Eusapia Palladino (1854–1918) was an Italian séance medium who was reputed to produce ‘physical’ phenomena such as rappings, table elevations, movements of objects and ectoplasmic materializations. The phenomena were said to be of such striking strength, variety and reliability that she attracted the attention of scientists throughout Europe, becoming one of the most intensively studied mediums of all time. The research literature on Palladino is extensive. Many credible investigators were convinced of the genuineness of the effects, which were often visible in good light. However, her somewhat uncouth manners and blatant tendency to cheat when given the opportunity made her a controversial figure, and she remains the subject of dispute.

Contents

Biography

Eusapia Palladino was born in Southern Italy, in Minervino Murge, part of Bari. Her birth certificate and other census information shows that her name was Eusapia Maria, that she was born on 20 January 1854, and that her father and mother were farmer Michele Palladino and Irene Barbiere. It is also stated that she had two husbands, whom she married in 1885 and in 1907.1Anon (1918b).

Accounts of Palladino’s early life are problematic owing to a lack of early biographical details.2Such as those presented by Carrington (1909), de Rochas (1896) and Lombroso (1909). The available information is based on her own accounts, which, however, are marred by what has been described as her ‘curious vice of recounting the facts of her life in different ways to various persons who asked her about it’.3Biondi (1988), 96-97; this and other translations by C. Alvarado. Many stories about her early life should be taken with a grain of salt.4Alvarado (2011). But most accounts concur about a hard and unhappy childhood as an orphan. She stated:

My mother died soon after my birth. I … was placed by my father in charge of a family who had a farm … When I was still very small I was put to work at many little occupations about the farmhouse. I had no play like most children, no companions; it was work always. Before I was ten years old my father was killed by brigands … The people with whom I lived did not care for me. I had never known love … 5Palladino (1910), 294–95.

She said a friend of her father took her to a family in Naples who wanted to adopt and educate her. She escaped and tried unsuccessfully to return to her father’s friend. In due course she found another family who wanted her to become a nun, which she resisted. She wrote:

I could never obey fixed laws. My own will guides me. It is enough. If I suffer from it, very well; it is my own suffering … I had no patience; I could not rest. Often I would grow excited without cause. Suddenly I would weep. When I went to sleep at night I would have strange dreams. I have always had them, and sometimes when bad luck is coming I dream of serpents.6Palladino (1910), 296.

Called into a room one day, Palladino stated, she found people sitting round a table with their hands on it, and was asked to join them. Soon after this the table started to move.

I began to have a half dizzy feeling, a swimming of the head. My arms and body seemed to stiffen and shake, as if from a bursting force pushing for release. It was almost pain at first. But relief came … I breathed easily again, and looked up at the others, who had risen and were speaking eagerly … 7Palladino (1910), 297.

The table had raised from the floor and objects in the vicinity had moved, she was told. This event led to other séances and the beginning of her reputation as a medium.

Others referred to manifestations during Palladino’s youth such as waking hallucinations, ‘expressive eyes watching from behind a pile of stones or a tree, always to the right’.8de Rochas (1896), 15.She was also said to hear raps suddenly coming from pieces of furniture on which she happened to be leaning, having her clothes or bed-covers stripped from her in the night, and seeing ghosts or apparitions.9Lombroso (1909), 39-40.

Between 1872 and 1886, she took part in séances held with friends.10According to Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 123. Early in her career as a medium Palladino was influenced by Italian spiritists Giovanni Damiani and Ercole Chiaia: according to Massimo Biondi, a historian of Italian psychical research, Damiani acted as her advisor while Chiaia became her manager.11Biondi (1988), 96, 124. In 1872, the London publication Spiritual Magazine printed a letter from Damiani about Palladino:

We have here in Naples a medium of extraordinary and varied powers. Her name is Sapia Padalino [sic], a poor girl of sixteen, without parents or friends. She is a medium for almost every kind of spiritual telegraphy known, one of which however is peculiarly her own, and consists in writing with her finger, and leaving behind marks as of a lead pencil, while no such article is in her possession or even in the room. She will also take hold of the hand of the sitters, and cause the same phenomenon of leaving traces as of lead pencil under their fingers. In her presence discharges are heard as from pistols; lights are seen across the room like the tail of a comet. She is a seer, a clairaudient, and an impressional medium.12Anon. (1872), 287.

As a woman of around thirty, Chaia wrote, various physical phenomena were seen to take place in her presence, including items of furniture lifting into the air and descending in ‘waves’ or in ‘spirals’, apparently the effect of an intelligent will.13Chiaia (1889), 124.

She was widely described as belonging to ‘the most humble class of society’,14de Rochas (1896), 3.and by all accounts was uneducated and illiterate. According to Enrico Morselli, an Italian scientist and one of her earliest investigators, ‘she barely writes her own name, and is not able to talk in other languages but a mixed dialect of Apulian and Napolitan’.15Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 124. Nonetheless, she was also said to be shrewd and highly aware of the intentions of others.

This description of her is given by Julian Ochorowicz, a Polish researcher who travelled to Rome in 1893 to carry out an investigation:

A small, corpulent but quite shapely figure rushed in, wearing a rakish hat, out of breath, cheerful, and greeted her acquaintances. She related, in her Neapolitan Italian, that, being scatterbrained, she missed the morning train and has only just arrived. … Eusapia is no longer young, nor is she pretty, yet with her liveliness and pleasing facial features she gives the impression of a likable rascal. The large black eyes flash and sparkle when she livens up, while the hands gesticulate in the lively manner of a southerner. In moments of excitement she is very funny: She grabs her neighbours by their lapels, bounces up and down, and at the mention of Torelli [a hostile sceptic] she shakes with anger. At the same time she betrays more sensitive emotions and gets easily moved when wrong is done to others.16 Ochorowicz (1913/2018), 87.

