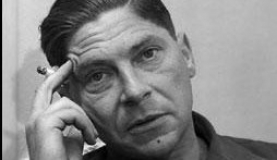

Arthur Koestler (1905–1983) was a Hungarian journalist and author, whose many writings included commentary on paranormal topics. His estate funds the Koestler Parapsychology Unit, an academic chair at Edinburgh University.

Contents

Life and Career

Arthur Koestler was born in Budapest on 5 September 1905 to Jewish parents. He was educated in Vienna, where he studied engineering, but was obliged by lack of funds to leave before graduating. In 1926 he travelled to Jerusalem and worked as a journalist for the German newspaper group Ullstein-Verlag. He was later posted in Paris and then Berlin.

Koestler joined the German Communist Party in 1931 believing that it was the only way to resist the rise of Nazism, but became disillusioned and resigned in 1938. He was imprisoned in Spain while working as a correspondent during the civil war; sentenced to death, he was released through the intervention of the British government.

He was interned in Paris as an ‘undesirable alien’ at the outbreak of World War II, and then again in the UK until 1941. His novel Darkness at Noon was published in English in that year.In 1942 he secured a job in the Ministry of Information and later travelled toPalestine as a correspondent for The Times.

Made financially secure by his writings, Koestler was able after the war to purchase properties in France and the US, before settling in Montpelier Square, London. He continued to travel and write extensively about political issues. In November 1960 he was elected to a Fellowship of The Royal Society of Literature.

In April 1968 he was awarded the Sonning Prize for his outstanding contribution to European culture. He received an honorary doctorate from Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada. In 1972 he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

In 1976 he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and in 1980 with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Around this time he founded the KIB Society together with Brian Inglis and Tony Bloomfield (the name is based on their initials), to promote research outside of conventional science; this later became the Koestler Foundation.

Koestler, a vice-president of the Voluntary Euthanasia Society, wrote a pamphlet on suicide.1Ceserani (1998). He and his wife Cynthia killed themselves on 1 March 1983 with an overdose of the barbiturate Tuinal taken with alcohol.

Psychical Research

Koestler became interested in the paranormal after experiencing psychical phenomena at an early age.

A solitary, rather frustrated child, he was reading alone in a room of a Viennese pension, when a tin of baked beans suddenly exploded and hit him on the head, after which some of his fellow boarders sought him out for ‘table-turning sessions’. As a grown man he was fascinated by a recurrent sense of an ‘invisible writing’, an elusive hidden meaning in what looked like coincidence. Already at 26 years old he was advertising in four daily papers for verifiable ‘reports on … telepathy, clairvoyance, levitation etc.’ and though he received no more than 35 not very satisfactory replies, he experienced two incidents of the kind himself.2Haynes (1983), 159.

Koestler recognized the importance of scientific methods of investigation and was ‘irritated by the blind eye turned to its results in this connection by so many academics’.3Haynes (1983), 160. He carried out informal experiments in levitation in his basement4Ward (1999), 237-39. but otherwise did little actual research.

Koestler describes this interest in his 1972 book The Roots of Coincidence (1972), which examines the idea that coincidences experienced as meaningful may not always happen by pure chance.He writes:

Half of my friends accuse me of an excess of scientific pedantry; the other half of unscientific leanings towards preposterous subjects such as extra-sensory perception (ESP), which they include in the domain of the supernatural. However, it is comforting to know that the same accusations are levelled at an élite of scientists, who make excellent company in the dock.5Koestler (1972), 11.

He recounts the ‘ascent of parapsychology towards scientific respectability’, describing his visit to the Rhine Lab at Duke University and citing advances in the study of ESP.In a chapter titled ‘The Perversity of Physics’ he attempts to clarify Heisenberg’s indeterminacy principle, comparing neutrinos with ghosts, not necessarily as a metaphor. Another chapter considers Paul Kammerer’s Lamarckian beliefs in the ‘inheritance of acquired characteristics’,6Koestler (1972), 82. citing the predisposition of both Kammerer and Carl Jung to experience meaningful coincidences. Koestler also draws attention to Wolfgang Pauli’s ‘belief in non-causal, non-physical factors operating in nature’ – namely ‘seriality and synchronicity’.7Koestler (1972), 89-90.

Koestler Foundation

In 1980, Koestler created the KIB Society together with Brian Inglis (a journalist who had written extensively on paranormal research) and Tony Bloomfield. It was renamed the Koestler Foundation following his death in 1983 and oversaw the disbursement of around £1 million, the bulk of his estate, which he directed should be used to fund parapsychological research. This eventually led to the creation of the Koestler Parapsychology Unit at Edinburgh University’s psychology department, a research organization with its own chair, where many British parapsychologists gained their PhDs.

Works (selected)

Fiction

The Gladiators (1939). London: Jonathan Cape.

Darkness at Noon (1940). London: Jonathan Cape.

Autobiographical

Spanish Testament (1937). London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Scum of the Earth (1941). New York: MacMillan Company.

Dialogue with Death (1942). New York: MacMillan Company.

Arrow in the Blue (1952, with Hamish Hamilton). London: Collins .

The Invisible Writing (1954). New York: MacMillan.

Non-fiction

Reflections on Hanging (1956). London: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

The Act of Creation (1964). London: Hutchinson.

The Ghost in the Machine (1967). London: Hutchinson.

The Alpbach Symposium 1968. Beyond Reductionism. New perspectives in the Life Sciences (1969, co-editor with J.R. Smythies). London: Hutchinson.

The Case of the Midwife Toad (1971). London: Hutchinson.

The Roots of Coincidence (1972). London: Hutchinson.

The Challenge of Chance. Experiments and Speculations (1973, with A. Hardy & R. Harvie). London: Hutchinson.

Janus: A Summing Up (1978). London: Hutchinson.

Bricks to Babel (1980). London: Hutchinson.

Kaleidoscope. Essays from Drinkers of Infinity and The Heel of Achilles (1981). London: Hutchinson.

Articles

Pavlov in retreat (1961). The Sunday Observer, 23 April.

Behold the lowly worm (1961). The Sunday Observer, 30 April.

The pioneer beyond the pale (1961). The Sunday Observer, 7 May.

Reviews of Koestler’s Books (selected)

The Ghost in the Machine (1961). Reviewed by C.I. Howarth. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 44, 401-4.

The Roots of Coincidence (1972). Reviewed by J. Randall. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 46, 91-93.

The Challenge of Chance. Experiments and Speculations (1974). Reviewed by J. Beloff. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 47, 319-26.

Bricks to Babel (1982). Reviewed by Crawford Knox. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 51, 164-65.

Kaleidoscope (1982). Reviewed by I. Grattan-Guinness. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 51, 317-18.

Melvyn Willin

Literature

Ceserani, D. (1998). Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind. London: Heinemann.

Haynes, R. (1983). Notices: Arthur Koestler C.B.E., 1905–1983. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 52, 159-60.

Ward, M.J. (1999). Review of Arthur Koestler: The Homeless Mind by D. Cesarani. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 63, 237-39.

Koestler, A. (1972). The Roots of Coincidence. London: Hutchinson.