Upton Sinclair, an American writer and political activist, wrote in Mental Radio (1930) about informal experiments in telepathy that he carried out with his wife Craig Sinclair. In these experiments, performed over a period of three years, Craig successfully reproduced drawings of objects which Upton had previously made and kept out of her sight. The book contains a short preface by Albert Einstein.

Contents

Lives

Craig Sinclair (1882–1961) was born Mary Craig Kimbrough in Greenwood, Mississippi, USA. Her father was a wealthy planter, bank president and judge. She was educated at the Mississippi State College for Women and Gardner School for Young Ladies in New York City in 1900.1Prenshaw (2009). In her early life she wrote articles for newspapers and magazines, and a book on Winnie Davis, daughter of American rebel president Jefferson Davis. Before their marriage in 1913, she and Upton Sinclair collaborated on Sylvia, a novel published the same year about a Southern girl, based on Craig’s own experiences. The couple moved to California, living together until her death in 1961.

Upton Sinclair (1878–1968) was born in Baltimore to Upton Beall Sinclair, a liquor salesman and Priscilla Hardman, daughter of a wealthy family. Largely self-taught, he achieved success as a writer from an early age, contributing to newspapers and magazines. During his life he wrote around a hundred major works of fiction and non-fiction, many of them on progressive political topics. He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1943. Some of his exposes are credited with helping to bring about significant policy changes. He ran unsuccessfully for Congress and as Governor of California.

Early Psychic Interests

Upton Sinclair became curious about paranormal phenomena after hearing a Unitarian minister assert that he had seen and spoken to ghosts. He recounts that he read hundreds of parapsychological works over a period of thirty years, while being unable completely to accept the claims. He writes: ‘The consequences of belief would be so tremendous, the changes it would make in my view of the universe so revolutionary, that I didn’t believe, even when I said I did’.2Sinclair (1930/2001), 1.

Craig Sinclair showed signs of unusual perception from childhood. For instance, she might know that her mother wanted her before being summoned, or dream the same things as her; sometimes she correctly anticipated the arrival of visitors. Shortly before the death of the writer and friend of the Sinclairs Jack London – and without direct contact – Craig was aware that he was in ‘terrible mental distress.’3Sinclair (1930/2001), 12-13.

However, for the first ten years of their life the couple paid no attention to paranormal claims. According to Upton, Craig’s early experiences of evangelical religion had made her averse to spiritual matters, and her approach to life was resolutely practical.

Craig developed health problems around age forty, apparently as a result of the stress of taking on other people’s troubles. To shield her mind from outside influences she undertook to learn mental control, investigating both orthodox and unorthodox means. At this time the couple met a young man named Roman Ostoja, a professional mind reader (referred to in Mental Radio as ‘Jan’). Ostoja in a deep trance state could anaesthetize any part of his body; he was also able to make it sufficiently rigid to bear the weight of another person on his middle while supported only by his head and feet, have a 150-pound rock on his abdomen smashed with a sledgehammer, and be buried in an airtight coffin for several hours without ill effects. Of particular interest to the Sinclairs was his demonstrated ability in a trance state to receive telepathic messages, carrying out instructions silently willed by a person nearby.

Early Experiments

The encounter with Ostoja began three years of experimentation with telepathy by Craig, which she documented in detail, as was subsequently published in Mental Radio. She began by developing a hypnotic rapport with Ostoja, commanding her subconscious mind to track his whereabouts at a given time, even if he were a hundred miles or more distant – a process she compared to trying to remember a name.4Sinclair (1930/2001), 17.

Craig increasingly found that her dreams – and sometimes even her waking thoughts – were influenced by what her husband was thinking. She took to recording these impressions before confirming them with him. On one occasion she felt inspired to write a story and then discovered it was a synopsis of a chapter from a book that Upton had just brought home but had not yet opened.

This incident prompted the couple to experiment with clairvoyance using books. Standing with her back to his bookcase – one which she did not herself use – she pulled out a volume without looking at it, then lay down and placed it on her solar plexus. She was often successful at discerning the themes of books and the cover art (the Sinclairs ensured that there was no raised lettering on the covers that she could feel with her fingers). At about the same time, she began psychically helping her husband trace lost objects such as notes and typewriter parts.

