Many people consider the notion of karma to be an inherent element of reincarnation, or even its main purpose. However, not all reincarnationist cultures believe that our actions in one life are punished or rewarded in another, while analysis of credible reincarnation cases shows no convincing evidence for karma.

Contents

Terminology

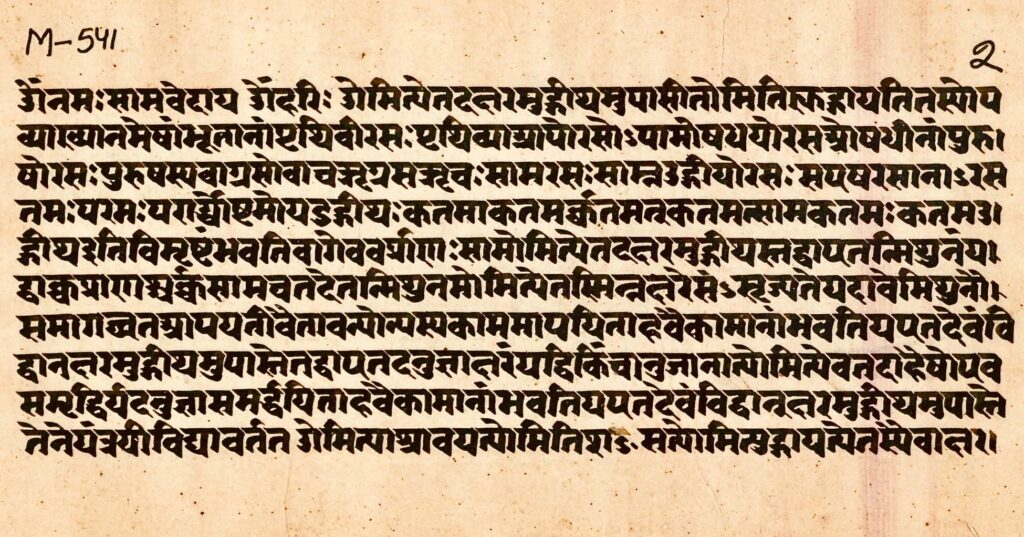

A formal definition of karma is ‘(in Hinduism and Buddhism) the sum of a person’s actions in this and previous states of existence, viewed as deciding their fate in future existences’.1Lexico entry. (Sikhism and Jainism also maintain the belief and it has spread to some degree to the West; see below.) The word ‘karma’ comes from Sanskrit, meaning ‘action, effect, fate’.

Separate Origins of Reincarnation Belief and Karmic Belief

Because India is so well-known for its cultural adherence to reincarnation, belief in it is often said to have originated there.2See for instance, Alexakis (2001); Flood (1996), 86.However, a significant and diverse number of tribal cultures worldwide believe in reincarnation, as explored in the early reincarnation scholarship of anthropologist and reincarnation researcher James Matlock.

Matlock used an anthropological database of sixty cultures selected from different culture clusters, making them statistically independent of each other.3See Matlock (1993, 1995). He found that tribal cultures from all over the world believe in reincarnation, maintain social customs related to it, and observe the same features, which are also those found by researchers today in modern cases: children’s past-life memories, birthmarks related to past-life injuries, behavioural carryovers and announcing dreams. He notes an axiom of anthropology that the more widespread a cultural trait, the more ancient its origin, and argues that the origin of worldwide reincarnation belief lies in the observation of its manifestations.4Matlock (2019), 60-63.

Matlock also notes that reincarnation beliefs outside the Indic religions do not include karma:5Matlock (2019), 38. in ancient Greece, for instance, the philosopher Plato wrote that punishment for bad deeds happened between lives, not in subsequent ones.6See Matlock (2019), 68. The father of reincarnation research, Ian Stevenson, gives modern examples: the Druze sect of Islam holds that God assigns people lives, emphasizing variety in circumstances, though God might reward a kind act in one life with fortunate circumstances in the next; ultimately, an individual’s entire series of lives is evaluated on a final judgment day.7Stevenson (1980), 5-6. The Tlingit and other reincarnationist tribes of the Pacific Northwest see no connection between moral actions in one life and circumstances in the next, nor do the reincarnationist tribes of West Africa.8Stevenson (2001), 38-39.

