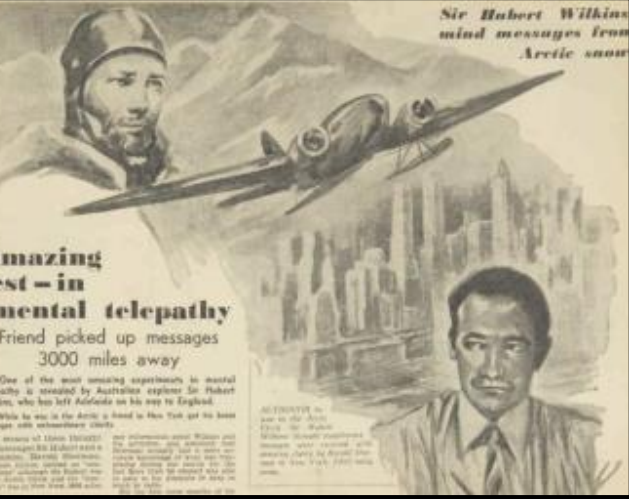

On an arctic expedition in search of missing Soviet aviators in 1938, Australian explorer Sir Hubert Wilkins conducted a long-distance telepathic experiment over a period of five months with writer and psychical researcher Harold Sherman, who was thousands of miles away in New York. Their 1942 book Thoughts Through Space describes many instances of close correspondences between Sherman’s perceptions and Wilkins’s experiences.

Contents

Experimenters

Sir Hubert Wilkins

Sir George Hubert Wilkins (1888–1958) won fame as an explorer, aviator, photographer/cinematographer and naturalist, a ‘larger-than-life’ figure whom the media closely followed.1Swann (2004). All information in this biography is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted. Born on 31 October 1888 in Mount Bryan East in southern Australia, he learned how to fly in England in 1910.2Antarctic Circle (n.d.) He worked as photographer, naturalist and leader of several polar expeditions in the Arctic in the 1920s. He was the first to fly from North America to the European Arctic, and was knighted for proving that there was no continent but only sea under the arctic ice cap. Wilkins also explored Antarctica, managing the expeditions of the explorer Lincoln Ellsworth from 1933 to 1938.

In 1937, Wilkins answered a Russian request to find Russian aviators who had disappeared in the Arctic, and it was during this project that he participated in the telepathy experiment.

During and after World War II, Wilkins served as a geographer for the British Army. He died on 1 December 1958 in Framingham, Massachusetts, USA.3Antarctic Circle (n.d.)

For more information about Wilkins including news clippings, personal writings, collections and more, see the Wilkins Foundation website here.

Harold Sherman

Harold Morrow Sherman (1898–1987) was a prolific American writer, producing books and magazine articles on various topics including sports for boys, self-help, and parapsychological research, as well as plays, some of which were performed on Broadway, and movie screenplays.4For a full list of his works, see here. He was born on 13 July 1898 in Traverse City, Michigan, USA, and was able to attend only one semester of university before World War I service called him away. Over the course of his writing career, he moved from Traverse to New York City, Hollywood, Chicago, and finally Mountain View, Arkansas, where he died on 19 August 1987. He conducted parapsychological experiments with Wilkins and astronaut Edgar Mitchell, also with JB Rhine, a leading American parapsychologist.5Haroldsherman.com (2022). All information in this biographical section is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted.

Sherman wrote that his own paranormal experiences began when he was seventeen. When he was about to turn on a light switch he heard a voice ‘in my inner ear’ saying ‘Don’t turn on the light!’several times. Shortly thereafter an electrical worker knocked on his door to warn him not to turn on any lights due to fallen high-tension lines. Thereafter he researched psi abilities and undertook to train himself to receive mental impressions and emotions telepathically.6Swann (2994), 99. He published an instructional book entitled How to Make ESP Work For You in 1965.7Sherman (1965); see review by Heywood (1965-1966).

Expedition

In August 1937, Wilkins answered a Soviet Union request for aid in locating the whereabouts of Soviet aviator Sigismund Levanevskiy and his crew, with whom contact had been lost during a flight across the Arctic basin, their last recorded position just west of the North Pole. Accompanied by a crew of two, Wilkins made four flights out of Aklavik in northern Canada between 22 August and 17 September in a long-range flying boat supplied by the Soviet government. They undertook further flights from January to March 1938 in a Lockheed Electra aeroplane equipped with skis, searching by the light of full or near-full moon, stars and aurora borealis. The missing Soviet men were never found, despite the searchers flying more than 45,000 miles.8Antarctic Circle (n.d.) The telepathy experiment was performed between the lead-up to this second series of flights, beginning in October 1937 when Wilkins headed back north to finalize his preparations, and the wrap-up of the search in late March 1938 after the Soviet government declared the search over. Levanevskiy and his crew were never found.

