Gladys Leonard (1882–1968) was a British trance medium who collaborated extensively with investigators of the Society of Psychical Research in the 1920s and 1930s. Several books and articles discuss aspects of her mediumship, notably ‘proxy’ sittings and the book and newspaper tests, also the processes involved in spirit communication. She was never discovered to be engaging in fraud, nor were substantive accusations of trickery ever made against her.

Contents

Background

Gladys Osborne (her maiden name) was born into a wealthy middle-class family on 28 May 1882 at Lytham, Lancashire. During her childhood, as she later described in her autobiography, she experienced frequent waking visions of beautiful places she named ‘Happy Valleys’, and once saw the ghost of a recently dead neighbour.1Leonard (1931); Ellison (2002), 133-38.Her parents, devout Anglicans, frowned on psychic matters, and she learned to suppress these experiences. In her teens she visited a Spiritualist meeting out of curiosity, to her mother’s disgust.

The family lost its money, obliging Gladys to work at menial jobs while pursuing a career in musical theatre. In 1907, she married the actor Frederick Leonard. In spare moments, together with friends she experimented successfully with table-tipping, and this soon developed into trance mediumship.

Her mediumship gradually matured in the period before World War I, with the support and encouragement of her husband.In 1915, she started sitting with researchers for the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) – first Oliver Lodge, then Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall, a novelist, and Una Troubridge,2Lodge (1918); Radclyffe-Hall & Troubridge (1920). a sculptor and translator – and this provided her with a steady income for the first time. Radclyffe-Hall bought a cottage for her so that she could be conveniently nearby for sittings, and she later acquired a house on the coast at Tankerton, Kent where she lived for much of the rest of her life. She lived quietly, concentrating on her home and garden and devotedly tending her older and more fragile husband until his death. She died in 1968.

Leonard wrote three widely circulated books on her psychic experiences and her reflections on them.3Leonard (1931, 1937, 1942). Her attitude was ethical and professional. She did not read psychical research literature and tried to avoid knowing anything about her sitters.

Although she benefited from a well-off clientele, she also gave sittings to people of limited means. Her connections with the SPR helped ensure that her sitters were for the most part intelligent, serious and committed; many took good records. She was transparently a woman of compassion and integrity: no suggestion of fraud was made by any of those who had many sessions with her and would have been in a position to detect it.

Mediumship

Leonard was a trance medium; that is, she entered a self-induced hypnotic trance at the start of a sitting, and was then taken over by a ‘control’ personality. This personality, named ‘Feda’, identified herself as an Indian ancestor of Leonard’s that died in childbirth around 1800.She spoke with a manner unlike Leonard’s, in a childlike, lisping, high-pitched tone, and usually referred to herself in the third person. It was unclear whether Feda was a genuine discarnate personality, as some researchers believed, or, as others argued, a secondary personality of Leonard’s unconscious mind (see ‘Process’ below).

Leonard’s mediumship is characterized by sittings with a (usually anonymous) sitter, hoping for communication with a lost loved one or acting as a proxy for someone else with the same aim. Her career is also notable for innovative approaches to providing evidence of survival: the newspaper and book tests and proxy sittings (see below).

By agreement with the SPR, between January and April 1918 Leonard gave sittings exclusively to persons whom it sent to her for the purposes of research.4Salter (1950), 25. Seventy-three sittings took place during these months, of which 31 were given to new sitters.The sitters were anonymously introduced and there was a note-taker. Sittings on good days were remarkable for the abundance of precise details connected to a deceased individual. Mostly, the messages were given through Feda, but on occasion individuals spoke through Leonard directly, and in a manner said by sitters to be characteristic of that individual in life.

The early sittings with Oliver Lodge and members of his family were described by him in his book Raymond, Or Life and Death, which was published in 1916 and attracted considerable public notice (see Raymond Lodge). Some of the most substantial and well-recorded sittings were those arranged with Radclyffe-Hall and Troubridge,5Radclyffe-Hall & Troubridge (1920). and with Charles Drayton Thomas, a Methodist minister.6Thomas (1933). Descriptions of these, along with other significant material, are found in the SPR’s Journal and Proceedings and its archive in the Cambridge University library (see full list and summaries below).

As noted above, researchers quickly came to trust Leonard’s integrity, and there was never any suggestion of fraud or suspicious behaviour in relation to her mediumship. At an early stage, Radclyffe-Hall had Leonard’s movements monitored by detectives and made further checks herself, by which she confirmed the medium was not engaging in covert information-gathering activities.7Radclyffe-Hall & Troubridge (1920),343.

A limitation of the research is that Leonard, despite precautions, developed an intensely personal and affectionate relationship with certain people to whom she gave sittings over a long period, which may have affected both the source of the evidence and its objective judgement; this can be seen, for instance, in Ruth Plant’s description of sittings she requested to gain evidence of her brother’s survival after his death in a road accident.8Plant (1972), 149-62. Also, as the war intensified, communications generally appropriate to the deaths of young men were frequently given, and these were often too generic to identify a distinctive individual. (However, some messages and descriptions were highly characteristic of a specific person – see below).9Salter (1950), 25-26.

