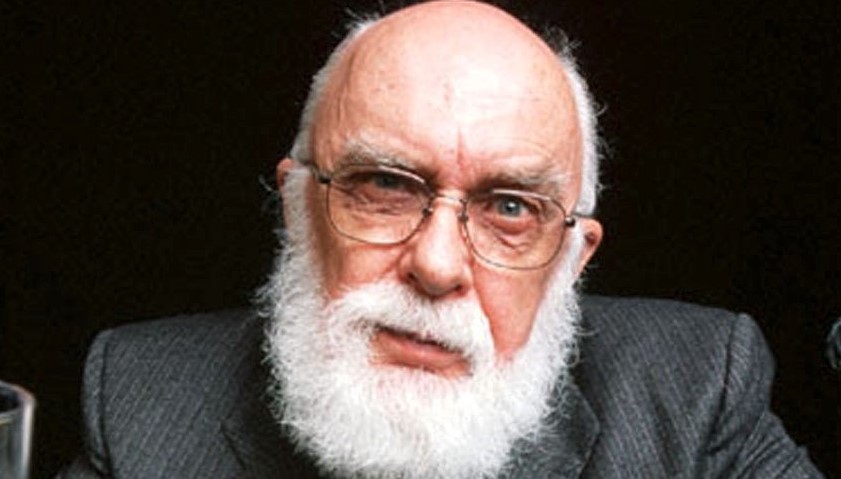

James ‘The Amazing’ Randi (1928–2020), was a professional conjurer and escapologist, who in later life became a public scourge of psychics, parapsychologists, faith healers and practitioners of alternative medicine. He was best known for his ‘One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge,’ an offer to pay $1 million USD to anyone claiming miraculous abilities who could pass his test.

Parapsychologists disputed Randi’s self-description as a paranormal investigator, viewing him rather as a crusading sceptic who employed polemics and dishonest practice to discredit scientific psi research. Some admirers were aware of his flaws, while defending his goals and motives.

Contents

Life

James Randi was born Randall James Hamilton Zwinge on 7 August 1928, in Toronto, Canada, to George Randall and Marie Alice Zwinge, née Paradis. He showed an early aptitude for magic, studying conjuring as a teenager after being inspired by seeing magician Harry Blackstone Sr perform. He dropped out of high school at age seventeen to join a carnival, working as a magician and mind-reader.1Biography.com Editors (2019). All information in this section is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted.

Taking the stage name James Randi, and later The Amazing Randi, Randi was inspired by the legendary escape artist Harry Houdini, of whom he later wrote a biography. Randi became famous for Houdini-type stunts such as freeing himself from an underwater coffin, or a straitjacket suspended over Niagara Falls. He went on to perform live worldwide and appeared frequently on television and radio shows, from children’s programs to Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show. He once toured with the horror-inspired rock musician Alice Cooper, playing an executioner who appeared to behead Cooper with a guillotine.2Paoletti, R. (2017). For video on his collaboration with Cooper, complete with beheading, see here.

Randi met his life partner Deyvi Orangel Peña Arteag (also known as José Alvarez) in 1986 when Peña was a 24-year-old art student. Peña became Randi’s assistant. In 2011 Peña was arrested, having been revealed to be a stealth refugee from homophobia in Venezuela rather than an American as he pretended, and falsely using the name ‘José Alvarez’. Charged with aggravated identity theft, Peña faced a six-figure fine, ten years in jail and deportation to his homeland. However, a letter campaign launched by his and Randi’s many friends in the art and sceptical worlds, along with charities to which they had donated, persuaded the court to lessen the charge and allow Peña to stay in the US. It is unclear whether Randi was aware of Peña’s ruse. He and Randi were married in 2013.3Higginbotham (2014).

Randi retired in 2015 and until his death in 2020 continued to live with Peña in Florida, giving occasional appearances and lectures.

