Stefan Ossowiecki (1877–1944), a businessman by profession, was also a psychic whose clairvoyant abilities made him famous in his native Poland. He became known internationally as a result of numerous successful experiments with Polish, French and British psychical researchers.

Contents

Life and Career

Stefan Ossowiecki was born in 1877 in Moscow. His father was a wealthy chemical manufacturer who in his youth had been assistant to Dmitri Mendeleev, inventor of the Periodic Table of elements. Both parents’ families were landed gentry in what had been the eastern part of Poland. This had ceased to exist as a state at the end of the eighteenth century when it was partitioned between Russia, Prussia and Austria. Poles were under pressure to assimilate to the occupying cultures, with restrictions on educational and industrial development in the occupied areas. Prospects for a career development for a talented engineer and inventor such as Stefan’s father naturally led to the centres of industrial power in Russia. By the time of Stefan’s birth the family had links to the highest circles: his brother-in-law Jan Jacyna taught military subjects to the children of Grand Duke Michael, brother of Tsar Nicholas II.1Jacyna (1926).

Ossowiecki’s childhood, education and early career followed a pattern predictable for a youngster born into a wealthy family with influential connections. At the age of 17 he graduated from the exclusive Third Cadet Corps in Moscow and went on to study at the St Petersburg Institute of Technology. During the early years of the twentieth century he was busy managing factories and serving on the boards of various enterprises. He became head of the family business after his father’s death in 1914.

Despite their successful integration into Russian society, the Ossowieckis never lost their sense of Polish identity. Stefan became actively involved in working for Poland’s independence at a time when Russia was being shaken by war and revolution. At the end of 1918, as member of the Polish Military Committee, he was arrested on suspicion of working with the French, imprisoned under terrible conditions for six months and sentenced to death. He was taken to a place of execution, only to be saved at the last moment by the intervention of a friend from his student days who had become a high ranking official in the new regime.2Geley (1927), 33

Psychic Abilities

According to a memoir published by Ossowiecki in 1933, he became aware of psychic abilities around the age 14. He relates how, during the diploma exam at the Institute, he was able to obtain a clairvoyant preview of his chemistry questions through a sealed envelope and passed with flying colours. He also states that in his youth he was capable of enormous psychokinetic feats.

As a twenty-year-old student on work experience, he met an elderly Jewish Kabbalist named Vorobey, who taught him how to develop his gift, training him to focus and visualize. His abilities may have been further deepened by the experience of arrest, isolation and the threat of death. In a newspaper interview in 1937 he said he saw this as a watershed in his spiritual and psychic development.3Goniec Warszawski, 29 April 1937, 6.

In 1918, having lost all his property, Ossowiecki followed friends and family members to Poland, which had now regained its independence. His brother-in-law became a general in the Polish army and served as adjutant to the head of state. In Warsaw, Ossowiecki again found himself moving in the most influential circles. He resumed his business activities, becoming involved in a number of enterprises. His career as a psychic took off, and he worked with psychical researchers from Poland and abroad. It is no exaggeration to say that he was one of the most famous people in Poland during the years between the wars.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Ossowiecki and his wife remained in Warsaw, not expecting the conflict to last as long or to be as horrific as it turned out to be.4Letter from Marian Świda, Ossowiecki’s stepson, to Alexander Imich, personal archive. Throughout those years, he helped great numbers of people who visited from all over the country in the hope that he could clairvoyantly trace missing loved ones. This activity is mostly unrecorded, and would not in any case have evidential value, as he admitted lying when his visions of their fate were too distressing to relate.

Ossowiecki was married twice but died childless in 1914. He was a victim of the massacres carried out by the Nazis in the early days of August 1944, soon after the start of the Warsaw uprising.5A number of sources relay the same biographical information in varying detail, among them: Barrington et al; Boruń & Boruń-Jagodzińska; Bugaj; Geley; Ossowiecki; Polski Słownik Biograficzny (1979), 431-33.

Personality and Beliefs

Accounts ofOssowiecki describe him as extraverted, sociable and trusting, always amazed when someone revealed their ugly side. He loved a good joke, good food, good wine, and the company and admiration of ladies.His fame as a psychic made him even more popular.

His first marriage failed, and his wife left him for someone else. This was a shock to Ossowiecki, but was no surprise to those who knew the couple: that a clairvoyant should be unable to predict such an important event in his own life was cause of amusement (he always said that he was ‘blind’ in relation to himself and those close to him).

