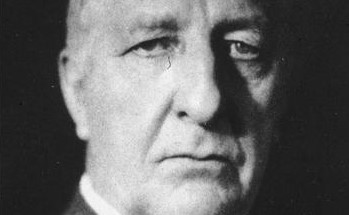

William McDougall (1871–1938) was an eminent British psychologist who during appointments at American universities contributed largely to the establishing of parapsychology as an experimental science.

Early Life

William McDougall was born in Chadderton in Lancashire in 1871,the son of a prosperous manufacturing chemist and inventor, Isaac Shimwell McDougall, and his wife Rebekah, née Smalley.1Greenwood & Smith (1997). Aged five he was sent to a private school and at fourteen to a Real-Gymnasium in Weimar. At fifteen he entered the University of Manchester, from which he graduated with first-class honours, specializing in geology in his last year. In 1890, he was told by his father he could attend Cambridge University if he won a scholarship2McDougall (1930), 196. and did so, attaining his BA in 1894, amd MB, BChir and MA in 1897, specializing in physiology and human anatomy with physiology.

McDougall lost his mother to cancer in his freshman year, an event to which he later attributed the loss of ‘any remaining orthodox belief in a beneficent Providence’, as well as a change of interest from geology to medicine.3McDougall (1930), 196-7. He credited William James’s Principles of Psychology with showing him that the study of human nature should be approached from two sides, ‘from below upwards by way of physiology and neurology, and from above downwards by way of psychology, philosophy, and the various human sciences’.4McDougall (1930), 200.

In 1899, rather than pursue a career as a doctor, he travelled with the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to the Torres Straits, then left the group to join Dr Charles Hose in Borneo to study the head-hunting tribes.5McDougall (1930), 201. This led to the publication of a co-authored authoritative work in 1912.6McDougall (1930), 202.

Returning to Cambridge, he abandoned field anthropology to take up his ‘original scheme of direct attack on the secrets of human nature’.7McDougall (1930), 203. He married Anne Hickmore, of whom he wrote, ‘I have learned more psychology from her intuitive understanding of persons than from any, perhaps all, of the great authors’.8McDougall (1930), 204.

The couple spent their first year of marriage in Göttingen, Germany, where McDougall carried out intensive laboratory work on colour vision, inspired by lectures on special-sense physiology from his undergraduate year. The couple had five children, one of whom died young of rheumatic fever.

Career

Returning to England in 1900, McDougall turned his attic into a laboratory and spent four years in experimental research, mostly on vision. At this time he became interested in psychical research, joining the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) and reviewing books on the topic.9McDougall (1930), 205. All information in this section is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted. In 1904, he was appointed to the Wilde Readership in Mental Philosophy at Oxford, a light teaching post which enabled him to engage in further research in psychology, although the subject ‘had no recognized place in the curricula and examinations’ at the time.10McDougall (1930), 207. During this period he wrote two important books, Social Psychology (1908) and Body and Mind (1911). He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1912.

During World War I McDougall served as a medical officer with the Royal Army Medical Corps, treating shell-shocked soldiers. In 1920, he accepted an invitation to fill the chair of psychology of Harvard University. He said he was ‘attracted by the way America seemed to experiment, to act, to put things through on a large scale’;11McDougall (1930), 212. He may also have been encouraged by the university’s openness to parapsychology.12Berger (1988), 117. At Harvard he began a twenty-year and 49-generation experiment on rats in a bid to find evidence for the Lamarckian view of organic evolution (this failed partly because of criticisms of methodological defects). In 1927, he accepted a position as head of the psychology department of the new Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, a position he held for the rest of his life.

McDougall died in 1938 of the same cancer that had taken his mother, completing his last book while bedridden.

Parapsychology

McDougall wrote: ‘Whenever I have found a theory widely accepted in the scientific world, and especially when it has acquired something of the nature of a popular dogma among scientists, I have found myself repelled into skepticism.’ 13McDougall (1930), 204. This stance led him to reject behaviourism, the dominant model of academic psychology at the time, in favour of unorthodox lines of inquiry, at some cost to his professional reputation. He opposed materialism and wrote in support of an animistic view of nature.

