Carl Edon (1972–1995) was an Englishman who as a child expressed detailed memories of having been a German pilot shot down during World War II. This claim appeared to be supported by certain behaviours and physical features. His parents and others believed that the past life pilot’s identity has been established, but this is disputed by experienced researchers.

Contents

Memories

Carl Edon was born in Middlesborough, UK, on 29 December 1972 to James and Valerie Edon.1Stevenson (2003), 68. All information in this article is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted. Able to speak coherently from age two, young Carl began almost immediately to repeat the phrase ‘I crashed a plane through a window,’ gradually adding more details about an apparent past life. He had been shot down while on a bombing mission over England, he said, later adding that the plane was a Messerschmitt 101 or 104 and that his right leg had been severed in the crash. He gave his name as Robert, and those of his father and brother as Fritz and Peter. He described his mother as dark, bespectacled and bossy. He had been 23 years old at death, he said, leaving a fiancée of nineteen who was blonde and slender.

Carl said that he had joined the German air force at age nineteen. He described the huts in which he had lived while training, and other details, such as the men stamping while saluting a portrait of Hitler and treating each other’s injuries. His parents were able to verify his description of his training uniform and other details as accurate.

With regard to his early past life, Carl remembered a childhood spent in a small village amidst lushly-wooded hills, and his father instructing him about trees and flowers during country walks. He also remembered smells, such as those of the firewood he had to gather and chop as part of his household chores, and the thick dark red soup his mother made.2Harrison & Harrison (2013), 32-33.

Investigators Peter and Mary Harrison paraphrased his memories of the fatal crash as follows:

He was flying low over some buildings and he must have lost consciousness for a few moments: as he described things, ‘It went all black for a moment.’ When he came round in the cockpit of his plane he was aware of a building rushing towards him at great speed. He desperately wrenched at the controls in a frantic effort to avert the collision, but he was too late. The plane bulldozed its way right through the large glass windows of the building. Carl remembers the horrendous sensation which swept over him as he realized that he had lost his right leg. The shock of the crash, and the loss of his limb, combined with his other injuries, affected him so severely that he died very shortly after the crash … He remembered his thoughts just before he died and how he felt great compassion for his young fiancée, knowing that she would ultimately be given the shattering news of his death. In Carl’s typical understatement, ‘I felt so sorry for her.’3Harrison & Harrison (2013), 32.

Matching Behaviours

Carl displayed behavioural signs of having been the person he described. As early as age two, he began drawing aeroplanes, badges and other insignia including swastikas and the German-style eagle; his parents were struck by their precision and neatness.4Harrison & Harrison (2013), 30. At the age of six he drew the control panel of an aeroplane and described the function of each gauge and control, including the red pedal used to release the bombs. Whenever family friends asked him to tell them what he wore, or requested a sketch of an object from his previous life, he would oblige. Unfortunately, none of the sketches have been preserved.

Carl also showed a fascination with Germany, saying he wanted to live there. Watching TV programs about wartime Germany, he commented on errors, such as a uniformed actor having a badge in the wrong place. He spontaneously demonstrated the straight-armed Nazi salute and the ‘goose-stepping’ Nazi style of marching. When a school play included a German character, Carl insisted on playing him. His preferences with regard to food and drink resembled those of German people: unlike other family members he liked thick soups and sausages, and preferred coffee to tea.

Matching Physical Features

Carl also had some indicative physical signs, including anomalous pigmentation: in contrast to other family members,his hair, eyebrows and eyelashes were all light blond and his eyes were blue. His parents speculated that a large raised birthmark on the right side of his groin might be related to his previous incarnation’s injury; by adulthood it had become so prominent that he had it surgically removed

Investigations

The Harrisons interviewed the family in 1982 when Carl was nine and included the case in their book The Children That Time Forgot.5Harrison & Harrison (2013), 30-34. Ian Stevenson learned about it from an article published by the magazine Women’s Own at about the same time, and when Carl was eleven he commissioned reincarnation researcher Nicholas McClean-Rice to interview him and his parents on his behalf. Stevenson decided to further investigate the case personally ten years later, conducting lengthy interviews in 1993 and a follow-up in 1998.

Later Development

Carl Edon’s case drew media attention from local papers and then internationally. His schoolmates began mercilessly teasing him about it, calling him a Nazi, which likely caused him to cease talking about the past life at around age ten or eleven (he said he was not interested and no longer remembered the details well).

At age sixteen, Carl joined the staff of British Rail. He fell in love with Michelle Robertson, and they had a child. In 1993, Stevenson judged that Carl, now twenty, had forgotten the past life entirely, although Carl did not explicitly say so.

