The legendary stage magician and escape artist Harry Houdini (1874–1926) was hostile to spiritualism, and wrote books about his debunking of mediums.

Life

Harry Houdini was the stage name of Erik Weisz, a Hungarian-American. He was born 24 March 1874 in Budapest, according to his birth certificate; however, he later claimed he was conceived in Budapest and born in Appleton, Wisconsin, USA. His father, a rabbi, brought the family from Hungary to America. His stage name was derived from the French magician Jean-Eugene Robert-Houdin.1Encyclopedia Britannica (2018). All information in the section is drawn from this source except whether otherwise noted.

Houdini became a trapeze performer at an early age, then performed in vaudeville shows after his family moved to New York City. From about 1900 he began to gain fame as an escape artist, combining great physical strength and agility with lock-picking skills. For instance, he was able to extricate himself from chains and shackles in a water-filled box suspended upside-down far above ground.

Houdini died on 31 October 1926 of peritonitis following acute appendicitis, which was possibly caused by multiple blows to his abdomen taken as part of a performance in the preceding days.2Kalush & Sloman (2006), 510-15.

Exposing Spiritualism

In his book A Magician Among the Spirits (1924) Houdini states that he was always interested in spiritualism and that in his early career he held fake sittings. He was aware that he was deceiving his clients but considered it ‘a lark’. Later, following a bereavement, he wrote, ‘I was chagrined that I should ever have been guilty of such frivolity and for the first time realized that it bordered on crime’.3Houdini (1924a), xi.

Houdini was convinced that spirits could not manifest in the physical world, based on many associates having promised him they’d send him a signal from beyond after their deaths, but none doing so. He noted that grieving people would desperately seize on any evidence, making them easily susceptible to fraud. ‘I have watched this great wave of Spiritualism sweep the world in recent months,’ he writes, ‘and realized that it has taken such a hold on persons of a neurotic temperament, especially those suffering from bereavement, that it has become a menace to health and sanity’.4Houdini (1924a), xvi. Houdini claimed to have attended hundreds of sittings and read all spiritualist literature extant at the time.

In A Magician Among the Spirits, Houdini discusses techniques for fraudulently producing messages via slates, raps, table levitation and spirit photographs. He devotes a chapter to ectoplasm, concentrating on the medium Marthe Béraud (Eva C); his opinion was that the purportedly-spiritual substance was produced by mediums using illusionists’ techniques similar to those used in his own frequently-performed ‘Hindoo needle trick’, in which he would apparently swallow as many as 200 needles and a great length of thread, then regurgitate the needles, all threaded.

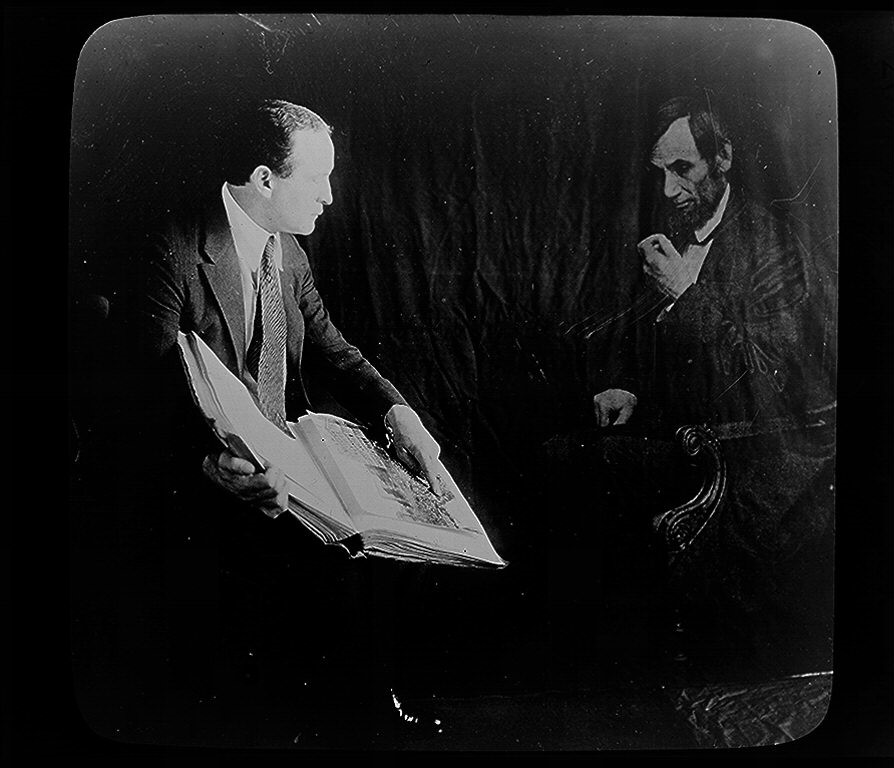

Fig 1: To demonstrate the use of double exposure to create fake ‘spirit photographs’, Houdini had himself photographed with the apparent ghost of Abraham Lincoln.5American Memory (n.d.).

Another chapter describes crimes involving spiritualism culled from newspaper reports, such as wealthy widows being told by ‘spirits’ to leave their fortunes to mediums. In one episode, he describes a man murdering two of his sons in the belief that his dead wife had communicated asking him to send her children to her. Houdini also blamed the 1881 assassination of US president James Garfield on spiritualism, alleging that the assassin claimed to have been inspired by spirits.

