This 1960s Lebanese case of a child’s past life memories was one of the earliest investigations carried out by Ian Stevenson. He considered it one of his strongest to date, due to the quantity of verified detail and the fact that he was able to make written records of the boy’s statements before attempting to identify a previous personality. However, certain confusions with regard to the testimony, and the complexity of some of Stevenson’s arguments, made it the focus of controversy, unlike subsequent cases by Stevenson and others that have proved more robust.

Contents

Imad Elawar

Imad was born 21 December 1958 to a Druze family that lived in the village of Kornayel, near Beirut in Lebanon. As the family later described to pioneering reincarnation researcher Ian Stevenson, the first words that he spoke, between eighteen months and two years, were ‘Jamileh’ and ‘Mahmoud’. He began to speak of a previous life, saying that he had been in the Bouhamzy family and had lived in the village of Khriby (about 25 miles from Kornayel by winding mountain road). Sometimes he spoke to himself, wondering how his former associates were doing; sometimes he talked about the previous life in his sleep.

Imad repeatedly mentioned Jamileh,1Not her real name; Stevenson altered it to protect her privacy. saying she was more beautiful than his mother, also that she wore high heels and favoured red clothes. He talked about owning guns, and said he had owned a small yellow car, a bus and a truck. In particular, he described a fatal accident in which a truck had driven over a man breaking both his legs, which he considered to have been murder. He also mentioned a bus accident and expressed great joy in being able to walk.

Imad’s father scolded him for making up past-life stories, so the boy stopped mentioning them to him, instead confiding in his mother and paternal grandparents, who lived in the same house. One day, Imad was walking with his grandmother in the street when he recognized a person who was visiting Kornayel, and rushed up and embraced him: This individual turned out in fact to be a resident of Khriby (and, as was later confirmed, a neighbour known to the previous person). This convinced Imad’s parents that there might be some truth in his statements. However, they still did not attempt to verify them.

A short time later, a woman from near Khriby who was visiting Kornayel told Imad’s parents that people with the names Bouhamzy and others that the child had mentioned actually did live, or had lived, in Khriby. In December 1963 Imad’s father travelled to Khriby for a funeral, and took the opportunity to inquire further. Two men were pointed out to him; however, he made no contact with them. This event took place about three months before Ian Stevenson began his interviews.

Investigation

Stevenson first learned that there might be reincarnation cases in Kornayel from an interpreter who had worked for him, a resident of the village. Stevenson travelled to Kornayel in March 1964 and interviewed Imad, Imad’s parents and other relatives, in person, speaking in French, and via local interpreters, in Arabic. He also interviewed a member of the Bouhamzy family.

Because Imad’s family had not contacted the Bouhamzys, Stevenson was able to create a written record of Imad’s statements prior to the case being investigated, and record what happened when Imad met them. He made several further visits to Khriby and one to Raha (in Syria) for this purpose, and to carry out further interviews.

The villages are separated by a winding mountain road. Each has a bus connection with Beirut, but at this time there were no public transport links between the two villages, and there would have been little intercourse between them, apart from attendance at funerals. There was little likelihood of prior contacts between the two families and Stevenson could find no evidence of such contacts.

Stevenson included the case report in the first edition of his book Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation, published in 1966, and again, revised and expanded, in 1974.2Stevenson (1974), 270-320. Unless otherwise noted, all information in this article is drawn from this source.

Statements and Verifications

Imad’s family inferred from his statements that, in his past life, Imad had been a Mahmoud Bouhamzy of Khriby, who had a wife named Jamileh and who had been run over and killed by a truck following a quarrel with the driver. However, Stevenson soon concluded that this supposition was wrong. On his first trip to Khriby, Stevenson interviewed three people who knew the Bouhamzy family and had known Mahmoud. They confirmed that Jamileh had been his wife, but denied that he been run over by a truck; that accident had in fact happened to a different member of the Bouhamzy family, Said, in 1943. Their testimony differed from Imad’s also in other respects.

