Kirlian photography uses high-voltage electricity to reveal coronas and light streamers radiating from living organisms and other objects. The technique was pioneered by in Russia by Semyon and Valentinia Kirlian and introduced to the West in the early 1970s. The claim that such photography reveals a life-energy unknown to science is contested by critics, who consider the effect to be an ordinary electrical phenomenon.

Background

Early information about the photography process known as ‘Kirlian’ comes from Victor Adamenko, a Russian biophysicist. He traces it as far back as the 1890s, when a Russian engineer named Yakov Narkevich-Todko demonstrated ‘electrographic photos obtained with the help of quiet electrical discharges’. Electrical discharges of the type commonly referred to as St Elmo’s fire had been previously observed, and had been made to appear by Nikola Tesla while generating artificial lightning.1

Adamenko also noted that Czechoslovak researchers Prat and Schlemmer published a paper in 1939 in which they describe a photographic technique revealing a glow around leaves. This resembled images produced in a similar way in the same year by Semyon and Valentinia Kirlian of Kazahk State University. The Kirlians observed that a fabric impermeable to infrared, visible and ultraviolet light did not hinder the reproduction of the corona.2

The Kirlians

The Kirlians’ work was part of extensive research in the Soviet Union on psychoenergetics, which included acupuncture, energy transference between living and dead objects, psychokinesis and other topics.3 They continued to work on their method for some thirty years before it was introduced to the English-speaking world.

On a visit to the Soviet Union in 1971, Thelma Moss met the Kirlians, who in the spirit of international cooperation gave them plans and blueprints for building the equipment. The First Western Hemisphere Conference on Kirlian Photography, Acupuncture and the Human Aura was held in New York on May 25, 1972.

In a paper presented at this first conference, the Kirlians explain the method in detail. Its principle is ‘the transformation of non-electrical properties of the photographed subject into electrical ones via motion of a field in which the controlled transfer of a charge from an object to a photographic film or screen takes place’.4 In a high-frequency electrical field, they state, auto-electron and auto-ion emission is characteristic of all objects including living organisms.

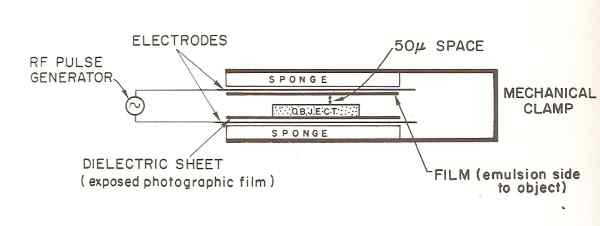

In the simplest version of the Kirlian device, the object to be photographed is placed between two electrodes, along with film whose emulsion side faces the object. The electrodes and the object are separated by space or dielectric (insulating) material. A pulse of high-frequency, high-voltage current is run through the electrodes, the image subsequently appearing on the developed film.

Figure 1: Simple Kirlian device.5

The Kirlians developed different types of apparatus, such as a soft, flexible plate for photographing the entire surfaces of diversely-shaped objects and a device to create motion pictures.

In their experiments, the Kirlians found that an inanimate object, photographed more than once with the same settings, would always appear the same. A living organism, however, would appear differently in successive photographs, its varying condition determining its dielectric structure. The physical, chemical and dynamic characteristics of the object are translated into electrical characteristics, which appear as ‘geometric, dynamic colored figures’.6

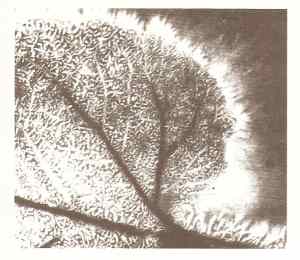

The Kirlians write: ‘By studying the geometric figures, their spectrum and dynamics of development, it will be possible to judge the biological state of an organism and its organs including disease and pathology’.7 For example, the electrical characteristics of a withered ageratum leaf are seen to differ from those of a healthy one (Figures 2).

Figure 2: healthy leaf, left; withered leaf, right.8

The Kirlians describe how a living organism such as a person can be photographed through the use of just one dielectric plate. When colour film is used, they write, different parts of a person’s skin produce different colours: the heart region, for example, is an intense blue, the forearm is greenish blue and the thigh is olive, suggesting possible diagnostic value in medicine for early detection of disease.