Palladino was said often to receive gifts of jewellery and was known to like gold.17Lombroso (1907), 393. Like many other mediums she was paid for her work, but she did not seem to accumulate money. By her own account she was poor, lived in a small room, and at one stage owned a small shop.18Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 124.

For much of her career as a medium she was sought after by investigators, peaking with a series of séances in New York in 1909–1910. Thereafter her activity diminished, although there are records of séances also after that date, particularly in Italy.19Alvarado (1982). Palladino died in 1918, according to one account of nephritis.20Miranda (1918), 142. Her death was noted outside Italy, with obituaries carried by The Times and the New York Times.21Anon. (1918a, 1918c).

Phenomena

Enrico Morselli presented a detailed classification of the phenomena observed with Palladino.22Morselli (1907), 342-59. Following the custom established by researchers, he divided it into subjective (mental) and objective (physical) occurrences. The mental included, among others, trances, changes of personality (to that of her ‘spirit control’ John King), suggestibility, communications in other languages, and apparent instances of veridical knowledge (true information gained paranormally). The majority were of the physical type, among them

- movement of objects, with and without contact from the medium

- changes in the weight of objects (including her own body)

- cold breezes

- raps, voices and other sounds

- writing, plaster impressions and other permanent effects

- luminous manifestations, as points of light and clouds

- materializations, including disembodied hands, indefinite forms and full forms

Trance

Most of Palladino’s effects occurred while she was in what observers referred to as a state of trance (a phenomenon which, however, was not clearly measured or understood). In the trance state she often talked as if her organism was taken over, or ‘controlled’, by the personality calling himself John King, who was said give her advice.23de Rochas (1896), 16.

Changes in her body were associated with the trance. Cesare Lombroso stated that ‘all the secretions — sweat, tears, even the menstrual secretions — are increased’, and that she also showed hyperesthesia and muscular weakness. He added that her breathing rate diminished, her heart rate increased, her hands showed tremors, she turned pale, and that she entered a ‘state of ecstasy … exhibiting many of the gestures that are frequent in hysterical fits, such as yawnings, spasmodic laughter, [and] frequent chewing … ’

Another student of Palladino’s mediumship saw her trances as being similar to the somnambulistic (hypnotic) state in which she was highly suggestible. This, in his view, led to an increase in motor and sensory processes.24Arullani (1907), 27.

Lombroso classified the medium’s trances in various stages, and believed that the more important phenomena, such as materializations, correlated with the deeper stages. Morselli was less convinced of an ‘absolute correspondence with the depth or the phase of her trance state’.25Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 209. Palladino also produced phenomena in her normal waking state, although this tended to be of low magnitude.26e.g., de Rochas (1896), 310-14.

Movement of Objects

This was probably the most frequent of the phenomena observed.

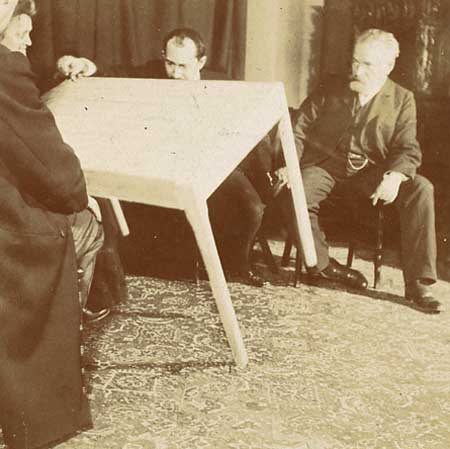

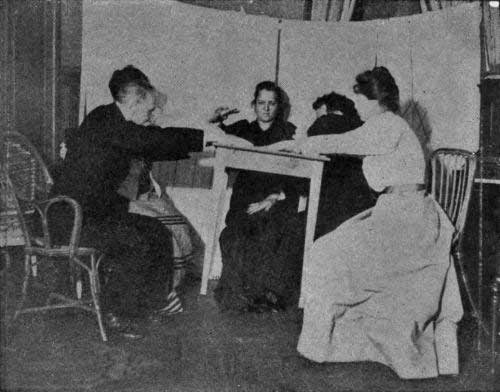

In many séances a ‘cabinet’ was used (traditionally of wooden construction, but in the case of Palladino generally a corner of the room separated by a curtain). Objects such as musical instruments were placed on a table behind the curtain, with the purpose of seeing whether the medium might influence them to move or play at a distance.

The medium sat on a table outside with her back to the curtain, but close to it, while the other participants sat around the table. In one séance:

The table on which the toys had been placed, and which we will call No. 1, made a noise in the interior of the cabinet, from which it at last came out completely. Then there began to arrive on the séance table many objects from table No. 1: a sheet of paper, a little wooden sheep, and a mandolin; the latter was accompanied by the curtain which covered the handle; the curtain, being pushed back by M. Foà, came back and covered the handle of the mandolin … 27Aggazzotti e al. (1907), 367-68.

Table levitations were frequent, as in the following example:

We obtained a levitation lasting about 10 seconds at a height of 30–40 cm and a shorter but higher one while Palladino was the only one standing up. Finally, at the end of the session, an additional levitation occurred that lasted several seconds while all of us were standing up at Palladino’s request …Sometimes we tried all together to lower it by pressing its surface with our hands, but without success. It yielded and lowered a little but as soon as we let go our hands it rose up again.28Bottazzi (1909/2011), 89.