Sitters

Radclyffe-Hall & Troubridge

Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall obtained a sitting with Leonard in August 1916, hoping to establish communication with her deceased partner Mabel Batten10Radclyffe-Hall & Troubridge (1920). (referred to in the literature as ‘AVB’.)A communicator appeared whose profile closely matched Batten’s, and who, by means of table tilting, gave ‘Watergate Bay’ – the name of the place she and Radclyffe-Hall had last visited together before her death. Encouraged, she and her present partner Una Troubridge embarked on a detailed investigation of Leonard’s mediumship facilitated by Radclyffe-Hall’s considerable income. These were intelligent, cultured individuals who were willing to challenge their personal and subjective responses. Troubridge in particular possessed an excellent memory, a good eye for detail, and knowledge of the literature of dissociation and multiple personality.

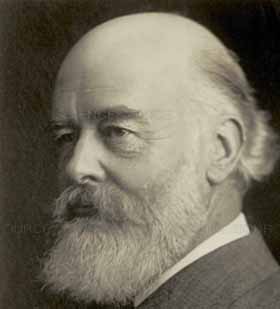

William Brown

William Brown (1929), founder of the first psychology laboratory to be set up at Oxford, devoted a section of his book Science and Personality (1929) to discussing Leonard’s mediumship, following a sitting in which he was given statements from four individuals whom he was able to identify by the details they gave; they were the very ones he had particularly wished to hear from. Brown had observed occasional instances of telepathy and clairvoyance among war veterans suffering shell-shock, but he did not attempt to explain Leonard’s mediumship in terms of pathology.11Brown (1929).

American Visitors

Leonard gave sittings independently to visitors from the United States: Lydia C Allison, John Thomas, and Gertrude Tubby. These were significant for the sitters’ status – well-educated, balanced individuals who had informed themselves of appropriate canons of evidence in psychical research – and also for the geographical distance that would have made it impossible for Leonard to have gained information about their personal circumstances, whether unconsciously or by deception.

Allison’s physician husband died in 1920; he had believed in survival, she did not. She later asked Walter Franklin Prince to evaluate the material, which was somewhat weakened by the fact that she held several sittings over a sustained period, possibly enabling the medium to become familiar with her circumstances. However, Prince pointed out that highly evidential personal details had been given from the start.12Allison (1929), 196-67.

Tubby had worked as secretary for philosopher James Hyslop, a leading member of the American Society for Psychical Research who died in 1920. In a sitting with Leonard she believed she was in communication with the deceased Hyslop.

John Thomas, a senior educational administrator, sought evidence in relation to his wife, who died in July 1926. The success of his early enquiries in the US encouraged him to carry out experiments in England, a study for which he later earned a doctorate. His approach was thorough and meticulous: he often had someone else sit with Leonard as a proxy on his behalf, ensured they were accurately recorded,13Hankey (1963), 102-3. looked for verifiable sources for the medium’s statements among his own records, and discarded unverifiable points, no matter how seemingly persuasive. Of a total of 2,964 specific points that the communicator made, 2,358 were correct, a remarkably high proportion; 196 were incorrect, 231 inconclusive, and 179 unverifiable.14Thomas (1929), 10-11.

Others

Leonard played a significant part in the large-scale investigation that H Dennis Bradley made into the direct voice mediumship of George Valiantine.15Bradley (1926, 1929, 1931). She also participated in a long series of proxy sittings organized by Nea Walker, reported in Walker’s books The Bridge and Through a Stranger’s Hands, which produced evidence tending to support the hypothesis of post-mortem survival.16Walker (1927, 1935).

Proofs of Survival

Evidence of survival in sittings often took the form of descriptions of detailed circumstances known only to the sitter, and in some cases beyond the sitter’s knowledge. As an example of the latter, in a sitting in 1915, statements purporting to originate from the recently deceased soldier son of Oliver Lodge described details of a regimental group photograph whose existence was unknown to them at the time, and which proved to be true. (See Raymond Lodge)

In a sitting in January 1921, Mrs Dawson-Smith heard from a communicator who identified himself as her son. He mentioned an old purse that he said contained a receipt counterfoil. The significance of this became clear when, after the armistice, she received a demand from a Hamburg firm for the payment of a debt incurred by her son in July 1914: she sought out the receipt in the place indicated by the communicator and was able to verify that it had been paid.17Richmond (1938), 78-80.

Lily Talbot

Lily Talbot sat with Leonard in March 1917, giving no name or address, and later sent an account to the SPR (she had not sat with a medium before)18Sidgwick (1921).She first heard descriptions of different people, only some of which were intelligible. Then, she writes,

Feda gave a very correct description of my husband’s personal appearance, and from then on he alone seemed to speak (through her of course) and a most extraordinary conversation followed.Evidently he was trying by every means in his power to prove to me his identity and to show me it really was himself, and as time went on I was forced to believe this was indeed so.