Sceptical Activism

Randi rejected religion from early childhood, saying ‘I have always been an atheist; I think that religion is a very damaging philosophy – because it’s such a retreat from reality’,4Higginbotham (2014). and, ‘a belief in a god is one of the most damaging things that infests humanity at this particular moment in history’.5Center for Inquiry (2017). He began sceptical activism aged fifteen, attempting to publicly expose fraudulent séance activity being carried out in a church. For the disruption he was arrested and briefly jailed. The incident caused him to yearn for more of a position of authority from which to carry out debunking activity.6Taft (1981).

Randi gained fame as a debunker after appearing on The Tonight Show in 1973 together with Uri Geller, where he was later credited with having contributed to Geller’s failure to perform his psychic feats. He continued to publicly denounce Geller as a faker. In 1976, he co-founded the Committee for Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP), together with Paul Kurtz, Ray Hyman, Martin Gardner, Carl Sagan and others, becoming the organization’s executive director and public face.

In the 1980s, Geller launched libel actions against Randi and CSICOP. These were eventually dismissed, but the burden of legal fees on CSICOP led to Randi’s acrimonious departure.7Higginbotham (2014). Randi started his own debunking membership organization, the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF), in 1996, and later returned to the CSICOP as a Fellow.8The list of Fellows may be seen here. In 2015, JREF transformed itself into a granting body, providing about US$100,000 per year of funding to non-profit groups whose activities were aligned with its mission. It also ceased accepting memberships and donations.9Denman & Adams (2015).

Randi became a leading figure in the sceptic movement, through books, television programmes and other media appearances disputing the claims of psychics, parapsychologists and alternative medicine practitioners and carrying out media stunts to expose charlatans. He was known in particular for his Million Dollar Challenge, a monetary prize offered to anyone who could convince him they possessed psychic powers (see below).

Randi stressed that he created illusions through tricks that can be explained logically rather than by psychic or paranormal powers. He had no educational or work background in science, stating, ‘I am a professional conjurer and I have followed the minor music of Magic for more than four decades. As a conjurer, I possess a narrow but rather strong expertise: I know what fakery looks like’.10Randi (2011), first paragraph of the Introduction.

Randi said in an interview he disliked being called a debunker – ‘because that implies someone who says, “This isn’t so, and I’m going to prove it” ’ – and that he preferred the term ‘psychic investigator’.11Orlando Sentinel (1991), quoted in Fox (2020).

Peter Popoff

In 1986 Peter Popoff, a televangelist and self-described faith healer, was definitively exposed by Randi and others by means of a radio scanner at a public event. This revealed that the information about audience members which he appeared miraculously to know was being fed to him by his wife through an earpiece. Recordings of the deception were played by Johnny Carson on his The Tonight Show, leading to Popoff’s (temporary) disgrace and bankruptcy.12Randi (1987), Oppenheimer (2017).

Public Hoaxes

Successful stunts created by Randi to fool investigators and the media are often cited by admirers.

Project Alpha

In 1980, Randi persuaded two teenagers interested in stage magic, Michael Edwards and Steven Shaw, to pose as metal-bending subjects for an experimental program on psychokinesis being conducted at the McDonnell Laboratory for Psychical Research at Washington University.13Thalbourne (1995). See also Phillips (2022). Randi’s account of Project Alpha can be found in Randi (1983a) and Randi (1983b). The eventual aim was for the pair to be tested by parapsychological labs throughout the world, as a means to discredit parapsychology as a scientific endeavor. The pair succeeded in fooling investigators during early experiments, but their ability waned as the protocols were tightened. No academic papers claiming positive results were ever published.

Carlos

In 1987, Randi persuaded his partner Peña to play the main role in a hoax in collaboration with Australia’s 60 Minutes TV show, posing as a psychic channeler for a 2,000-year-old entity named ‘Carlos’. Randi primed Australia’s media with press releases describing the (non-existent) channeling activities of ‘Carlos’ in the US, gaining bookings for him to perform on television across the country. During his appearances, Peña acted the role with Randi feeding him lines through an earpiece. Following a climactic appearance at the Sydney Opera House, fans proved willing to buy ‘Carlos’s Tears’ for $500 each and an ‘Atlantis Crystal’ for $14,000 (no payment was accepted). The hoax was revealed a few days later on 60 Minutes.14Higginbotham (2014).

Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge

In 1964, Randi began offering a $1,000 cash prize to any psychic who could pass tests devised by himself. The sum on offer was increased to $10,000 for some years and eventually grew to $1 million, managed by JREF. It would be handed to any claimant who could successfully demonstrate any psychic, supernatural or paranormal ability under testing conditions agreed to by both the tester and JREF. The prize was never claimed and the offer was terminated in 2015. (A similar monetary award, for $250,000, is currently being offered by the Center for Inquiry Investigations Group.)

JREF promoted the Challenge as ‘a tool that people everywhere can use to evaluate paranormal and pseudoscientific claims, by asking, “if this claim were true, why hasn’t someone proven it and won the million?” ’15Taylor (2017). It continues to be cited by scientists as a main reason for disbelieving the claims of psychics and parapsychologists.16E.g., Wagenmakers, Wetzels, Borsboom, & Maas (2011), 428.

Critics noted that its p-value requirements were far stricter than those generally used in science, and that since it ignored the standard scientific requirement for replication, its results are meaningless, a point made even by sceptic psychologist Ray Hyman. He wrote: ‘Scientists don’t settle issues with a single test, so even if someone does win a big cash prize in a demonstration, this isn’t going to convince anyone. Proof in science happens through replication, not through single experiments.’17Cited in Skeptical about Skeptics (2014).

Randi has been quoted as saying, with respect to the possibility that someone might succeed at the challenge, ‘I always have an out.’ He later asserted that the full quote was, ‘Concerning the challenge, I always have an out: I’m right!’18Taylor (2017).

Testing Dowsers

In an investigation filmed in March 1979 by an Italian TV company, Randi tested the ability of four dowsers to detect water flowing in underground pipes set up in a field near Rome. A successful demonstration would win $10,000, the size of Randi’s cash award at the time. Dowsers indicated the position of underground pipes by placing pegs in the ground: a demonstration would be considered successful if two-thirds of the pegs were within eight inches of a pipe. In an account published Skeptical Inquirer, Randi describes the failed attempts of all four.19Randi (1979).

Patricia Putt

In 2009, a preliminary test was carried out into claims by a British professional spirit medium Patricia Putt. Ten subjects were each given a reading, with the aim that five or more would later identify which of the ten was accurate for them. None of the matches was accurate.20French (2020).

Derek Ogilvie

In May 2008, JREF tested British psychic Derek Ogilvie, who claimed to be able to read the minds of babies, as an episode of Channel 5’s ‘Extraordinary People’ series.21IMDb (2008). Infants picked a numbered ball out of a bag, which indicated a certain object that they were then given to hold. Ogilvie, isolated in a sound-proof room, tried to identify the object, but scored at chance levels.

Controversial Claims

Many claims by Randi to have exposed paranormal claimants, accepted as definitive by many sceptics, are considered by critics to be weakly evidenced, speculative or invented (Randi agreed in an interview that he sometimes lied for effect, whether consciously or unconsciously he was not always sure).22Storr (2014).

Uri Geller

Randi’s exposure of Hungarian-Israeli psychic Uri Geller rested on his claim that he could duplicate his tricks by sleight-of-hand and his description of how this is done. Many other stage magicians who observed Geller expressed doubts that what they witnessed could be achieved by trickery, notably the effect of a key or spoon continuing to bend when he had stopped touching it, and sometimes when he was no longer present.23Urigeller.com (n.d.)

