Prominent behavioural characteristics feature strongly in some cases of past-life memory, as in the Sri Lankan case of Duminda Ratnayake. Duminda remembered having been chief monk in a famous temple and exhibited appropriate concerns and demeanour, for instance with regard to dress and religious activities. He recited stanzas in Pali, the ancient language of Buddhism that is generally only known by monks.

Contents

Overview

In early childhood, Duminda made statements about a previous life as chief monk in the famous Asgiriya temple in Kandy, about sixteen miles distant from his hometown. He also exhibited monk-like behaviours, wishing to carry his clothes as monks do, dress in monk’s clothes and be addressed as ‘little monk’. He was fond of reciting stanzes in Pali, the extinct Buddhist ritual language, and frequently expressed a wish to visit temples and become a monk.

This case was investigated by Erlendur Haraldsson and his Sri Lankan colleague Godwin Samararatne. Haraldsson reported it first in a journal paper and later in a book, I Saw a Light and Came Here, which he co-authored with James Matlock.1Haraldsson & Samararatne (1999); Haraldsson & Matlock (2016). In the early 1990s, BBC Wales made a documentary on cases of rebirth, In Search of the Dead, in which Duminda’s case was included.2 The documentary was produced by Jeffrey Iverson, in collaboration with the American CBS television network.

Duminda’s Statements

Duminda stated that he had been a senior monk (nayake-hamduruvo) or chief monk (loku-hamduruvo) at the Asgiriya Temple. With regard to his death, he said he had felt a pain in the chest and fell, then was taken to hospital, where he died. Describing this, he used the word apawathwuna, a term used only for the death of monks. He also said that:

- He had owned a red car.

- He had been teaching the apprentice monks.

- He had an elephant.

- He had friends in the Malvatta monastery and used to visit it.

He expressed a longing for the money-bag and radio he had possessed in Asgiriya. He said that after he died and before he was born again he had lived among the devas (angelic beings).

Duminda’s Behaviours

Duminda behaved in many ways consistent with the monk he believed he had been. He:

- wore and treated his clothes like a monk

- requested a monk’s robe and fan

- wanted to wear a monk’s robe (seldom allowed)

- disliked his mother calling him ‘son’ and asked to be called podi sadhu (little monk)

- expressed a wish to become a monk

- expressed a wish to visit the local vihara (place of worship)

- took wild flowers to the vihara two or three times a day on Poya-day (Buddhist monthly holiday), as monks do

- tried to build a vihara at home, like children building toy structures

- disliked killing insects or perceived wrongdoings to anyone

- often expressed a wish to go to the Asgiriya temple and the neighbouring Malvatta temple

- displayed knowledge of Pali (the ancient language of Buddhism) reciting a few religious stanzas while holding the fan in front of his face, in the monkish manner

- displayed calmness, serenity and detachment rarely found in children of his age

- did not like to play with other children

Certain incidents reinforced the perception that Duminda remembered having been a monk. For instance, he once reprimanded his mother when she wanted to help wash his hands (women are not supposed to touch a monk’s hands). On a visit to Asgiriya temple he did not want to sit down until brought a white cloth to sit on, as is customary for monks.

Duminda’s Xenoglossy

The Duminda case exhibits the rare feature of xenoglossy, utterances in a language that the speaker has never learned. He liked to recite stanzas (short religious statements) in Pali, the ancient language of Buddhism that is learned only by monks. Duminda had never learned Pali.

In the BBC documentary In Search of the Dead, Duminda was brought to a temple and asked to recite some stanzas, which he did in the presence of many monks. All the stanzas except one were recognized by the monks, and the exception was discovered after a lengthy search, inscribed in an obscure place in the Asgiriya temple.

One possible explanation for Duminda’s knowledge of the stanza was that he had been taught thems by his grandmother, but she denied that she had done so. Also, religious stanzas were recited on the national radio at 5 in the morning, although no child is known to have learned such verses in this way.

It is worth noting that when Duminda recited the stanzas he held a fan in front of his face, as monks customarily do. However, It is not known whether Duminda understood the meaning of the verses he recited.