Effects sometimes continued even after the séance had been brought to a close. In one instance reported by Lombroso, soon after the lights had been turned on

a great wardrobe that stood in the alcove room, about six and a half feet away from us, was seen advancing slowly toward us. It seemed like a huge pachyderm that was proceeding in leisurely fashion to attack us, and looked as if pushed forward by someone.29Lombroso (1909), 58.

The medium was once asked to affect a postal scale while several observers focused on her and on the scale. According to de Rochas she first placed one hand a few inches above the plate, but this did not affect the instrument. Then she placed her hands on either side of the plate at a distance of three or four centimeters, and made up and down movements:

Initially, the tray was stationary; soon it oscillated repeatedly up and down synchronously with the hands. At last, Eusapia having lowered her hands, the tray was lowered completely … During this time the medium did not move anything but her hands, the table, firmly placed, did not suffer any kind of disturbance.30de Rochas (1896), 311-12.

The experiment was successfully repeated.

Sometimes the object affected was the medium herself. On one occasion a sitter asked if she could be raised over the table. ‘Eusapia was raised above the table, 10 to 15 centimeters; each of us could freely pass our hands under the feet of the magician suspended in the air!’31Chiaia (1890), 327.He further wrote: ‘I had the opportunity to witness a most extraordinary thing again; one evening I saw the rigid extended medium, in the most complete state of catalepsy, in a horizontal position, with only the head supported by the edge of the table, for five minutes, in the light of the gas … ’32Chiaia (1890), 327.

Breezes

Some of the breezes reported in the medium’s presence appeared to come from a scar on her forehead. Hereward Carrington wrote:

I examined the famous scar, both with my fingers and optically, and held my hand at a distance of about three inches from her head. The cold breeze was distinctly perceptible. We all felt this in turn, holding Eusapia’s mouth and nose, so that she could not breathe. We held our own breaths, and again placed our hands over the famous scar. We felt the breeze as distinctly as ever—it being considerably colder than the temperature of the room.33Carrington (1909), 198.

Luminous Effects

The following observation was recorded early in the medium’s career:

Soon we saw emanate from the body of Eusapia, a number of small bluish flames that sprang up in the air in various directions; some, getting very high were separated into three or four smaller ones.34Chiaia (1890), 327.

A later observation started with a light appearing about the medium’s head, similar to that made by a pocket lamp.

A few moments later, the bright light, well localized, reappeared; immediately afterwards the toy piano, which was on the table all the time with the keyboard turned away from the medium, made a few sounds; the sitters observed the spontaneous depression of the keys which accompanied the sounds.35Aggazzotti et al. (1907), 377-78.

Imprints on Plaster

Imprints of fingers, hands, fists and faces were obtained in clay and plaster. In one such instance, two blocks of plaster were found to have been impressed with‘a distinct and complete imprint of the plantar surface of a foot’, at a time when the medium’s own hands and feet were verifiably under the control of an investigator.36Bozzano (1903),136; see also Barzini (1907).

Some imprints were quite detailed. Morselli described the photograph of the imprint of a ‘spirit fist’ as showing that it was made

by placing the second phalange of the four fingers and the lower outer edge of the radial or thumb against the impressionable soft substance. That hand is small, and does not have morphological characters that can recognized, also because the pressure shifted somewhat towards the cubital, and the second phalanx of the little finger is seen as split.37Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 394-95.

Materializations

The medium showed many forms of materialization phenomena. One observer wrote of ‘gleams initially very weak, cloudy, like phosphorescent or white, wandering in the cabinet above the body of Eusapia. When they became clearer, they advanced towards the slit of the curtain and appeared to rise vertically, while condensing.’38Courtier (1908), 476.Indeterminate forms and shadows were reported, also animal-like shapes such as a ‘black and opaque shadow having the bizarre form of a large head of a goat, whose elongated nose was going to touch the face of Mr. Schmolz [a sitter] … and gave the impression of a beard.39Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 301.

There were also appearance of body parts. One investigator reported: “I saw a human hand of natural color, and I felt with my hand the fingers and the back of a lukewarm, muscular, rough hand. The hand vanished, and my eyes saw it retreat, describing an arc of a circle, as if entering back into Palladino’s body.40Bottazzi (1909/2011), 165-66, italics in the original.

In the following account an arm was seen while the medium’s hands were visible on the table:

Suddenly the right side of the curtain swelled out and partly covered the fore-arm of the medium … Shortly afterwards my wife, Dr. Venzano and I distinctly saw a hand and an arm covered by a dark sleeve issue from the front and upper part of the right shoulder of the medium. This arm, making its way above the free end of the side of the curtain which was on the table, seized the glass and carried it to Eusapia’s mouth; she leaned back and drank eagerly. After that the arm replaced the glass on the table, and we saw it withdraw rapidly and disappear as if it returned into the shoulder from which we had seen it issue.41Venzano (1907), 100-1.