Further confusion ensued when Haffez Bouhamzy, son of Said Bouhamzy, pointed out that Said had had no connection with Jamileh, and furthermore, that a young man named Sleimann Bouhamzy, as a boy, had shown sufficient knowledge of Said Bouhamzy’s life to satisfy Said’s family that he was Said reborn, making it impossible for Imad to have been. However, Imad’s statements could be matched to the life of Ibrahim Bouhamzy, a cousin of Said’s, who had had a mistress named Jamileh (not Mahmoud’s wife) and who in his last months had lost the ability to walk due to tuberculosis of the spine, from which he died in 1949.

On a third visit to Khriby, Stevenson took Imad, his father, an interpreter and Haffez to test whether Imad, who had turned five about three months before, would recognize close associates of Ibrahim and the house in which he had lived. They travelled first to Said’s former home, where Imad showed no sign of recognizing features of the house or people in family photographs. Nor, having been taken to the place where Ibrahim had lived, did he appear to recognize either the house or Ibrahim’s mother. But that may have been because, according to the Bouhamzy family, the village had greatly changed in the fifteen years since Ibrahim’s death, and the mother had aged considerably. In other respects, the evidence was positive: he made thirteen recognitions and correct statements about Ibrahim’s life. These included the correct place in the courtyard he had kept his dog; that the dog was tied with a cord rather than the more typical chain; the correct place Ibrahim kept his gun; recognitions from portraits of Ibrahim and his brother Fuad; and a correct recounting of Ibrahim’s last words.

Of 47 items that Imad made before the first journey to Khriby, all but three proved correct (of a further ten statements that he made in the car on the way, three were incorrect.

Behaviours

From when he first spoke, Imad had a strong interest in Khriby and asked to be taken there. He threw his arms around a person whom he apparently recognized. He so longed to be with Jamileh that, at the age of three, he asked his mother to behave as if she were Jamileh.

Imad showed a phobia of large trucks and buses from infancy – part of the reason his parents had concluded he had died by being run over – but it faded completely by the time he was five. Ibrahim had been a cousin and friend of Said Bouhamzy, and Said’s death was reported to have left a great impression on him. Ibrahim had also driven a bus, and on one occasion the brakes slipped after he had stepped out, allowing the vehicle to escape down a slope and roll over, with his assistant inside it. Sleimann had a phobia of motor vehicles of all kinds that was much stronger than Imad’s, beginning to fade only when he was eleven or twelve. Stevenson noted that this difference in strength of phobias reflected the difference in emotional impact between having had a cousin and friend killed by a vehicle and having been killed by a vehicle oneself.

When Stevenson re-examined Imad’s original statements as reported by his parents, he noticed that Imad had described the truck accident but never actually said it had happened to him. According to Sleimann Bouhamzy, Said had had no quarrel with the driver, but Stevenson notes that Ibrahim was of a belligerent nature himself – as was Imad – this might have been a supposition on his part.

Similar to Ibrahim, Imad was intensely interested in hunting. Imad was precocious in school, particularly in French, even though no one else in his family could speak it; Ibrahim had been able to speak French well, having served in the French Army in Lebanon.

A reason for Imad’s early joy at being able to walk was found when Stevenson asked Haffez whether Ibrahim’s tuberculosis was of the spinal variety, and Haffez reported that it was, and had made walking difficult at first as his condition worsened and then impossible for the last two months of his life. Ibrahim’s brother did not concur that he had spinal tuberculosis, but did say Ibrahim spent the last six months of his life in hospital, bedridden much of the time.

Later Development

Stevenson visited the Elawar family in 1968, 1969, 1972 and 1973. Imad’s interest in Khriby continued unabated, and he also remained very interested in hunting, asking his father to buy him a gun. At age thirteen, he claimed he still remembered everything of his past life, and also of another life lived between Ibrahim’s death and his own birth, but did not have enough details to enable that person to be identified. Stevenson’s testing, however, suggested his memories had begun to blur.