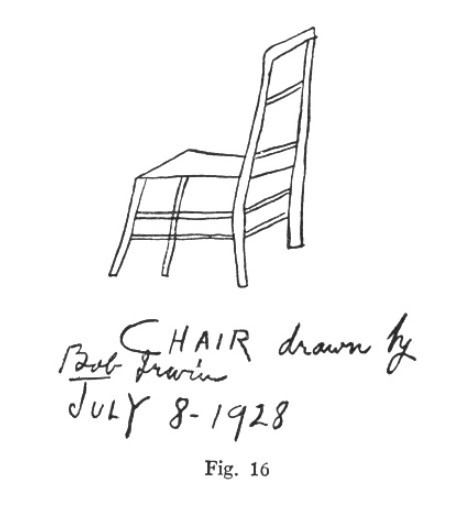

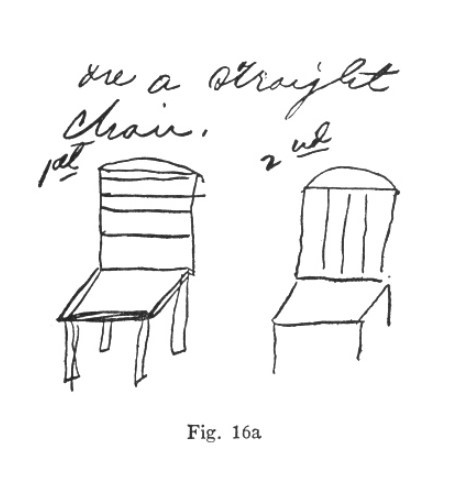

Craig also performed a distance-telepathy experiment with her brother-in-law Bob Irwin. Their homes were about forty miles apart. At an agreed time each day, Irwin made a drawing, then sat and concentrated on it while Craig ordered her subconscious mind to perceive the image. The experiment succeeded at the first attempt.

Results of Craig Sinclair and Bob Irwin telepathy experiment.5Sinclair (1930/2001), 40-41.

Especially striking in this series was Craig’s drawing of concentric circles with black spots, which to her represented blood and intense depression. Irwin too had drawn concentric circles. At the time he was preoccupied and depressed, being terminally ill and – as he later revealed – having just received bad news about the progression of his illness.

Main Experiments

Craig now asked Upton to help her with the experiments. They sat in silence in separate rooms, with a closed door between them, about thirty feet apart. Upton, or on occasion his secretary, made a drawing of any object that occurred to them.

Intially, drawings were placed in batches of sealed envelopes and laid on a table in Craig’s absence. Craig entered the room and lay on a couch, then spent some time achieving a meditative state of mental relaxation. When she felt ready she reached out to take an envelope from the top of the pile and held it in her hand above her solar plexus, waiting for an image or elements of an image to form. When it became fixed in her mind she sat up and committed it to paper. Silence was maintained until she called out that she had completed the attempt.

About halfway through the experiments, Upton decided to save time by dispensing with the envelope and instead would place the folded drawing face down on the table, out of sight of Craig, who then entered the room to start the process. (Upton denies that this might have enabled Craig to unconsciously gain sight of the drawings, adding that in any case that no increase in the number of successes was found to occur as a result.)

Craig’s observations about the processes involved are described below.

Results and Characteristics

Of a total of 290 drawings, Sinclair judged 65 (23%) to be successful matches, 155 (50%) partial successes, and 70 (24%) failures.Almost all the successes and about half the partial successes are reproduced in Mental Radio.