There were also reports of full-body materializations, as in this example:

We had hardly taken our places again when the curtains opened at some height above the ground, and we saw in a large oval space the figure of a woman holding in her arms a little child, seeming almost as if she were rocking it. This woman, who looked about forty years of age, wore a white cap trimmed with white lace; the cap, whilst hiding the hair, showed the features of a broad face with a high forehead. The remaining part of the body which was not hidden by the curtain was covered with white drapery. As to the child, as far as one could judge from the development of the head and body, it was about three years old. Its little head was uncovered, and had very short hair; it was at a slightly higher level than that of the woman. The body of the child seemed to be enveloped in swaddling clothes, composed also of light and very white material. The woman was looking up affectionately at the child, whose head was slightly bent towards her.The apparition lasted more than a minute. We all stood up and approached it, so that we could perceive the slightest movements. Before the curtain closed again the woman’s head was moved a little forward, whilst the child, bending several times to right and left, repeatedly kissed the face of the woman, so that the sound of the childish kiss reached our ears quite distinctly.42Venzano (1907), 173.

Investigations

While early records are not very detailed, the writings of Damiani43Anon. (1872). and of Chiaia44Chiaia (1890). give us an idea of a few early séances. At Chaia’s urging, the internationally-known criminologist Cesare Lombroso held sittings with Palladino that convinced him of the reality of her phenomena.45Ciolfi (1891). This led to more systematic attempts to evaluate her mediumship, starting in Milan in 1892 with the participation of a number of well-known European scientists and intellectuals, including Charles Richet, a French physiologist, Giovanni Battista Ermacora, an Italian physicist, and Giovanni Schiaparelli, an Italian astronomer. In these sittings Palladino was investigated both in darkness and in good light, and attempts at physical measurement were introduced, using such instruments as a balance and a dynamometer.46Aksakof et al. (1893).

Many more investigations followed.47See Carrington (1909). Two early important ones were held at Île Roubaud in the south of France in 1894, with the participation of Richet, Oliver Lodge, Frederic Myers, and Julian Ochorowicz,48Lodge (1894), 346-57. and in 1895 at Cambridge under the auspices of the Society for Psychical Research, again involving Myers and Lodge, together with their colleagues Henry Sidgwick, Eleanor Sidgwick and Richard Hodgson. Impressive phenomena were reported at Île Roubaud. However, the Cambridge series was a failure: the phenomena were poor and Palladino was repeatedly observed to cheat.

Most later investigations produced positive results.49Carrington (1909). Series of sittings were held at Agnelas in 1895, Genoa in 1901, Paris in 1905-1908, Naples in 1907, Genoa in 1907-1908, and Naples again in 1908. A series of sittings was also given for the benefit of American scientists and intellectuals in New York City between 1909 and 1910.

The Paris series was held at the Institut Générale Psychologique with the participation of Richet, Pierre Curie, Marie Curie, Henri Bergson and others, and the 1917 Naples series, each presents many examples of the use of instruments to provide objective recordings of the occurrences.50Reported by Courtier (1908) and Bottazzi (1909/2011). The variety and interest of the phenomena described in J Courtier’s report of the Paris investigation make it a unique document in the history of psychical research. In addition to biographical details and tests for the occurrence of phenomena, the report describes physical measurements in the area around the medium and studies of her psychology and physiology.

After the failure at Cambridge, the Society for Psychical Research was disinclined to sponsor further research with Palladino. However, the repeated endorsements made by other investigators encouraged the organization eventually to mount a new study of its own, which it held in Naples in 1908 with the participation of Everard Feilding, WW Baggally and Hereward Carrington.51Carrington (1909). This produced one of the strongest reports attesting to the reality of Palladino’s manifestations, considered impressive by virtue of the authors’ extensive previous knowledge of the tricks practised by fake mediums, the stringent controls imposed on the medium, and the clear and detailed chronological account based on stenographic records.

The success of this series encouraged Carrington to arrange a visit by Palladino to America in 1909. Here the participation of sceptics, including Hugo Muensterberg, professor of pyschology at Harvard, Joseph Jastrow, a Polish-born American psycholgist, and Joseph Rinn, a businessman and amateur magician. This resulted in copious negative media publicity, creating the impression that she had been exposed as a cheat.52Alvarado (1993).

Difficulties in Research, Fraud

Palladino allowed investigations of her mediumship and submitted to controls, but could also be difficult to deal with. One researcher wrote:

Eusapia persistently threw obstacles in the way of proper holding of the hands; she only allowed for a part of the time on each occasion the only holding of the feet which we regarded as secure—i.e. the holding by the hands of a person under the table. Moreover, she repeatedly refused any satisfactory test other than holding.53Myers (1895).

The medium could show irritation to the point of unpleasantness, making research difficult. On one occasion when the position of her feet was checked, ‘the medium expostulated for three quarters of an hour, and it was a long time before she again consented to resume and again attempted to go off into the trance state’.54Carrington (1909), 222. Others have noted that Palladino was offended whenever someone showed ‘minimal indecision about the reality of her “phenomena” ’55Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 131. Such doubts could lead her to break off discussions and give vent to ‘the most picturesque and energetic insults of the flowery Napolitan dialect’.56Barzini (1907), 34.

A greater problem for researchers was Palladino’s cheating. At Naples in 1908, there was sufficient light for Carrington to observe the medium twice performing the hand substitution routine, surreptitiously freeing a hand from the control of the investigators.57Feilding et al. (1909), 326. Also observed were her attempts to use a hair to create the appearance of an object moving.58Flammarion (1907), 200-1; Courtier (1908), 521.In one case, an observer watched the medium move her hands towards a balance and saw a ‘luminous ray’ emerge from her fingers. ‘Observing attentively … he realized that the ray was nothing more than a hair reflecting light, and that ultimately the tray of the scale was acted on by the hair stretched between the fingers of the subject’.59Courtier (1908), 521.