Mina ‘Margery’ Crandon

In the same year as the publication of A Magician Among the Spirits, Houdini published a short book6Houdini (1924b). in which he claimed to have exposed the American medium Mina Crandon, known as Margery. She had accepted a challenge by the magazine Scientific American, which offered a prize of $2,500 to any medium who could convince a committee of investigators of the genuineness of his or her gifts. The committee was composed of William McDougall, Daniel F Comstock, Walter Franklin Prince, Hereward Carrington and Houdini.

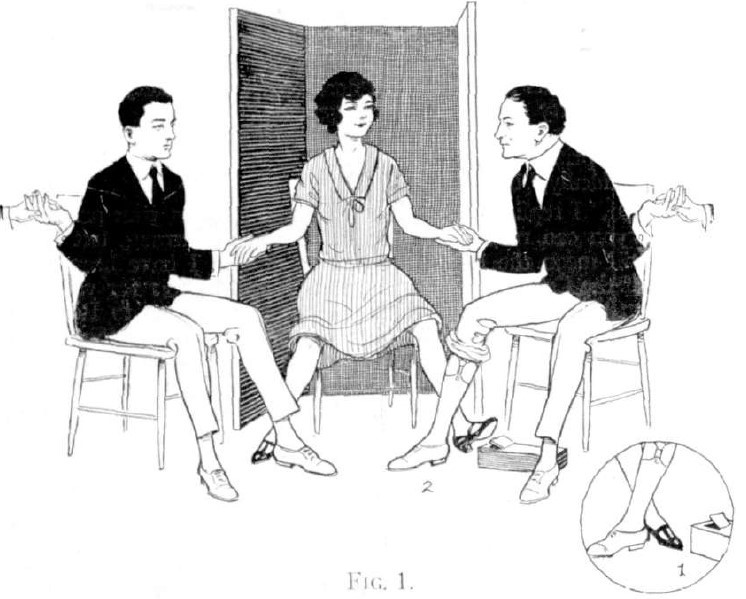

Houdini participated in a sitting in which ‘spirits’ rang an electric bell contained in a box. He sat to Margery’s left, holding her hand, his calf touching hers, and in this position claimed he felt her use her foot to operate the box. At a second sitting he attributed a table levitation to the medium leveraging it with her head. He then persuaded the medium to sit in a cabinet of his devising; a collapsible ruler was later found there which he claimed she used to operate the bell box. She in turn accused him of having placed there himself.

Fig 2: Illustration from A Magician Among the Spirits. Margery is pictured in the centre, Houdini on the right (her left). According to him, even while their calves touch, she is able to operate the bell-box with her foot7Houdini (1924b), 6, Fig 1..

Criticisms

An unattributed review of A Magician Among the Spirits in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research notes that two pages of errata and addendum had been added to the book, and adds that a further two pages could easily have been compiled, as the text was riddled with misspellings and factual errors.8Anon (1924). For instance, Houdini attributed exposes of mediums to investigators who in fact never met with them. The review also takes issue with Houdini’s claim that an (unnamed) English doctor estimated that spiritualism had caused a million cases of insanity.9Whether the putative doctor meant a million cases in England or worldwide, Houdini does not specify. See Houdini (1924a), 189.

Houdini carried on a friendly relationship for some years with the author Arthur Conan Doyle, a devout spiritualist, despite their diametrically-opposed views. Eventually the two became disillusioned with each other, however. Doyle wrote, ‘The unmasking of false mediums is our urgent duty, but when we are told that, in spite of our own evidence and that of three generations of mankind, there are no real ones, we lose interest, for we know that we are speaking to an ignorant man’.10Doyle (1927). All information in this and the following three paragraphs are drawn from this source. Doyle attributed Houdini’s stance in part to a desire for publicity, as the public had a keen interest in spiritualism.

Doyle also offered a different version of what happened at the ‘exposure’ of Margery, based, by his own account, on notes taken at the sittings. At the first sitting, the entranced medium’s ‘control’, named Walter, suddenly cried ‘You have put something to stop the bell ringing, Houdini, you—!’ Lights were raised and the rubber from the end of a pencil was found stuck in the angle of the bell-box’s wooden flap. Doyle argued that only Houdini had a deft enough touch to place it, and noted that this had never occurred when the magician was not present.

Doyle’s account of the ruler in the cabinet matches Houdini’s but adds an observation by another sitter that Houdini was seen ‘without any apparent reason to pass his hand along the lady’s arm, and so into the box’, presumably to place the folding ruler inside.

Houdini maintained unwaveringly that his illusions and escapes were all accomplished through normal magicians’ methods. However, according to Doyle, Houdini once told him that ‘a voice which was independent of his own reason or judgment told him what to do and how to do it’, apparently ensuring his safety. Once when he jumped without waiting for word from the voice he almost broke his neck. ‘This was the nearest admission that I ever had from him that I was right in thinking that there was a psychic element which was essential to every one of his feats,’ Doyle wrote.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

American Memory (n.d.). The American variety stage: Vaudeville and popular entertainment, 1870–1920: Houdini and the ghost of Abraham Lincoln. [Webpage.]

Anon. (1924). Review of A Magician Among the Spirits by Houdini. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 21, 339-40.

Doyle, A.C. (1927). Houdini the enigma. Strand Magazine (August and September).

Encyclopedia Britannica (2018). Harry Houdini, American Magician. [Web page.]

Houdini, H. (1924a). A Magician Among the Spirits. New York, London: Harper & Brothers.

Houdini, H. (1924b). Houdini Exposes the Tricks Used by the Boston Medium ‘Margery’. New York: Adams Press Publishers.

Kalush, W., & Sloman, L. (2006). The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America’s First Superhero. New York: Simon & Schuster, Atria.