In this case of responsive xenoglossy, an American woman was regressed under hypnosis to a past life as a ninteenth-century German woman, and spoke in imperfect but comprehensible German, a language which she had never learned.

Contents

The Regression Experiment

Carroll Jay, an American Methodist minister, took an interest in hypnosis and used it for pain relief. In the late 1960s he started to experiment with past-life regression. On 10 May 1970, he hypnotized his wife, Dolores Jay, to try to relieve a backache. During the session, he asked her if her back hurt, and was surprised to hear her answer ‘no’ in German (‘nein’) rather than English, in an apparent display of xenoglossy.

Three days later he hypnotized her again to see whether a German-speaking personality might emerge. She now spoke in German, identifying herself as ‘Gretchen’, and in sessions over the following months gave many more details about herself in the same language.

Carroll Jay did not speak German and used elementary teaching books in order to understand these statements. He also engaged with friends who understood the language, including one native speaker. However, ‘Gretchen’ understood at least simple English and would answer in German questions posed to her in English.

The sessions were recorded on tape, though some were lost before the case was investigated.

Reincarnation research pioneer Ian Stevenson heard about the case in the summer of 1971, and visited the Jays at their home in Mount Orab, Ohio, USA in early September. While Dolores Jay was regressed, Stevenson held a conversation with her in German, as also did a German-speaking journalist. Stevenson further arranged for German academics to speak with her over the following two years.

To verify that Dolores had not come by her knowledge of German in a normal way, Stevenson travelled to Clarksburg, West Virginia, where she and her husband had spent their early lives, and interviewed nineteen people with relevant knowledge. He also consulted with a local historian on the settlement of German-speaking immigrants in the area, and determined with certainty that German instruction was not available in schools Dolores had attended. Researching Dolores’s ancestry, he turned up some German ancestors who had all died before she was born.

In 1974, a lie-detector test confirmed that Dolores sincerely believed she had not acquired her knowledge of German in a normal way. She also visited the University of Virginia’s Division of Parapsychology laboratory, where she had further conversations in German while regressed. However, she then declined to undergo further experimentation due to fatigue and criticism by the family’s Christian community.

Stevenson estimated his time interviewing the Jays at about 25 hours. With the help of an assistant, he transcribed and translated nineteen taped regression sessions, resulting in 346 pages of transcript. The couple also provided a forty-word German passage Dolores Jay had written while in an altered state.

Because Stevenson was unable to identify the previous person by use of historic records, he published the case as one of responsive xenoglossy rather than reincarnation, and included it in his book Unlearned Languages: New Studies in Xenoglossy.1Stevenson (1984), 70-71, 169-203. All information in this article is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted.

Carroll Jay published a book on the case in 1977.2Jay (1977).

Gretchen’s Life

The personality identified herself as Gretchen Gottlieb. She further stated that she lived in Eberswalde, Germany, with her father Hermann Gottlieb, the mayor of the town, who had white hair. The family had a day-time housekeeper named either Frau Schilder or Schiller, who had four children. Gretchen’s mother, Erika, had died when Gretchen was eight, and she had no brothers or sisters. They lived in a stone house on a street named Birkenstrasse. The town had a college, church, butcher shop and bakery.

Gretchen further stated that she had brown hair and either blue or green eyes, wore a brown dress and helped the housekeeper take care of her children, the youngest of whom was three. She did not attend school, and seemed to have little background knowledge, being unable to name a large city nearby (Berlin is just 45 kilometres from Eberswalde), or the nearest large river, or the current head of state. She was sure that the pope’s name was Leo, and spoke negatively of Martin Luther, holding him responsible for religious strife in the area (she was Catholic); she frequently expressed worry about being overheard talking by authorities.

Gretchen would not shift to an age older than sixteen when requested to, suggesting that she probably died at about that age. She gave conflicting accounts of the cause, sometimes referring to an illness, other times suggesting it happened during a period of imprisonment.

Certain details suggested to Stevenson that Gretchen had lived in Germany in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. She used German words not in common usage until then, notably Bundesrat, a ruling body in German states from 1867. A political struggle had taken place between the government and the Catholic Church in the 1870s – the strife that Gretchen was apparently referring to – and Leo XIII became pope in 1878.

However, independent efforts by Stevenson and a journalist failed to discover any traces of a historical Gretchen. Mayoral records for Eberswalde showed there had never been a mayor named Hermann Gottlieb, a birth record for a Gretchen Gottlieb could not be found, and there is no street named Birkenstrasse in Eberswalde. Stevenson considered other possibilities: that Gretchen had been illegitimate and given a different surname; that she lived in a different town named Eberswalde; or that she had actually lived in Eberstadt, which matched the geographical details more closely. But none of these leads proved fruitful.