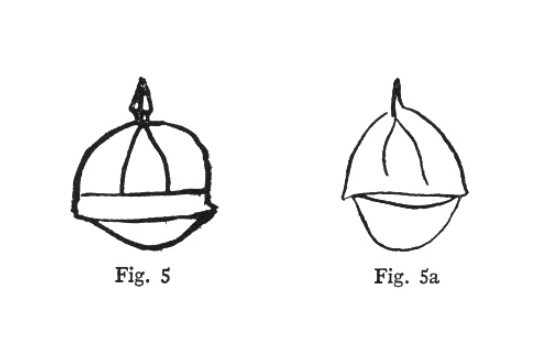

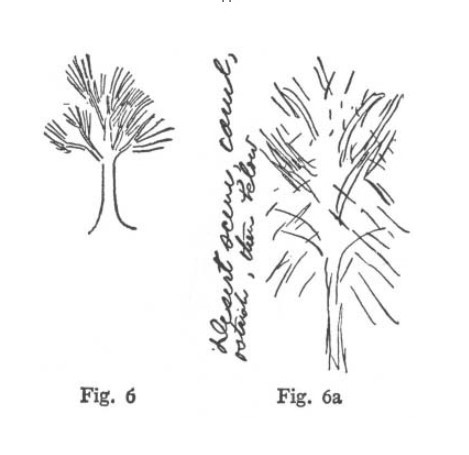

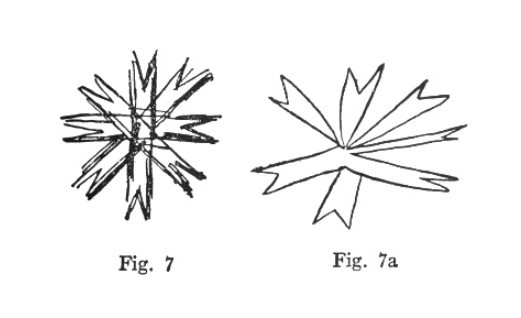

Some matches were strikingly exact. In the figures below, Upton’s original drawing is on the left, and Craig’s rendering of her telepathic perception of it on the right.

Comparative telepathic drawings by Upton and Craig Sinclair.6Sinclair (1930/2001), 13-14.

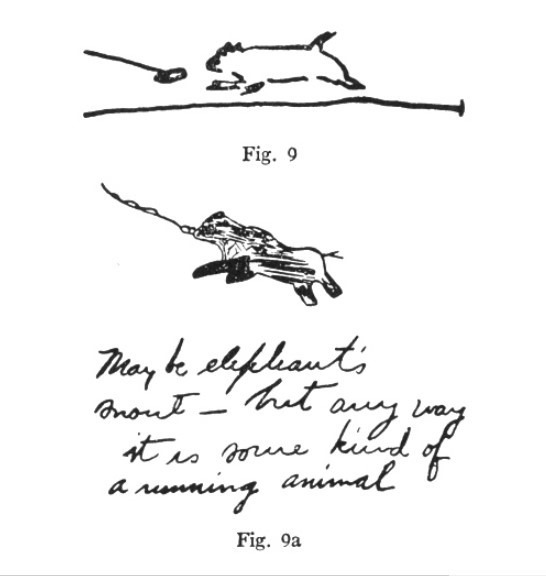

Often the shape was reproduced in outline but misinterpreted with regards to the object it represented. In one such case, a drawing by Upton of a dog chasing an object on a string was tentatively identified by Craig as an elephant’s snout, although the drawings were strikingly similar.

Comparative telepathic drawings by Upton and Craig Sinclair.7Sinclair (1930/2001), 15.

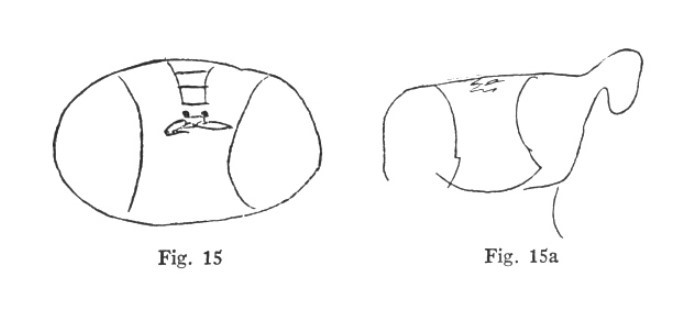

In another instance, Craig misidentified a football as a calf with a band around its belly, something she saw frequently as a child:

Comparative telepathic drawings by Upton and Craig Sinclair.8Sinclair (1930/2001), 36.

Readings were often influenced by external factors that entered either of their minds. On one occasion Upton drew a horse’s head, while Craig drew a scene she described as Oriental, with elements of white and darkness and the colors yellow and blue. This seemed a complete failure, but Craig said the mental impression had been so vivid she couldn’t believe it was wrong. It was discovered that Upton had copied the image from a Sunday supplement, on a page opposite one that contained the elements she had described.