In 1970, aged twelve, Imad met Ibrahim’s maternal uncle Mahmoud Bouhamzy for the first time. Imad did not recognize him. However when shown a photograph of him at a time when he wore a moustache, Imad said it was of ‘my Uncle Mahmoud’. Imad then spent some days with Mahmoud in Khriby, during which an incident occurred that, according to Stevenson, particularly impressed Mahmoud:

On the street one day Imad had recognized a man and he asked permission of Mr. Mahmoud Bouhamzy to talk with him. Mr. Mahmoud Bouhamzy asked Imad: “What do you want to talk to that man for? He is a former soldier”. Imad replied that this was precisely why he wanted to talk with the man. He mentioned the man’s name, but Mr. Mahmoud Bouhamzy had forgotten what the name was in 1972. Imad and the man then had a long talk and the man declared himself satisfied with what Imad told him. He confirmed to Mr. Mahmoud Bouhamzy that he and Ibrahim had entered the (French) army on the same day and had been close companions during their army service.3Stevenson (1974), 318.

Even at the age of fourteen, when reminded in conversation of the recent death of Ibrahim’s mother, Imad became tearful, showing his continuing attachment to his previous family.

Alternative Interpretation: Division and Merging of Souls?

At the time of the investigation, early in his career, Stevenson counted Imad Elawar’s case as particularly convincing because he was present and able to create a written record while the child was actively remembering, before the other family had been contacted, instead of writing long after the fact. It should be noted that this was early in his career and he did later discover stronger cases. The case of Imad Elawar, in the meantime, has generated lively debate, its complexity encouraging alternative explanations.

Parapsychologist William Roll used the case to argue against literal reincarnation of personality. In a 1977 paper discussing the true nature of personality entitled ‘Where Is Said Bouhamzy?’, he denies that personality is a fixed construct:

Personality, it seems, is more like a configuration of exchangeable parts held together by associative connections for longer or shorter periods than a solid and solitary entity. The notion of an abiding and unitary self which can be characterized in terms of certain traits or memories is not borne out by the findings.4Roll (1977), 2.

He cites a case of psychometry, suggesting that a soul has left part of itself with an object; also, experiments showing that a fear can be transferred from one animal to another, even of a different species, via a peptide extract; and an apparent mediumistic communication, complete with accurate details, from the spirit of a person who was alive and well.

Roll then asserts that in Stevenson’s cases, the deceased person tends to reincarnate in a place that is geographically close, where someone can usually be found at some degree of acquaintance with both subject and previous person. He infers from this that the memories are passed to a child via a person or an object rather than reincarnation.5Roll (1977), 2.

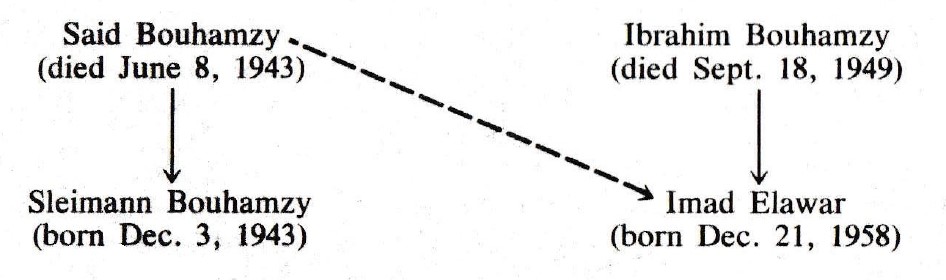

Roll elaborated on his thoughts in a 1984 letter published in the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research. Said Bouhamzy, he argued, is partly in Sleimann Bouhamzy and partly in Imad Elawar. The latter also has at least part of Ibrahim Bouhamzy in him, as illustrated by the following diagram:

The solid arrows indicate rebirth; the broken arrow indicates transfer of some memories, making this a case not only of divided rebirth (as Said split apart and went to two bodies) but merged (as Imad came from two bodies).6Roll (1984), 182-83.

