A mind-reading act performed by a Danish-American couple Julius and Agnes Zancig won international acclaim in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Presented as a demonstration of telepathy, it is now widely assumed to have been based on a sophisticated code, following public claims to that effect by Julius towards the end of his career. However, researchers who tested the couple in their early years were unconvinced of this, noting details suggestive of genuine telepathy.

Life and Career

Julius Zancig was born Julius Jörgensen in Copenhagen on 7 March 1857.1Mulholland (1975), 211. In 1886 he married Agnes Claussen, a childhood sweetheart whom he met again when both had emigrated to the US. The couple formed a mentalist act under the stage name Zancig, performing internationally. The performance consisted of Agnes sitting or standing on stage, sometimes blindfolded and with her back turned, while Julius walked among the audience, asking for notes and objects which Agnes would then identify. The couple submitted to numerous informal tests, some carried out by psychical researchers who had knowledge of the use of codes and other conjuring techniques, without any fraudulent activity being discovered.2Baggally (1917). The act, billed as ‘Two Minds With But a Single Thought’, was hugely successful and continued until Agnes’s death in 1916.

Julius, having attempted unsuccessfully to continue performing with his second wife Ada, found other partners, first Paul Vučić (Paul Rosini), then David Bamberg, both of whom went on to develop successful careers in stage magic. In magazine articles published in 1924, Julius described a complex code that he said he and his partners relied on. Today the act is widely referenced in the stage magic community as one of consummate conjuring skill.3Mullholland (1975); See also Magicpedia here.

Julius died on 29 July 1929 in Santa Monica, California.

Testing

The Zancigs were tested informally at various times by researchers affiliated with the Society for Psychical Research, at their home, at the Alhambra theatre in London’s Leicester Square (where they frequently performed), and at other locations. Many of these tests were described by William Wortley Baggally in a 1917 book Telepathy Genuine and Fraudulent.4Baggally (1917).All information in this article is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted. He and others inclined to believe that the couple were genuinely using telepathy, since they were unable to find any indication of the use of codes and also made certain observations that they argued told against it.

The tests described by Baggally include the following:

At the couple’s apartment, with Agnes on the other side of the room and facing away, Julius chalked numbers on a slate which she immediately named in correct order. She was equally successful when Baggally himself wrote the numbers, ruling out pre-arrangement between the pair. Agnes then went to another room with the door left slightly ajar. Baggally’s wife wrote the numbers, Julius totalled them and Agnes wrote on a slate the correct result.

Julius asked Baggally to open one of two identical volumes at any page and point to a particular line. Agnes, having been given the other volume, opened it at the same page and read out the same line. Baggally commented that Julius’s only communication with her had been to call out ‘ready’, and there did not appear to have been time for the page and line number to be transmitted by means of a code.

Baggally took Julius onto the landing while the two women remained inside the room. Baggally tore a cheque out of his cheque-book and requested that Julius transmit its number to Agnes. She wrote on her slate the words ‘in the year 1875’, which was wrong.Baggally repeated the exercise with a new cheque, on which the last three digits were different from the first, while Julius remained silent. Agnes now wrote out four of the five digits in the correct order, then spoke the fifth aloud.

For a test using diagrams, Agnes sat behind a screen at the opposite end of the room from Julius and Baggally, watched by another person. Baggally presented an envelope containing cards with simple designs from which Julius pulled one and gazed at it. Agnes then drew

a diagram on a piece of paper, saying, ‘Something like half a moon.’

Drawing of a crescent moon looked at by Julius

Drawing by Agnes

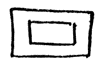

Julius drew another card from the envelope and nodded to Baggally, who called out, ‘ready.’ Agnes then said, ‘It is a square within a square.’ The diagram that Julius was looking at was this:

Agnes drew this:

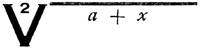

At a stage performance, Baggally handed a diagram (below) to Julius, who called out, ‘Draw this.’

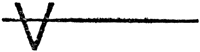

Agnes, who was on the platform, said, ‘It is something like this’ and made a motion with her right arm as if drawing a capital V. She drew it on the blackboard, then slowly drew a horizontal line through the V:

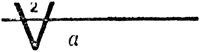

Julius said, ‘Give the number.’ She then placed a 2 in the proper position. He called out, ‘Give the rest’ at which she placed the a under the line:

Julius said, ‘What more?’ Agnes placed the plus sign correctly, but then rubbed it out as if in doubt. Finally she put down the plus sign and a capital X, so that her drawing appeared like this:

At a stage performance, Baggally handed Julius a slip of paper on which he had written a single word ‘Istapalapan’. Julius called out to Agnes, ‘spell this’, and she wrote out ‘Istapalafsan’, erroneously substituting the second ‘p’ with ‘fs’. Baggally observed that whenever Agnes made a mistake there was a similarity to the form of the letter or number to be transmitted, rather than to the sound, tending to confirm that she was telepathically seeing what Julius saw, as the couple insisted was the case, and not getting the information audibly by means of a spoken code.

Baggally drew a similar conclusion from an observation he made during an investigation by members of the SPR. Julius, in the process of selecting an object from a table, passed his hand over several other objects that had been placed there, which, without him having requested it, Agnes also proceeded correctly to name. Other researchers observed that Agnes sometimes did not name an object that Julius had selected but one lying next to it.5Echoes and News (1906).

In this context Baggally quotes an incident described by Oliver Lodge, a physicist and fellow SPR researcher. Lodge, who had earlier carried out tests with the Zancigs, noted an incident that occurred when he arrived in the middle of a stage performance, sitting with friends at the back of the gallery. Agnes was as usual naming objects that Julius was being handed by members of the audience when, apparently at the moment that Julius turned and saw Lodge, she said ‘Oliver’, without herself having seen him – as if seeing what was in his mind at that moment.6Cited in Baggally (1917), 79-80.

