The phenomenon commonly known as dermo-optical perception (DOP) refers to the apparent ability to discern the colour of a stimulus object purely on the basis of touch, that is, without any visual access to the object. To the extent that one cannot literally ‘see’ with the fingertips the term perhaps is inapt. In part for this reason, the phenomenon also has variously been dubbed aphotic digital colour sensing, nonvisual colour perception, paroptic vision, cutaneous perception of colour, and eyeless sight;1Dermo-optical perception (2014). however, for convenience the popular term DOP will be used here.

This entry is a slightly revised version of a section of a paper by Irwin in the Australian Journal of Parapsychology and is reproduced here with the permission of the editor.2Irwin (2015).

History

Cases of apparent DOP have long been reported; for example, a case in the seventeenth century was described by the scientist Robert Boyle and by the novelist Jonathan Swift.3Brugger & Weiss (2008); Larner (2006).Indeed, in the mid-1960s Liddle noted that over fifty cases had been recorded in some 140 years and eight different countries4Liddle (1964), 24.. Apart from the pioneering work of Jules Romains5Romains (1920/1924), pseudonym of French poet and writer Louis Farigoule. the modern experimental study of DOP appears to date from the early 1960s.6For reviews see Berger & Berger (1991); Duplessis (1975); Gardner (1996/2003); Liddle (1964). A Russian woman, Rosa Kuleshova, was reported by a neuropathologist Dr Goldberg to be able to discern colours simply by ‘feeling’ them, and eventually she was tested formally by researchers in the Laboratory of Psychology at the Nizhny Tagil Pedagogical [teachers’ training] Institute7Novomeysky (n.d.). and later at the Biophysics Institute of the Soviet Academy in Moscow.8Ostrander & Schroeder (1970).

Accounts of these observations were reported in the popular press in the West, and soon many people came forward to assert that they, too, had the ability of DOP. Some of these claimants proved to be frauds and some subsequently confessed to fraudulent activity.9Keene (1976). Thus, there were some grounds for the assertion by the inveterate debunker Martin Gardner that ‘successful’ DOP performance could be attributed wholly to the experimenter’s use of poorly fitting blindfolds and a ‘peek down the nose’ by participants.10Gardner (1966). The generality of Gardner’s account nevertheless was vigorously challenged11Razran (1966); Youtz (1966). although sceptical commentators still cite Gardner’s explanation as definitive.12e.g., Nickell (2005).

Testing

Since the mid-1960s a number of people have been tested for DOP under increasingly rigorous experimental conditions. For example, participants have been screened from the coloured objects, allowed to touch them only through elasticised sleeves, and have had their head enclosed in a box. Notwithstanding some null findings,13e.g., Benski et al. (1998); Buckhout (1965); Shiah (2008). some participants have shown accurate tactile identification of colours well beyond that expected by chance.14e.g., Duplessis (1985); Duplessis & Novomeysky (1981); Jacobson, Frost & King (1966); Makous (1966); Nash (1971); Zavala, van Cott, Orr & Small (1967). On these grounds practical applications of DOP for blind people have even been mooted15e.g., Brugger & Weiss (2008); Duplessis (1975); Passini & Rainville (1992); Romains (1920/1924). but to date these proposals have not progressed substantially.

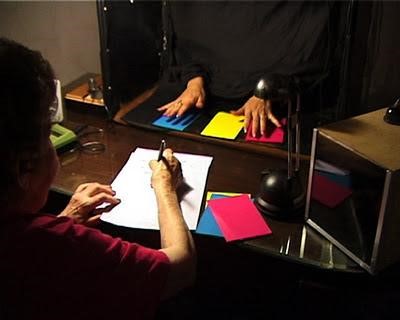

Figures 1 & 2: Experimental apparatus used in some studies by Duplessis (1975). Source: thegiarettas.blogspot.com.au. Copyright: Susan MacWilliam

Explanations

Although a growing number of psychologists now concede there is a phenomenon here to be explained,16Brugger & Weiss (2008). there remains a lack of consensus on the actual nature of DOP. Successful DOP performance has been observed even when participants are kept in complete darkness,17e.g., Duplessis & Novomeysky (1981); Youtz (1964). so it would seem the effect is not mediated by radiation within the normal visible spectrum.18But see Ivanov (1964). Some commentators19e.g., Kaiser (1983). have noted, however, that coloured objects may vary in their infra-red emissions and thus it is possible people may learn to use thermal sensors in the fingers to distinguish different colours by touch; indeed, some experimental evidence has been educed in support of this viewpoint.20Makous (1966).