James Matlock notes that Carroll Jay’s interpretation of Gretchen’s geographical statements differs from Stevenson’s, in part because of a later regression in which she mentioned a town named Heppenheim. If Eberswalde referred to a region rather than a town, Matlock suggested, she could have been saying Burgenstrasse rather than Birkenstrasse, as Heppenheim has a street of this name. A Bundesrat was formed in Heppenheim in 1848 and figured in the Catholic-Protestant political strife at that time, which would place Gretchen’s life somewhat earlier that Stevenson believed. Matlock writes: ‘I do not know what reason Stevenson may have had for ignoring this information but, if accepted, it would mean that Gretchen was a great deal more accurate in her statements than Stevenson portrays’.3Matlock (1987), 100 n5.

Xenoglossic German

Stevenson and two native German speakers who spoke with Gretchen attested that her German was responsive: she could answer questions and carry on conversations. However her speech contained grammatical errors, and attempts to broaden the topic beyond what she said spontaneously generally failed. One native German noticed a heavy accent and statements that did not entirely make sense. When Stevenson analyzed this session, he found that she made eight pertinent responses for every one inappropriate one when asked questions in English; when asked questions in German the ratio was twelve to seven.

Gretchen mostly spoke only in response to questions, and would sometimes take a long time to do so, occasionally answering after the next question had been asked (Stevenson attributed this to her deep hypnotic state). When she did speak spontaneously, it was usually about how dangerous it was to talk, since the Bundesrat might be listening, or about the religious struggle that scared her.

Her fluency fluctuated from session to session. The total number of German words she uttered before anyone used them while speaking to her was 237; half of these she uttered before any German at all was spoken to her. She never spoke grammatically-correct sentences longer than five words, or any sentences longer than seven. They were generally in the present tense and of primitive construction; sometimes the word order was wrong or words were omitted.

Her pronunciation ranged from satisfactory to excellent, in Stevenson’s estimation, and she would sometimes firmly correct others’ mispronunciations or misinterpretations. Some words were pronounced in an American English accent, but generally she pronounced words as a German speaker would, ruling out the possibility that she had learned German only by reading it.

Dreams and Spontaneous Emergences

More than a year before Gretchen’s first appearance, Dolores Jay had a dream which she later felt must refer to Gretchen. She saw a girl wearing a long dress with a lace front, riding sidesaddle on a horse, with an older man who was on foot. An angry crowd attacked them with sticks and stones, and while the man escaped, one of the crowd grabbed the horse’s bridle, at which point Dolores awoke. She began the dream as a spectator to the scene, but by the end of it was experiencing it from the point of view of the girl.

During the winter of 1971–72, Dolores experienced nightmares in which she saw Gretchen beckoning to her, inviting her to join her on another plane of existence. She also sensed Gretchen’s presence during the day, feeling that if she turned around she would see her. Dolores recounted that while she found these experiences frightening, she was never frightened by Gretchen as a person, feeling she was friendly but in distress.

Two years later, when Gretchen emerged spontaneously, she described a vision of a small girl taken by her father to a strange city where a man was addressing a crowd in front of a church. A policeman on horseback arrested the speaker and dispersed the crowd, including the girl and her father, who fled. When asked who the girl was, Dolores answered ‘it was me’, but without mentioning the name Gretchen.