Roll goes on to argue that, of 49 correct statements by Imad, no fewer than ten and as many as 44 apply to Said as well as Ibrahim, and that Imad’s phobia of vehicles is a typical feature of other cases in which the trauma happened to the subject and which Stevenson accepts as pure rebirth.7Roll (1984), 184-85.

In response,8Stevenson (1984). Stevenson notes that Ibrahim and Said were cousins living in the same village, making some similarities between their circumstances inevitable, especially with regard to names of relatives. Having quickly concluded that Ibrahim, not Said, was Imad’s previous incarnation, Stevenson had concentrated on verifications relating to Ibrahim in his publication; now checking his field notes he found at least sixteen items from both tables that applied to Ibrahim only and not Said; in short, verified information was not as evenly divided between Said and Ibrahim as Roll maintained. He also points out that a phobia can develop from an event that is not threatening or injurious to the affected person, citing a case published by Freud.

Stevenson goes on to refer to another of his reincarnation cases, that of Sujith Lakmal Jayaratne,9Stevenson (1980), 356-67. in which the child spoke obliquely of a train accident and had a mild phobia of trains, due to his past-life brother having had a train accident. He observes that both Imad and Sujith began speaking of their past lives at a very young age, when their speaking ability was rudimentary, making it easy for their parents to make incorrect interpretations.

Finally, Stevenson suggests that if, as he believes, a community’s cultural beliefs influence the way reincarnation occurs in that community, Roll would do better to seek an example of ‘soul-splitting’ in a culture that believes such a thing occurs – which the Druzes do not. However, he adds that he has never found convincing evidence of it anywhere in his reincarnation research.

Roll is supported by popular writer D Scott Rogo, who believes the ‘soul-splitting’ is the only conclusion one can reach from the evidence.10Rogo (1985), 64. Rogo interprets Imad’s early statements to indicate that he had been the man killed by the truck, and accuses Stevenson of fudging the evidence to make it look as if Ibrahim’s life alone was the precursor for Imad’s.

Reincarnation researcher James Matlock felt compelled to respond to what he called ‘egregious misrepresentations of the case’.11Matlock (1992), 91. Matlock notes that Roll repeated his interpretation of merging/division of souls, taking no account of two separate rebuttals by Stevenson, and that this was later picked up by Rogo and others, who popularized it as if it were the definitive interpretation.12Matlock (1992), 92.

Rebutting the notion of merged souls, Matlock first points out that, of 73 statements and recognitions made by Imad and tabulated by Stevenson, once the incorrect, unverified and parentally-misinterpreted ones are eliminated, fifty remain which apply to Ibrahim – plenty on which to base an identification.

He then echoes Stevenson in noting that the natures and intensities of phobias suffered by Imad and Sleimann respectively fit with their different experiences, and that Imad’s apparent confusion (in only four details) over whose life he was remembering could easily be the result of simple memory error. Matlock also issues a reminder that Imad’s delight at being able to walk does not necessarily imply he died in an accident in which both his legs were broken, as happened to Said: It could just as well be explained by the physical infirmity that prevented Ibrahim from walking in his last months.13Matlock (1992), 93-95.

Matlock finds even less evidence for Said’s soul having split, noting that most of the two boys’ memories were different, Imad’s relating to Ibrahim and Sleimann’s to Said. He also lists recognitions and behavioural differences that support separate identifications.14Matlock (1992), 97.

Alternative Interpretation: ‘Subjective Illusion of Significance’

In a 1994 article in the Skeptical Inquirer,15Angel (1994a). and again in the chapter of a book published the same year,16Angel (1994b). sceptic Leonard Angel dismisses Stevenson’s conclusions about the case, and from that the entirety of his research, based on what he considers to be fatal methodological flaws. After painstaking parsing, he accuses of Stevenson of being insufficiently rigorous in recording the information prior to verification, altering information after the fact to match the interpretation, asking at least one leading question, fudging his tabulation of statements, and more. For Angel the chief error is what he calls ‘subjective illusion of significance’.17Angel (1994b), 279.