A popular alternative view, according to Berger and Berger21Berger & Berger (1991), 103. is that the phenomenon has an extrasensory basis. The Bergers add, however, that an experiment by Nash22Nash (1971). appears to rule out an extrasensory account. In Nash’s study, DOP performance was significant when participants could touch the coloured stimulus card but not when the card was covered with a thick sheet of glass. Nash held that if esp was involved, performance would have been significant also in the plate-glass condition. This rejection of the extrasensory account nevertheless relies on a null result for its substantiation. Indeed, Nash’s findings may be accommodated under an appeal to some anomalous characteristic of experimental extrasensory perception (ESP) such as the parapsychological experimenter effect or the differential effect.23For general descriptions of these effects see Irwin & Watt (2007). Thus, the evidence against an extrasensory theory of the phenomenon is perhaps equivocal. In addition, DOP has also been found even when the target objects are enclosed in a cardboard or aluminium-foil envelope and the participants can only lay their hand above the envelope;24e.g., Duplessis & Novomeysky (1981). Despite these findings Duplessis herself preferred the infra-red explanation of DOP. for all practical purposes cardboard and aluminium would normally prevent the passage of infra-red radiation.25See West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd. (2017) on reflectivity of aluminium foil.

There are some grounds, therefore, for proposing that DOP is a paranormal phenomenon akin to ESP, and it may well be the case that the procedure of DOP tests is essentially psi-conducive, albeit to an exceptionally potent degree, it would seem.

Harvey J Irwin

Literature

Novomeysky, A.S. (n.d.). Abram S. Novomeysky. [Web page.]

Benski, C., Raphel, C., Stivalet, P., Cian, C., Esquivié, D., Buguet, A., Viret, J., & Masson, P. (1998). Testing new claims of dermo-optical perception. Skeptical Inquirer 22, 21-26.

Berger, A.S., & Berger, J. (1991). The Encyclopedia of Parapsychology and Psychical Research. New York: Paragon House.

Brugger, P., & Weiss, P.H. (2008). Dermo-optical perception: The non-synesthetic ‘palpability of colors’. A comment on Larner (2006). Journal of the History of the Neurosciences: Basic and Clinical Perspectives 17, 253-55.

Buckhout, R. (1965). The blind fingers. Perceptual and Motor Skills 20 191-94.

Wikipedia (10 August 2014). Dermo-optical perception. [Permanent Wikipedia entry.]

Duplessis, Y. (1975). The Paranormal Perception of Color. New York: Parapsychology Foundation.

Duplessis, Y. (1985). Dermo-optical sensitivity and perception: Its influence on human behavior. Biosocial Research 7, 76-93.

Duplessis, Y., & Novomeysky, A.S. (1981). The influence of invisible radiation of colored materials on human behavior and psychical activity. International Journal of Paraphysics 15/1 & 2), 3-19.

West Fraser Timber Co. Ltd. (2017). The physics of foil (May). [Downloadable PDF.]

Gardner, M. (1966). Dermo-optical perception: A peek down the nose. Science 151/3711, 654-57.

Gardner, M. (2003). Eyeless vision. In Are Universes Thicker than Blackberries?, 225-43. New York: Norton. [Originally published in 1996.]

Irwin, H.J. (2015). Thinking style and the formation of paranormal belief and disbelief. Australian Journal of Parapsychology 15, 121-39.

Irwin, H.J., & Watt, C.A. (2007). An Introduction to Parapsychology (5th ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina, USA.:McFarland.

Ivanov, A. (1964). Soviet experiments in ‘eye-less vision’. International Journal of Parapsychology 6/1, 1-23.

Jacobson, J.Z., Frost, B.J., & King, W.L. (1966). A case of dermooptical perception. Perceptual and Motor Skills 22, 515-20.

Kaiser, P.K. (1983). Nonvisual color perception: A critical review. Color Research and Application 8, 137-44.

Keene, M.L. (1976). The psychic mafia. New York: Dell.

Larner, A.J. (2006). A possible account of synaesthesia dating from the seventeenth century. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 15, 245-49.

Liddle, D. (1964). Fingertip sight: Fact or fiction? Discovery: Journal of Science 25/9, 22-26 & 49.

Makous, W.L. (1966). Cutaneous color sensitivity: Explanation and demonstration. Psychological Review 73, 280-94.

Nash, C.B. (1971). Cutaneous perception of color with a head box. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 65, 83-87.

Nickell, J. (2005). Second sight: The phenomenon of eyeless vision. Skeptical Inquirer 29/3, 18-20.

Ostrander, L., & Schroeder, S. (1970). Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall.

Passini, R., & Rainville, C. (1992). The dermo-optical perception of color as an information source for blind travelers. Perceptual and Motor Skills 75, 995-1010.

Razran, G. (1966). Dermo-optical perception of human extraocular color sensitivity: A clarification of current Soviet research and an article in Science. Soviet Psychology 5/1, 4-13.

Romains, J. (1924). Eyeless Sight: A Study of Extra-Retinal Vision and the Paroptic Sense. London: Putnam’s. [Originally published in French, 1920.]

Shiah, Y. (2008). The finger-reading effect with children: Two unsuccessful replications. Journal of Parapsychology 72/1, 109-32.

Youtz, R.P. (1964). Aphotic digital color sensing. American Psychologist 19, 734.

Youtz, R.P. (1966). Dermo-optical perception: Letter. Science 153 (20 May), 3725, 1108.

Zavala, A., van Cott, H.P., Orr, D.B., & Small, V.H. (1967). Human dermo-optical perception: Colors of objects and of projected light differentiated with fingers. Perceptual and Motor Skills 25, 525-42.