German Writing

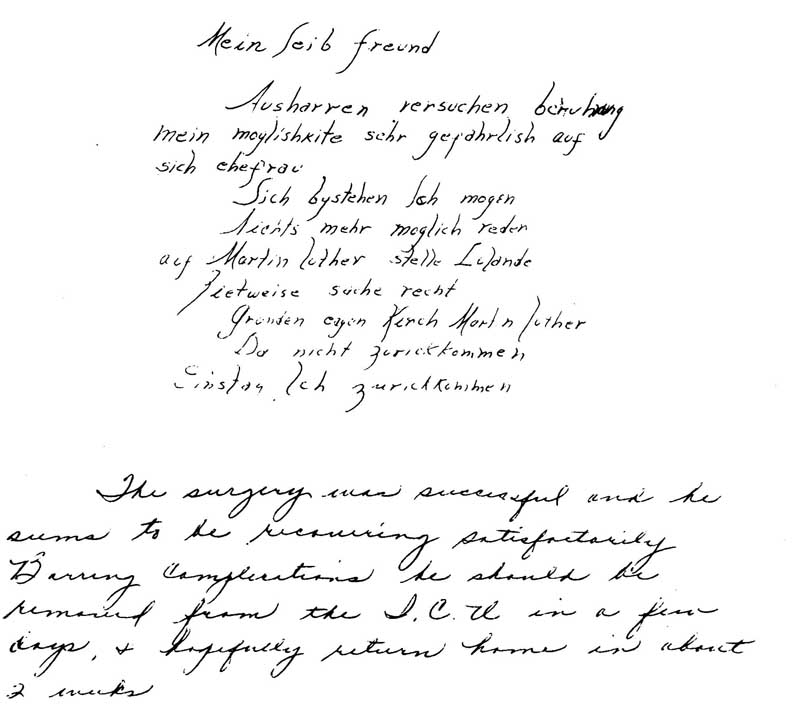

Dolores Jay wrote a few words in German in the early stages of a session in April 1971. Before she’d been regressed to the Gretchen personality she seemed to stare at something, and when her husband asked her what she was seeing, she replied, ‘a girl’. At this point he was called out of the room and in his absence Dolores spoke 39 words in German, which were picked up by the tape recorder. When he returned, Dolores said Gretchen wanted her to write, and, reluctantly, she attempted it: she wrote forty German words, almost the same as those that had earlier been recorded. The meaning is unclear. The passage shows a mix of German words spelled as if an English speaker were spelling them phonetically, and German words spelled correctly, as if the writer knew how to write in German. The letters were separate, unlike Dolores’s usual cursive handwriting.

Fig. 1: Gretchen’s German script, and a sample of Dolores Jay’s handwriting made during her normal waking state.4Reproduced in Stevenson (1984), 43.

Criticism and Controversy

Stevenson formed the view that the Gretchen personality referred to a past life of Dolores Jay. He held that skill in speaking a language responsively cannot be transferred from one person to another either psychically or through normal means, but only acquired through practice. However, because he could not identify the previous person he presented the case as evidence of responsive xenoglossy and postmortem survival rather than as evidence of reincarnation per se.

Controversy followed the publication of a detailed account of the case in the 20 January 1975 Washington Post, which was based on interviews with Carroll Jay. Some criticized Jay for having sought out publicity, accusing him of having faked the case for commercial gain. Stevenson denied this, claiming that Jay’s motivations for approaching the media were to counteract accusations from his Christian community that he was ‘consorting with the devil’ and to make a public contribution to parapsychology.

Some critics dismissed the case as fraudulent, without providing substantive arguments.5Rogo (1985), 227. Others acknowledged Stevenson’s painstaking efforts to rule out fraud, but contested his claim that this was a case of genuine xenoglossy. Linguist Sarah G Thomason focuses on the weakness of Gretchen’s German: she describes the vocabulary as ‘minute’ and the pronunciation ‘spotty’, referring to Gretchen’s anglicized mispronunciations of the German words blau (blue) and schön (beautiful) as examples, and noting her use of the Germanized English word ‘schicken’ for ‘chicken’.6Thomason (1995).

Gretchen’s answers to questions, Thomason states, are ‘largely confined to utterances of one or two words, and many of them are simply repetitions of the interviewer’s question’. Thomason characterizes Gretchen’s writing as containing ‘spelling errors that one might expect from an English speaker who had learned only a little German’.7Thomason (1995), 5-6. She points out that Gretchen seemed to speak German better than she understood it, which is inconsistent with the normal tendency for people to understand a non-native language better than they speak it.

Thomason also likens what she calls ‘Gretchen’s anachronistic concerns about religious persecution’ to historically-inaccurate statements from a separate regression case by another hypnotist.8Thomason (1995), 12. However, she does not mention that Gretchen’s declared Catholicism, her use of terms introduced into German by certain dates, and her mention of a pope named Leo all fit well with a time period in which Catholics were being persecuted in Germany.

Thomason further attributes Dolores Jay’s apparent German knowledge to ‘the subject’s ability to use clues in the conversational context to make educated guesses about the interviewer’s intent’ as well as the fact that many of the exchanges involved yes-or-no questions about facts which only the subject could know and are therefore impossible to judge for accuracy, or involved her repeating back questions.9Thomason (1995), 14.

In a letter responding to criticisms, Stevenson writes: ‘Almost anyone might pick up casually a little German, but not the amount – small as it was – that Gretchen knew’.10Stevenson (1987).

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Jay, C.E. (1977). Gretchen, I Am. New York: Wyden Books.

Matlock, J.G. (1987). Review of Unlearned Languages: New Studies in Xenoglossy by I. Stevenson. Journal of Parapsychology 51, 99-103.

Rogo, D.S. (1985). The Search For Yesterday: A Critical Examination of the Evidence for Reincarnation. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall.

Stevenson, I. (1984). Unlearned Languages: New Studies in Xenoglossy. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1987), Letter to the editor, Journal of Parapsychology 51, 373.

Thomason, S.G. (1995). Xenoglossy. [Web Page.]