Randi’s 1973 appearance with Geller on The Tonight Show boosted his profile as a paranormal debunker and started a long-running public feud between the two. Randi advised the producers beforehand to ensure that any props such as metal cutlery be provided by them rather than by Geller, to guard against trickery.24Higginbotham (2014). On the show, Geller was asked to identify which of a set of nine canisters contained water, but failed and complained of being pressured. He was somewhat more successful when attempting to exert psychic force on a spoon held by a fellow guest, which showed a slight bend, but the dominant impression was negative, and the incident is widely cited as evidence against Geller’s claims. However, some viewers were impressed, and his appearance led to him being booked for the Merv Griffin Show, effectively launching his career in the US.25Higginbotham (2014).

In 1975, Randi published The Magic of Uri Geller (later retitled The Truth About Uri Geller) claiming to expose Geller as a faker, and continued to attack him publicly. Although Geller’s legal suits failed, he has credited Randi’s pursuit of him with helping him to achieve stardom, calling him ‘my most influential and important publicist’.26Higginbotham (2014).

Ted Serios

In 1967, Denver psychiatrist Jule Eisenbud published an account of his detailed investigations of demonstrations of ‘thoughtography’ by Ted Serios.27Eisenbud (1967). Randi claimed on the Today morning television program that he could reproduce these feats by sleight-of-hand, and under the same conditions that Serios had been subjected to in controlled conditions. It is not clear whether Randi understood that this would have meant being strip searched, including a thorough examination of body orifices, then clad in a monkey suit and sealed in a steel-walled, lead-lined sound-proof chamber. Pressed to make good on his claim, Randi subsequently declined to be tested, as correspondence – suppressed by Randi at the time – now clearly shows (see here).28Braude (2016), section ‘Eisenbud’s Challenge to Randi’.

Tina Resch

In March 1984, media attention on poltergeist activity associated with Tina Resch, an American teenager, attracted the attention of CSICOP. Randi and two colleagues went to investigate, accompanied by reporters and TV crews.29Roll & Storey (2004). However, on the advice of parapsychologist William Roll, who was himself investigating the incident, the Resch family refused to meet with Randi or admit him into their home (they were prepared to admit his two colleagues but they declined). Randi’s subsequent claim that Tina faked the phenomena, largely based on his analysis of photographs,30Randi (1985), 223-8. was disputed by Roll and others.31See McLuhan (2010).

Jacques Benveniste

In 1988, Randi took part in an intervention to discredit claims by Jacques Benveniste, a French immunologist, to have demonstrated that water can retain a biologically active memory of a substance that it no longer contains (a principle underlying homeopathy). Randi accompanied science magazine editor John Maddox and scientific fraud investigator Walter W Stewart to Benveniste’s laboratory, where they claimed to have conducted failed replications and uncovered experimental flaws.32Maddox, Randi & Stewart (1988). Benveniste and his supporters disputed their findings.33Josephson (1997).

Rupert Sheldrake

In 1998, biologist Rupert Sheldrake published a study suggesting the existence of a telepathic bond between a dog and its owner. Sheldrake later came across an article in which Randi was quoted saying in relation to canine ESP, ‘We at the JREF [James Randi Educational Foundation] have tested these claims. They fail.’ In an email replying to Sheldrake’s request for clarification, Randi indicated that these tests were not done at the JREF, but were ‘informal’ tests of dogs belonging to a friend and done some years ago. According to Sheldrake, Randi added: ‘I overstated my case for doubting the reality of dog ESP based on the small amount of data I obtained. It was rash and improper of me to do so.’

Gary Schwartz

In 2001, scientist Gary Schwartz’s mediumship research attracted a critical response from Randi titled, ‘May the Schwartz Be with You, the Tooth Fairy’s Existence Proven by Science!’, dismissing it as ‘games and amateur probes’.34See Schwartz (2001). In a response published online, Schwartz asserted that Randi’s criticisms ‘lack understanding and integrity’ and answered them point by point.35Schwartz (2001). More substantive criticisms were made by sceptic psychologists.36See McLuhan (2010), 148-50.