Baggally continued to attend stage performances by the couple, alert for patterns in Julius’s speech that would betray the use of code, but found nothing suspicious. However, he withheld a final judgement, pointing out that in all the tests he carried out, even when Julius and Agnes were separated in adjoining rooms the door was not fully closed.

Other Investigations

The Zancigs were informally tested in January 1907 by a group of SPR researchers, including Baggally. By agreement, the results were not published but were said to be sufficiently positive for a further investigation to be carried out the following July, although still on an ‘unofficial’ basis. Assessing its conclusions, the committee pointed out that the Zancigs’ performance was far in advance of anything they had hitherto seen in terms of accuracy and precision.

Further, there is, so far as we are aware, no case of any public performers (including certain recent examples) where the use of a code or apparatus has not been more or less readily discoverable or clearly to be inferred. In considering, therefore, the claim of Mr. and Madame Zancig to the possession of a genuine telepathic faculty, one is faced by the initial difficulty that such a faculty must be regarded as unique in quality, and Mr. and Madame Zancig themselves as unique in kind …. On the other hand, the difficulty of suggesting by what method, if not by telepathy, they communicate is considerable. Those who have only witnessed the public theatre performances, clever and perplexing as these are, will not appreciate how hard it is to offer any plausible explanation of their modus operandi.7Cited in Baggally (1917), 91-92.

A test was carried out at the offices of the Gramophone Company in London in February 1906, in which the couple’s questions and responses were recorded.8Echoes and News (1906). This was decided on because the rapidity of their exchanges during a performance made it virtually impossible to write them down even by shorthand; it was also thought that it would capture hesitations and vocal inflections betraying the use of a code (no mention of any such discovery was made, however). Agnes is said to have made few mistakes, also correctly identifying objects that the couple were unlikely to have seen before, such as a coloured toy cube, a patent application for a nail clipper and a double-headed ivory sculpture. In one instance, Agnes correctly named the date, number and price of a visitor’s rail season ticket, and also the name of its owner.

Use of Codes

In 1912 a pamphlet revealing codes said to be used by Julius Zancig and other mentalist performers was published in the US.9Fixen (1912). Its author Laura Fixen claimed it was written with their full cooperation and that Julius himself had taught her his system. It laid out in detail how words and phrases that Julius used when asking Agnes to name an object actually conveyed information that identified it. Every letter in the alphabet had its own cue, for instance:

I … A;

Go … B

Can … C

Look … D

Please … E, etc.

‘I want the letter’ stands for the letter ‘A’; ‘Go on give this letter’ is ‘B’ and so on. Coins could be identified as follows: ‘Here what is this’ signifies ‘money’; a phrase beginning ‘Here go’ signifies that the coin is a half-dollar; ‘Here please’ means ‘a nickel’, and so on. Names and objects could be identified by a number. Slight variations in his instructions can convey what Julius is holding – ‘I want this article’, ‘can you give the article’,’ quick the article’ signify respectively ‘a cheque’, ‘a buttonhook’ and ‘a thimble’.

These sorts of methods were used by imitators of the Zancigs and were quickly spotted by Baggally, Lodge and other investigators. Lodge described such performances as ‘exceedingly inferior’ and ‘manifestly done by a code of some kind’.10Baggally (1917), 63. In the case of the Zancigs they were ruled out in tests in which the only verbal communication between Julius and Agnes was the word ‘ready’ or where there was none at all, often even with no visual link between them.

Lodge wrote:

… I questioned Mr. Zancig about codes, and found that he was familiar with a great many. He was quite frank about it, and rather implied, as I thought, that at times he was ready to use any code or other normal kind of assistance that might be helpful, though he assured me that he found that he and his wife did possess a faculty which they did not in the least understand, but which was more efficient and quicker than anything they could get by codes.11Baggally (1917), 77-78.

However, even if Julius and Agnes relied on telepathy in their performances, it is unlikely that any of Julius’s three subsequent performing partners could have possessed the same skill. In 1924, eight years following Agnes’s death, Julius described using codes in articles in London Answers, under the headline ‘Our Secrets! Greatest Stage-Act Mystery Solved at Last’.12Price (1930), 254 n1. According to Harry Price, a British psychical researcher who claimed to have discussed the matter with Julius, the system included silent visual signals.

By a turn of the head, the movement of an eyelid, the position of a finger, a gesture, slight sounds at varying intervals, or even a pre-arranged method of breathing, the ‘agent’ (the sender of the idea) in the auditorium is able to convey to the percipient (the received, who can often seen through or under the bandage covering the eyes) on the stage the name of the object he is holding or concerning which information is required.13Price (1930), 254.

According to John Mullholland, a conjurer and author, this system was regarded as being sufficiently extensive and flexible to convey the names of objects as varied as ‘the toe of an ostrich, wood from Napoleon’s coffin, the petrified finger of a man, a glass eye, and a live snake’.14Mulholland (1975), 215.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Baggally, W.W. (1917) Telepathy: Genuine and Fraudulent. London: Methuen. [Digitized and posted by Project Gutenberg in 2021.]

Echoes and News (1906). Annals of Psychical Science 5/27, 224-26.

Fixen, L. (1912). The True Secret of Mind Reading, As Performed by the Zancigs and other Artists, including Carter the Magician and Abigail Price. Chicago: Diamond Dust.

Mulholland, J. (1975). Beware Familiar Spirits: An Investigation into Occult and Psychic Phenomena. New York: Arno Press.

Price, H. (1930). Rudi Schneider: A Scientific Examination of His Mediumship. London: Methuen.