Often Craig represented an object in fragments, for instance wheels and a horn for an automobile. Or she might add thematically-associated details, such as a Napoleon-style hat and red military coat for Upton’s image of a nineteenth-century cannon. She might also receive emotional content, for instance a sense of children playing from Upton’s drawing of a toy wagon.

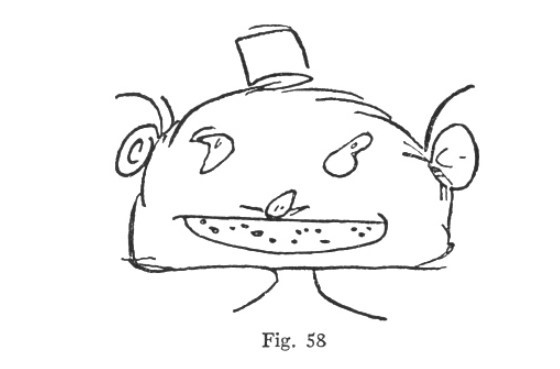

A displacement effect was observed, where Craig’s reproduction attempt failed to match the target drawing but was strikingly like another one in the same batch. Attempting to read the first of a series of eight drawings given to her in sealed envelopes, she described it as ‘some sort of grinning monster – see only the face and a vague idea of deformed neck and shoulders … the face of the creature is broad and weird’.9Sinclair (1930/2001), 62. This did not at all match the target drawing, a leg wearing a roller skate, but was a more-or-less exact description of the seventh drawing in the batch:

Target drawing.fn]Sinclair (1930/2001), 86.[/fn]

In this instance, six of the eight drawings had been made by Upton’s secretary, while the other two (without her knowledge) had been made by the secretary’s brother-in-law, who had happened to be visiting, and were the two in question, suggesting some kind of personal influence.

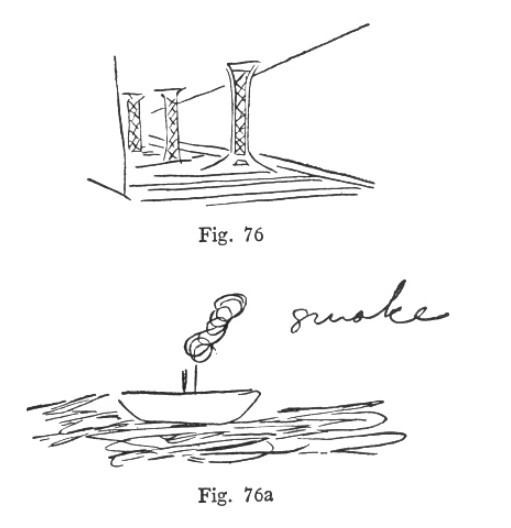

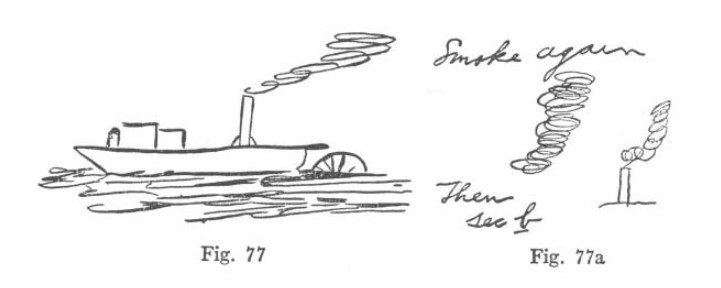

In another instance, Upton’s drawing of an elevated railway upside down was represented by Craig as a steamboat. These clearly failed to match, but she repeated elements of the same image for Upton’s next drawing in the series, which this time was actually of a steamboat:

Comparitive telepathic drawings by Upton and Craig Sinclair.10Sinclair (1930/2001), 100.

The full account, including numerous drawings, can be accessed online here.

Craig’s Technique

A chapter of Mental Radio explains Craig’s technique in her own words.11Sinclair (1930/2001), 104-14. The key, she states, is to silence all thoughts and to enter a mental state as relaxed as sleep, while remaining conscious and in control, then to give her subconscious mind the command to read.