Case Investigation

Interviews with the Family

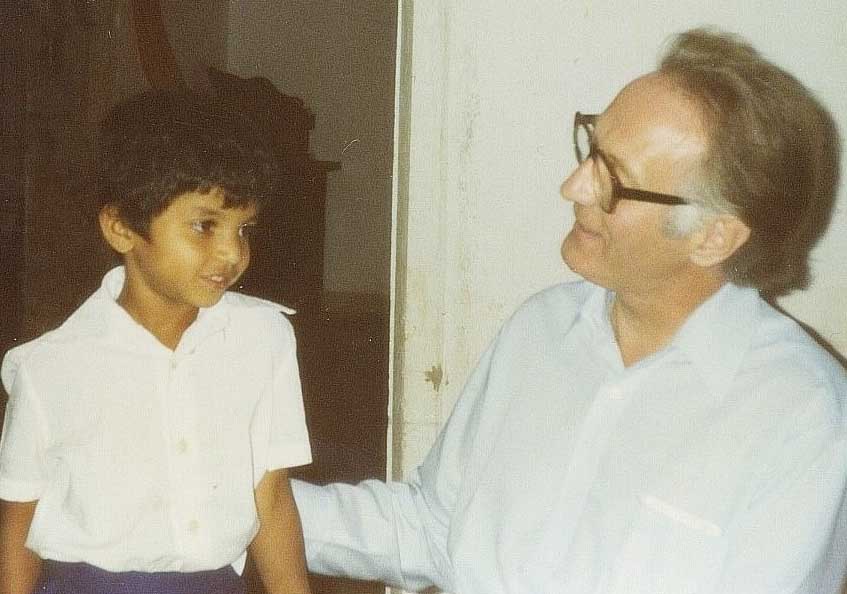

Erlendur Haraldsson learned about this case in 1988. With Godwin Samararatne he travelled to the family’s home, some sixteen miles from Kandy, and interviewed Duminda and family members. Duminda, then only four years old, was shy and did not say much. His mother, grandmother and grandfather said that since he was three, they had witnessed his extraordinary monk-like behaviour and heard him talk about his memories.

Haraldsson and Samararatne interviewed him again a year later, at which time he repeated the same statements. His mother also said that when the death of the chief monk of the Malvatta temple was announced over the radio, he told his family that he had known him. When the mother briefly left the room, the grandfather added that she had not mentioned two further statements: that Duminda had missed his radio and money-bag, items that monks are not normally allowed to possess.

Duminda’s calm detachment and dignity were evident to the investigators in comparison with his two brothers, who like normal healthy boys would never be quiet or still for long.

The family had no relative or neighbour who was a monk. There existed no ties of any kind between any member of Duminda’s family and the Asgiriya monastery. They had not visited the monastery until they eventually took the boy there in 1987, following his repeated requests. The boy’s mother had been reluctant to go there, fearing that the boy might later leave her to become a monk, as indeed he later did.

Search for the Previous Personality

A journalist from the Sri Lankan newspaper Island learned about the case and was present during Duminda’s visit to Asgiriya. He quickly decided that the boy had been referring to the Venerable Ratanapala, a senior monk who had died of a heart attack in 1975.

However, Haraldsson learned from three monks that Ratanapala had owned neither a car nor an elephant; he had no personal income, hence no money bag; he did not preach, hence did not use the fan; and he had no connection with the Malvatta monastery. Besides, Ratanapala had been known for his interest in politics. This did not fit Duminda’s statements and excluded Ratanpala as a candidate for the life Duminda was talking about.

Haraldsson needed to determine which monks:

- had income from the temple (money-bag)

- had connections with the Malvatta temple/monastery and the Temple of the Tooth (served by the Asgiriya monastery)

- had frequent occasions to visit these places

- had friends there

- had preached sermons and exhorted laymen to recite the Buddhist precepts, thus using a monk’s fan

- had often used a red car

- had a heart condition, fell down, and died in hospital

- owned a radio and an elephant

He obtained the names of all five abbots who had run the monastery in Asgiriya from the beginning of the 1920s to 1975, the year in which the abbot took office at the time he was investigating the case.

The life of the abbot Gunnepana Saranankara, who was the abbot from 1921 to 1929, fit each of the eight specific statements listed above. The chief monk (mahanayaka) of Asgiriya had owned a car and a money-bag. Gunnepana had taught other monks, had suffered a sudden pain in his chest, had fallen on the floor and been taken to hospital, where he died. He had preached, which is not the case for all monks.

Gunnepana was not thought to have actually owned either an elephant or a radio. However, Gunnepana had showed a particular interest in an elephant a disciple of his had brought to the neighbourhood. He owned a gramophone, and it is possible that this is what Duminda was remembering when he referred to a radio.

Every one of Duminda’s statements fit the life of the chief monk Gunnepanna, whereas only some fit the lives of some of the other chief monks. The conclusion seemed clear that Duminda was remembering the life of the abbot Gunnepana.

Duminda’s Later Life

In his late childhood, Duminda’s parents yielded to his persistent wish to become a monk. He entered a monastery closely associated with Asgiriya and remained there for many years, but he became very interested in computers and proficient in using them. When he was around twenty years old he left the monastery – on good terms with the residing monks – and started to work for a company that set up security cameras. Later he entered university and earned a degree in computer science. He works now for a major state institution. He is married, has a family and is an active campaigner against alcoholism among the young in Sri Lanka.

Erlendur Haraldsson

Literature

Haraldsson, E., & Samararatne. G. (1999). Children who speak of memories of a previous life as a Buddhist monk: Three new cases. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 63, 268-91.

Haraldsson, E., & Matlock, J.G. (2016). I Saw a Light and Came Here: Children´s Experiences of Reincarnation. Hove, UK: White Crow Books.