More direct observations were made by Gustave Le Bon in 1906:

Thanks to the possibility of producing behind Eusapia an illumination which she did not suspect, we were able to see one of her arms, very skillfully withdrawn from our control, move along horizontally behind the curtain and touch the arm of M. Dastre, and another time give me a slap on the hand.60Flammarion (1907), 104.

Similarly, in Naples she was seen to ‘release the right hand and arm, place it behind her into the cabinet, catch hold of the curtains on that side and throw it out over the table’.61Carrington (1909), 182.

In Paris, on an occasion when an apparatus was being used to produce tracings on a piece of smoked paper, a nail appeared mysteriously on a table, which one participant felt could have come from the medium’s hand. The nail was found to create tracings similar to those which had been observed, and which it had been presumed were produced telekinetically – a circumstance that created suspicion.62Courtier (1908), 523.

In another instance in Paris, Courtier exerted pressure on a levitating table without managing to force it down.He wrote: ‘At this time, the controller of the right side … passed his hand under the table and came across Eusapia’s knee against the rim. He thought she had put her right foot under his left shin, so as to make a fulcrum that allowed her to withstand the pressure exerted by Mr. Courtier on the table top’.63Courtier (1908), 523. On another occasion, a photograph taken without warning when a table was levitating seemed clearly to show that the medium’s hand was raising it.64Courtier (1908), 525-26.

Some observers argued that many of Palladino’s fraudulent acts were an unconscious effect of the trance state, in which she was being induced by other people’s suggestions and expectations to produce phenomena by any means possible.65Ochorowicz (1896).However at least some of her tricks did not seem to have been done unconsciously. Carrington believed Palladino cheated out of ‘love of mischief’.66Carrington (1909), 327.

Psychology, Psychopathology, Medical Aspects

The literature on Palladino includes occasional comments about the medium’s behavior and personality. In Morselli’s view she was not stupid; on the contrary, a shrewd ability to distinguish friends from sceptics enabled her to adapt accordingly.67Morselli (1908),vol. 1, 130.

Another researcher wrote:

She is generally cheerful, sometimes even jovial, but easily prone to outbursts. Her pride is very finicky. She likes to be treated like a great lady. Moreover she is proud of her exceptional faculties and repeats often: ‘There are many doctors and professors, many counts, princes and kings, but in the world there is only one Eusapia!—There is one Eusapia!’68Courtier (1908), 480.

Themedium took offence when she thought she was not being treated properly.69e.g., Lombroso (1907). Barzini described her as ‘choleric and capricious’.70Barzini (1907), 34. Some referred to emotional reactions and to frequent sudden changes of mood.71Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 130-31. At one moment she would be on her knees crying, and then would suddenly start laughing.72Brisson (1898), 2. She could also be violent, prone to ‘fly at her adversaries and beat them’.73Lombroso (1909), 112.

There was also mention of more elevated feelings. According to Courtier she could be charitable. He quoted Richet as saying that, asked what she would like as a present after the completion of an investigation, she requested a hinged prosthesis for a impecunious amputee of her acquaintance in Naples.74Courtier (1908), 480.

Traditionally, Palladino has been described as a ‘hysteric’, a term that was then used differently from today. ‘She passes rapidly from joy to grief, has strange phobias …’75Lombroso (1909), 111-12. Another witness mentioned sighs, yawning and hiccups, and remarked that her face might become ‘demoniacal’.76de Krauz (1894), 172.Morselli said she showed both motor and sensory problems.77Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 126. He also mentioned that Palladino had a history of joint pains and headaches, that she had convulsions that may have been epileptic, and that she was diabetic and suffered from its effects (such as edema of the legs).78Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 126. He further stated that her diabetes was associated with nephritis and that, after not having seen her for five years, the medium looked depleted.79Morselli (1908), vol. 2, 301.

After-effects and Other Physiological Aspects

According to de Rochas, sometimes when the medium wanted to produce phenomena she experienced sensations of ‘numbness and gooseflesh in the fingers’, also sensations ‘in the inferior region of the vertebral column’ like a current continuing to the arm and then to her elbow.80Rochas (1896), 22.After experiencing these sensations, phenomena would sometimes occur.

In common with other physical mediums, Palladino experienced negative after-effects at the end of a séance. She was frequently seen to be exhausted, and even nearly unconscious; in her mid-thirties she once was said to look like ‘an old grandmother’.81de Rochas (1896), 19.Faifofer wrote that he once decided to end a séance early, seeing by her sudden pallor that Palladino was suffering. Shortly afterwards she was overtaken by a vomiting fit.82Faifofer (1903), 577. Lombroso mentioned such symptoms as hallucinations, photophobia and hyperesthesia in the aftermath of a séance.83Lombroso (1909), 115. The medium was said to be ‘very much changed, her eye dull, her face apparently diminished to half its usual size’.84Flammarion (1907), 92.

Palladino also showed sympathetic movements during some of the phenomena, moving her arms or fingers as some effect was taking place at a distance. As explained by Lodge:

Once this was done for my edification with constantly the same object, viz. a bureau in a corner of the room, but with the group of observers and medium (under control as usual of course) first close to it and then gradually further and further away from it, and I was instructed by the agency to observe that the time-interval between the push and the response increased as the distance increased, so that when 6 or 7 feet away the time interval was something like 2 seconds …85Lodge (1894), 333.

A later example was that of a lamp that during a séance repeatedly flashed on and off. This effect, Lombroso wrote, ‘corresponded to a slight movement of the index finger of Eusapia in the hollow of my hand’.86Lombroso (1909), 60.