In 1995, Carl was stabbed to death in an altercation with a co-worker at the railway, Gary Vinter, who had a history of violence. Vinter was sentenced to twelve years imprisonment, decreased to nine on appeal, then was sentenced to life in prison after murdering his wife. Michelle was pregnant with her second child by Edon, a girl she named Carla.6Dan (2020).

Attempts to Identify the Previous Incarnation

Carl’s uncle James Edon married the daughter of a German pilot killed in WWII, stimulating speculation that Carl might be his reincarnation. However the pilot’s widow did not believe in reincarnation and refused to provide any information that might verify this.

Other possible identities were suggested by a discovery made during pipeline excavations in Middlesborough in 1997. On 15 January 1942, a German Dornier 217E bomber had crashed near the town after hitting a balloon cable. The bodies of three of its crew, pilot Joachim Lehnis, bombardier Heinrich Richter and navigator Rudolph Matern, were found and buried shortly thereafter. The 1997 digging revealed the plane wreckage and the remains of the fourth crewman, radio operator Hans Maneke.

James and Valerie Edon became convinced that Carl had been the reincarnation of either Lehnis, the pilot, or Richter, whose corpse was found with one leg severed (though Stevenson later determined that the corpse with the severed leg was actually Maneke’s, as determined by insignia found with it).

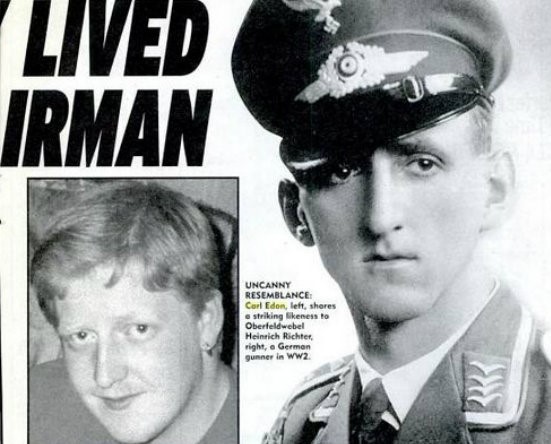

In 2013, local historian Bill Norman obtained a photograph of Richter taken shortly before his death, and a reporter for a local newspaper showed it to the Edons. ‘It’s got to be him,’ Valerie Edon is quoted as saying in the article. ‘The resemblance across the eyes and the nose is uncanny’.7Teesside Live (2002). This, together with the close proximity of the site of Carl’s murder to the area bombed by the plane before crashing, convinced the Edons that Carl had been Heinrich Richter. The news that the case was solved proliferated across the internet8Haraldsson & Matlock, 259-60. (for example, see this video).

Stevenson by contrast considered the case unsolved since Carl had remembered his plane being a Messerschmitt, not a Dornier, and his own name as Robert, not Joachim or Heinrich as the Dornier crew were named. Another crucial discrepancy was that Carl recalled his plane crashing into a window, not a balloon cable.

Reincarnation researcher James G Matlock pointed out that Richter is known not to have been the pilot, but the bombardier,9Haraldsson & Matlock, 260, Table 30-1. and that it is not known for certain that his leg was severed.

Both Stevenson and Matlock caution against facial features being used in a ‘diagnostic’ way in identifying cases, except in interethnic cases or unusual facial features such as birthmarks.10See Matlock (2019), 232, and Stevenson (1997), 1901-28.

In his report, Stevenson expresses regret for his delay in investigating:

This case, perhaps more than any other I have studied, shows the great importance of reaching a case when the subject is young and still talking about a previous life … The two delays – first in our learning about the case and second in not pursuing its investigation – may have caused the loss of much valuable detail. I particularly regret the loss of the sketches that Carl Edon made when he was between the ages of 2 and 4.11Stevenson (2003), 73-74.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Dan (2020). The musclebound murderer. Sublime True Crime [podcast transcript].

Haraldsson, E., & Matlock, J.G. (2016). I Saw a Light and Came Here: Children’s Experiences of Reincarnation. Hove, UK: White Crow Books.

Matlock, J.G. (2019). Signs of Reincarnation: Exploring Beliefs, Cases, and Theory. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Harrison, M., & Harrison, P. (2012). The Children that Time Forgot. Kindle Edition. [Originally published Life before Birth, UK, 1983: Futura Publications; republished as The Children That Time Forgot, UK, 1989: Sinclair Publishing.]

Stevenson, I. (1997). Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects. Volume 2: Birth Defects and Other Anomalies. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger.

Stevenson, I. (2003). European Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Teesside Live (2002). The uncanny case of Carl Edon. TeessideLive, 15 January. [Online newspaper. Last updated 22 July 2013.]