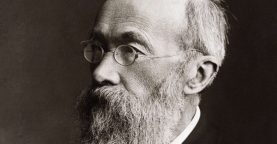

Wilhelm Wundt (1832–1920) at Leipzig University and William James at Harvard are commonly regarded as the two principal founders of scientific psychology as a modern university discipline. While James openly advocated open-minded yet scientifically rigorous studies of phenomena such as telepathy and trance mediumship and published results of his own investigations, Wundt aggressively battled belief in parapsychological phenomena, as well as their scientific study.

This article provides an overview of some of Wundt’s attacks. It concludes by considering the broadly religious motivations for his life-long fight against the paranormal, as revealed by himself in his memoirs.

Career

Born on 16 August 1823 as the son of a Protestant pastor, Wilhelm Wundt studied medicine and physiology, and occupied the chair of philosophy in Leipzig in 1875. There, he founded his famous Institute of Experimental Psychology in 1879, which rapidly became a prime place of training for the first generation of university psychologists world-wide. In the course of his long career, Wundt trained dozens of doctoral and visiting students from abroad, many of whom would later establish experimental psychology as a university discipline in their own countries.1

While versions of Wundt’s physiologically-grounded reaction-time tests came to dominate experimental psychology in German and American universities, he emphasized that laboratory work was only one half of his research programme. In order to count as truly scientific, Wundt argued, experimental psychology needed to be complemented by the study of the human mind expressing itself in history and society. The name he gave to this project was Völkerpsychologie, under which title he published ten volumes combining historical, sociological, ethnological and linguistic approaches.

Rejecting Cartesian mind-body dualism, Wundt viewed the soul as an activity or process rather than a substance. Though he believed the mental was faithfully expressed through its physiological correlates, he firmly believed the mind was an irreducible spiritual agent, and he was equally hostile to materialism as he was to the occult.2

Henry Slade

In late 1877, the prominent Leipzig astrophysicist JKF Zöllner (a friend of William Crookes) began investigating the American medium Henry Slade. Co-experimenters of Zöllner were the physicist Wilhelm Weber, the mathematician Wilhelm Scheibner, and the founder of psycho-physics, Gustav Theodor Fechner.

A senior faculty member at Leipzig university, Zöllner had previously supported the creation of a laboratory for experimental psychology and Wundt’s appointment. Probably because his indebtedness to Zöllner, Wundt accepted Zöllner’s invitation to sit with Slade in November 1877. However, he left after only half an hour.3

In one of his published reports, Zöllner had merely noted that Wundt was unconvinced by Slade’s feats. However, Herrmann Ulrici, the editor of a major German philosophy journal and supporter of scientific investigations of mediums, requested Wundt to detail his experiences with Slade, and to state the reasons for his scepticism. Although the challenge only occurred in a footnote of Ulrici’s article, Wundt used the opportunity to publicly distance his newly founded Institute of Experimental Psychology from psychical research through a widely advertised polemical response to Ulrici.4

Wundt’s pamphlet was rapidly translated into English as an article in the American Popular Science Monthly. Bypassing specific methodological critiques of Zöllner’s reports, it dismissed scientific investigations of mediums on general a piori grounds.

One of Wundt’s central points was that the only competent investigators were not scientists, but sceptical conjurors. Aware of the importance of involving trick experts, Zöllner had published a declaration by Samuel Bellachini, court prestidigitator of the German emperor, who argued that many phenomena produced by Slade could not possibly be recreated fraudulently under experimental control as applied by Zöllner and fellow investigators. Wundt, however, dismissed Bellachini’s testimony since in his view Bellachini was lacking ‘a conception of the scientific scope of this question’: If the phenomena were real, Wundt insisted, this would prove that ‘causality has a flaw and that we must consequently abandon our former view of nature’. 5

Complaining that scholars unnecessarily dignified spiritualism through serious investigations, Wundt argued that scientists should abstain from investigating mediums because of the detrimental effect of spiritualism ‘upon our moral and religious sentiment’.6 Stating the alleged spiritualist phenomena were identical with those of witchcraft, Wundt protested: ‘Phenomena hitherto regarded as lamentable expressions of a corrupting superstition are transformed into evidences of an especially gracious dissemination of supersensible mysteries.7