Stevenson wrote a response in the Skeptical Inquirer, but was allowed limited space. A longer version remains unpublished.18Barros (2004).

In a later work, Angel states that Stevenson’s conclusion is in complete discord with Imad’s earliest utterances as interpreted by his parents. However, he makes no mention of Stevenson’s separation of utterances from interpretations, nor of the large number of statements, recognitions and behaviours that point at Imad’s previous incarnation having been Ibrahim.19Angel (2015), 280-82.

Angel also attempts to turn a perceived strength, written records made prior to investigation, into a weakness, claiming that identification of the previous personality was only possible by arbitrarily deciding which recorded statements to believe.

In 2004, biologist Julio Cesar de Siqueira Barros evaluated both the case and Angel’s critique of it.20Barros (2004). In this work, Barros finds fault with Stevenson’s methodology, saying it left many questions unanswered. But he points out that thirty years had passed between Stevenson’s investigation and Angel’s Skeptical Inquirer critique, and cites two subsequent papers on cases of the reincarnation type – one published in 1988 for which Stevenson is the lead author, the second by other researchers – that he judges to be of fairly good scientific quality.21The two papers are: Stevenson, I. & Samararatne, G. (1988), Three new cases of the reincarnation type in Sri Lanka with written records made before verifications, Journal of Scientific Exploration 2/2, 217-38; and Mills, A., Haraldsson, E. & Keil, H.H.J. (1994), Replication studies of cases suggestive of reincarnation by three independent investigators, Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 88, 207-19. He also exposes factual errors in Angel’s case and criticizes the Skeptical Inquirer for not allowing Stevenson to respond in full.

Barros follows with his own analysis of the case, which is arguably more painstaking even than Angel’s. He re-tabulates Imad’s statements, making his own corrections based on the case report, and limiting the statements to those made before Imad was taken to Khriby or met Stevenson, so as to eliminate the possibility of contaminated memory.

In Barros’s cautious re-analysis, 63% of the statements/recognitions are correct and 31%t incorrect, and the correct ones of a stronger nature. Far from proving that Stevenson presented an ‘unwarranted inflation of the significance of the data’, Barros argues, Angel actually provided an ‘unmerited deflation of it’. He also points out a fact that might not be obvious to Angel’s readers: that Stevenson himself thoroughly addressed weaknesses in the evidence, to the point that much of Angel’s criticism could be considered plagiaristic. The empirical evidence for reincarnation may not be particularly strong, Barros concludes, ‘but it is certainly there’.22Barros (2004).

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Angel, L. (1994a). Empirical evidence of reincarnation? Examining Stevenson’s ‘most impressive’ case. Skeptical Inquirer 18, 481-87.

Angel, L. (1994b). Enlightenment East and West. Albany, New York, USA: State University of New York Press.

Angel, L. (2015). Is there adequate empirical evidence for reincarnation? In Myth of an Afterlife: The Case Against Life After Death, ed. by M. Martin & K. Augustine, 575-83. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Barros, J.C.S. (2004). Another look at the Imad Elawar case: A review of Leonard Angel’s critique of this ‘past life memory case study’. [Web page, last modified 5 September 2012.]

Matlock, J.G. (1992). Interpreting the case of Imad Elawar. Journal of Religion and Psychical Research 15/2, 92-98.

Rogo, D.S. (1985). The Search For Yesterday: A Critical Examination of the Evidence for Reincarnation. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall.

Roll, W.G. (1977). Where is Said Bouhamzy? Theta 5/3, 1-4.

Roll, W.G. (1984). Rebirth memories and personal identity: The case of Imad Elawar. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 78, 182-86.

Stevenson, I. (1974). Twenty Cases Suggestive of Reincarnation (2nd ed., rev.). Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1980). Cases of the Reincarnation Type. Vol. III: Twelve Cases in Lebanon and Turkey. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.

Stevenson, I. (1984). Dr Stevenson replies. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research 78, 186-89.