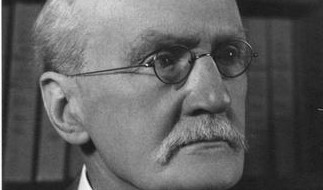

Gilbert Murray (1866–1957) was an Australian-born British classics scholar and translator, with strong political interests aligned to the Liberal party. He is significant in the literature of psychical research for his striking success in informal telepathy experiments, which are briefly described here.

Contents

Life and Career

George Gilbert Aimé Murray was born in Sydney, Australia. His family emigrated to England in 1877. He was educated at Merchant Taylors’ School and St John’s College, Oxford where he distinguished himself in Greek and Latin.

From 1889 to 1899 he was professor of Greek at the University of Glasgow. From 1908 he was Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Oxford. In 1925–1926 he was the Charles Eliot Norton Lecturer at Harvard University. He received honorary degrees from the universities of Glasgow, Birmingham and Oxford.

Murray was active in public affairs, holding the posts of vice-president of the League of Nations, president of the British Ethical Union, and first president of the general council of the United Nations Association. He refused a knighthood in 1912 but was appointed to the Order of Merit in 1941.

As an author, Murray is best known for his numerous translations of original Greek texts by Euripides and others, and for books about ancient Greece. He also publishedpamphlets about the League of Nations.

Murray joined the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in 1894, becoming a member of its governing council in 1906. He was president for the years 1915 and 1916 and again in 1952.

He was buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey on 5 July 1957.

Telepathy Experiments

Murray’s busy academic and public service activities left him little time for psychical research. However, in his spare time he carried out informal telepathy experiments with family members and friends, in which he showed remarkable aptitude.

Sources

Murray first described the experiments in an address to the SPR which was published in its Proceedings in 1915.1Murray (1916). It was followed in the same volume by a paper that described the experiments in detail, authored by Margaret Verrall, a Cambridge classics scholar, automatist and psychical researcher, who had been present at some of them.2Verrall (1916). A report by Eleanor Sidgwick, a leading SPR figure, was published in 1924.3Sidgwick (1924). Verrall’s daughter Helen Salter and her husband William Salter took part in experiments carried out while they were staying with the Murrays in 1931.4Salter (1941).Murray described further of his experiments in an address in 1952.5Murray (1952). An analysis of the later experiments was published by ER Dodds in 1972,6Dodds (1972). to which EJ Dingwall responded with a critique the following year;7Dingwall (1973). this in turn stimulated a response by Rosalind Heywood.8Heywood (1973).

Method

The experiments took place in the living room in Murray’s home, in the presence of family members and friends. The method was as follows. Murray left the room and the door was closed. One of the company, often Murray’s wife or eldest daughter, thought of a scene or incident and described it to the others present, one of whom took notes. Murray was called back into the room and described his mental impressions. Sometimes he held the hand of the person who had thought of the image, referred to as the ‘agent’, but this was not always the case and did not seem essential for success.

The selected imagery might be a memory or a fictional scene involving family members, friends or other people known to Murray; or a scene from a play or novel; or sometimes a mixture of these and other elements.Murray was often able to describe either all the key elements or some of the main ones. He was more often right than wrong, and was not often completely wrong, but frequently he could get nothing at all.

Examples of successful attempts:

1. Target: Alister and [Malcolm] MacDonald running along the platform at Liverpool Street, and trying to catch the train just going out.

Response: Something to do with a railway station. I should say it was rather a crowd at a big railway station, and two little boys running along in the crowd. I should guess Basil.9Verrall (1916), 70.

2. Target: Paul Sabatier walking with an alpenstock along a winding road in Savoy.

Response: A man like Mr. Irving going up a mountain – it isn’t Mr. Irving, it’s a clergyman with an alpenstock – should say it was a foreign clergyman.10Verrall (1916), 70.

3. Target: I think of Mrs. F. sitting on the deck, and Grandfather opening the door for her.

Response: This is Grandfather. I think it is on a ship, and I think he is bowing and smiling to somebody – opening the door.11Verrall (1916), 81.

4. Target: A scene in a book by Aksakoff, where the children are being taken to their grandparents, and the little boy sees his mother kneeling beside the sofa where his father is lying, lamenting at having to leave them.

