This Indian case of a child who recalled a previous life is important for several reasons. It was investigated three times, independently, with the first investigator, a native speaker of the same language as the families involved, making a record in writing of the girl’s statements before identifying the person she remembered having been. The girl had a birthmark which turned out to correspond to wounds on the previous person, as documented in a medical report.

Contents

Shakuntala Maheshwari

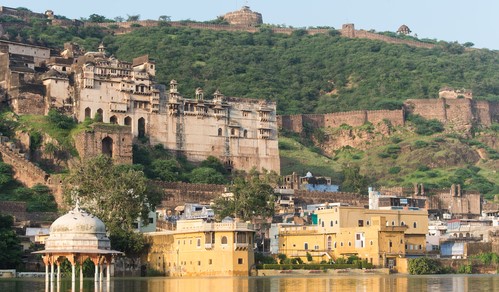

Shakuntala Maheshwari was born on 22 February 1960, in Kota, Rajasthan, India. She had two older brothers, but was her parents’ first and only daughter.

Late in the afternoon of 27 April 1968, Shakuntala was playing with a younger cousin on the narrow balcony of her house, fronting an interior courtyard. Her mother heard her cry out that her cousin might fall, but she herself fell, hitting her head on the concrete floor about five metres (15 feet) below. Her mother found her unconscious with blood streaming from her right ear.

Shakuntala’s mother rang her father, who returned home immediately and carried her to hospital. Upon admission, she was unconscious, vomiting, and bleeding from the right ear. No neurosurgeon being available, her treatment consisted of supportive measures only. Her condition deteriorated and she died nine hours later, without having regained awareness.1Stevenson (1997), 474-75.

Sunita Khandelwal

Sunita was the sixth of her parents’ eight children. At her birth on 20 September 1969, she was seen to have a sore roughly 2.5 centimetres (one inch) in diameter but of irregular edges on the right side of her head. It was haemorrhaging, so her parents applied talcum powder, and after three days, the bleeding stopped. In his report of the case,2Stevenson (1997), 468-91. Ian Stevenson described the resulting birthmark as a ‘hairless, slightly elevated, slightly puckered, and hyperpigmented nevus [mole]’. No other member of her family had such a mark.

When Sunita first began talking about a previous life at two years of age, she demanded to be taken to Kota, a city 475 kilometres (295 miles) from her home in Laxmangarh. Her mother was not her ‘real’ mother, she insisted. If her parents did not take her to Kota, she would fall from the roof of their house and die, as she had before.3The account of Banerjee’s investigation is taken from the summary by Rawat & Rivas (2021, 91-95), who evidently had access to unpublished records.

Sunita said that she had been seven years old when she died. When pressed for details, she said was pushed by a cousin with whom she was playing, ‘because I had asked for water. I have come here to drink water.’ She would point to the birthmark on her head and say, ‘Look here. I have fallen.’

Sunita recalled many things about the previous life. She had two brothers, but no sister; an uncle older than her father, but no uncle younger than her father. Her paternal grandfather was living, but her paternal grandmother had died. Her family belonged to the Bania (merchant) caste, like her present family, but they were more affluent. Her father had a shop where he kept silver coins in a safe. The family possessed a car and a scooter on which her father would take her for rides. Her mother owned many saris.

When she was three and her parents still resisted making the journey to Kota, Sunita began refusing to eat until they did. She became so malnourished that her father sought medical treatment on several occasions. The family physician found Sunita to be ‘extremely agitated and disturbed’ and advised her father to go to Kota to pacify her, but still he resisted. Finally he took her to a closer city, telling her it was Kota, but Sunita was not fooled. ‘This is not Kota,’ she said. ‘This is Jaipur. You are telling lies and will be punished.’

This situation continued until Sunita was about five years old and a lawyer friend of her parents wrote down some of the things she was saying about the previous life, then sent a summary of seventeen items to Indian investigator HN Banerjee at the University of Rajasthan in Jaipur.