Parapsychology

Randi expressed contempt for parapsychologists, whom he called by such names as ‘psi-nuts’ and ‘wide-eyed nincompoops’.37Randi, Flim-Flam!, 217, 222. But he seldom criticized laboratory-based psi testing in any detail and appeared to lack substantive knowledge of what it involves. In 1982 he published an eight-page pamphlet, Test Your ESP Potential: A Complete Kit with Instructions, Scorecards and Apparatus, describing how ESP-tests are administered and how to avoid pitfalls. According to a reviewer, parapsychologist Ramakrishna Rao, Randi seemed not to not know how to design and conduct an ESP test, and lacked understanding either of double-blinding or the problems involved in recording errors. Furthermore, the statistical table he provided appeared to have been produced by an amateur, while the test cards were of such poor quality, the symbols were visible from the back.38Rao (1984).

About Randi’s 1995 book An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural (published in the UK as The Supernatural A-Z), fellow sceptic Susan Blackmore wrote that it ‘might have served as a useful entry into the whole subject but I am sorry to say that it has too many errors to be recommended in this way’.39Blackmore (1996), 270.

A representation of parapsychologists’ views on Randi’s work can be found here.

Recent Commentary

Randi’s death in October 2020 was extensively reported.

Mainstream Obituaries

Obituaries in mainstream outlets were generally laudatory. The Guardian described his paranormal ‘debunking’ in positive terms referring to the Million Dollar Challenge and lamenting the death of an ‘effective sceptic’ in the age of anti-vaxx, anti-5G and anti-Covid-19 conspiracy theories. CNN, New York Times and Daily Mail made similar assessments, citing his role in the founding of CSICOP and his ‘debunking’ of Uri Geller on The Tonight Show in 1973. Rolling Stone Magazinequoted science populariser Bill Nye: ‘He left the world better than he found it. He will be missed.’

Criticism and Support

A critical article in Boing Boing by Mitch Horowitz characterized Randi as ‘the man who destroyed skepticism’. Expressing views commonly held by the targets of his attacks, Horowitz compared him to Joseph McCarthy as ‘a showman, a bully, and, ultimately, the very thing he claimed to fight against: a fraud.’ He charged that Randi smeared serious researchers like JB Rhine and Dean Radin and made claims that he could not back up, for instance citing the claim of failed replications of pet telepathy.

Horowitz also queried what the JREF does with its considerable monetary resources, and the level of executive compensation at JREF, which at an average $197,000 is nearly three times the compensation of nonprofit CEOs in its revenue class.40Horowitz (2020).

Responding to Horowitz in his blog, David Gorski conceded that Randi was a ‘complicated’ and ‘polarizing’ figure, whose ‘flaws’ included an early scepticism of climate science, which he later reversed; a ‘tendency to say stupid things on occasion’, for instance comments that appeared to support eugenics, for which he later apologized; and a failure to the combat the ‘tolerance for misogyny and sexual harassment at TAM’. However, he went on to defend Randi, calling Horowitz’s article a ‘hit piece’ that uses ‘the sorts of rhetorical devices that skeptics have seen many times before from believers in woo’.41Gorski (2020).

In an article in Slate Magazine, Skepchick founder Rebecca Watson detailed her personal journey with Randi and the sceptic community from the late 1990s. She writes:

I got to know him as a sweet, kind, and complicated person. He treated everyone he met as the most important audience he’d ever have. He would randomly perform sleight of hand to the delight of everyone around him and needed no encouragement to launch into fascinating stories from his long and weird life. I saw him perform the same magic tricks dozens of times, and even well into his 80s I never saw his wrinkled hands slip up. I heard him tell the same stories dozens of times, and, as a true performer does, he only made the details more interesting and engaging each time.

As Watson relates, from 2010 she began to complain of sexism in the sceptical movement, campaigning for the male majority to be ‘more accepting of (or at least to stop randomly groping and awkwardly propositioning) women’. She complained that she got no help from Randi, who she said criticized her to others about trying to change the culture of the movement he founded.

