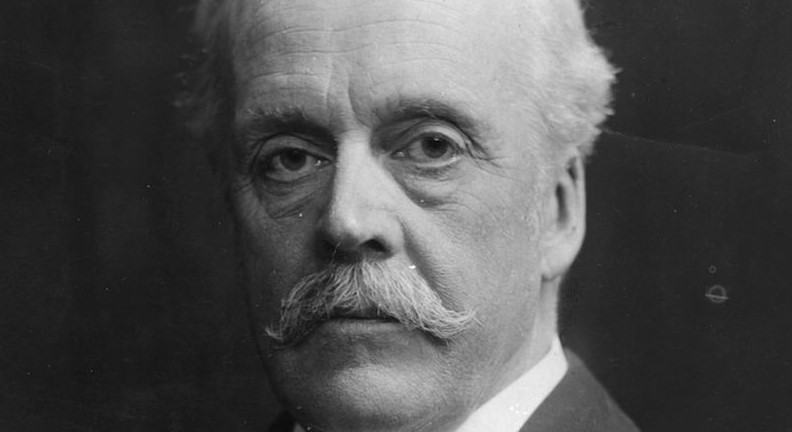

Arthur Balfour (1848–1930) was a Tory politician and philosopher, with an interest in psychical research. He is associated in particular with the Palm Sunday case, a notable episode in the mediumship research known as the Cross-Correspondences. He served as president of the Society for Psychical Research from 1892 to 1894.

Contents

Life and Career

Arthur James Balfour was born on 25 July 1848 in East Lothian, Scotland. He was descended from the Cecil family, prominent in the Tudor period; his godfather was the Duke of Wellington. He was educated at Eton College and read moral sciences at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Balfour became prominent in Tory politics and held several senior ministerial positions. He was prime minister from 1902 to 1905, and was later foreign secretary. He was made a peer in 1922, becoming Earl of Balfour.

Balfour also wrote philosophical works, arguing in books such as A Defence of Philosophic Doubt (1879) that religious belief could be soundly based on scientific principles. He held numerous academic positions, including president of British Association for the Advancement of Science (1904), president of the British Academy (1921), and chancellor of Cambridge University (1919).

Psychical Research

Balfour joined the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in 1882 and served as its president in 1892-4. He was fascinated by psychical matters, especially evidence for telepathy, but his political career allowed little time to pursue this.

Palm Sunday Case

Balfour is known in psychical research principally for his involvement in a mediumship case concerning a deceased female friend, Mary Lyttelton, with whom he had been romantically involved. Lyttelton died of typhus fever on Palm Sunday 1875, before he was able to propose to her, to his lifelong regret. On a visit shortly before his death in 1930, Winifred Coombe-Tennant a medium known at the time by the pseudonym ‘Mrs Willett’, said she psychically perceived a young woman watching over him. Subsequently other mediums, including Margaret Verrall, Helen Salter and ‘Mrs Holland’, wrote automatic (trance) scripts which it was believed were dictated by this woman. The scripts contained references to:

- Palm Maiden (she died on Palm Sunday)

- Lady with the candle (as she was depicted in a photograph)

- May blossom (she was commonly called ‘May’ and was born in May)

- Cockleshells (depicted in to the Lyttelton family heraldic arms)

- The nursery rhyme ‘Mary, Mary quite contrary’ (which includes her name and ‘cockleshells’)

Symbolic words and statements indicated that the messages were intended for Arthur Balfour. The references were scrutinized by Balfour’s brother Gerald Balfour, who had become involved in psychical research, together with JG Piddington, Alice Johnson, Oliver Lodge and Eleanor Sidgwick – all of them experts in analysis of the so-called Cross-correspondences, of which this appeared to be a prime example.1Balfour (1960), 99-103.Arthur Balfour himself was eventually persuaded that the communications came from the surviving spirit of Mary Lyttelton.

A 1960 analysis by Jean Balfour, a relation by marriage, concluded that

even if some of the material of the scripts arose from ideas in the automatists’ own minds or from thought-transference between them, the source of the symbolism in relation to this case is far from likely to have emanated from their individual subliminal selves. The scripts do really seem to build up in support of the claim made by the ostensible communicators that they were the work of a group in the Other World operating through a mediumistic group with the intention to obtain the scrutiny and understanding of yet another living group. Nothing like this has ever appeared before in the history of psychic occurrences.2Balfour (1960), 247.

Works

Selected Books by Balfour

A Defence of Philosophic Doubt (1879). London: Macmillan & Co.

Decadence: The Henry Sidgwick Memorial Lecture (1908). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Arthur James Balfour as Philosopher and Thinker: A Collection of the More Important and Interesting Passages in His Non-Political Writings, Speeches, and Addresses, 1879-1912 (1912, with W.M. Short). London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Theism and Humanism (1915). New York: Hodder & Stoughton.

The Letters of Arthur Balfour and Lady Elcho 1885-1917 (1992, with M.C. Wyndham), ed. by J. Ridley and C. Percy. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Selected Articles by Balfour

Some remarks on Professor Richet’s experiments on the possibility of clairvoyant perception of drawings (1888). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 3, 348-54.

Reflections on the scientific investigation of hypnotic mental states (1894). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 6, 190-93.

Presidential Address (1894). Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 10, 1-13.

Selected books and articles about Balfour

Rasor, E.L. (1998). Arthur James Balfour, 1848-1930: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press.

Raymond, E.T. (1920). A Life of Arthur James Balfour. Wisconsin, USA: Little, Brown.

Dugdale, B. (1936). Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS. Vols. I & II. London: Hutchinson.

Young, K. (1963). Arthur James Balfour: The Happy Life of the Politician, Prime Minister, Statesman and Philosopher – 1848-1930. London: G. Bell and Sons.

Egremont, M. (1980). A Life of Arthur James Balfour. London: William Collins and Company Ltd.

Melvyn Willin

Literature

Balfour, A. (1894). Presidential address. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 10, 1-13.

Balfour, J. (1960). The ‘Palm Sunday’ Case. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 52, 79-267.

Haynes, R. (1982). The Society for Psychical Research 1882-1982: A History. London: MacDonald & Co.