Continuing his juxtaposition of spiritualism with early modern witch crazes, Wundt maintained that it would be irresponsible to admit the phenomena even if they were genuine. Scientific evidence, Wundt stressed, simply did not matter: ‘The moral barbarism produced in its time by the belief in witchcraft would have been precisely the same, if there had been real witches,’ and he added: ‘We can therefore leave the question entirely alone, whether or not you have ground to believe in the spiritualistic phenomena’.8

Wundt then attacked popular notions that spiritualism was ‘a contrivance of Providence for counteracting the materialism of the present’, and he wrote: ‘I see in spiritualism, on the contrary, a sign of the materialism and the barbarism of our time. From early times, as you well know, materialism has had two forms; the one denies the spiritual, the other transforms it into matter. The latter form is the older’.9

Wundt here appropriated a theoretical framework from the fledgling discipline of anthropology. According to leading early anthropologists such as EB Tylor in Britain and Adolf Bastian in Germany, spiritualism and other beliefs in occult phenomena were signs of a relapse into ‘savage’ mental stages of development. Like Tylor, Wundt held that ‘inferior’ races were unable to form truly spiritual conceptions, and therefore conceived spirits as quasi-material entities, capable of producing effects in the physical world. If ‘superior’ races embraced spiritualism, Wundt (as well as other prominent psychologists hostile to psychical research, such as G. Stanley Hall, Joseph Jastrow, and Hugo Münsterberg) argued, this was an ‘atavism’ or symptom of mental degeneration.10

Wundt and Gustav Theodor Fechner

Wundt was a great admirer of the founder of psycho-physics, GT Fechner, who had participated in some of Zöllner’s experiment with Slade.

In response to Wundt sending him a copy of his pamphlet, in June 1879 Fechner formulated a number of criticisms of his arguments in an unpublished letter to Wundt. For instance, while agreeing regarding the ‘unedifying character of spiritualism’ as a popular religious movement and philosophy, Fechner took issue with Wundt’s dismissal of the trick expert Bellachini in favour of the phenomena:

Be candid, would you not have accepted Bellachini’s testimony if it was against Slade? If you do not accept Bellachini’s testimony, you will not, on the same grounds, accept that of any other prestidigitator, and again the same question arises which I fail to find you answering: who, then, is supposed to investigate?11

Fechner further criticised Wundt’s view that mediumistic phenomena could not be genuine because they would indicate a violation of causality or the laws of nature. Hence, Fechner wrote, he rejected the notion that because of their ‘changeableness’, the ‘spiritistic phenomena’ were ‘subject to no lawfulness whatsoever’. Again charging Wundt with bias, Fechner further wrote that ‘all your counter-arguments are, in fact, dictated by that resistance from motives which I myself share as such. Yet, how many a thing one would rather not believe in which is still proven by fact.’12

The year of his Fechner’s to Wundt also saw the publication of a book, in which Fechner commented on influential critiques of psychical research. Repeating some of the points from his letter to Wundt (without, however, mentioning him by name), Fechner protested that prominent critics overwhelmingly relied on polemics, instead of approaching the alleged phenomena in a dispassionate scientific manner.13

In 1887, the Philadelphia psychologist George Fullerton published statements by Wundt and Fechner, whom he had visited in Leipzig, on the question of the Slade experiments. According to Fullerton, Wundt stated that Zöllner had been mentally ill, and that Fechner's observations were worthless because of poor eyesight. Fullerton also claimed that Fechner told him to have observed nothing in the Slade sittings which convinced him, and that Fechner confirmed Zöllner’s unsoundness of mind.14 In response, a German psychical research journal published a letter from Fechner, in which he protested that Fullerton had severely misrepresented his statements.15

Wundt, however, continued his crusade against spiritualism and psychical research after Fechner’s death, and even tried to alter the historical record by portraying his dead mentor as a fellow sceptic.