The first known mention of karma occurs in the ancient Indian texts known as the Upanishads, composed around 600 BCE, which also contain the first known clear mention of reincarnation. The Chandogya Upanishad states: ‘Those whose conduct has been good will quickly obtain some good birth. … But those whose conduct has been evil will quickly attain an evil birth, the birth of a dog, or a hog, or a Kandala’ [Untouchable, the lowest of the Indian castes].9Book 5.10.7, translator unknown. From Hinduism, the idea was embraced by Buddhism and spread throughout the East.

Karmic Belief in the English-speaking World

The importance of belief in karma in the English-speaking world is not to be underestimated. In 2018, a survey by the Pew Research Center found that 33% of Americans, including 29% of American Christians, believe in reincarnation,10Gecewicz (2018). and because it is so often accompanied by belief in karma, that belief must be only somewhat less common.

In 1875, the Theosophical Society was founded in New York by occultist and philosopher Helena Blavatsky and she published a book explaining her worldview in 1877, Isis Unveiled: A Master-Key to the Mysteries of Ancient and Modern Science and Theology. Blavatsky drew heavily on Indic thought and embraced Indic notions of reincarnation and karma entwined.11See Blavatsky (1889a, 1889b). Blavatsky’s notion of karma had more of an ‘eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth’ ethic than the Hindu or Buddhist version, however, punishing people with physical suffering in subsequent lives corresponding closely to what they had inflicted. Due to this difference, Stevenson followed Blavatsky herself in labelling it retributive karma.12For a summary of Blavatsky’s reincarnation views, see Matlock (2019), 78-80. Theosophy’s popularity in the West has made it a major influence on Western ideas about reincarnation.

Belief in karma was furthered by American psychic Edgar Cayce, whose work was formative for the New Age movement. For about half of his forty-year career Cayce provided medical readings only, and that remained his priority for the second half; however, after being introduced to esoteric topics (including Theosophy) by a client, he began giving ‘life readings’, totalling more than 2,500. J Gordon Melton in his analysis of the life readings found markers of Theosophy,13Melton (1994). as did Matlock, noting that the frequent appearances of ancient Egypt and Atlantis matched Blavatsky’s version of human history, and the lengths of the intermissions between lives that Cayce assigned his client echoed her ideas also.14Matlock (2019), 82. Even the suggestion given to the entranced Cayce to prompt a life reading implies karma, as it includes the line, ‘Also the former appearances in the earth’s plane, giving time, place, name and that in that life which built or retarded the development of the entity’.

Criticisms of Karmic Belief

Belief in karma has been criticized for discouraging sympathy towards those who are suffering – since they must have done something previously to deserve it – or even justifying the inflicting of harm. In 1999, the England soccer team coach Glenn Hoddle caused a public scandal by declaring that people born with disabilities were being punished by the sins of a previous life.15Arlidge & Wintour (1999). Actress Shirley MacLaine triggered uproar by writing in her 2015 autobiography:

What if most Holocaust victims were balancing their karma from ages before, when they were Roman soldiers putting Christians to death, the Crusaders who murdered millions in the name of Christianity, soldiers with Hannibal, or those who stormed across the Near East with Alexander? The energy of killing is endless and will be experienced by the killer and the killee.16MacLaine (2013), 241.

In defence of karma in this case, Arvind Sharma notes that Indic thought generally discusses karma on an individual basis, though there is some discussion of communal karma. He cites one ancient medical text’s discussion of epidemics, in which the actions of ‘corrupt leaders’ are said to incur bad karma on a whole population: ‘the deities forsake the community; the seasons, the winds, and waters are disturbed, and the population devastated’.17Caraka Samhita 3.3.13 and 3.3.19, cited by Sharma (2015), 360 n3.