Response: I should say this was Russian. I think it’s a book I haven’t read. Somebody’s remembrance of childhood or something. A family travelling, the children, father and mother. I should think they are going across the Volga. I don’t think I can get it more accurately. The children are watching their parents or seeing something about their parents. … I should think Aksakoff. They are going to see their grandmother.12Murray (1952), 165.

5. Target: I think [of] Diana of the Crossways. Diana walking up the road in the rain, and crouching down in front of the empty grate in the house.

Response: This is a book. Oh it’s Meredith. It’s Diana walking. I don’t remember the scene properly. Diana walking in the rain. I feel as if she was revisiting her house, but I can’t remember when it happens.13Sidgwick (1924), 216.

6. Target: I think of St Paul and the other man in prison and the fetters falling off.

Response: This feels totally different. Well, you’ve never given me anything like this before. I should say it was St Paul. But I do not get any words – not a quotation. I think he’s being tried or condemned. I think he’s a prisoner somehow. No, I can’t get it clear. Is he escaping from prison?14Dodds (1972), 376.

7. Target: Cleopatra’s needle being tugged along across the sea.

Response: Got a sort of splashing feeling – not the Boat-race and not the Bradford ship (the educational Bradford ship talked of during the evening). It’s rather like the Bradford ship dragging something behind – educational – a ship dragging something long and heavy. I’m clear about the thing. Oh, didn’t a ship bring Cleopatra’s needle, dragging it behind it?15Dodds (1972), 375.

8. Target: I think of Abraham Lincoln sitting in a hammock in California talking to Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford, smoking a long pipe.

Response: Grotesque too. Oh, it’s a sort of disgusting cinema thing – American. I don’t think a cinema. I think Charlie Chaplin and some cinema star – a woman – and they’re talking to some very distinguished person – Mr Wilson? – I should say it was talking to Uncle Sam or to some lean, tall, grey American.16Dodds (1972), 378.

9. Target: I get Lady Richards walking along the road in a grey mackintosh, rather blown about by the wind and the rain.

Response: Someone walking in the rain? Couldn’t be sure but I should think it was Lady Richards (because we met her this afternoon).17Dodds (1972), 379.

Results

The proportion of successes and partial successes was estimated to be 61% in sessions described by Verrall in 1916, 66% in sessions described by Sidgwick in 1924, and 70% in later sessions described by Dodds in 1974.18Dodds (1972), 395.

Analysis

Physical Contact

Physical contact with the agent (the person mentally holding the image that Murray was trying to guess) might have enabled Murray to note minute muscle movements, potentially giving positive or negative reactions to his statements. But contact was not always necessary for success, and given the complexity of his statements, any benefit in this case was considered to be negligible.19Verrall (1916), 65-66.

Arguments for Hyperesthaesia

The fact that the target image was generally spoken aloud, and that failure followed when this was not the case, suggested the possibility of hyperaesthesia – that Murray gained information about the target unconsciously by means of abnormally acute hearing. Further arguments cited in favour of hyperaesthesia included the fact that certain errors might have been caused by mishearing on Murray’s part, for instance ‘hall’ for ‘horse’ or ‘Mrs Carr’ for ‘Mrs Carlyle’. It was also noted that he was disturbed by loud noise, which might have disrupted his hearing senses.

Murray sometimes said he ‘heard’ a word, and the experiment in these cases was stopped. But in the circumstances it is not clear that he did actually hear the word spoken out loud, as opposed to mentally perceiving having done so.

The possibility of hyperaesthesia was raised by Murray himself in his first descriptions, apparently because he was diffident about his gift and willing to accept that it had a non-paranormal cause. Elsewhere he is quoted as saying, ‘It is a sort of joke that Nature has played on me … for I am by temperament and training as sceptical a person as you will find…. I don’t like these vague things!’and again, ‘I am naturally ashamed of it and keep it hidden as far as possible’.20Dodds (1972), 398. To another, he confided that ‘he had wished to avoid a reputation for doing “that sort of thing” since it might detract from any weight carried by his views on such vital matters as his work for the League of Nations.’21Heywood (1973) 125.

In their commentaries, Verrall, Salter, Sidgwick and Dodds all doubted that hyperaesthesia was the underlying cause. In later life, Salter writes, Murray was persuaded by objections to it and ‘admitted that the source of his knowledge seemed to be mainly telepathic, though telepathy might make use of real sights, sounds, smells, memories, to reach its goal.’22Salter (1957), 155-56.

