,” it moved toward me and back again.’ He then observed the table ‘violently overset’ and while upside down continue to vibrate while a young girl, about 12 years of age, held a single finger on it.7Hare (1855), 46.

Subconscious Mind

At a sitting with a Mrs Hayden, Hare received a message from a spirit identifying himself as CH Hare. Not immediately recognizing the communicator by his initials, Hare asked if he might be the son of his cousin, Charles Hare, of St Johns, New Brunswick. ‘Yes,’ was then spelled out. ‘This spirit then gave me the profession of my grandfather, also that of his father, and the fact of the former having been blown into the water at Toulon, and of the latter having made a miraculous escape from Verdun, where he had been confined until his knowledge of French enabled him to escape by personating in disguise an officer of the customs,’ Hare wrote.8Hare (1855), 53. Hare was unaware of the young man’s death, but later learned that he had been killed at sea in a shipwreck. This contradicted the theory, which was current even at this early stage, that the subconscious mind of the sitter was somehow providing the information to the medium. ‘The employment of letters to express ideas neither existing in the mind of the medium nor in mine, cannot evidently be explained by any psychological subterfuge,’ Hare wrote.9Hare (1855), 52-53.

At some point Hare appears to have developed mediumistic abilities of his own, as was suggested by a communication taking place on 3 July, 1855 at the Atlantic Hotel on Cape May Island.Hare recorded that at 1 am, a time when he knew that his friend Mrs M. B. Gourlay was conducting a séance in Philadelphia, he asked his deceased sister to go toher and request her to induce Dr Gourlay, her husband, to go to the Philadelphia Bank to ascertain at what time a certain note would be due, and that he (Hare) would sit at his instrument at 3.30 pm that day to receive the answer. ‘Accordingly, at that time, my sister manifested herself and gave me the result of the inquiry.On my return to the city, I learned from Mrs Gourlay that my angelic messenger had interrupted a communication, which was taking place through the spiritoscope, in order to communicate my message, and, in consequence, her husband and brother went to the bank, and made the inquiry, of which the result was that communicated to me at half-past three o’clock by my sister.’10Hare (1855), 33, 54.

Here again, Hare wondered how this could be accounted for by the theory holding that the subconscious is responsible for all mediumistic phenomena.‘Why is it necessary that the index over a disk at Cape May, should revolve to the letters requisite to spell a message, in order that the index of another disk in Philadelphia, should revolve at a subsequent time?’ he pondered. ‘How does the mechanism in one place acquire a power from the remote situation of another?’11Hare (1855), 172.

Purpose of Manifestations and Communication

Hare asked the communicator who identified himself as his father the purpose of the manifestations and communications that he had been experiencing. He was informed that it was ‘a deliberate effort on the part of the inhabitants of the higher spheres to break through the partition which has interfered with the attainment, by mortals, of a correct idea of their destiny after death.’12Hare (1855), 85. To carry out this intention, he was told, a delegation of advanced spirits has been appointed. He was further informed that lower spirits were allowed to take part in the undertaking because they were better able to make mechanical movements and loud rappings than those on the higher realms.

Hare asked why it all began in Hydeville, near Rochester (New York), referring to the rappings first heard by the Fox sisters of that village in 1848 (an event widely cited as the beginning of the spiritualism phenomena). ‘The answer to this was that the spirit of a murdered man would excite more interest, and that a neighbourhood was chosen where spiritual agency would be more readily credited than in more learned or fashionable circles, where the prejudice against supernatural agencies is extremely strong,’ Hare related, adding that he was also told that attempts had been made by spirits elsewhere but without success.13Hare (1855), 85.

Hare’s father explained the difficulties in communicating:

As there are no words in the human language in which spiritual ideas may be embodied so as to convey their literal and exact signification, we are obliged oftimes to have recourse to the use of analogisms and metaphorical modes of expression.In our communication with you we have to comply with the peculiar structure and rules of your language; but the genius of our language is such that we can impart more ideas to each other in a single word than you can possibly convey in a hundred.14Hare (1855), 96.

The communicators also told Hare that there were degrees of gradation between those of vice, ignorance, and folly and those of virtue, learning, and wisdom. One’s initial place in the afterlife environment, he was told, is based on a sort of ‘moral specific gravity’. Moreover, he was informed that spirits cannot effectively approach a medium who is much above or much below their particular level.

As media, in proportion as they are capable of serving for the higher intellectual communication, are less capable of serving for mechanical demonstrations, and as they are more capable of the latter are less competent for the former, likewise have a higher or lower capacity to employ media. It has been mentioned that having made a test apparatus, my spirit sister alleged that it could not be actuated by her without assistance of spirits from a lower sphere.15Hare (1855), 160.

Negative Reaction

After declaring his belief in spirits during 1854, Hare came under attack by his scientific colleagues, one former admirer denouncing his conversion to spiritualism as ‘insane adherence to the gigantic humbug’.16Hardinge (1869), 119. Having praised him for his scientific work, the Philadelphia Ledger concluded his obituary by stating that due to a ‘worn and wearied mind’ Hare suffered from delusions in his old age, believing that it was possible to communicate with the dead.

Final Beliefs

But Hare remained steadfast in his new worldview until the end of his life. ‘It is a well-known saying that there is “but one step between the sublime and the ridiculous,” ’ he explained. ‘If I am a victim to an intellectual epidemic, my mental constitution did not yield at once to the miasma.’17Hare (1855), 15.

Hare concluded his book by stating: ‘No evidence of any important truth in science can be shown to be more unexceptionable than that which I have received of this glorious fact, that heaven is really “at hand,” and that our relatives, friends, and acquaintances who are worthy of happiness, while describing themselves as ineffably happy, are still progressing to higher felicity; and while hovering aloft in our midst, are taking interest in our welfare with an augmented zeal or affection, so that, by these means, they may be a solace to us, in despite of death.’18Hare (1855), 428.

Michael Tymn

Literature

Robert Hare Papers 1764-1858 (n.d.) American Philosophical Society.

Berger, A.S., & Berger, J. (1991) The Encyclopedia of Parapsychology and Psychical Research. New York: Paragon House.

Doyle, A.C. (1926) The History of Spiritualism. New York: George H. Doran Co.

Fodor, N. (1966). Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science. New York: University Books.

Hardinge, E. (1869/1970). Modern American Spiritualism. New York: University Books.

Hare, R. (1855). Experimental Investigation of the Spirit Manifestations. New York: Partridge & Brittan.

Sketch of Robert Hare (1893). Popular Science Monthly 42, March.

Tymn, M. (2011). The Afterlife Explorers, White Crow Books, UK.