Several observers commented on Palladino’s tendency towards eroticism during her séances. She exhibited what de Rochas called ‘movements characteristic of erotic ecstasy’87de Rochas (1896), 19. and hysteria of an erotic tendency.88de Krauz (1894), 171. The same writer recorded that Palladino showed an ‘expression of an intense ecstasy, generally of a voluptuous and erotic nature …’, that could be perceived through her shiny eyes, smiles, and movements. In other, more extreme examples of this type of behavior, she threw herself on the arms of surrounding men, embracing them, and showed a ‘desire for caresses …’89de Krauz (1894), 172.

Albert von Schrenck-Notzing noted that while phenomena were occurring the medium showed a great deal of tension, which culminated in attacks of hysterical laughter followed by relaxation. The process seemed painful for Palladino and caused her to whimper like a woman in labour.90Schrenck-Notzing (1920), 67.

Explanations of the Phenomena (Other than Fraud)

A popular early explanation among disbelievers of the reports about Palladino was that sitters and investigators were somehow induced into a hypnotic state, and the ‘phenomena’ they believed they witnessed was in fact hallucinated. This was easily refuted by photographs and recordings of instruments, however.

Many researchers postulated the action of a biophysical force that emanated from the medium’s body, an idea already present in the spiritualist literature of physical mediumship before Palladino came into the scene.91Alvarado (2006). Lodge speculated about ‘vitality at a distance’—the action of a living organism exerted in unusual directions and over a range greater than the ordinary.92Lodge (1894), 334. Others argued that the medium projected her nervous force, combined with that of the sitters, to produce phenomena,93Ochorowicz (1896). and that there was a force that could ‘concentrate itself, materialize, even assume a certain resemblance to a human body, act like our organs, knock violently on a table, touch us’.94Flammarion (1897), 746.

De Rochas hypothesized the existence of a ‘fluidic body’ within the physical body, which in the case of Palladino could condense to produce such physical effects as materializations.Specifically, de Rochas spoke of ‘galvanoplastic transport of the matter of the physical body of the medium, matter that leaves from the physical body to occupy a similar place on the fluidic double’.95De Rochas (1897), 27.

Some assumed that the force was directed by the medium’s mind. Morselli, for instance, thought a ‘bio-psychic ondulatory emanation’ could account for materialization phenomena, which he considered were directed by Palladino’s ‘oniric imagination’, and informed by knowledge that she acquired via telepathy.96Morselli (1908), vol. 1, 449.

Others thought the idea of an emanation of some energy from the medium’s body was insufficient to account for materialization phenomena without also admitting the concept of discarnate agency. This was argued by Bozzano,97Bozzano (1903). Carrington98Carrington (1909). and Venzano.99Venzano (1907).Lombroso initially posited a psychic force that did not involve spirits, but eventually concluded:

Most potent … is the power of the medium in spiritistic matters, so much so that it explains the greater part of the phenomena, but not all; and the complete explanation can be found only by integrating the mediumistic force with another force, which, although it is more fragmentary and transitory, yet acquires, by identifying itself with the medium, a greater potency. And this force … is pointed out to us as found in the residual action of the dead.100Lombroso (1909), 184.

Scepticism and Controversy

Many negative assessments have been made of the claims relating to Palladino, based on her untrustworthy demeanor, the obstacles she raised, her difficult temperament, and her repeated tendency to cheat.101e.g., Kurtz (1985). Two episodes in particular damaged her reputation: the 1895 Cambridge investigation carried out by the Society for Psychical Research and the American sittings in 1910. Palladino is today a key exhibit in the case against mediumship, one that views practitioners as cheats and witnesses of ‘phenomena’ as mistaken or duped.

Many within the research community believed – as many also argue today – that a medium who has once been discovered in fraud is automatically disqualified from serious consideration. This view was strongly promoted by Henry Sidgwick, the founding president of the SPR. Some leaders of the British organization were by-and-large sceptical of this type of physical mediumship, a view reinforced by the findings at Cambridge, and not entirely reversed by the endorsement of the three investigators appointed by the Society in 1908.

The American séance in particular led to damaging media exposure. In the second of two sittings that he attended, the Harvard psychologist Hugo Munsterberg arranged for a colleague to smuggle himself into the room after the séance had begun and observe what was happening under the table. According to a magazine article that Munsterberg later published, the man saw Palladino surreptitiously remove her foot from her shoe – in a way that would not be perceived by the people on each side of her who were supposed to be controlling her feet – and then fish around for the objects behind her, presumably with the aim of making them appear to move.

Employing similar methods, psychologist Joseph Jastrow claimed that Palladino was observed to have succeeded in freeing her feet and hands from the investigators’ control, and to use them to lift the table and cause other effects.102Jastrow (1918), 101-27.When the controls were tightened the effects ceased altogether, he said.

Defenders of Palladino have pointed out that the strategy followed by Richard Hodgson at Cambridge, of effectively allowing the medium to do as she pleased, ensured that cheating would be abundant and made serious observation impossible. This was mitigated by the alternative approach adopted by Carrington, Feilding and Baggally at Naples, which combined a high degree of scrutiny with sufficient control to the point where cheating was prevented – or could be quickly observed – and effects could continue to appear. These investigators also pointed out a clear correlation between lax controls and a lack of interesting effects. By contrast, where the control was good, phenomena seemed abundant.103Inglis (1992).