These views predisposed McDougall to an interest in the study of psychic phenomena, then dominated by the British SPR and American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR). He was sceptical of physical mediumship, having attended three sittings in which he believed fraud was employed; in one instance hegrabbed a ‘spirit’ by the head to discover the medium’s body attached. In 1922, he headed an investigation of the physical mediumship of Mina Crandon (‘Margery’), sponsored by the magazine Scientific American, becoming convinced it was fraudulent. He was also somewhat hostile to spiritualism for converting what he felt should be a science into a religion.

McDougall’s preference was for experimental study and he participated in telepathy experiments.14Berger (1988), 116. All information in this section is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted. He served on the council of the SPR, serving as president for two years. At Harvard, he reactivated the university’s neglected Richard Hodgson Memorial Fund for parapsychological research, to the benefit of fellow psychologist Gardner Murphy, who used its resources to study telepathy.

McDougall was elected president of the ASPR in 1920, but was dismissed three years later by its board, which was dominated by spiritualists and supporters of Margery. McDougall then helped found the Boston Society for Psychical Research together with other psychical researchers opposed to the ASPR’s direction.

Possibly in reaction to these events, McDougall advocated for parapsychological study to be carried out in universities rather than by groups of lay enthusiasts.15Pratt (1970), 388. In fact, several universities at this time started to offer courses.16See Berger (1988), 126. In 1923, he took on JB Rhine and Louisa Rhine as students, and his sponsorship subsequently led to Rhine taking up a permanent post as head of the Parapsychological Laboratory at Duke University. The two became co-editors of the new Journal of Parapsychology in 1937, and McDougall wrote an editorial for its first issue.17McDougall (1937).

Selected Writings

A book-length bibliography18Robinson, A.L & Duke University Press (1943). compiled by Anthony Lewin Robinson can be accessed here.

The case of Sally Beauchamp (1907). Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 19, 410-31. (See article on Christine Beauchamp.)

In memory of William James (1911) . Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 25, 11-29.

Body and Mind: A History and a Defence of Animism (1911) . London, Methuen; New York, Macmillan. (Contains a chapter on parapsychology.)

Presidential address (1920). Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 31, 105-23.

The need for psychical research( 1922). Harvard Graduates’ Magazine 31, 34-43.

The need for psychical research (1923). Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 17, 4-14.

Further observations on the Margery case (1925). Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 19, 297-308.

The ‘Margery’ mediumship (1926). Psyche 7, 15-30.

Psychical research as a university study( 1927) . In The Case For and Against Psychical Belief, ed. by C. Murchison, 149-62. Worcester, Massachusetts, USA: Clark University Press,

Foreword. In Extra-Sensory Perception (1934), ed. by J.B. Rhine. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Boston Society for Psychic Research.

Editorial Introduction (1937). Journal of Parapsychology 1, 1-9.

Explorer of the Mind: Studies in Psychical Research (1967). Comp. and ed. by R. Van Over & L. Oteri in collaboration with A. McDougall. New York: Helix Press.

Collection

A collection of McDougall’s papers is held at Duke University, dating mostly from the period of his tenure there. The approximately 10,000 items include correspondence, manuscripts, research, teaching materials, clippings, notebooks, photographs, diaries, drawings, and tributes. As well as his work in mainstream psychology, it covers his interest and work in parapsychology and the Parapsychology Laboratory.19Duke University Libraries (n.d.).

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Berger, A.S. (1988). Portrait of William McDougall. In Lives and Letters in American Parapsychology: A Biographical History, 1850–1987, 108-32. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Duke University Libraries (n.d.). Guide to the William McDougall Papers, 1892-1982. [Web page.]

Feather, S.R., & Ensrud, B. (2018). JB Rhine. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]

Greenwood, M., & Smith, M. (1997). William McDougall, 1871-1938. [Published online on the Royal Society website.]

McDougall, W. (1930). William McDougall. In A History of Psychology in Autobiography, vol. 1, ed. by C. Murchison, 191-223. New York: Russell and Russell.

McDougall, W. (1937). Editorial introduction. Journal of Parapsychology 1/1, 1-9.

Pratt, J.G. (1970). William McDougall and present-day psychical research. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 64 ,385-403.

Richmond, K. (1939). William McDougall, 1871–1938. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 45, 191-5.

Robinson, A.L., & Duke University Press (1943). William McDougall, M.B., D.Sc., F.R.S.: A Bibliography: Together With a Brief Outline of His Life. Durham, North Carolina, USA.: Duke University Press.