Among serious commentators, only EJ Dingwall argued for hyperaesthesia, on the grounds that not enough was known about it and that the descriptions of the experiments were too imprecise for it to be ruled out.23Dingwall (1973). Dingwall in turn was challenged by Rosalind Heywood, an SPR member who, from her real life experience as a telepathic experient, contested his assumptions about what should and should not be the case if telepathy was real.24Heywood (1973).

Arguments for Telepathy

Discussions over the choice of image were said to be carried out in low voices that could not be expected to carry through a closed door. Salter and her husband tested this, finding that a person standing three yards from the closed door could hear nothing that was said inside the room unless it was spoken well above conversational level.In at least one successful session, Murray during his absence was in a room that was separated by another room from the one in which the experiments were taking place.25Dodds (1972), 400.

The fact that Murray was disturbed by loud noises, it was argued, might as well mean that his psychic faculty was disrupted as that it prevented him ‘overhearing’ the target image being spoken. Dodds also questioned why Murray’s success rate did not diminish with age, as would be expected if it was based on acute hearing, but rather increased (he was still getting successes aged eighty), and why it made little difference who was acting as the principal agent, despite the wide range of pitch, volume and carrying power that this would have occasioned .26Dodds (1972), 399.

A striking characteristic of Murray’s responses was that they often began by feeling the general atmosphere of the scene, not with concrete details that would be expected if he had overheard particular words.In his later paper he commented:

Of course the personal impression of the percipient himself is by no means conclusive evidence, but I feel there is one almost universal quality in these guesses of mine which does suit telepathy and does not suit any other explanation. They always begin with a vague emotional quality or atmosphere: “This is horrible, this is grotesque, this is full of anxiety” ; or rarely, “This is something delightful”; or sometimes, “This is out of a book”, “this is a Russian novel”, or the like. That seems like a direct impression of some human mind. Even in the failures this feeling of atmosphere often gets through. That is, it was not so much an act of cognition, or a piece of information that was transferred to me, but rather a feeling or an emotion; and it is notable that I never had any success in guessing mere cards or numbers, or any subject that was not in some way interesting or amusing.27Murray (1952), 163.

With regard to errors that might have been caused by mishearing, Verrall found 17 such cases, arguing that ‘the number is not large nor the evidence striking’28Verrall (1916), 75. when compared to 45 cases where Murray appeared to have perceived the whole arrangement and was not influenced by words used by the agent.

Another indication of telepathy over hyperaesthesia was that on some occasions Murray showed awareness of the agent’s unspoken thoughts, also of actions carrried out during his absence by people in the room.29Dodds (1972), 401.He sometimes gave details that were part of the agent’s mental image, but which he or she had not included in the verbal description spoken aloud, and which he could not have known by normal means, suggesting that telepathy was operating at least partly.30Verrall (1916), 79-81.

Dodds concluded that

taken as a whole, Murray’s results cannot be convincingly or completely explained without postulating telepathy. If anyone chooses to assume that hyperaesthesia also played some part, I cannot prove him wrong. But I question whether much is gained by introducing a second causal factor almost as mysterious, and as undefined in its limits, as telepathy itself.31Dodds (1972), 402.

Melvyn Willin and Robert McLuhan

Literature

Anon. (1917). Gilbert Murray and telepathy (1917). Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 9/3, 129-32.

Dingwall, E.J. (1973). Gilbert Murray’s experiments: Telepathy or hyperaesthesia? Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 56, 21-39.

Dodds, E.R. (1972). Gilbert Murray’s last experiments. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 55, 371-402.

Heywood, R. (1973). Correspondence. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 47, 124-27.

Murray, G. (1916). Presidential address. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 29, 46-63.

Murray, G. (1952). Presidential address. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 49, 155-69.

Salter, H. (1941). Experiments in telepathy with Dr Gilbert Murray. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 32, 29-38.

Salter, H. (1957). Obituary: Gilbert Murray. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 39, 155-56.

Sidgwick, Mrs. H. (1924). Report on further experiments in thought-transference carried out by Professor Gilbert Murray, LL.D, Litt.D. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 34, 212-74.

Sidgwick, E. (1924). Appendix II. To Mrs. Sidgwick’s paper on Professor Murray’s experiments on thought-transference. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 34, 336-41.

Verrall, M. (1916). Report on a series of experiments in “guessing”. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 29, 64-110.