Experiment and Results

The experiment and its results are described in a book by Wilkins and Sherman, Thoughts Through Space, which contains the full written notes as well as records of ESP tests using Zener cards and relevant correspondence. It also has an instructional section by Sherman on how to receive telepathic messages.9Wilkins & Sherman (2004). All information in this section and the next is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted.

Sherman and Wilkins had previously known each other only casually. As Wilkins was preparing for the winter phase of the search, he met with Sherman and mentioned the risk of loss of radio contact. Sherman replied, ‘It would be great if, when you are in the Arctic, I could receive impressions from you – especially in case you are forced down, and find your radio ineffective’.10Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 9. This expanded into a protocol in which Wilkins agreed he would ‘send’ impressions each Monday, Tuesday and Thursday from 11.30 pm to midnight North American Eastern Standard Time, and Sherman at home in New York City would put his mind into receptive mode as he had trained himself to do at that same time, then record in writing the impressions he received.

As it happened, Wilkins often did not actively ‘send’ during the designated times as he was busy with evening engagements, trip preparations or the demands of the flights themselves, which entailed some danger and hence preoccupation. Nonetheless Sherman ‘received’ during every three-per-week half-hour period anyway, writing out all his impressions, for the next five months. Both Wilkins and Sherman sent all their written records as soon as they could to multiple recipients for safe-keeping and comparison, including Gardner Murphy at Columbia University.

The results were hundreds of correspondences between Wilkins’s experiences and Sherman’s impressions, including many unexpected incidents. Wilkins found that instead of receiving what he thought or felt during the half-hour, Sherman was ‘picking up impressions of practically all of my ‘strong’ or emotional thoughts in relation to the expedition matters which were expressed during various times during the day.’11Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 18. Sherman had no way of knowing what was on Wilkins’s schedule for each day, being out of normal contact for weeks at a time.

Selected correspondences:

On Tuesday 25 October 1937, Wilkins arrived in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, in the Lockheed Electra, which he enjoyed flying, to find the rest of his equipment still in crates, some not yet arrived, one crewmate unable to start due to a cold, and himself invited to give a dinner lecture such that he would be mid-speech at 11.30 pm that night. His talk was broadcast on radio and a radio announcer was to say ‘Wilkins now signing off’ for a transition from national to local broadcast, so as Wilkins awaited these words, they were in his mind.

Sherman’s impressions for 25 October were:

Trip satisfactory so far. Equipment not ready. See you break away from others.You will be late in starting.Equipment not complete. Something mechanical not arrived. You are one man short. One man has slight cold. You in company heavy-set man [sic]. You have hard time keeping appointment. Impression as if you say ‘Wilkins now signing off.’12Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 14-16.

On Thursday 11 November, Wilkins was invited to speak at a dress affair, and borrowed another man’s evening wear as he had packed none of his own. In the speech he expressed his concern that aviation might be used in war to annihilate civilians and urged more constructive use of it. Sherman’s impressions included these very points in the speech, and that Wilkins was wearing evening wear, despite the clear unlikelihood of having packed such a thing.13Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 27-29.

On Tuesday 30 November in Aklavik, in the Northwest Territories of Canada, Wilkins and his crew were invited to a party at a hospital, and his two crew members played ping pong with the nurses at a nearby school gymnasium. In his notes for that day, Sherman expressed concern that his flash impression of ‘ping pong’ might be an intrusion of memory from another event.14Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 38-39.

On Monday 6 December, Wilkins and his crew flew to a settlement called Point Barrow, which included a cluster of Inuit15Wilkins and Sherman in their narrative use the obsolete term ‘Eskimo’. tents and shacks, placed close together; the land around was Arctic tundra, mostly flat. In his Tuesday 7 December notes, Sherman described this scene well, though he mistakenly placed it in Aklavik, likely because that village was designated as the expedition base. He also accurately described the plane despite never having seen it, mentioned ‘sleeping bags of great warmth’, corresponding with Wilkins’s efforts to locally procure sleeping bags made with raindeer skin as it would be warmer than eiderdown, and a funeral service, which was accurate as a baby in the village had died.16Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 41-44.

