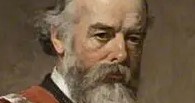

Sir Oliver Lodge (1851–1940) was a physicist noted for his work in electricity, thermo-electricity, and thermal-conductivity. He was an active investigator of mediums in the early years of the Society for Psychical Research, during the course of which he became convinced of the reality of survival of death.

Early Life

Lodge was born in Penkhull, Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, the eldest son of Oliver Lodge and Grace née Heath. His grandfathers were clergymen and schoolmasters; both died before he was born. He was educated at Newport Grammar School in Shropshire and worked briefly in his father’s potteries business before gaining a science degree from University College, London in 1875, and a doctorate in science from the same institution in 1877.

Lodge married Mary Fanny Alexander Marshall, an artist, in 1877. He taught mathematics and chemistry at Bedford College in London while lecturing at University College, London, until his appointment in 1881 as professor of physics and mathematics at University College, Liverpool. Lodge became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1887. He perfected a radio wave detector known as a ‘coherer’ and was the first person to transmit a radio signal, a year before Marconi. He later developed the electric spark plug.

In 1900, Lodge was appointed principal of Birmingham University, remaining there until his retirement in 1919. He was awarded the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society in 1898 for his researches in radiation, was knighted in 1902 for his contributions to science, and in 1919 received the Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts as a pioneer in wireless telegraphy. He served as president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1913.

Lodge authored many papers and books on science, the latter including Man and the Universe (1908), Life and Matter (1912), Ether and Reality (1925), Relativity (1926), Evolution and Creation (1926), Science and Human Progress (1927), and Modern Scientific Ideas (1927).

He served as president for the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) from 1901 to 1903 and again in 1932.

Interest in Psychical Research

While living in London during the 1870s he met Edmund Gurney, later a co-founder of the SPR. At this time he considered Gurney’s interest in the paranormal ‘strange’ and took no interest in the subject. He wrote:

It did not seem to me possible that man could survive the death of the body. I did not think we could ever know the truth about things of that kind, and was content with whatever destiny lay in store for us, without either inquisitiveness or rebellion. I felt that our knowledge would not make any difference, and that we had better leave questions of that kind to settle themselves in due course.1Lodge (1932), 345.

Around 1883, Lodge witnessed an impressive demonstration of ‘thought-transference’, later called telepathy, by a stage performer named Irving Bishop. He then began to wonder if a dislocation might exist between mind and body, rather than the two being inseparably connected, as his education had led him to believe. His curiosity on this matter prompted him to join the SPR, where he again met Gurney and was introduced, in 1884, to Frederic WH Myers, another co-founder of the SPR, becoming a close friend.

During the winter of 1889, Lodge and Myers closely studied Leonora Piper, an American medium who had been invited to England by the SPR following favorable reports about her from its American branch in Boston. Over several months, Lodge held eighty-three sittings with her. On one early occasion, he invited Gerald Rendall, principal of University College, Liverpool, introducing him to Piper as ‘Mr Roberts’. After she was entranced, Piper’s ‘spirit control’ – viewed by some as a discarnate medium on the other side and by others as an alter ego or secondary personality – correctly gave the names of Rendall’s brothers along with specific details about them. Rendall handed Piper a locket, which stimulated reminiscences relevant to the deceased friend to whom it had belonged. There were some incorrect statements, but Rendall was satisfied that the correct statements could not have been achieved either by chance guessing or by ‘fishing’ for information.

Another sitter was Professor ECK Gonner, an economics lecturer. To test the possibility that Piper might have researched the backgrounds of people she believed might be presented to her for sittings, Lodge introduced him as ‘Mr McCunn’, the name of a different colleague. However, Piper gave detailed and correct information relating to Gonner. Among other things, she described how Gonner’s Uncle William was killed ‘with a hole in his head, like a shot hole, yet not a shot, more like a blow,2Lodge (1909), 216. an accurate reference to his death from being struck in the head by a stone during an election riot.

Convinced by now that Piper was not a charlatan, Lodge nevertheless sympathized with the theory favored by American investigators of Piper, notably William James and Richard Hodgson, that a ‘secondary personality’ in Piper’s subconscious received the information telepathically from living people, or conceivably from some ‘cosmic reservoir’ of facts and memories. However, as the investigation of Piper progressed, Lodge became convinced that the appearance of deceased spirits communicating their memories to the living was the true explanation, accepting that human personality and consciousness survive the death of the body.

The proof that the discarnate intelligences retained their individuality, their memory, and their affection, forced itself upon me, as it had done upon many others. So my eyes began to open to the fact that there really was a spiritual world, as well as a material world which hitherto had seemed all sufficient, that the things which appealed to the sense were by no means the whole of existence.3Lodge (1932), 346.

Lodge made these views public in a 1909 book, The Survival of Man.

During summer of 1894, Lodge joined an investigation of the Italian physical medium Eusapia Palladino in the company of Charles Richet, a professor of medicine and physiology at the University of Paris, Julian Ochorowicz, a Polish psychologist, and Myers, at Richet’s private retreat on Ribaud Island in the Mediterranean. The four men witnessed phenomena they believed was supernormal: ghostly faces and hands; furniture some distance from the medium being moved and levitated; and objects first floating freely, then set down on the table by invisible hands. The evidence was somewhat weakened by the low level of light, and Palladino’s tendency to cheat – whether unconsciously in the trance condition or consciously – when not properly controlled. Lodge considered the effects less interesting than the mental phenomena he had observed with Piper, and commented on their superficial likeness to conjuring tricks, but added: ‘the variety is very great, and the evidence for the activity of supernormal intelligences in controlling them is decidedly strong’.4Lodge (1932), 310-11.

Later sittings with Gladys Osborne Leonard, a British trance medium, resulted in communications that seemed to come from his son Raymond, an army officer who had recently been killed in battle. The sittings, held by Lodge, his wife and some of Raymond’s siblings, were described in his bestselling 1916 book, Raymond or Life And Death. (See Raymond)

Lodge authored several other books dealing with spirituality and philosophy, including Science and Religion (1914), Raymond Revised (1922), Why I believe in Personal Immortality (1928), Phantom Walls (1929), The Reality of a Spiritual World (1930) and My Philosophy (1933).

Michael Tymn

Literature

Berger, A.S., & Berger, J. (1991). The Encyclopedia of Parapsychology and Psychical Research. Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA: Paragon House.

Cook, W. (1917). Reflections on “Raymond”: An Appreciation and Analysis. London: Grant Richards Ltd.

Gauld, A. (1968). The Founders of Psychical Research. New York: Schocken Books.

Holt, H. (1914). On the Cosmic Relations. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. (Includes many citations from the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research.)

Hyslop, J. (1918). Life After Death. New York: Dutton.

Lodge, O. (1909). The Survival of Man. New York: Moffat, Yard and Co.

Lodge, O. (1916).Raymond or Life and Death. New York: George H. Doran.

Lodge, O. (1929). Phantom Walls. UK: Hodder and Stoughton, Ltd.

Lodge, O. (1932). Past Years. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Mercier, C.A. (1917/2012). Spiritualism and Sir Oliver Lodge. London: Forgotten Books.

Tweedale, C.L. (1909). Man’s Survival After Death. London: The Psychic Book Club.

Tymn, M. (2013). Resurrecting Leonora Piper: How Science Discovered the Afterlife. Guildford, UK: White Crow Books.