In 1993 Richard Wiseman, then a lecturer, now professor of psychology at the University of Hertford, argued in the SPR’s journal that despite the precautions described in Naples, the effects seen there could have been performed by a confederate of Palladino – most probably her husband – having gained entrance to the séance room by means of a previously-constructed removable panel in an inside wall in the hotel suite.Critics counter-argued that the presence of a confederate in the circumstances described in the report could not account for all the effects described, and would in any case have quickly been discovered.104e.g., Martínez-Taboas & Francia (1993), Barrington (1992), 324-40.

Defenders of Palladino do not question that she often acted fraudulently, nor that some reports are fail to provide sufficient reassurance about the level of controls in place. But they find some reports indicative that at least some of the phenomena were genuine, arguing for the need to analyze the best evidence rather than focus exclusively on suspicious incidents. For instance Stephen Braude asserts: ‘The crucial issue is not whether there are instances in which the medium cheated, but whether there are instances in which the evidence is strong that no cheating occurred. And in that respect, Eusapia’s case is exceptionally good.’105Braude (2007), 47.

Neverthless, Palladino tends to be absent from present-day discussions of parapsychology, even those that contain sections about early studies of this kind.106e.g., Irwin & Watt (2007).Even many contemporary parapsychologists are unfamiliar with it and averse to considering it, sharing sceptics’ distrust of human testimony and claimed effects of the séance room.

On the other hand, Palladino has received much attention in histories of psi research. Biondi documented her role in the development of mediumship studies in Italy.107Biondi (1988). Her mediumship has also been related to the development of negative views, theoretical and methodological aspects in psychical research,108Alvarado (1993). to practices and attempts to detect deception,109Pettit (2013). and to controversies in American psychology.110Sommer (2013).Palladino continues to be relevant today not just for evidential reasons, but also to help understand the development of mediumship and of psychical research studies.

Carlos S Alvarado (additional material by Robert McLuhan)

Acknowledgement: This article was improved thanks to suggestions received from Dr Massimo Biondi and Dr Nancy L Zingrone.

Literature

Aggazzotti, A., Foà, C., Foà, P., & Herlitzka, A. (1907). The experiments of Prof. P. Foà, of the University of Turin, and three doctors, assistants of Professor Mosso, with Eusapia Paladino. Annals of Psychical Science 5, 361-92.

Aksakof, A., Schiaparelli, G., du Prel, C., Brofferio, A., Gerosa, G., Ermacora, G.B., & Finzi, G. (1893). Rapport de la commission réunie à Milan pour l’étude des phénomènes psychiques [Report of the commission that met at Milan for the study of psychic phenomena]. Annales des Sciences Psychiques 3, 39-64.

Alvarado, C.S. (1982). Note on séances with Eusapia Palladino after 1910. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 51, 308-9.

Alvarado, C.S. (1993). Gifted subjects’ contributions to psychical research: The case of Eusapia Palladino. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 59, 269-92.

Alvarado, C.S. (2006). Human radiations: Concepts of force in mesmerism, spiritualism and psychical research. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 70, 138-62.

Alvarado, C.S. (2011). Eusapia Palladino: An autobiographicalessay. Journal of Scientific Exploration 25, 77-101.

Anon. (1872). Notes and gleanings. Spiritual Magazine 7 (n.s.), 282-87.

Anon. (1918a). Death of Eusapia Palladino. The Times, 18 May, 9.

Anon. (1918b). Nota [Note]. Luce e Ombra 18, 138.

Anon. (1918c). Palladino reported as dead in Rome. The New York Times, May 18, 13.

Arullani, P.F. (1907). Sulla Medianità della Eusapia Paladino [On the mediumship of Eusapia Paladino]. Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier.

Barrington, M.R. (1992).Palladino and the invisible man who never was, Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 58, 324-40.

Barzini, L. (1907). Nel Mondo dei Misteri con Eusapia Paladino [In the world of mysterywith Eusapia Paladino]. Milan: Baldini, Castoldi.

Biondi, M. (1988). Tavoli e Medium: Storia dello spiritismo in Italia [Tables and mediums: History of spiritism in Italy]. Roma: Gremese.

Blondel, C. (2002). Eusapia Palladino: La méthode expérimentale et la “diva des savants” [Eusapia Palladino: The experimental method and the “diva of the savants.”]. In Des savants face à l’occulte 1870–1940, edited by B. Bensaude-Vincent & C. Blondel, 143-71. Paris: La Découverte.

Bottazzi, F. (1909/2011). Mediumistic Phenomena: Observed in a Series of Sessions with Eusapia Palladino. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: ICRL Press.

Bozzano, E. (1903). Ipotesi Spiritica e Teorie Scientifiche [Spiritistic hypotheses and scientific theory]. Genoa, Italy.: A. Donath.

Braude, S.E. (2007). The Gold Leaf Lady and Other Parapsychological Investigations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Brisson, A. (1898). Une soirée avec Eusapia Paladino [An evening with Eusapia Paladino]. Le Temps, December 17, 2-3.

Carrington, H. (1909). Eusapia Palladino and her Phenomena. New York: B. W. Dodge.

Carrington, H. (1954). The American Seances with Eusapia Palladino. New York: Garrett Publications.

Chiaia, E. (1889). Un défi a la science [A challenge to science]. In Congrès International Spirite de Barcelone 1888, 123-27. Paris: Librairie des Sciences Psychologiques.

Chiaia, E. (1890). Expériences médianimiques [Mediumistic experiences]. In Compte Rendu du Congrès Spirite et Spiritualiste International, 326-34. Paris: Librairie Spirite.