All he said, or rather Feda said for him, was clear and lucid. Incidents of the past, known only to him and to me were spoken of, belongings trivial in themselves but possessing for him a particular personal interest of which I was aware, were minutely and correctly described, and I was asked if I still had them. Also I was asked repeatedly if I still believed it was himself speaking, and assured that death was not really death at all, that life continued not so very unlike this life and that he did not feel changed at all.19Sidgwick (1921), 254.

Then came a description of an old leather notebook of his, which Feda was insistent she should find and then look for something important on page 12 or 13. This talk did not much interest her; she thought she had thrown the notebook away.But to her annoyance, Feda persisted for some time, offering suggestions as to how she might identify the notebook and the extract, and referring to ‘Indo-European, Aryan, Semitic languages’, ‘A table of Arabian languages, Semitic languages’, ‘table’, ‘diagram’ and ‘drawing’. Talbot was not inclined to comply, but mentioning it to her niece that evening was urged by her to seek it out. In the end, she writes,

I went to the book shelf, and after some time, right at the back of the top shelf I found one or two old notebooks belonging to my husband, which I had never felt I cared to open. One a shabby black leather, corresponded in size to the description given, and I absent-mindedly opened it, wondering in my mind whether the one I was looking for had been destroyed or only sent away. To my utter astonishment, my eyes fell on the words, “Table of Semitic or Syro-Arabian Languages,” and pulling out the leaf, which was a long folded piece of paper pasted in, I saw on the other side “General table of the Aryan and Indo-European languages.” It was the diagram of which Feda had spoken. I was so taken aback I forgot for some minutes to look for the extract.20Sidgwick (1921), 256.

When she did so she found on page 13 a passage copied from a book describing purported conditions of post mortem survival:

I discovered by certain whispers which it was supposed I was unable to hear and from glances of curiosity or commiseration which it was supposed I was unable to see, that I was near death …

Presently my mind began to dwell not only on happiness which was to come, but upon happiness that I was actually enjoying. I saw long forgotten forms, playmates, school-fellows, companions of my youth and of my old age, who one and all, smiled upon me. They did not smile with any compassion, that I no longer felt that I needed, but with that sort of kindness which is exchanged by people who are equally happy. I saw my mother, father, and sisters, all of whom had survived. They did not speak, yet they communicated to me their unaltered and unalterable affection. At about the time when they appeared, I made an effort to realise my bodily situation … that is, I endeavoured to connect my soul with the body which lay on the bed in my house … the endeavour failed. I was dead …” Extract from Post Mortem. Author anon. (Blackwood & Sons, 1881).21Sidgwick (1921), 257.

Proxy Sittings

Notably successful proxy sittings are described by Drayton Thomas in the SPR Proceedings.22Thomas (1939). Here, no one was present who knew the deceased person or who knew anything about the circumstances of their life and death, excluding any possibility that medium picked up information from a sitter by telepathy or visual clues.

Bobbie Newlove

Bobby Newlove died in 1932, aged ten, having contracted diphtheria. He was the son of the stepdaughter of a Mr Hatch; the family lived in the Lancashire town of Nelson. Some weeks after the boy’s death, Hatch contacted Charles Drayton Thomas who was having sittings with Leonard for research purposes; the family had read his book Life Beyond Death and asked if, in his work with Leonard, he might produce evidence of Bobby having survived death.

In eleven sittings, a large number of statements were made about Bobby and the manner of his death. Of these, 100 were specific and correct with regard to the actual circumstances:for example, the Jack of Hearts fancy dress costume he had once worn, gymnastic exercises he practised and the equipment he used. Thirty eight more general statements were vaguely relevant, and 26 were poor. Only seven were actually wrong.23Thomas (1935).

Of particular interest in this case were repeated statement that Bobby had picked up the infection from playing near pipes that produced contaminated water, in a location he did not normally frequent. This circumstance was hitherto unknown. Thomas and the family were able to discover a spot that closely corresponded to the descriptions: a local person confirmed that Bobby and other children came to play there and had broken the pipe that carried spring water from the hills, causing water to accumulate in pools. The water was found to be contaminated and a risk to health.

Frederick William Macaulay

A similarly productive series of the proxy type was initiated in 1936 by Thomas at the suggestion of ER Dodds, an Oxford classics professor and sceptic of survival. The sittings were held on behalf of a Mrs Stanley Lewis who wished to try to contact her father Frederick William Macaulay, who had died three years earlier. Feda made a number of statements that closely corresponded to the dead man’s interests and life circumstances, in particular certain family jokes. In one instance, she mentioned various names of people that had been connected with the Macaulay household, including ‘Race … Rice … Riss … it might be Reece but sounds like Riss’. Macaulay’s daughter found this especially significant, as her elder brother had had a school friend named Rees, and was insistent that it should be pronounced correctly.

In another instance, Feda repeated the word ‘baths’, which she understood would have special significance to the family: ‘His daughter will understand, he says. It is not something quite ordinary, but feel something special.’ Mrs Lewis wrote:

This is, to me, the most interesting thing that has yet emerged. Baths were always a matter of a joke in our family – my father being very emphatic that water must not be wasted by our having too big baths or by leaving the taps dripping. It is difficult to explain how intimate a detail this seems. A year or two before his death my father broadcast in the Midland Children’s Hour on “Water Supply” and his five children were delighted to hear on the air the familiar admonitions about big, wasteful baths and dripping taps. The mention of baths here also seems to me an indication of my father’s quaint humour, a characteristic which has hitherto been missing.24Thomas (1939), 266.