They also describe an apparatus that allows visual observation of the coronal phenomena in real time, and what can be seen, for example, on a person’s skin:

On some sections of skin, points of blue and gold abruptly flare up. Their characteristic features is a rhythm of flashes and immobility. Some clusters constantly splash out from one point of the skin to another where they are absorbed. It must be noted that until one cluster is absorbed, the next will not splash out … the colors of the clusters may be milky blue, pale lilac, gray, or orange’.9

William Tiller notes that these flares resemble the activity of plasma on the surface of the sun.10

One of the most striking images created by the Kirlians was a leaf from which a section had been cut. The photo showed coronal discharges from where the original outer edge of the removed section should have been, which was interpreted by some Soviet scientists to mean the photo was showing the leaf’s life energy or ‘bioplasma’.11

Kirlian photography, the Kirlians write, gives science and technology a new means of studying nature by observing the electrical states of objects.

Other Experiments

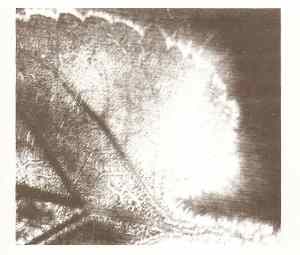

Thelma Moss and Kendal Johnson of the UCLA Center for the Health Sciences in Los Angeles experimented with techniques similar to the Kirlians’. They found that neither heating nor freezing a coin changed its aura, so long as the photographic parameters remained constant. By trying all frequencies, they learned that bright, sharp images are produced at different frequencies as one goes up the scale, perhaps due to ‘some law of harmonics’.12 They were unable to replicate the Kirlians’ ‘phantom leaf’ effect, but noticed changes to a leaf appearing after injury, such as blue bubbles filling its spine. With human subjects, Moss and Johnson ruled out galvanic skin response as an explanation by testing it with standard instrumentation while simultaneously taking Kirlian photographs and finding no correlation. They did the same with vasoconstriction and vasodilation, again finding no correlation. Other experiments ruled out skin temperature and sweat as explanations for the photographed streamers of light.

Moss and Johnson had better results correlating changes in mental state due to alcohol, marijuana, meditation, acupuncture treatment and hypnosis, showing that a relaxed state usually produced a more brilliant, wider blue-white corona, while states of emotional excitement or tension produced red blotches. One subject was found to be able to change his corona at will by generating anger or fear within himself; other subjects’ coronas changed depending on who was photographing them.

Figure 3: Effect of alcohol (bourbon) consumption on corona.13

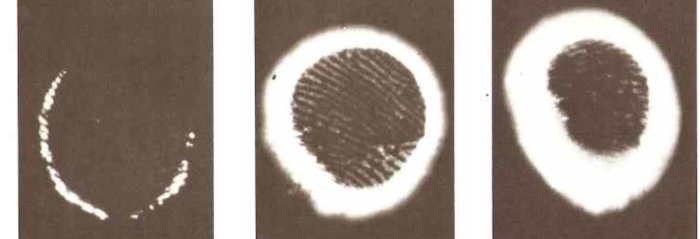

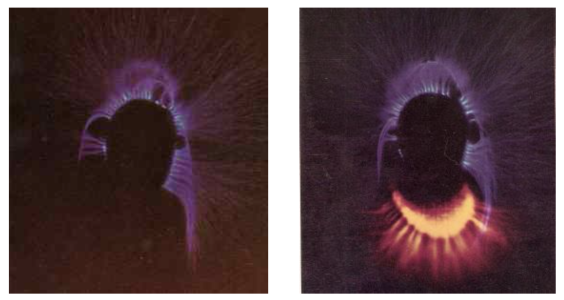

E Douglas Dean of the Newark College of Engineering experimented by photographing a psychic healer’s finger. The corona was brighter while she thought of healing than not, and brighter still while she was in the act of healing.

Figure 4: Healer’s finger at rest, left; while performing healing, right.14

In reviewing Soviet work on Kirlian photography, Tiller notes that when two people’s fingers are photographed close together, the coronas don’t overlap each other, but deform so as to form a slight space between them. He also notes that Soviet scientists found that major flares on the body correspond to the points on the Chinese acupuncture chart, suggesting they are visual depictions of some form of life-related energy.

While scientific research on Kirlian photography has essentially died out in the West, rejected by the mainstream, it has continued in Russia. The Russian scientist Konstantin Korotkov developed a technique similar to Kirlian photography called ‘gas discharge visualization’ (GDV), and has written several books and papers in English. He is unequivocal in maintaining that his method shows a form of life energy, and writings on his website reveal that bio-electricity continues to be studied, and indeed used in clinical settings, in Russia.