On the Monday night, which was extremely cold, one of the Inuit homes caught fire, flames bursting out of chimney and roof, to be brought under control by the residents, men and women together, using shovelfuls of snow. Sherman’s Tuesday impressions included:

Seem to see a crackling fire shining out in darkness of Aklavik, get definite fire impression as though house burning—you can see it from your location. I first thought fire on ice near your tent built by one of crew—this may also be true—but impression persists it is white house burning and quite a crowd gathered around it—people running or hurrying toward flames—bitter cold.’17Wilkins & Sherman (2004), 42-43.

A local resident told Wilkins that in the seven years he had lived there fires were rare, making this impression unlikely to be coincidental.

Details of these and other impressions can be found here on pages 20-21.

Criticism

In a 1986 book John Booth, an American stage magician and mentalist, attaches significance to the fact that many ofthe percipient’s descriptions proved to be inaccurate, and argues that the concordances could be attributed to coincidence, the law of averages, subconscious expectancy, logical inference or a plain lucky guess.18Booth (1986), 69.

JL Woodruff judges the experiment and its book-length report as a ‘fair to middling’ contribution to the field of parapsychology’, noting that while some of the incidents of apparent telepathy are striking, no statistical evaluation was attempted by the authors and that in the comparative table of incidents and impressions, it is not always clear whether Wilkins’s entries come from his diary or later memory after reading Sherman’s letters. Woodruff also notes that it is not clear whether Sherman’s impressions as reporter are all of his impressions or a selection of the most impressive, lessening its evidential value. He also disagrees strongly with Sherman’s theory of thought transmission being a function of electrical energy.19Woodruff (1942).

RA Charman opines that the experiment should be in ‘the first chapter of any textbook on parapsychology’ but adds,‘As a personal plea, when will someone do a proper statistical analysis of the hundreds of visual and verbal impressions that Sherman obtained of what Wilkins was thinking, seeing and doing[?]’.20Charman (2014), 45.

Replication

Dale E Graff, who served as project director for the American government remote viewing programme Star Gate, attempted a replication, asking Sherman to try to receive telepathic impressions from him while engaged on a three-week canoe trip in the Canadian northwest. Graff recorded the trip in a journal, photographs and film, while Sherman notarized his impressions. Both records were sent for comparison to Harold Puthoff, a physicist involved in the Star Gate investigations. Puthoff found that Sherman had accurately perceived several unexpected turns of events including an illness that afflicted a team member, an unplanned portage, an encounter with two people and a dangerous situation, all at the time these events occurred. This was reported in a 1998 book by Graff.21Cited in Hastings (1998), 85.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Antarctic Circle (n.d.). Sample Entries for Four Explorers. [Web page; to quickly find the Wilkins biographies, page-search ‘W15’.]

Booth, J. (1986). Psychic Paradoxes. Buffalo: Prometheus Books.

Charman, R.A. (2014). Review of One Mind: How Our Individual Mind is Part of a Greater Consciousness and Why It Matters by L. Dossey. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 78/1, 44-47.

Haroldsherman.com (2022). Biography of Harold Sherman. [Web page.]

Hastings, A. (1998). Tracks in the Psychic Wilderness: An Exploration of ESP, Remote Viewing, Precognitive Dreaming and Synchronicity by Dale E. Graff [Review]. Journal of Parapsychology 62/1, 83-86.

Heywood, R. (1965–1966). Review of How to Make ESP Work for You, by H. Sherman. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 43/730, 436.

Sherman, H. (1965). How to Make ESP Work for You. London: Frederick Muller.

Stokes, D.M. (1987). Promethean fire: The view from the other side. Journal of Parapsychology 51, 249-70.

Swann, I. (2004). Foreword in Thoughts Through Space: A Remarkable Adventure in the Realm of Mind by H. Wilkins & H.M. Sherman. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads. [Originally published by C & R Anthony, Inc.]

Wilkins, H., & Sherman, H.M. (2004). Thoughts Through Space: A Remarkable Adventure in the Realm of Mind. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads. [Originally published in 1942 in New York by Creative Age Press.]

Woodruff, J.L. (1942). Review of Thoughts Through Space by H. Wilkins & H. Sherman. Journal of Parapsychology 6, 144-46.