Cross-Correspondences

A Leonard sitting might contain a striking cross-reference or ‘cross-correspondence’. Florence Barrett sat with Leonard following the death in 1925 of her husband William F. Barrett, the physicist and co-founder of the Society for Psychical Research. She had not planned to do so, but was intrigued by the experience of another Leonard sitter, who reported having had the ‘vivid impression’ of Barrett communicating.25Barrett (1937), xl-xlvi.At the sitting, ‘Barrett’ stated that he had sent her a message from a place a very long way off. A friend named Mrs Jervis, who had been unable to keep an appointment for afternoon tea with Barrett because of his death, later told her that she had received a letter from Leonora Piper, a medium in America with whom she was acquainted, saying a communicator had stated, ‘Tell Mrs. Jervis I am sorry I could not keep the appointment.’

Book Tests

Tests involving books were carried out in an attempt to rule out the possibility that the information given to a sitter with Leonard was coming, not from a deceased individual, but from the sitter herself by means of unconscious telepathy with the medium. Typically, a communicator described the appearance and location of a book in the sitter’s home (which would have been unknown to Leonard), indicating first its position in the bookshelves, then a particular word or passage in that book by page number and position on that page. The communicator might then indicate what word or idea would be found there. (An example is the Talbot case described above.)

In one successful, comparatively straightforward example, a book was indicated in shelves in the sitter’s home as the second from the left, with a light blue cover, on a shelf that contained books with notably contrasting colours.The text selected was on page fifteen, about a quarter of an inch above the middle of the page. The communicator had some difficulty describing the idea associated with this text, but eventually gave the image of someone ‘grasping a long upright pole or stick’. The directions led to a copy of Henry James’s Daisy Miller and on page fifteen, starting a quarter of an inch above the middle of the page, was found the following:

“I should like to know where you got that pole,” she said.

“I bought it!” responded Randolph.26Sidgwick (1921), 286-89.

The pole is described on page 14 as an alpenstock, and on page 12 as a long alpenstock, a staff used by Swiss shepherds.

In many cases, the relevance of the text would be immediately apparent to the sitter. Pamela Glenconner reported an incident that occurred during a December 1917 séance with Leonard, in which her son Bim, recently killed in the war, appeared to communicate.Bim’s father, Lord Glenconner, was keenly interested in forestry and obsessively concerned about the damage that beetles might do to trees in his estate. This became a family joke: whenever his father was in a particularly gloomy mood, Bim would say, ‘All the woods have got the beetle.’ In a sitting held in December 1917, Feda stated that Bim was sending a message intended for his father, that would be found in a book in the family home, as follows: ‘It is the ninth book on the third shelf counting from left to right in the bookcase on the right of the door in the drawing-room, as you enter; take the title, and look at page 37.’ The book indicated was found to be titled Trees, and at the top of page 37 was found the phrase ‘… a tunnelling beetle, very injurious to the trees …’.27Glenconner (1921), 58-61.

Eleanor Sidgwick analysed 532 Leonard book tests, finding that complete successes accounted for 17 percent and partial successes 36 percent.28Sidgwick (1921). A control experiment with fabricated book tests produced 1.9 percent complete success and 4.7 percent partial success.29Anon. (1923). Other control experiments that used different approaches yielded similar results.30Besterman (1931).

Despite their ingenuity, the evidence from book tests does not completely circumvent the possibility that it originated from living minds by means of telepathy or clairvoyance. Several are highly literary, and correspondingly obscure, and the possibility remains that the appearance of a connection was generated by chance or wishful thinking. Parapsychologists today would prefer judgement to be provided collectively by a panel rather than a single assessor, no matter how competent, and that control passages be included besides the target.31Beloff (1993), 122-23. They would also insist on more rigorous precautions against sensory leakage, treating with caution reports of sittings given when Leonard was lodging with a person intimately known to the sitter’s family.32Lodge, in Glenconner (1921).

It should also be noted that several tests referred to the deaths of young people, a preoccupation during and after World War I, and also a frequent theme in literature, raising the possibility of spurious, chance matches. For example, the phrase ‘Here scattered death; yet seek the spot, No trace thine eye can see …’ was indicated in a sitting in relation to the obliterated grave of a soldier killed in the Middle East.33Smith (1964), 149.

Nevertheless, it remains true that strikingly meaningful matches were found well above the rate that would be expected to occur by chance in books situated in bookcases and in rooms to which the medium in the great majority of case had no possibility of prior access.

Newspaper Tests

Similar tests with newspapers involved a precognitive element, the communicator forecasting a word or idea associated with statements to be found on a certain page in tomorrow’s issue of a daily publication. Some statements that were later verified were made even before the print type was set up. This innovation originated in 1919 in sittings organized by Charles Drayton Thomas.34Thomas (1948), 105-9.