His second marriage, in 1939 to Zofia Skibińska, was a great success. It is thanks to her that accounts of some of the most important later cases of Ossowiecki’s psychic gifts were preserved and disseminated to scholars abroad.6Grzymała-Siedlecki (1962), 278-94.

In his autobiography, Ossowiecki devotes considerable space to explaining his worldview, based on the ideas of Hoene-Wroński, a nineteenth-century Polish philosopher.Hoene-Wroński saw creation as ‘constant movement between the Absolute and the concrete, as mankind strives for harmony and freedom’7Barrington et al. (2005), 16. in its attempt to evolve into higher states of being and finally to rejoin the Absolute, or One Soul. In this, humanity is helped by individuals with special gifts, such as great artists or scientists, as well as true psychics.8Ossowiecki (1933/1976), 71-73.

Holding such views, it is hardly surprising that Ossowiecki never used his psychic abilities for financial gain or personal betterment. Instead, he preferred to help people in practical ways. He also regarded it as his mission to show the way to a higher level of spiritual development.He was also proud of his powers and enjoyed the adulation they brought, but at the same time he felt humbled by them.

Sources

Experiments with Ossowiecki were carried out by French researchers Gustave Geley and Charles Richet during 1921-24 and published contemporaneously in the Revue Metapsychique shortly after they took place, as well as in book form.9Geley (1927). Reports by another French researcher, Eugene Osty, and by Polish researchers10Articles in periodicals such as Zagadnienia Metapsychiczne, publication of the Polish Society for Psychical Research, and Ilustrowany Kurier Codzienny, a regular supplement to a daily paper. were published contemporaneously. Two experiments by British researchers were published in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research (see below).11Dingwall (1924), Besterman (1933).

In Poland, stories of spectacular feats by Ossowiecki abound, including visions of future and past events, the identification of murderers and saving famous people from disasters. Some are confirmed by reliable sources, but many other accounts are too poorly documented to be considered evidential; these include spontaneous diagnoses of medical conditions, seeing auras, bilocation and the ability to influence people at a distance.

A World in a Grain of Sand, an English-language study of his life and work published in 2005, discusses in detail only those experiments and cases which were reported first-hand, verified, and corroborated by reliable witness accounts; unconfirmed cases are included in an appendix.12Barrington et al. (2005), 165-74. Ossowiecki’s autobiography also contains accounts of experiments and real-life cases backed and corroborated by witness reports.

After his death, verifiable accounts of real-life cases were sent to his widow in response to her appeal, and these were included in an expanded edition of his autobiography published in Chicago in 1976 thanks to the efforts of Ossowiecki’s stepson, Marian Świda.13Ossowiecki (1933/1976).

Corroborated Cases

Some of Ossowiecki’s reported real-life cases involved locating missing objects or persons by means of psychometry, handling an object associated with the target, the background of which was unknown at the time of the reading. In one such case that was corroborated by witnesses, engineering students at Warsaw Polytechnic approached Ossowiecki for help tracing missing cash books. They gave him letters from individuals who might be suspected of taking the books. Ossowiecki did not visit the place but described it in detail. Following his instructions the students located the books, which had been torn up and thrown behind some filing cabinets. As was his practice, he declined to name the actual culprit, however.14Barrington et al. (2005), 107-108.

Experiments

Most of the experiments involved identifying the contents of concealed writing or drawings (usually in sealed envelopes), also occasionally photos and packages containing objects. A notable feature was Ossowiecki’s ability to describe, along with the hidden target itself, its concealed wrappings and their history, for instance the provenance of the box that contained the target object and the person who bought the cotton wool in which the object was wrapped.15Barrington et al. (2005), 71-72.

The experiments had well-defined objectives and procedures, being thoroughly recorded and employing a variety of targets and shielding. Most were completely or partially successful. Some targets were drawn on the spur of the moment, but many were prepared in advance far away by strangers and shielded in layers of envelopes. Ingenious variations were employed, for instance writing in invisible ink16Barrington et al. (2005), 55-57. and a drawing shielded in a sealed lead pipe.17Barrington et al. (2005), 34-35. As well as simple drawings, targets were sometimes sophisticated quotations or intentionally unusual images, such as an elephant having its trunk bitten off by a crocodile (this was devised by Geley and successfully identified by Ossowiecki).18Barrington et al. (2005), 34.