Ciolfi, E. (1891). Les expériences de Naples [Tests at Naples]. Annales des Sciences Psychiques 1, 326-32.

Courtier, J. (1908). Rapport sur les séances d’Eusapia Palladino à l’Institut Général Psychologique [Report on the séances with Eusapia Paladino at the Institut Général Psychologique]. Bulletin de l’Institut Général Psychologique 8, 415-546.

de Fontenay, G. (1908). Fraud and the hypothesis of hallucination in the study of the phenomena produced by Eusapia Paladino. Annals of Psychical Science 7, 181-91.

de Krauz, C. (1894). Expériences médianiques de Varsovie (Mediumistic experiences in Warsaw]. Revue de l’Hypnotisme Expérimental et Thérapeutique 9, 1-20, 42-45, 70-79, 106-11, 143-50, 169-79.

de Rochas, A. (1896). L’Extériorisation de la Motricité: Recueil d’expériences et d’observations [The exteriorization of motricity: A compendium of experiences and observations]. Paris: Chamuel.

de Rochas, A. (1897). Les expériences de Choisy-Yvrec (prés Bordeaux) du 2 au 14 octobre 1896 [The experiments of Choisy-Yvrec (near Bordeux) on the 2nd and 11th of October 1896]. Annales des Sciences Psychiques 7, 6-28.

Faifofer, A. (1903). Fenomeni medianici in Eusapia Paladino [Mediumistic phenomena with Eusapia Paladino]. Archivio di Psichiatria, Scienze Penali ed Antropologie Criminale 8 (s. 2), 573-80.

Feilding, E., Baggally, W.W., & Carrington, H. (1909). Report on a series of sittings with Eusapia Palladino. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 23, 309-569.

Flammarion, C. (1897). A séance with Eusapia Paladino: Psychic forces. Arena 18, 730-48.

Flammarion, C. (1907). Mysterious Psychic Forces: An Account of the Author’s Investigations in Psychical Research, Together with Those of other European Savants. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Small, Maynard.

Fontana, D. (1992). The Feilding Report and the determined critic. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 58, 341-50.

Hughes, R. (1908). Seeing things: The most famous of living mediums. Pearson’s Magazine 20, 389-96.

Inglis, B. (1992). Natural and Supernatural: A History of the Paranormal from Earliest Times to 1914 (revised ed.). Dorset: Prism Press.

Irwin, H.J., & Watt, C. (2007). An Introduction to Parapsychology (5th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Jastrow, J. (1918). The Psychology of Conviction. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Kurtz, P. (1985). Spiritualists, mediums and psychics: Some evidence of fraud. In A Skeptic’s Handbook of Parapsychology, ed. by P. Kurtz, 177-223. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Lodge, O.J. (1894). Experience of unusual physical phenomena occurring in the presence of an entranced person (Eusapia Paladino). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 6, 306-36, 346-60.

Lombroso, P. (1907). Eusapia Paladino: Cenni biografici [Eusapia Paladino: Brief biography]. La Lettura 7, 389-94.

Lombroso, C. (1909). After Death—What?: Spiritistic Phenomena and their Interpretation. Boston: Small, Maynard.

Martínez-Taboas, A., & Francia, M. (1993). The Feilding report, Wiseman’s critique and scientific reporting. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 59, 120-29.

Miranda, G. (1918). Eusapia Palladino Intima [Eusapia Palladino an Intimate View]. Luce e Ombra 18, 141-44.

Morselli, E. (1907). Eusapia Paladino and the genuineness of her phenomena. Annals of Psychical Science 5, 319-60, 399-421.

Morselli, E. (1908). Psicologia e “Spiritismo”: Impressioni e note critiche sui fenomeni medianici di Eusapia Paladino [Psychology and “Spiritism”: Impressions and critical notes about the mediumistic phenomena of Eusapia Paladino] (2 vols.). Turin: Fratelli Bocca.

Myers, F.W.H. (1895). Correspondence: Reply to Mr. Page Hopps, concerning Eusapia Paladino. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 7, 164.

Ochorowicz, J. (1896). La question de la fraude dans les expériences avec Eusapia Paladino [The issue of fraud in the tests with Eusapia Paladino]. Annales des Sciences Psychiques 6, 79-123.

Ochorowicz, J. (1913/2018). Zjawiska Medyumiczne [Mediumistic phenomena, part 1] (Translated by Casimir Bernard and Zofia Weaver) part I. Journal of Scientific Exploration 32, 79-154.

Palladino, E. (1910). My own story. Cosmopolitan Magazine 48, 292-300.

Pettit, M. (2013). The Science of Deception: Psychology and Commerce in America. Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Richet, C. (1922). Traité de Métapsychique [Treatise on metapsychics]. Paris: Félix Alcan.

Schrenck-Notzing, A.F. (1920). Physikalische Phaenomene des Mediumismus: Studien zur Erforschung der telekinetischen Vorgänge [The physical phenomena of mediumship: Studies to explore telekinetic operations]. Munich: Ernst Reinhardt.

Sidgwick, H. (1895). Eusapia Paladino. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 7, 148-59.

Sommer, A. (2012). Psychical research and the origins of American psychology: Hugo Münsterberg, William James, and Eusapia Palladino. History of the Human Sciences 25, 2-44.

Venzano, J. (1907). A contribution to the study of materialisations. Annals of Psychical Science 6, 75-119, 157-95.

Wiseman, R. (1992). The Feilding Report: A reconsideration. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 58, 129-52.