In one case, Thomas was directed to look at a particular page in a newspaper, where, a quarter of the way down column two, he would find his father’s name, his own, his mother’s and that of an aunt, all within two inches of text. Thomas did so, and found within the indicated text his father’s first name ‘John’, followed by his own, ‘Charles’, and then the name ‘Emile Sauret’, which he realized closely approximated to his mother’s name ‘Sarah’, and that of his aunt Emily.

Thomas calculated that 73 out of 104 of these early results could be classed as successes. When he looked to see whether similar matches might be found in the indicated location in issues of different dates, he found only 18.

Thomas also recorded accurate predictions of future events made in Leonard sittings, some apparently originating from an old friend, a former MP, and others from his own father.35Thomas (n.d.), 13. Thomas viewed this not as an exercise in fortune telling, but as an important element in the increasing evidence for survival, demonstrating that the deceased remained close to loved ones still incarnate. (Here too, the possibility of Leonard obtaining information from sources such as the newspaper typesetter by wide-ranging unconscious clairvoyance cannot be ruled out.)

Process

There was much comment and speculation among researchers regarding the processes involved in Leonard’s mediumship.

For the most part, communications purporting to come from discarnates were made indirectly, with Feda acting as go-between.36Salter (1950), 35-40. More rarely, the personalities ‘controlled’ Leonard directly; that is, they spoke using her vocal organs, although apparently with much difficulty (see below).

One area of uncertainty was whether Feda herself should be regarded as a discarnate – as those for whom she relayed messages appeared to be – or rather as a ‘secondary personality’, a creation of the medium’s unconscious mind.Feda represented herself as the teenage Indian bride of William Hamilton, Leonard’s great-great-grandfather. No such person has been traced – at the turn of the nineteenth century there was much inter-marriage between employees of the East India Company and the indigenous population, and the records contain the names of several William Hamiltons37For example, a William Hamilton appears in the East India Company Pensions List in 1818. See www.findmypast.co.uk – although this alone does not exclude the possibility that she existed.

Una Troubridge drew attention to the similarity of the Feda personality to certain well-documented cases of multiple personality, also to the controls of other mediums, in particular with regard to her childish and capricious characteristics.Examples are ‘Margaret’ and ‘Sally’ in the Doris Fischer and Beauchamp cases (both of multiple personality) and ‘Nellie’, ‘Minnehaha’ and ‘Moyenne’ in the mediumship of Rosalie Thompson, Minnie Soule (‘Mrs Chenoweth’) and Stanislawa Tomczyk respectively.

Doris Fischer’s dominant alter ‘Margaret’ appeared to dislike Doris, and subjected her to various torments. Likewise, Feda appeared to have a low opinion of Leonard, expressing scorn of her opinions, likes and dislikes. She was also cavalier with regard to Leonard’s personal property. Troubridge writes: ‘Feda, according to Mrs. Leonard, has twice presented to casual sitters Mrs. Leonard’s wedding ring, has once thrown it in the fire, from which a distressed sitter rescued it, and once ordered another sitter to bestow it upon an itinerant organ grinder.’38Troubridge (1922), 353-54. When Leonard placed a fur coat over her knees at the start of a sitting, instead of the blanket she habitually used, Feda ripped it up, objecting to the presence of ‘dead animals’. On another occasion, she insisted that Leonard give her costly ruby ring to a domestic servant.39Troubridge (1922), 354-55. According to Troubridge, Leonard tended to comply with Feda’s whims, as otherwise Feda would punish her by not appearing at sessions, effectively threatening her livelihood.

Both ‘Margaret’ and ‘Feda’ claimed to have co-consciousness of their hosts’ thoughts and activities in the periods when they were inactive, while both Fischer and Leonard had no memory of anything that occurred while these personalities were dominant.40Troubridge (1922), 356-57.

Like some other child controls, Feda’s pronunciation was childlike – she habitually substituted an L for an R – and she did not respond to attempts to correct it. She habitually referred to herself in the third person and called regular sitters by childish nicknames such as ‘Twonnie’ and ‘Raddy’. (A recording of Leonard speaking in trance as ‘Feda’ can be heard here.)41Recordings of Unseen Intelligences 1905-2007. Berlin: Supposé.

On the other hand, despite the production of much inaccurate and unverifiable material, Troubridge considered that Feda had a deep respect for the truth.42Troubridge (1922), 356.

[S]he very often appears scrupulously anxious to convey only what is strictly accurate, and we may perhaps seek the reason for this in one of her own utterances, when enlarging upon her duties as an honest and conscientious control. “This work is Feda’s ploglession, if Feda told lies, Feda wouldn’t plogless.” In any case her tender conscience is recognisably akin to that which led Margaret to tell Dr. Prince: “Papo, I think I thunk a lie.”

In the 1930s, Whately Carington reported in several papers on his attempts, using Carl Jung’s word association method, to determine whether or not trance personalities such as Feda could be decisively identified as aspects of the mediums’ consciousness rather than spirits of deceased individuals.He statistically analysed their responses from trance personalities for reaction times and physiological reflexes and compared them to those for the medium during a normal state. He concluded that Feda was likely to be a secondary personality.43Carington (1935). However, methodological flaws were later identified that make this conclusion uncertain.44See also Richmond (1936); Tyrrell (1961), 206-20.