Banerjee’s Investigation

On 17 December 1974, Banerjee went to Laxmangarth to meet Sunita and her family. He spoke to Sunita about her memories, and wrote out a list of them. Items included:

- She lived in Kota in her previous life.

- The river Chambal flowed by Kota.

- Her family were members of the Bania caste [businessmen].

- Her father owned a shop in the Chauth Mata Bazar district.

- Her father kept silver coins in a big iron safe in his shop.

- Her family’s house was in Brijrajpura.

- She had two brothers but no sister.

- She had a paternal uncle older than her father (tau) but no paternal uncle younger than her father (chacha).

- Her paternal grandfather was living, but her paternal grandmother had died.

- Her mother owned many saris

- Her family owned a car.

- Her father used to take her out on a motor scooter.

- She drank a lot of milk in her previous life.

- When she lived in Kota her mother made narangi ka sag by crushing tangerines into juice, then throwing pieces of tangerine into a pot of melted sugar and adding some spices.

- They also at bijou ki barfi, made from milk and sugar, to which her mother would peeled cantaloupe seeds.

- Every year, her parents took her to a fair near their home in Kota.

- Her father would apply mehandi (henna) to her hands.

- She had died at the age of seven after falling from a height.

- She had fallen because she had been pushed by a cousin.

- She had hit the right side of her head, where she had her birthmark.

Banerjee knew that narangi ka prasad was made only by the Vaishnav Hindu devotional sect, who used the preparation for offerings during religious ceremonies. Narangi ka prasad was virtually unknown in Laxmangarh. The same was true of bijou ki barfi, another food typical of the Vaishnav sect and not usually eaten in Laxmangarh. There were many Vaishnav in Kota, however, and Banerjee proposed to take Sunita there to try to verify her memories. In the end, her parents gave in and accompanied them there.

In Kota, Banerjee wanted to see if Sunita could find her way to what she said had been her father’s shop. Without hesitation, she led the way to the Chauth Mata Bazar district and stopped in front of a shop full of silver ornaments. The proprietor turned out to be a man named Prabhu Dayal Mahashwari. Banerjee related to him what Sunita had been saying about her life in Kota.

Prabhu Dayal stated that he had had a daughter, Shakuntala, who had died after a fall from the interior balcony of their house, and confirmed many other things Sunita had been saying. He asked Sunita if she could find the way to their home. After some confusion, she led the group to a gate and announced, ‘This is the door to my house’. Prabhu Dayal confirmed that this was so.

Inside the house, Sunita did not recognize Shakuntala’s mother or brothers, but she pointed to a picture of Shakuntala and said, ‘This is my photograph’. Banerjee walked with her through the house, to observe her responses. When they reached the balcony from which Shakuntala had fallen, she reacted fearfully, clutching Banerjee, and said: ‘I’m afraid I might fall down’.

Banerjee noted that Sunita’s birthmark had the appearance of a healed wound and was located exactly where Shakuntala had been injured by her fall.

Sunita employed more English loan words in her Hindi speech than other members of her family did, but this was consistent with her having been Shakuntala, whose family spoke in this way. Sunita also referred to vegetables as sabzi, as Shakuntala’s family did, rather than bhaji, the term used by her own family.

In all, Banerjee recorded 34 statements Sunita made about her life as Shakuntala, the great majority correct. The only entirely incorrect statement was that her family possessed a car. Shakuntala had been eight, not seven, when she died, but the accident had occurred only two months after her birthday, so this was a near miss. Shakuntala’s mother, not her father, had applied henna to her hand as part of a healing ritual, so this memory was partially correct. Her memory of being pushed by a cousin was unverified, but considered doubtful.

Shakuntala’s family were much impressed by Sunita and quickly accepted her as the reincarnation of their daughter and sister. They invited her to visit them, which Sunita did several times over the ensuing years.