Then, she writes,

Ask someone to draw a half-dozen simple designs for you on cards, or on slips of paper, and to fold them so that you cannot see the contents. They should be folded separately, so that you can handle one at a time. Place them on a table, or chair, beside your couch, or bed, in easy reach of your hand, so that you can pick them up, one at a time, while you are stretched out on the bed, or couch, beside them. … You must have also a writing pad and pencil beside you …

The next step, after having turned off the light and closed your eyes and relaxed mind and body full length on the couch, is to reach for the top drawing of the pile on the table. Hold it in your hand over your solar plexus. Hold it easily, without clutching it. Now, completely relaxed, hold your mind a blank again. Hold it so for a few moments, then give the mental order to the unconscious mind to tell you what is on the paper you hold in your hand. Keep the eyes closed and the body relaxed, and give the order silently, and with as little mental exertion as possible.12Sinclair (1930/2001), 107.

Craig states that fragments of forms are likely to appear first, such as a curved line, or a straight one, or two lines of a triangle. But sometimes ‘the complete object appears; swiftly, lightly, dimly-drawn, as on a moving picture film.’13Sinclair (1930/2001), 107.

These mental visions appear and disappear with lightning rapidity, never standing still unless quickly fixed by a deliberate effort of consciousness. They are never in heavy lines, but as if sketched delicately, in a slightly deeper shade of gray than that of the mental canvas. A person not used to such experiments may at first fail to observe them on the gray background of the mind, on which they appear and disappear so swiftly. Sometimes they are so vague that one gets only a notion of how they look before they vanish. Then one must ‘recall’ this first vision. Recall it by conscious effort, which is not the same thing as the method of passive waiting by which the vision was first induced. Instead, it is as if one had seen with open eyes a fragment of a real picture, and now closes his eyes and looks at the memory of it and tries to ‘see’ it clearly.14Sinclair (1930/2001), 107-8.

Walter Prince Analysis

Parapsychologist Walter Prince obtained the Sinclairs’ complete notes and drawings in order to carry out a detailed independent analysis.15Prince (1932); also Sinclair (1930/2001), 135-93. Prince agreed with Upton’s general estimate of the proportion of successes and failures, while observing that, in his view, some of the unpublished examples were better than a few that were published.

To test the possibility that close or partial matches might occur by chance, Prince carried out a control experiment. He selected the drawings made by Upton in a single particularly productive session, in which Craig successfully reproduced three, a further five being classed as partial successes, four as suggestive and one as a failure. He then recruited ten women and tasked them independently with attempting to reproduce telepathically each of the thirteen images.

Of the resulting 130 drawings, none was a successful match with the originals. There was one partial success; seven were suggestive and five slightly suggestive. The remaining 116 were failures. The objects drawn by the women were often clearly different from the target: for instance a box with an open lid was represented as a small terrier dog, a harp as a long tobacco pipe, and a rat as a four wheeled cart.

Tests by William McDougall

Psychologist and parapsychologist William McDougall, having read the manuscript of Mental Radio, visited the Sinclairs in the summer of 1930 and carried out twenty-five experiments with Craig, acting in Upton’s place as the originator of drawings.16Sinclair (1930/2001), 175-9. In most cases, the pair were either in separate locations thirty miles apart, or at opposite ends of a long room. Three of the experiments were classed as successes and four as partial successes; in addition, there was one instance of ‘anticipation’ (displacement) and two instances of suggestive similarities. A full description (without illustrations) is included in Walter Prince’s study. Prince notes that this success rate did not match the highest level of success achieved in the Mental Radio experiments but that it exceeded the lowest level. He concludes that the experiments ‘greatly transcend the expectation of chance’.17Sinclair, (1930/2001), 179.

Critical Reception

Martin Gardner

Paranormal sceptic Martin Gardner wrote about Mental Radio in his 1952 book Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science,18Gardner (1957). disputing claims of telepathy and attributing the results variously to naivete, prior knowledge, sensory leakage and selective bias.

Gardner criticizes Upton Sinclair as having been ‘a gullible victim of mediums and psychics’ throughout his life, many of his novels being ‘marred throughout by frequent intrusions of psychic matters’.19Gardner (1957), 310. He finds the paired drawings ‘strikingly similar’, but adds that it is not necessary to assume clairvoyance in order the explain them.