SPR Warsaw Experiments

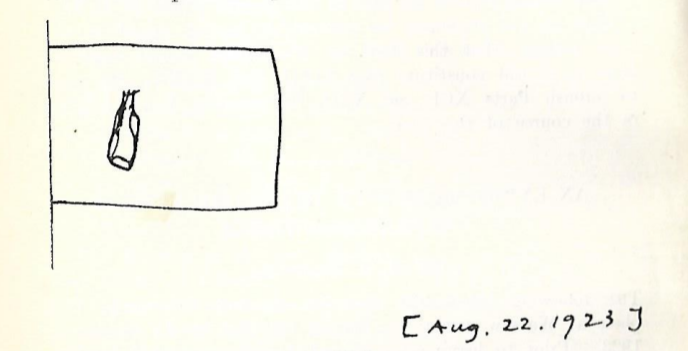

An experiment carried out during the 1923 International Conference of Psychical Research in Warsaw stands out as representative of Ossowiecki’s abilities and the care taken by researchers.One attendee was Eric Dingwall, the research officer of the Society for Psychical Research. Some days before departing for Poland he prepared a sealed enveloped that contained a piece of paper with drawing and writing (see illustrations in side panel) . Dingwall writes:

The following words were written at the top of the paper before placing it within the first envelope: “Les vignobles du Rhin, de la Moselle et de la Bourgogne donnent un vin excellent.” On the lower half I drew an exceedingly rough design which was meant to convey the idea of a bottle without actually being a picture of one … This I enclosed within three lines, the fourth being supplied by the left hand edge of the paper.19Dingwall (1924), 259.

Dingwall added the date, then folded the paper and placed it in an opaque red paper envelope, which he then inserted into a tight-fitting black envelope. This in turn he inserted into a brown envelope, which he sealed. As a further precaution he pricked a pinhole through the package at each of the four corners, which would indicate if the package had been surreptitiously opened, as the holes in the envelopes would be out of alignment.

In Warsaw, Dingwall handed the package to a German psychical researcher, who took it to a sitting that had been arranged with Ossowiecki that evening, along with two sealed (white) envelopes that had been prepared by other researchers.Ossowiecki was handed the three envelopes, and selected the brown one (Dingwall’s). He then made various statements. Some of these were accurate observations about the individuals who had prepared the two other envelopes. The relevant information about Dingwall’s envelope was as follows:

The letter that I am holding has been prepared for me … I cannot understand … I see red . . . something red . . . colours … [Long pause.] I do not know why I see a little bottle …There is a drawing made by a man who is not an artist. . . something red with this bottle . . . There is without any doubt a second red envelope . . . There is a square drawn at the corner of the paper. The bottle is very badly drawn. I see it ! I see it ! … I see it ! I see it ! at the corner on the other side. In the middle something also is written, on the back …

Ossowiecki now drew a rough bottle. Asked what language the text was, he replied that it was in French. He continued:

The bottle is a little inclined to one side. It has no cork. It is made up of several fine lines. There is first a brown envelope outside; then a greenish envelope, and then a red envelope. Inside, a piece of white paper folded in two with the drawing inside. It is written on a single sheet.

The experiment was concluded at the conference session the following morning. Dingwall confirmed that the package had not been opened, then opened it and copied the writing and drawing onto the blackboard next to Ossowiecki’s drawing, which had been copied there earlier. It was a perfect match and created great excitement in the conference hall.20Dingwall (1924);Barrington et al., 62-64. Dingwall writes, ‘I had no doubt that the test was valid and that the knowledge of the contents had been ascertained by M. Ossowiecki through channels not generally recognised’.

A later experiment was carried out on the initiative of Theodore Besterman, a SPR researcher who made Ossowiecki’s acquaintance during a visit to Warsaw early in 1933. Some months later he arranged for a package to be delivered to Ossowiecki containing a drawing of an ink bottle on a piece of paper that was wrapped within three envelopes, in such a way that it could not be covertly opened and resealed.A British associate of Besterman handed the package to Ossowiecki who described the contents and made a drawing in front of him and other observers. These were returned to Besterman together with the package. Besterman characterized Ossowiecki’s performance as ‘brilliant’, confirming that the package had not been opened or tampered with and that Ossowiecki’s drawing of an ink bottle exactly matched his own.21Besterman (1933), 350.

Jonky Experiment

Efforts were often made to distinguish between clairvoyance and telepathy and to eliminate the latter. One such experiment came about by accident, involving Ossowiecki and other clairvoyants.