She concludes:

I mourn for Randi, but I also mourn for what could have become of the movement he fathered. His undeniable charisma and showmanship motivated thousands to care about skepticism, but his stubbornness and inability to adapt may have doomed the skeptic movement to extinction.42Watson (2020a).

In a separate piece responding to Horowitz, Watson poured scorn on his defense of parapsychologists, but conceded that some of his criticisms were justified, for instance that Randi exaggerated feats such as Project Alpha.

Decades later, the story Randi would tell was that these researchers were completely fooled, refused several of Randi’s offers to help them detect fakes, and published several papers about the “psychic” boys. In fact, the researchers were sort of fooled, eventually did ask for Randi’s help, and never published any peer-reviewed papers (though they did give one credulous talk at a conference).43Watson (2020b).

Watson adds that Randi similarly exaggerated the effect of his ‘Carlos’ hoax, pointing out that ‘the Australian media was pretty sceptical of Carlos, and the theater that Randi claimed had been “packed” to see him was about half empty according to the Australian Skeptics organization’.

Books on Parapsychological and Paranormal Topics

Randi, J. (1982). Flim-Flam!: Psychics, ESP, Unicorns, and Other Delusions. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Randi, J. (1982). Test Your ESP Potential: A Complete Kit With Instructions, Scorecards, and Apparatus. New York: Dover Publications.

Randi, J. (1982). The Truth About Uri Geller. New York: Prometheus Books. [Originally published 1975 as The Magic of Uri Geller. New York: Ballantine Books].

Randi, J. (1990). The Mask of Nostradamus: The Prophecies of the World’s Most Famous Seer. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. [Republished 1993. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books]

Randi, J. (1991). James Randi: Psychic Investigator. London: Boxtree Ltd. [Companion book to the Open Media/Granada Television series.]

Randi, J. (1995). An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Published in the UK as The Supernatural A-Z: The Truth and the Lies. London: Headline, 1995.]

Lectures, Television, Film and Video

Randi has appeared in many TV shows and films, playing characters in a few but mostly appearing as himself. They are listed on his Wikipedia entry here. Many of his appearances can be found on YouTube. A documentary on his life, An Honest Liar, was released in 2014. Website here, IMDb listing here.

Lists of publications for which Randi has written and places where he has spoken, up to 2009, can be found here.

Awards

Randi has received many awards, mostly from sceptical, humanist and atheistic organizations, for his sceptical work, as well as many more from various magicians’ organizations for his contributions to the field of conjuring. They include a MacArthur Fellowship and an honorary doctorate from the University of Indianapolis. The full listing may be viewed here.44James Randi Educational Foundation (n.d.).

KM Wehrstein & Robert McLuhan

Literature

Biography.com Editors (2019). James Randi biography. [Web page at The Biography.com, A&E Television Networks.]

Review of The Supernatural A-Z: The Truth and the Lies by S. J. Blackmore (1996). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 61, 270-72.

Braude, S.E. (2016). Ted Serios. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web post.]

Center for Inquiry (2017). A conversation with James Randi. [YouTube video.]

Dart, J. (1986). Skeptics’ revelations: Faith healer receives ‘heavenly’ messages via electronic receiver, debunkers charge. Los Angeles Times (11 May).

Denman, C., & Adams, Rick, (2015). JREF status9/1/2015. [Web page.]

Eisenbud, J. (1966/89). The World of Ted Serios: ‘Thoughtographic’ Studies of an Extraordinary Mind. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA, and London: McFarland.

Fox, M. (2020). James Randi, magician who debunked paranormal claims, dies at 92. New York Times (21 October).

French, C. (2009). Scientists put psychic’s claims to the test. The Guardian (12 May).

Gorski, D [as Orac] (2020). Did James Randi ‘destroy skepticism’? [Web page.]

Hansen, G.P. (1992). CSICOP and the skeptics: An overview. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 86/1, 19-63.

Higginbotham, A. (2014). The unbelievable skepticism of the Amazing Randi. New York Time Magazine (7 November).