In the first place, an intuitive wife, who knows her husband intimately, may be able to guess with a fair degree of accuracy what he is likely to draw – particularly if the picture is related to some freshly recalled event the two experienced in common. At first, simple pictures like chairs and tables would likely predominate, but as these are exhausted, the field of choice narrows and pictures are more likely to be suggested by recent experiences. It is also possible that Sinclair may have given conversational hints during some of the tests – hints which in his strong will to believe, he would promptly forget about. Also, one must not rule out the possibility that in many tests, made across the width of a room, Mrs. Sinclair may have seen the wiggling of the top of a pencil, or arm movements, which would convey to her unconscious a rough notion of the drawing. (Many professional mentalists are highly adept at this art.)20Gardner (1957), 310-11.

Gardner goes on to suggest a selective bias as well, positing that some failures might not have been recorded (‘Sinclair is certainly capable of losing them and forgetting about them’).21Gardner (1957), 311.

William McDougall

In an introduction to Mental Radio, William McDougall writes that the experiments ‘were so remarkably successful as to rank among the very best hitherto reported’. He dismisses the idea of a hoax, considering Upton Sinclair ‘an able and sincere man with a strong sense of right and wrong and of individual responsibility’.22Sinclair (1930/2001), x.

The degree of success and the conditions of experiment were such that we can reject them as conclusive evidence of some mode of communication not at present explicable in accepted scientific terms only by assuming that Mr. and Mrs. Sinclair are either grossly stupid, incompetent and careless persons or have deliberately entered into a conspiracy to deceive the public in a most heartless and reprehensible manner.23Sinclair (1930/2001), ix-x.

McDougall adds that Craig’s description of the process concords with observations by other investigators that telepathic processes are favoured by a passive mental state.

Albert Einstein

Einstein’s short preface to Mental Radio reads as follows:

I have read the book of Upton Sinclair with great interest and am convinced that the same deserves the most earnest consideration, not only of the laity, but also of the psychologists by profession. The results of the telepathic experiments carefully and plainly set forth in this book stand surely far beyond those which a nature investigator holds to be thinkable. On the other hand, it is out of the question in the case of so conscientious an observer and writer as Upton Sinclair that he is carrying on a conscious deception of the reading world; his good faith and dependability are not to be doubted. So if somehow the facts here set forth rest not upon telepathy, but upon some unconscious hypnotic influence from person to person, this also would be of high psychological interest. In no case should the psychologically interested circles pass over this book heedlessly.24Sinclair (1930/2001), xi.

Eleanor Sidgwick

Psychical researcher Eleanor Sidgwick, an early leader of the Society for Psychical Research, reviewed Mental Radio for the organization’s journal in 1931, calling it a valuable addition to existing experimental telepathy research and noting that the Sinclairs’ results were similar to others previously published. 25Sidgwick (1931). For instance, she observes, Craig had greater success with the first three pictures of each batch, which accorded with the results of an earlier psychic, Miss Jephson, who worked with batches of five.26See Jephson (1928-1929). While the line between success, partial success and failure is by necessity subjective, Sidgwick writes, enough drawings are provided in the book to allow readers to judge for themselves.

Responses to Criticisms

Upton Sinclair writes:

My friends, both radical and respectable, must realize that I have dealt here with facts, in as patient and thorough a manner as I have ever done in my life. It is foolish to be convinced without evidence, but it is equally foolish to refuse to be convinced by real evidence.27Sinclair (1930/2001), 124.

A friend to whom he showed the manuscript could not believe that the drawings were done by telepathy, because it would mean that he was ‘abandoning the fundamental notions’ on which his ‘whole life had been based’.28Sinclair (1930/2001), 124. Sinclair responded in the book to the friend’s points, which anticipated those later made by Gardner and other sceptics.

- ‘Upton’s recall might have been influenced by his “will to believe.” ’

Sinclair comments, ‘Few of the important cases in the book rest upon my memory; they rest upon records written down at once. They rest upon drawings which were made according to a plan devised in advance, and then duly filed in envelopes numbered and dated.’29Sinclair (1930/2001), 124.

- ‘Upton lacked scientific training.’