The population of ‘Untouchables’, the lowest of the hereditary castes in India’s caste system, is now approximately two hundred million, but its members continue to be exploited for cheap labour, physically attacked, denied access to education, employment and running water, and even murdered.18Chaudhary (2019). But Hinduism itself traditionally enshrines justification for such ill treatment:

Untouchability as a religiously legitimated practice attached to certain hereditary Indian castes was well established by 100 B.C. Hindu religious texts rationalized untouchability with reference to karma and rebirth; one was born into an Untouchable caste because of the accumulation of heinous sins in previous births.19Joshi (1983).

However, untouchability as a component of karma is not substantiated by evidence.

Ian Stevenson noted that karma can be used by its believers as a way of avoiding responsibility in their current lives for their fate: it is the predestined result of the malfeasance of a past incarnation and thus cannot be avoided or overcome. Nor does karma do any better a job of keeping humans honest than in Western views of afterlife reward/punishment, an Indian monk cited by Stevenson argues:

We in India know that reincarnation occurs, but it makes no difference. Here in India we have just as many rogues and villains as you have in the West.20Stevenson (2001), 232.

Investigated Cases and Karma

Stevenson is clear in his assessment of the evidence for karma found in reincarnation cases he investigated:

I have found almost no evidence of the effects of moral conduct in one life on the external circumstances of another.21Stevenson (2001), 251.

For instance, he adds, in cases showing a decrease in socioeconomic level from one life to the next, no pattern of wrongdoing on the part of the previous incarnation has emerged.

In a handful of recorded reincarnation cases, the subject felt that karma might have been at play. They include:

- Ma Tin Aung Myo, who conjectured that she had been changed from man to woman as punishment for misbehaviour of some kind; this however was a typical Burmese explanation for the ‘demotion’ and also a contradiction of her earlier statement that it had happened because the previous incarnation had been shot in the groin.22See Matlock (2019), 160.

- Bishen Chand Kapoor, who attributed his steep drop in socioeconomic level to having gotten away with murder in his previous life.23Stevenson (2001), 251-52.

- Wijeratne Hami, who blamed the stuntedness of his right arm and hand on his having murdered his fiancée in his previous life with that hand after she spurned him, but maintained until later in life that he had acted correctly; Matlock notes that there is no evidence that this happened due to an external force rather than psychosomatic processes.24See Matlock (2019), 160.

- Ma Khin Ma Gi, who attributed defects in her arm and leg to having hunted and mistreated animals in her previous life,25Stevenson (1997), 2000-7. to which Matlock makes the same argument.26See Matlock (2019), 160.

- Rani Saxena, who thought that ‘God had put her in the body of a woman’ because in her previous life as a male lawyer she had ‘selfishly exploited women.’27Stevenson (2001), 188.

However, these cases are very few among hundreds published in which no mention of karma was made by other subjects, and, as Stevenson states, their attribution to karma by the subjects ‘may amount to nothing more than a rationalization of the differences’.28Stevenson (2001), 252.

Matlock notes, in relation to the phenomenon of birthmarks corresponding to injuries suffered by a previous incarnation, and other carryover pain and illness, that researchers have gathered a vast body of evidence that the victim rather than the perpetrator continues to suffer from harm inflicted.29Matlock (2019), 159-60. He observes that neither do involuntary memories of the intermission between lives provide evidence for karma: subjects frequently recall choices about future lives made freely by the soul alone, or with the advice of a spiritual entity who is apparently unconstrained by karma. Matlock points out that this refutes the argument of karma adherents that investigated cases reveal only the life immediately previous, while karma can be delayed for many lives: the soul should still not have free choice.30Matlock (2019), 173.