The complex relationship between mediumship and dissociation has been perceptively explored by philosopher Stephen Braude. It remains the case that, even if Feda was a substantial and sustained fragment of Leonard’s subconscious mentation (the dissociation hypothesis), much of her material appeared to provide evidence for survival (the survival hypothesis). In fact, the confusion caused by these dissociated fragments, and the conflict between them, may have allowed the intrusion or insertion of genuine discarnate communication (the intrusion hypothesis). Braude reaches no firm conclusion, but his study clarifies the issues and underlines the amount of empirical and philosophical work required to make an informed judgement.

See also a detailed discussion by British psychologist and parapsychologist Alan Gauld of the processes involved in mental mediumship, which includes consideration of Leonard and ‘Feda’. Gauld draws attention to Eleanor Sidgwick’s voluminous study of the controls of Leonora Piper45Sidgwick (1915). and her conclusion that these are almost certainly constructs of Piper’s unconscious, inferring that this also applies to Leonard. However, Sidgwick came also to believe that genuine spirit communication was involved, in a process that Gauld names ‘overshadowing’.46Gauld (1982), 109-29.

Direct Voice

Charles Drayton Thomas drew attention to a less well-remarked aspect of Leonard’s mediumship, the phenomenon of ‘direct voice’.47Thomas (1946); Gaunt (2016), 51-55.This was a major characteristic of certain mediums, notably Leslie Flint and Etta Wriedt, where voices off different timbres and characteristics were heard that appeared to be independent of them. In Leonard’s case, the voices were heard only occasionally and were barely audible, apparently those of discarnates giving messages for Feda to relay to sitters. Typically, they were heard correcting Feda on some point, for instance:

Feda: A man once said Feda was a spectrum

Direct voice: Spectre, not spectrum!48Smith (1964), 233.

and

Feda: Tell her that he is happy, that he can see nothing in this life that he would wish to see altered.

Direct voice: New life.

Feda: In the new life that he would wish altered.

Thomas held that this encourages a literal view of the communicators being present in a quasi-physical sense, possessing ‘bodies’ visible to Feda and occupying definite places in the séance room.

In his work with Leonard, Thomas was in regular contact with personalities he believed to be his deceased father and sister, who described to him the process of communication and the difficulties involved. A circle of power/light was said to emanate from the medium – and to some extent from others present at the sitting – into which discarnates might enter.49Smith (1964), 207-24. By this means they established contact with Feda, with whom they could then converse, directly or telepathically through images, symbols and impressions. However, entering the circle caused the discarnates to become dazed, compromising their ability to recall certain details from their memory. This is why Feda often appears to be gradually feeling her way to a conclusion, a circumstance that sceptical commentators might prefer to see as evidence of cold reading.

Occasionally, Feda is persuaded to step aside and allow the communicators to take control of the medium directly. However, they state that their control is imperfect, and that Leonard’s vocabulary and memory may cause what they intend to say being misinterpreted.

Afterlife

Leonard’s sittings, notably those with Drayton Thomas, offered details about the postmortem state: the transition to the afterlife, the afterlife itself, and the nature of the spiritual body. There is a consistent emphasis on the afterlife as a substantial, tangible place, in which individuals, having shed the physical body, take the form of an etherial/spiritual body that retains many of the qualities of the physical body but in a finer, more enhanced form.50Plant (1972), 31. It is difficult to assess the origin of this: whether from Leonard’s early involvement in the Spiritualist movement, some involvement with Theosophy, or from the influence of Oliver Lodge,51Asprem (2014), 218-20. a leading SPR researcher, whose sittings with Leonard produced similar material with regard to his son Raymond, a casualty of World War I.

Some of these descriptions are found in her autobiography. They were also widely publicized in Claude’s Book and Claude’s Second Book, based on sittings that began in March 1916 in which an airman killed the previous November appeared to communicate with his mother Mrs Kelway-Bamber, answering questions about the next world. The books entered the Spiritualist canon; although they provided comfort to the bereaved, they have little evidential value.

Criticism

Sceptics of mediumship have disputed the claims relating to Gladys Leonard on a number of grounds. They correctly point out that Leonard had long and regular contact with certain sitters who became personal friends, raising the possibility that evidence might become contaminated. It is also conceivable that the trance did not preclude the overhearing of casual asides or whispered comments by the sitters that might have provided information, although this has not been established.

Critics also highlight questions about her control personality Feda, citing researchers such as Whately Carington, who concluded that she was a secondary personality originating in Leonard’s unconscious mind, not a discarnate individual.

Certain authors have portrayed Leonard as a cheat,52Souhami (1998), 88-93, 101-3. claiming that she gained information about sitters by cold reading or intelligence gathering, and that sitters’ validation of the material, being subjective, is unreliable. With regard to details given to Oliver Lodge about a regimental group photograph in which his deceased son Raymond was pictured – which Lodge at that time had not seen, and was certain that Leonard had never seen – it has been claimed that she contrived to gain sight of it during the short interval between copies being printed and a copy reaching the Lodge family.53Lodge (1916); Mann (1919), 187-88. Lodge’s competence as a researcher is also questioned.54Brandon (1983), 213-19.