Stevenson’s Investigation

Sunita’s case came to the attention of a journalist in Kota, who wrote about it for a local newspaper in January 1975. One of Stevenson’s field assistants saw this story and brought it to his attention. He asked Satwant Pasricha to look into it, and she made her first to Kota in November 1975 and interviewed Prabhu Dayal, although she was unable to meet Sunita and her family in Laxmangarh that year.

In 1976 and 1978 Pasricha interviewed Sunita her family as well as Prabhu Dayal and his family. She was with Stevenson when he got personally involved in the investigation in March 1979. Pasricha and Stevenson continued their investigation and interviews on Stevenson’s trips to India in 1981 and 1986.

Stevenson did not consult with Banerjee about his earlier investigation, so it is noteworthy that with some minor exceptions, what he and Pasricha learned agrees with Banerjee’s findings.4Stevenson (1997), 475-83.

Stevenson also was able add new details and documentation, for instance, regarding Sunita’s intermission memories. After she died, Sunita said, ‘I went up. There was a baba (holy man) with a long beard. He checked my record and said: “Send her back.” ’ On another occasion, she remarked, ‘When I fell from a small height, I got a mark, but when I was thrown down from a great height, I got no mark.’

Stevenson obtained medical records from the hospital to which Shakuntala was taken after her fall. The notes of admission recorded that she had fallen from the second storey of the house. She was unconscious, vomiting and bleeding from her right ear, consistent with having been hit the right side of her head, as Sunita claimed, and where her birthmark was located.

Stevenson tried to determine how many other children of Kota matched Sunita’s memories. He and Pasricha searched the records of the hospital to which Shakuntala was taken, but could find no children who had died as a result of a fall like Shakuntala’s.5Stevenson (1997), vol. 1, 468-91.

In his overall assessment of the case, Stevenson discounted Sunita’s finding Prabhu Dayal’s shop and home, her recognitions of her photograph and the place Shakuntala had died, saying that she could have been influenced by those around her in doing these things. However, taking into account the variety of correct statements she made, her corresponding behaviours, and her birthmark consistent with Shakuntala’s head wound, he concurred with Banerjee and Shakuntala’s family that Sunita did indeed appear to be recalling Shakuntala’s life and death.6Stevenson (1997), 489-90.

Later Developments and Rawat’s Investigation

By the time she was twelve years old, in 1981, Sunita was no longer speaking spontaneously about the previous life. Her parents believed that she still had some memories but she kept these to herself, and they did not ask about them. Sunita continued to visit Shakunthala’s family in Kota and was received cordially by them.

When he studied the case in 1986 and again in 1997, KS Rawat was told by Shakuntala’s family that they saw in Sunita traits of personality that resembled Shakuntala. Sunita’s brother informed Rawat that Shakuntala’s family had once offered ‘lakhs of rupees’ (a considerable sum) for Sunita, but that her parents had politely declined the offer.

Rawat learned that Shakuntala’s family continued to invite Sunita to celebrations.7Rawat & Rivas (2021), 94. Stevenson also heard of this persisting relationship between Sunita and Shakuntala’s family, long after her memories seemed to have faded. Sunita continued to observe the rakhi ceremony, in which Hindu brothers and sisters renew pledges of devotion and support to each other, with Shakuntala’s brother.8Stevenson (1997), 490. When Sunita married in July 1989, Shakuntala’s family contributed about 50% of the costs of the bride’s family and performed in the ceremonies a ritual ordinarily carried out by the bride’s parents.9Stevenson (1997), 491.

James G Matlock

Literature

Rawat, K.S., & Rivas, T. (2021). Reincarnation as a Scientific Concept: Scholarly Evidence for Past Lives. Hove, UK: White Crow Books.

Stevenson, I. (1997). Reincarnation and Biology: A Contribution to the Etiology of Birthmarks and Birth Defects. Vol. 1: Birthmarks. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Praeger.