Horowitz, M. (2020) The man who destroyed skepticism. Boing Boing (26 October).

IMDb (2008). The Million Dollar Mind Reader. [Documentary by Channel 5 for the series Extraordinary People.]

The James Randi Educational Foundation (n.d.-a). About James Randi. [Web page.]

The James Randi Educational Foundation (n.d.-b). The Million Dollar Challenge. [Web page.]

Josephson, B. (1997). Letter to New Scientist (1 November).

Maddox, J., Randi, J., & Stewart. W.J. (1988). ‘High-dilution’ experiments a delusion. Nature 334/6180, 287-90.

McClenon, J., Roig, M., Smith, M.D., & Ferrier, G. (2003). The coverage of parapsychology in introductory psychology textbooks: 1990–2002. Journal of Parapsychology 67, 167-80.

McLuhan, R. (2010). Randi’s Prize: What Sceptics Say About the Paranormal, Why They Are Wrong and Why It Matters. Leicester, UK: Matador.

Oppenheimer, M. (2017). Peter Popoff, the born-again scoundrel. GQ (29 November).

Paoletta, R. (2017). How James Randi perfected magic and became master of skeptics. [Web page.]

Phillips, P. (2022). The Project Alpha Papers. [Compilation of papers published online.]

Randi, R. (1979). A controlled test of dowsing abilities. Skeptical Inquirer 4/1 (Fall).

Randi, J. (1983a). The Project Alpha experiment, Part one: The first two years. Skeptical Inquirer 7/4. [Internet Archive version.]

Randi, J. (1983b). The Project Alpha Experiment, Part two: Beyond the laboratory. Skeptical Inquirer 8/1. [Internet Archive version; scroll down.]

Randi, J. (1985). The Columbus poltergeist case: Part I: Flying phones, photos, and fakery. Skeptical Inquirer 9/3.

Randi, J. (1986). The Columbus poltergeist case, in Science Confronts the Paranormal, ed. by K. Frazier. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Randi, J. (1987). The Faith Healers. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books. [Republished in 2011 under the same title, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA: James Randi Educational Foundation.]

Randi, J. (2001). May the Schwartz be with you, the Tooth Fairy’s existence proven by science! [Blog post.]

Rao, K.R. (1984). Review of Test Your ESP Potential: A Complete Kit With Instructions, Scorecards, and Apparatus by J. Randi (1982), New York: Dover Publications. Journal of Parapsychology 48, 356-58.

Roll, W., & Storey, V. (2004). Unleashed – Of Poltergeists & Murder: The Curious Story of Tina Resch. New York: Paraview Pocket Books.

Schwartz, G. (2001). Editorial. [Web page published on Survival Science.]

Skeptical about Skeptics (2014). James Randi. [Web page.]

Storr, W. (2014). James Randi: Debunking the king of debunkers. The Telegraph (9 December).

Taft, P.B. (1981). A charlatan in pursuit of truth. New York Times (5 July).

Taylor, G. (2017). The One Million Dollar Paranormal Challenge. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]

Thalbourne, M.A. (1995). Science versus showmanship: A history of the Randi hoax. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 89, 344-66.

Urigeller.com (n.d.) Quotes From Magicians. [Web page.]

Wagenmakers, E.J., Wetzels, R., Borsboom, D., & Maas, H. (2011). Why psychologists must change the way they analyze their data: The case of psi. Comment on Bem (2011). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100/3 (March), 426-32.

Watson, R. (2020a). How James ‘the Amazing’ Randi hindered his own movement. Slate (10 November).

Watson, R (2020b). No, James Randi didn’t ‘destroy skepticism’ by being skeptical. [Blog post.]

Weiner, D.H., & Nelson, R.D. (1987) (eds.). Abstracts and Papers from the Twenty-Ninth Annual Convention of the Parapsychological Association, 1986. Metuchen, New Jersey, USA & London: Scarecrow Press.