Some of these concerns – for instance about the effect of prolonged contact with regular sitters and the status of Feda – originated in debates among the researchers themselves, some of whom disputed survival but who almost all agreed about a paranormal process at work in Leonard’s mediumship. For instance the Oxford classicist ER Dodds analyzed key Leonard material in depth, concluding that she had high gifts of telepathy and clairvoyance, but that individual survival was not proved.55See Thomas (1939), 257-306; Dodds (1934), 147-72.

In other cases, the critics’ grasp of the issues is in question, for instance when one author finds the 36% accuracy level found in the book tests to be unconvincing,56Douglas (1982), 155. when their complexity means that very few could occur by chance, as was confirmed by a control study that resulted in a 7% success rate (see above).

Some critics show no awareness of the conditions under which Leonard sat, confusing them with séances held in complete darkness by physical mediums, about which charges of fraud can more legitimately be made. Claims that Leonard employed fishing and cold reading take no account of the fact that she was in a trance, as was reliably verified, and had no memory of what she said in that state.57McLuhan (2010), 132-35. When sceptics criticize Lodge’s willingness to accept evidence of his son Raymond’s survival as credulous, they disregard his description of the gradual effect on his mind of hearing abundant details of intimate family life given by ‘Raymond’, some of which was unknown to him at the time.58Johnson (2015), 78.

Accusations about Leonard’s integrity are hard to sustain, in view of the almost complete lack of supporting evidence for fraud of any kind. There are counter-indications that the charge is baseless. As stated above, Radclyffe-Hall hired detectives to check whether Leonard was seeking out information she might later present in sittings, but no suspicious activity was observed.59Radclyffe-Hall & Troubridge (1920), 343. Muriel Hankey, the stenographer who was present at sittings over many years and would have had ample opportunity to observe any wrongdoing on Leonard’s part, stated: ‘She was one of the most honourable people, a very charming Christian woman.’60Rauscher (2005), 109-13.

Trevor Hamilton

Literature

Allison, L. (1929). Leonard and Soule Experiments in Psychical Research. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Boston Society for Psychic Research.

Anon. (1923). On the element of chance in book-tests. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 33, 606-20.

Asprem, E. (2014). The Problem of Disenchantment: Scientific Naturalism and Esoteric Discourse. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill.

Barrett, F. (1937). Personality Survives Death: Messages from Sir William Barrett Edited by His Wife. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

Beloff, J. (1993). Parapsychology: A Concise History. London: The Athlone Press.

Besterman, T. (1931). Further inquiries into the element of chance in book-tests. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 40, 59-98.

Blatchford, R. (1925). More Things in Heaven and Earth: Adventures in Quest of a Soul. London: Methuen.

Brandon, R. (1983). The Spiritualists: The Passion for the Occult in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Bradley, H. (1926). Towards The Stars. London: T. Werner Laurie.

Bradley, H. (1929). The Wisdom of the Gods. London: T. Werner Laurie.

Bradley, H. (1931). …And After. London: T. Werner Laurie.

Braude, S.E. (2003). Immortal Remains: The Evidence for Life after Death. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Braude, S.E. (2013). The possibility of mediumship: Philosophical considerations. In The Survival Hypothesis: Essays on Mediumship, ed. by A.J. Rock, 21-39. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Broad, C.D. (1962). Lectures on Psychical Research. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Brown, W. (1929). Science and Personality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Byrne, G. (2012). Leonard, Gladys Isabel Osborne (1882–1968), Spiritualist and trance medium. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Carington, W. (1935). The quantitative study of trance personalities II. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 43, 319-61.

Dellamora, R. (2011). Radclffye Hall:A Life in the Writing. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Dodds, E. (1934). Why I do not believe in survival. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 42, 147-72.

Douglas, A. (1982). Extra-Sensory Powers: A Century of Psychical Research. Overlook Press.

Doyle, A.C. (2002). The History of Spiritualism, Vol. 2. Surrey, UK: Spiritual Truth Press.

Ellison, A. (2002). Foreword to Science and the Paranormal: Altered States of Reality, by D.Fontana. Edinburgh, UK: Floris.

Fontana, D. (2005). Is There an Afterlife? A Comprehensive Overview of the Evidence. Hampshire, UK: O Books.

Gauld, A. (1982). Mediumship and Survival: A Century of Investigations. London: Heinemann.

Gaunt, P. (ed.) (2016). Independent voice development with Mrs. Osborne Leonard – Light. Psypioneer Journal12/2, 51-55.

Glenconner, P. (1921). Preface to The Earthen Vessel: A Volume Dealing with Spirit-Communication Received in the Form of Book-Tests, by O. Lodge. New York: John Lane.

Hankey, M. ( 1963). James Hewat McKenzie, Pioneer of Psychical Research. London: Aquarian Press.

Hansel, C. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-Evaluation. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus.