In 1925, Prosper Szmurło, a Polish psychical researcher, on a visit to Vilnius in Lithuania, was given a package by a man named Dionisy Jonky with a request that it should be handed to Ossowiecki to see if he could identify the contents, which Jonky stressed were known only to himself.However, the proposal was not followed up and the package lay forgotten in a drawer. Ten years later Szmurło learned that Jonky had died in 1927. These circumstances offered a unique possibility: if Ossowiecki was able successfully to identify the contents of the package without opening it, this could not be attributed to a telepathic connection with the living person who created it, but only to clairvoyant perception.

The experiment was carried out in January 1935, in which 17 clairvoyants, Polish and French, were asked to give readings. None was assuccessful as Ossowiecki, whose description included not only the objects placed inside the box (rocks and pieces of meteorite), but also images that corresponded to a report of an aircrash found on a newspaper used to wrap the rocks. Ossowiecki also mentioned pieces of sugar, traces of which were found in part of the outer cardboard box (it is not known whether Jonky intended to include the sugar, or whether its presence was accidental).22Barrington et al. (2005), 80-84; Revue Métapsychique (1936); Sołowianiuk, 2014.

Archeological Experiments

Ossowiecki habitually added information about the circumstances of the target’s creation, and this was mostly judged correct by the witnesses, sometimes in every detail. This applies also to the many impromptu experiments not recorded officially. Professor Stanisław Poniatowski, a Polish ethnologist and anthropologist, hoped to apply this clairvoyant perception in experiments as a means to explore prehistory.He conducted 33 experiments with Ossowiecki between 23 April 1936 and 20 May 1942.

Poniatowski perished during the war, but the manuscript of his unpublished report survived and excerpts from it were published in Poland and abroad.23Barrington et al. (2005) lists the archaeological experiments available in print at that time, 159-64. Its full text was finally published in book form in 2008.24Poniatowski (2008).In 2009, on the initiative of Mary Rose Barrington, the Society for Psychical Research commissioned a project aimed at reexamining the experiments. Accordingly, analysis and evaluation was carried out in 2010 by a Polish archaeologist, Professor Jacek Woźny, resulting in a complex report. (This, together with the relevant excerpts from a book by Poniatowski, can be read by members of the Society at the Lexscien online library).25Weaver (ed.) (2021).

Zofia Weaver

Literature

Barrington, M.R., Stevenson, I., & Weaver, Z. (2005). A World in a Grain of Sand. McFarland & Co.

Besterman, T. (1933). An experiment in ‘clairvoyance’ with M. Stefan Ossowiecki. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 41, 345-51.

Boruń, K., & Boruń-Jagodzińska, K. (1990). Zagadki Jasnowidzenia [Mysteries of Clairvoyance]. Epoka.

Bugaj, R. (1994). Fenomeny Paranormalne (Paranormal Phenomena). Adam.

Dingwall, E.J. (1924). An experiment with the Polish medium Stephan Ossowiecki. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 21, 259-63.

Geley, G. (1927). Clairvoyance and Materialization. T. Fisher Unwin Ltd/Kesinger Legacy Reprints.

Grzymała-Siedlecki, A. (1962). Niepospolici ludzie w swoim dniu powszednim (Extraordinary people in their everyday life). Chapter in Przybysz z czwartego wymiaru (Visitor from the fourth dimension), 278-94. Wydawnictwo Literackie.

Jacyna, J. (1926). 30 Lat w Stolicy Rosji (1888-1918) (30 years in the capital of Russia (1888-1918)). F. Hoesick.

Ossowiecki, S. (1933/1976). Świat Mego Ducha i Wizje Przyszłości (The World of My Soul and Visions of the Future). Warszawa, Dom Książki Polskiej. 1976 ed.: Chicago, Illinois, USA: Astral Editorial Office.

Polski Słownik Biograficzny [Polish Biographical Dictionary] (1979). PAN.

Poniatowski, S., & Bugaj, R. (eds.) (2008). Pierwsze próby parapsychicznego sondowania kultur prehistorycznych (First attempts at parapsychical probing of prehistoric cultures). Arcanus.

Sołowianiuk, P. (2014). Jasnowidz w Salonie (Clairvoyant in the Living Room). Iskry.

Woźny, J. (2009). Wizja prehistorii Stefana Ossowieckiego a współczesna archeologia. [Stefan Ossowiecki’s Vision of Prehistory and Contemporary Archaeology]. Unpublished report for the Society for Psychical Research, Lexscien online library.

Weaver, Z. (ed. & trans.). (2021). Archaeology Experiments with Stefan Ossowiecki Carried Out by Professor Stanisław Poniatowski, with Assessment and Comments by Professor Jacek Woźny. Lexscien online library.