Sinclair points out that he has had 25 years of ‘very rigid’ training in social science, having made and published thousands of investigations, ‘which were criminal libels unless they were true and exact’, yet was never once the subject of a libel suit.30Sinclair (1930/2001), 125. He adds: ‘I don’t see how scientific training could have increased our precautions. We have outlined our method to scientists, and none has suggested any change.’31Sinclair (1930/2001), 125.

- ‘Upton had shown himself to be naïve and credulous at times.’

Sinclair agrees that was sometimes the case in the past, but states he has learned by such experiences and changed. He does not see the relevance. ‘I surely know the conditions under which I made my drawings, and whether I had them under my eyes while my wife was making her drawings in another room; I know about the ones I sealed in envelopes, and which were never out of my sight.’32Sinclair (1930/2001), 125.

- ‘Craig was in poor health.’

Sinclair writes, ‘That is true, but I do not see how it matters here. She has often been in pain, but it has never affected her judgment. She chose her own times for experimenting, when she felt in the mood, and her mind was always clear and keen for the job.’33Sinclair (1930/2001), 125.

- ‘A couple are unsuitable as subjects for telepathic experiments, as they tend to think of the same thing at the same time.’

Sinclair points out that this does not explain the many successes with drawings made by people other than himself, nor Craig’s clairvoyant ability with books, also that although some of the early drawings involved familiar household objects, increasing the possibility of guesswork, many were ‘as varied as the imagination could make them’, for instance a nest full of eggs, a spiked helmet, a puppy chasing a string, and a Chinese mandarin. 34Sinclair (1930/2001), 126.

- ‘Some cases are unconvincing.’

Sinclair agrees, but argues that the collection of experiments should be taken as a whole:

Anyone who wants to can go through the book and pick out a score of cases which can be questioned on various grounds. Perhaps it would be wiser for me to cut out all except the strongest cases. But I rely upon your common sense, to realize that the strongest cases have caused me to write the book and that the weaker ones are given for whatever additional light they may throw upon the problem.’ 35Sinclair (1930/2001), 126.

With regard to suspicions about the conditions of the experiment, Sinclair asserts that he made the drawings and kept them in front of his eyes in a separate room from Craig, in such a position that she could not see them if she wanted to. ‘If I thought it worthwhile, I could draw you a diagram of the place where she sat and the place where I sat, and convince you that neither mirrors, not a hole in the wall, nor any other device would have enabled my wife to see my drawings, until I took them to her and compared them with her drawings.’36Sinclair (1930/2001), 127.

With regard to the possibility that he is perpetrating a hoax on the public, he writes that he has ‘no reason in the world’ to promote the doctrine of telepathy. ‘I don’t belong to any church which teaches telepathy. I don’t hold any doctrine which is helped by it. I don’t make any money by advocating or practicing it.’37Sinclair (1930/2001), 127.

Sinclair concludes that his publisher recommended he refrain from making protestations and assume that he would be trusted. But he says he knows the arguments ‘advanced by persons who are unwilling to change their “fundamental notions”. It seems common sense to answer here the objections which are certain to be made.’38Sinclair (1930/2001), 127.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Gardner, M. (1952/1957). Fads & Fallacies in the Name of Science New York: Dover.

Jephson, I. (1928-1929). Evidence for clairvoyance in card-guessing. A report on some recent experiments. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 38, 223-71.

Prenshaw, P.W. (2009). Sinclair, Mary Craig Kimbrough. In Lives of Mississippi Authors, 1817–1967, ed. by James B. Lloyd. Jackson, Mississippi, USA: University of Mississippi Press.

Prince, W.F. (1932). The Sinclair experiments demonstrating telepathy. Boston Society for PsychicResearch, Bulletin XVI (April), 1-86. Also in Sinclair, U. (1930/2001), Mental Radio. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

Prince, W.F. (1932). Mrs. Sinclair’s ‘Mental Radio’. Scientific American 146/3, 135-8.

Sidgwick, E.M. (1931). Review: Sinclair, Upton. Mental Radio: Does It Work, and How? Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 39, 343-6.

Sidgwick, E.M. (1932). Notes on periodicals: The Boston Society for Psychical Research, Bulletin XVI, April 1932. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 27, 293-4.

Sinclair, U. (1930/2001). Mental Radio. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

Sinclair, U. (1930/2018). Mental Radio: Does It Work, and How?[Online reproduction at Global Grey Books.]