Heywood, R. (1959). The Sixth Sense:An Enquiry into Extra-Sensory Perception. London: Chatto & Windus.

Heywood, R. (1969). Mrs Gladys Osborne Leonard: A biographical tribute. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 45, 95-115.

Johnson, G. (2015). Mourning and Mysticism in First World War Literature and Beyond: Grappling with Ghosts. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Keen, M. (2002). The case of Edgar Vandy: Defending the evidence. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 66, 247-59.

Kelway-Bamber (ed.) (1919). Claude’s Book. New York: Henry Holt.

Kelway-Bamber (ed.) (1920). Claude’s Second Book. New York: Henry Holt.

Kollar, R. (2000). Searching for Raymond: Anglicanism, Spiritualism, and Bereavement between the Two World Wars. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Leonard, G. (1931). My Life in Two Worlds. London: Cassell.

Leonard, G. (1937). The Last Crossing. London: Cassell.

Leonard, G. (1942). Brief Darkness. London: Cassell.

Lodge, O. (1918). Recent evidence about prevision and survival. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 29, 111-69.

Mann, W. (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. London: Watts & Co.

McLuhan, R., & Weaver, Z. (eds.) (2003). SPR Abstracts Catalogue. Gladys Osborne Leonard. [Web page]

McLuhan, R. (2010). Randi’s Prize: What Sceptics Say about the Paranormal, Why They are Wrong, and Why it Matters. Leicester: Matador.

Murphy, G., with Dale, L. (1970). Challenge of Psychical Research. A Primer of Parapsychology. New York: Harper.

Nickelson, D. (2010). Mrs Osborne Leonard: Her life and mediumship. Light, 1965. Psypioneer Journal 6/5, 118-124.

Nickelson, D. (2010). The mediumship of Mrs Osborne Leonard – Later years: New facts and factors. Psypioneer Journal 6/5,125-29.

Ormrod, R. (1984). Una Troubridge, the Friend of Radclyffe-Hall. London: Jonathan Cape.

Plant, R. (1972). Journey into Light: An Account of Forty Years’ Communication with a Brother in the After Life. London: Cassell.

Radclyffe-Hall, M., & Troubridge, U. (1920). On a series of sittings with Mrs Osborne Leonard. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 30, 339-554.

Rauscher, W. (2005). Thoughts of Muriel Hankey. Psypioneer Journal 1/11, 109-13.

Richmond, K. (1936). Preliminary studies of the recorded Leonard material. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 44, 17-52.

Richmond, K. (1939). Evidence of Identity. London: Bell & Sons.

Richmond, Z. (1938). Evidence of Purpose. London: Bell & Sons.

Salter, H. (1922). A further report on sittings with Mrs Leonard. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 32, 1-143.

Salter, W. (1950). Trance Mediumship: An Introductory Study of Mrs Piper and Mrs Leonard. Glasgow, UK: Society for Psychical Research.

Sidgwick, E. (1915). A contribution to the study of the psychology of Mrs Piper’s trance phenomena, Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 28, 1-652.

Smith, S. (1964). The Mediumship of Mrs. Leonard. New York: University Books.

Sidgwick, E. (1921). An examination of book-tests obtained in sittings with Mrs Leonard. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 31, 241-416.

Souhami, D. (1998). The Trials of Radclyffe-Hall. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Sudduth, M. (2016). A Philosophical Critique of Empirical Arguments for Postmortem Survival. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thalbourne, M. (1998). The evidence for survival from Sir Oliver Lodge’s Raymond. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 63, 34-39.

Thomas, C.D. (1935). A proxy case extending over eleven sittings with Mrs Osborne Leonard [‘Bobbie Newlove’]. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, 43, 439-519.

Thomas, C.D. (1939). A proxy experiment of significant success. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 45, 257-306.

Thomas, C.D. (1946). A new hypothesis concerningtrance-communications. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 48, 121-63.

Thomas C.D. (1947). Life Beyond Death With Evidence (2 vols). London: Psychic Book Club.

Thomas, C.D. (1948). Some New Evidence For Human Survival. London: Spiritualist Press.

Thomas, C.D. (n.d.). Precognition And Human Survival. A New Type of Evidence. London: Psychic Press.

Thomas, J. (1937). Beyond Normal Cognition: An Evaluative and Methodological Study of the Mental Content of Certain Trance Phenomena. Boston, Massachussetts, USA: Boston Society for Psychic Research.

Troubridge, U. (1922). The ‘modus operandi’ in so-called mediumistic trance. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 32, 344-78.

Tubby, G. (1929). James H. Hyslop-X, His Book: A Cross Reference Record. York, Pennsylvania, USA: The York Printing Company.

Tyrrell, G. (1961). Science and Psychical Phenomena and Apparitions. New York: University Books.

Walker, N. (1927). Prologue/Epilogue by Oliver Lodge. In The Bridge. A Case for Survival. London: Cassell.

Walker, N. (1935). Through a Stranger’s Hands. New Evidence for Survival. London: Hutchinson.

West, D. (2000). The AVB communications via Mrs Leonard: Looking back at a historic case record. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 64, 233-41.