Christine Beauchamp (pseudonym) was the subject of a case of dissociative identity (multiple personality) disorder reported in 1906 by Morton Prince, an American physician and psychologist. The episode has been much discussed and is often compared to the similar case of Doris Fischer reported by Walter Prince.

Contents

Background and Life

Morton Prince was careful to keep secret the identity of his famous patient ‘Miss Beauchamp’, whose first name was sometimes given as ‘Christine’ and sometimes as ‘Sally’. Psycho-archaeologist Saul Rosenzweig was able to identify her through his research in the 1980s as Clara Ellen Fowler, born in Beverly, Massachusetts, USA, on 20 January 1873.1Rosenzweig (1988), 45.

In his detailed case report,2Prince (1906). All information in this article is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted. Prince notes her unsettled family background: Beauchamp’s father had a violent temper, her parents were unhappily married and her mother made it clear she disliked her daughter. When she was thirteen, her mother died. A series of emotional traumas over the next three years, which Rosenzweig attributes to likely severe abuse by her father,3Rosenzweig (1987), 5. caused her to flee her home permanently at sixteen. Prince refers to numerous ‘nervous shocks’ but without specifics, to avoid revealing his patient’s identity.

Beauchamp’s first dissociation produced the alter best known as Sally Beauchamp. According to Rosenzweig, this coincided with the death of her four-days-old brother Charles on 7 June 1880, when she herself was seven. Another newborn sibling, Bessie, died when she was thirteen. Rosenzweig speculates that Beauchamp blamed herself for being somehow complicit in their deaths.

Disorder and Treatment

As a child Beauchamp was nervous, sickly, absorbed in daydreams and subject to somnambulism and trance states. In 1898, she came to Prince seeking relief from physical symptoms that included headaches, bodily pains, insomnia and exhaustion – symptoms he terms ‘neurasthenic’ in the terminology of the era. At this time, aged 23, she had become too weak to continue her work as a nurse in a children’s home and hospital.4Rosenzweig (1988), 46. She was studying at a New England college, where she was well-regarded as a bright and diligent student by teachers and friends, and said to be an avid reader. However, they had now begun to notice her swift changes in mood and character.

Morton found Miss Beauchamp, or B1 as he refers to her in his code for her alters, to be refined, well-educated, well-read, highly conscientious, restless, sometimes lost in abstractions or fixed ideas, inclined to bear ill treatment in silence and sometimes unable to do what she wished. She was reluctant to discuss herself or her circumstances, or even the symptoms for which she sought treatment.

Prince began using hypnotic suggestion to ease her pain. While under hypnosis, an entirely different personality emerged, whom he refers to as ‘Sally’, or ‘B III’. (‘B II’ was less a personality than a hypnotic state discovered early in the case, with a strong set of memories of Beauchamp’s life.) Sally was vivacious, bold and assertive, and talked like a rebellious child, resisting all efforts to control her. She also exhibited hostile feelings about the real Beauchamp, calling her ‘stupid’ and complaining that she went around mooning with her head in a book. At this early stage Sally was numb, unable to feel even pricks or burns. Her eyes were closed and she continually rubbed them, complaining it was unfair that Beauchamp could see and she could not.

In June Beauchamp was hospitalized. As Sally, she managed at last to open her eyes and since she showed none of Beauchamp’s symptoms was allowed to leave the hospital, even making plans to travel to Europe before Prince was able to bring out the real Beauchamp again.

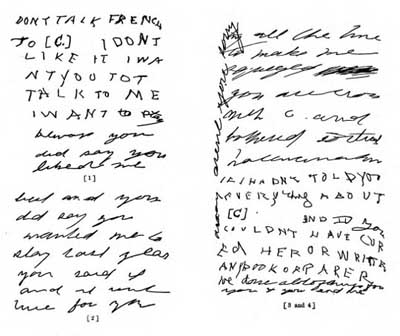

Sally now began tormenting Beauchamp: she left abusive letters to read after Beauchamp regained control, forced her to tell lies, tore up her homework and unraveled her knitting, and arranged visits that Beauchamp would then have to honour. No efforts by Prince were able to stop this.

On 7 June 1899, the patient asked Prince to come to her home. At first she was unable to speak for nervousness, but then suddenly changed: she chatted pleasantly and seemed healthy-minded. However, she now insisted that Prince was not Prince but her friend William Jones, and that he had entered through a window. Prince realized he was witnessing the birth of a new personality, whom he designated ‘B IV’. Later it was revealed that in 1893, Beauchamp had been shocked when, during a thunderstorm, Jones had come to the hospital where she then worked, and entered via a window as a prank.