Reframing karma as an hypothesis, reincarnation researcher Jim B Tucker used Stevenson’s database of cases to test it, attempting to correlate five traits in previous incarnations (saintliness, criminality, tendency to moral transgression, philanthropy and religious observance) with three measures of current-life good fortune (wealth, social status and, in Indian cases, caste). The only correlation was found to be between ‘saintliness’ and ‘degree of wealth’, which Tucker suspects, being isolated, was a statistical anomaly.31Tucker (2008), 221-22.

Stevenson, Matlock and Tucker all emphasize that while good actions are not necessarily rewarded, or bad actions punished, there certainly is psychological continuity across lives. A central category of signs sought by researchers is behavioural memories: correspondences of behaviour between subjects and previous incarnations. These can be skills, habits, preferences, interests, aversions, mannerisms, posture, retained cultural or religious customs, phobias, attachments, sex roles, language, post-traumatic stress disorder and others. Thus, both choices and harms suffered in past lives can influence the current life by simply persisting into it. In a nod to Western notions of karma that incorporate these carryovers, Matlock introduced the term ‘processual karma’:

It would make sense that we would see signs of such ‘processual karma’ if what passes from life to life is a continuous stream of consciousness which is duplex in its nature because the subconscious would preserve the memory, behavioral dispositions, elements of personality, and so on, that comprise a person’s identity.32Matlock (2019), 189.

However, this phenomenon differs entirely from retributive or, to use Matlock’s term, ‘juridical karma’, in that it can be caused by harms suffered as well as choices, and it requires no external force to occur, only natural psychological processes.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Alexakis, A. (2001). Was there life beyond the life beyond? Byzantine ideas on reincarnation and final restoration. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 55, 155-77.

Arlidge, J., & Wintour, P. (1999). Hoddle’s future in doubt after disabled slur. Guardian (30 January).

Blavatsky, H.P. (1889a). The Key to Theosophy. New York: Theosophical Publishing Company.

Blavatsky, H.P. (1889b). Thoughts on karma and reincarnation. Lucifer 4/20 (April), 89-99. [Reprinted in H.P. Blavatsky, Collected Writings, vol. 11, 136-46.]

Chaudhary, A. (2019). India’s caste system (Bloomberg QuickTake). Washington Post (8 October).

Flood, G.D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Joshi, B. (1983.) India’s Untouchables. Cultural Survival (September).

MacLaine, S. (2013). What if… A Lifetime of Questions, Speculations, Reasonable Guesses and a Few Things I Know For Sure. New York: Atria.

Matlock, J.G. (2019). Signs of Reincarnation: Exploring Beliefs, Cases, and Theory. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Matlock, J.G. (1995). Death symbolism in matrilineal societies: A replication study. Cross-Cultural Research 29, 158-77.

Matlock, J.G. (1993). A Cross-Cultural Study of Reincarnation Ideologies and Their Social Correlates. [MA thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York.]

Melton, J.G. (1994). Edgar Cayce and reincarnation: Past life readings as religious symbology. Syzygy: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture 3/1.

Gecewicz, C. (2018). ‘New Age’ beliefs common among both religious and nonreligious Americans. [Web post, Pew Research Center, Fact Tank: News in the Numbers].

Sharma, A. (2015). The Holocaust: An Indic perspective. In The Value of the Particular: Lessons from Judaism and the Modern Jewish Experience. Supplements to The Journal of Jewish Thought and Philosophy 25, 359-76.

Stevenson, I. (2001). Children Who Remember Previous Lives: A Question of Reincarnation (rev. ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Stevenson, I. (1997). Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects. Vol. II: Birth Defects and Other Anomalies. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger.

Stevenson, I. (1980). Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Vol. III: Twelve Cases in Lebanon and Turkey. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.

Tucker, J.B. (2008). Life Before Life: Children’s Memories of Previous Lives. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.