For instance, a blind study of 542 patients was conducted at Sochi University, comparing diagnostic effectiveness of Korotkov’s GDV method and regular diagnosis by examination. GDV was found to have a predictive power of matching the regular diagnosis of 94%. Another researcher found GDV was correct 90% of the time in predicting whether a pregnant woman would have a miscarriage. GDV diagnosis has been tested and used on tens of thousands of Russian patients.15

Criticisms

The light effects visible in Kirlian photography have frequently been attributed to ordinary factors. For instance Brian Millar, in a review of the collection of papers from the Second Western Hemisphere Conference published in the Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, attributes most of the light effects to film buckling allowing light to enter the apparatus, water vapour being emitted from the skin and galvanic skin resistance (despite Moss and Johnson’s experiment showing no correlation).16

Currently, the critical consensus seems to be that the corona and streamer effects are caused by gas ionization around the object being photographed due to moisture contained in it, which is naturally higher in living organisms, and decreases as they die. Pehek, Kyler and Faust concluded this after their experimentation with the Kirlian method, writing: ‘during exposure, moisture is transferred from the subject to the emulsion surface of the photographic film and causes an alternation of the electric charge pattern on the film’. Cooper and Alt tested Kirlian photography in a vacuum and found no images were produced.17 Sceptic writer Terence Hines argues that a life-energy field should not disappear in a vacuum, and notes also that emotional arousal produces greater moisture on the skin, potentially explaining the changes in image.

The Kirlian effect seen with finger photos was attributed by James Randi to finger-pressure, illustrated by a Kirlian image that had been altered by changed pressure of his own fingers.18

In the Skeptic’s Dictionary, Robert Todd Carroll attributes the phantom leaf outcome to ‘to fraud or to residues left from the initial impression of the whole leaf’.19

Art and Imaging

While Kirlian photography is not accepted as a diagnostic or scientific tool by mainstream Western science or medicine, it is used by photographers and artists for creating images. Instructions abound on how to construct devices for producing Kirlian images, and commercial devices are available to purchase.

Links

Kirlian images may be seen here and here

Shooting real-time Kirlian video

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Hines, T. (2003) Pseudoscience and the Paranormal. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Kirlian, S.D., & Kirlian, V.K. (1973). Photography by means of high-frequency currents. In Galaxies of Life: The Human Aura in Acupuncture and Kirlian Photography, ed. by S. Krippner & D. Rubin, 13-27. New York: Gordon & Breach/Interface.

Krippner, S., & Rubin, D. (eds.). (1973). Galaxies of Life: The Human Aura in Acupuncture and Kirlian Photography. New York: Gordon & Breach/Interface.

Millar, B. (1976). Review of The Energies of Consciousness, ed. by S. Krippner & D. Rubin (Gordon and Breach, New York and London, 1975.) Second Western Hemisphere Conference on Kirlian Photography, Acupuncture and the Human Aura. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 48, 343-45.

Moss, T., & Johnson, K. (1973). Bioplasma or corona discharge? In Galaxies of Life: The Human Aura in Acupuncture and Kirlian Photography, ed by S. Krippner & D. Rubin, 29-51. New York: Gordon & Breach/Interface.

Rabe, L (2007). IHN - Infinite human nature AB EPC/EPC/GDV general representative. [Web page, in Russian.]

Randi, J. (1982). Flim-Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns and Other Delusions. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books.

Tiller, W. (1973). Some energy field observations of man and nature. In Galaxies of Life: The Human Aura in Acupuncture and Kirlian Photography, ed by S. Krippner & D. Rubin, 71-111. New York: Gordon & Breach/Interface.

Toth, M. (1973). Historical notes relating to Kirlian photography. In Galaxies of Life: The Human Aura in Acupuncture and Kirlian Photography, ed. by S. Krippner & D. Rubin, 1-12. New York: Gordon & Breach/Interface.

Endnotes

- 1. Cited in Toth (1973), 1.

- 2. Moss & Johnson (1973), 30-31.

- 3. See Tiller (1973) Fig. 36.

- 4. Kirlian & Kirlian (1973), 13.

- 5. Krippner & Rubin (1973), Fig. 38.

- 6. Kirlian & Kirlian (1973), 16.

- 7. Kirlian & Kirlian (1973), 17.

- 8. Krippner & Rubin (1973), Figs. 8 & 9

- 9. Kirlian & Kirlian (1973), 22.

- 10. Tiller (1973), 80.

- 11. Moss & Johnson (1973), 38-9.

- 12. Moss & Johnson (1973), 38.

- 13. Krippner & Rubin (1973), Figs. 23, 24 & 25.

- 14. Krippner & Rubin (1973), Figs. 34 & 35.

- 15. Rabe (2007).

- 16. Millar (1976), 343.

- 17. All sources in this paragraph cited by Hines (2003) 428.

- 18. Randi (1982), 8.

- 19. Carroll (2015). Kirlian photography (electrophotography), published online at Skeptic’s Dictionary.