B IV had memories of life up until the year 1893; the next six years were missing. However, she attempted to conceal this, gradually learning incidents in this period from Prince and other associates. She was not aware of the other alters, and was angry at being spoken to familiarly by people who to her were strangers. Because she seemed healthier in mind than Beauchamp, Prince wondered if she might be the true Christine Beauchamp. However she tended to be angry and selfish. Now haunted by two alters, one of whom (Sally) was free spending, Beauchamp got a job as a waitress in New York City, but was unable to sustain it due to the antics of Sally and B IV. So she pawned her watch (later redeemed by Prince) and returned to Boston, where she attempted suicide by closing the windows and turning on the gas. This was only prevented by the emergence of Sally, who turned the gas off.

On the theory that B IV was the original personality, Prince turned to trying to eliminate B I, repeatedly giving her hypnotic suggestions to transform or merge into B IV. When that failed, he accepted that the true Christine Beauchamp was B I and B IV in combination, along with B II, who could only be awakened by hypnosis and had the most complete set of memories.

From a written description of her early life by Sally, Prince learned about traumas Beauchamp suffered at age thirteen. Her mother was diagnosed with a terminal disease, which Beauchamp felt was her fault for not loving her enough and for dreaming instead of acting. Also, she blamed herself for the death of her newborn sister, who at this time was kept in a separate room: while Beauchamp held her to quiet her crying, the baby suddenly stopped breathing and died soon after.

In the spring of 1901, Prince attempted to reintegrate B I and B IV, an effort strongly resisted by Sally and B IV. The alters intensified their war against each other, with B IV trying to kill Sally, and Sally causing B IV to cut her arms. Sally decided to die, made a will and buried a box of her papers.

In January 1902, B II emerged in hypnosis and, when told to awaken with all her memories intact, did so, knowing her whole life except the periods of Sally’s control. Now the patient was physically well, enjoyed peaceful sleep, was without hallucinations, impulses, obsessions, and even abnormal suggestibility. From then on, the genuine Beauchamp (who seemed to be a combination of B I, BII and B IV) experienced extended periods of full control, Sally emerging only in times of stress.

Prince’s case report concludes with a description of a six-month period when the genuine Beauchamp was integrated and in control.

Samples of Sally’s writing5Prince (1906), Appendix Q, 561.

Prince’s Publications

Prince published a short preliminary report of the Beauchamp case in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research (PSPR) in 1901, while treatment was still in process. He had already decided – apparently following Frederic WH Myers – that Sally, since she dated from so early in childhood, represented the patient’s subliminal mind,6Prince (1901), 472. and that a combination of B I, B II and B IV was the true Beauchamp.7Prince (1901), 482.

In 1906 the full case report followed and became a sensation: it went through two editions and many printings, and was the basis of many theatrical productions, one of which became a Broadway hit.8Leys (2000), 44.

Little is known about Clara Ellen Fowler following the termination of her treatment by Prince, except that she went on to marry one of his assistants.9Aldridge-Morris (1989), 5.

Parapsychological Commentary

William McDougall, in a paper published in PSPR in 1907, notes that the phenomenon of multiple personality was known in the late nineteenth century, listing several published cases prior to Beauchamp’s. He contrasts the materialist view, that the ‘disintegration’ occurs in the brain, with the dualistic view that the soul, mind or psyche, being the seat of individuality, is what splits in multiple personality cases. He notes that Sally was a fully-developed personality possessing an independent mental life from the time Beauchamp was learning to walk, and also that she appeared not to be included in the merging of personalities that Prince reports was the cure, but rather ceased to exist. From this he speculates that she was an independent psyche communicating telepathically with the divided portions of Beauchamp’s psyche.10McDougall (1907).

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Aldridge-Morris, Ray (1989). Multiple Personality: An Exercise in Deception. Hove and London, UK, and Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc.

Leys, R. (2000). Trauma: A Genealogy. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

McDougall, W. (1907). The case of Sally Beauchamp. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 19, 410-31.

Prince, M. (1901). The development and genealogy of the Misses Beauchamp: A preliminary report of a case of multiple personality. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 15, 466-83.

Prince, M. (1906). The Dissociation of a Personality: A Biographical Study in Abnormal Psychology. New York: Longmans, Green & Co.

Rosenzweig, S. (1987). Sally Beauchamp’s career: A psychoarchaeological key to Morton Prince’s classic case of multiple personality. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs 113/1, 5-60.

Rosenzweig, S. (1988). The identity and idiodynamics of the multiple personality “Sally Beauchamp”: A confirmatory supplement. American Psychologist 43/1, 45-8.