In a speech celebrating the centenary of Fechner’s birthday in 1901, Wundt systematically downplayed his investigations into spiritualism and related areas. He insinuated, for instance, that Fechner had joined Zöllner’s investigations only reluctantly, and from Fechner’s then unpublished diaries he only selected reflections considering the possibility of Slade’s fraud. Though briefly mentioning Fechner’s unpublished letter to him in 1879 (he passed over Fechner’s published letter of protest in 1887), Wundt concealed that it was essentially a critique of his anti-spiritualism pamphlet. Moreover, by emphasizing Fechner’s dislike of spiritualism as a popular religion, Wundt obscured the fact that his teacher never ceased to confess his belief in the alleged phenomena, as is evident from Fechner’s diary, his letters to Wundt and others, and his published writings.16

Attack on Hypnotism and Psychical Research

Although variants of Wundt’s experimental psychology came to dominate Europe and the US by the 1920s, his Völkerpsychologie fell into oblivion. Moreover, outside Germany, William James, Alfred Binet, and other leading representatives of psychology took up hypnosis as a serious alternative to Wundt’s strictly physiological experimentation.17 Prominent exponents of experimental psychology especially in France – such as Charles Richet and Pierre Janet – combined hypnotic and parapsychological investigations and published experiments on hypnosis-induced telepathy and clairvoyance. They also collaborated in this field of investigation with representatives of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in England.

Leading SPR members were also involved in the formation of the International Congress of Psychology, which are still held today. These were, among others, Frederic WH Myers, Henry Sidgwick and his wife, Eleanor M Sidgwick, who represented British psychology during the first four congresses. At its inaugural session in 1889, the congress commissioned the SPR’s Census of Hallucinations, an international replication of a study on ‘veridical’ (telepathic) hallucinations, which had been pioneered by Edmund Gurney in England. In collaboration with Richet, James and others, interim reports and results of the Census of Hallucinations were presented at the international congresses of psychology between 1892 and 1896.18

The second congress was held in London in 1892, with Henry Sidgwick serving as president and Myers (jointly with the orthodox psychologist James Sully) as secretary. In anticipation of the London meeting, Wundt launched his second major onslaught on psychical research. Published as an article in his journal and separately as a pamphlet, Wundt condemned hypnotism as a form of psychological experimentation, and he attacked psychical researchers and their supporters in the fledgling psychological community.

Wundt’s first target were psychological societies in Munich and Berlin, which had been founded by figures including Carl du Prel, Albert von Schrenck-Notzing and Max Dessoir to emulate the psychical research of French and British psychologists. Next, he addressed the impending second session of the international psychology congress, protesting that, under Henry Sidgwick’s presidency, ‘clairvoyance, if not directly, but still hidden under the innocuous mask of a statistics of hallucinations’ would form ‘the main subject’ of the meeting, as had been the case with hypnotism at the first Congress in Paris.19

After scolding the doyen of French scientific psychology, Théodule-Armand Ribot, for supporting and publishing parapsychological experiments by Janet, Richet and others, Wundt accused them, without substantiating his allegations, of fundamental bias:

He who believes in it, carries out experiments in sorcery, and he who does not believe in it as a rule does not. But since man is known to have a great tendency to find confirmed what he believes in, and to this end might even apply a great ingenuity to deceive himself, to me the success of such experiments only proves that those conducting them believe in them to begin with.20

Wundt then rehearsed and expanded his claim, first made in his attack on spiritualism in 1879, of the inherent lawlessness of alleged parapsychological phenomena. As previously, he demanded that scientists should ignore these anomalies, because of the ‘results which we would have to draw from these investigations’: If Richet and Janet had reported real effects, for Wundt this only meant that ‘the world that surrounds us is assembled of two completely different worlds’. One was the ‘universe of eternally unalterable laws’, next to ‘another small world, a world of hobgoblins [Huzelmännchen] and rapping spirits, of witches and magnetic mediums’. In the latter world, ‘everything that happens in that other great and superior world is turned upside-down, all otherwise unalterable laws are occasionally put out of order on behalf of utterly ordinary and mostly hysterical persons’. Even if the effects were genuine, Wundt maintained, ‘the level-headed scientist’ was therefore still correct to pay no attention to such ‘nonsense’.21

Wundt also commented on findings by psychologists such as Janet, Binet, Dessoir, Gurney and James, who had observed divisions of personality in hypnotic subjects. Although these authors considered such findings as posing a challenge to the ‘spirit hypothesis’ in mediumship, Wundt lumped this line of research in with spiritualism. Again appropriating the anthropological standard dismissal of any open-mindedness to spiritualism as a morbid relapse into ‘savage’ mental states, Wundt characterized these investigations as ‘nothing but an atavistic residue of those age-old ideas of possession’.22

Wundt concluded his essay by stating that as ‘a cultural-historical phenomenon, occultism is certainly of no little interest’, and even ‘a captivating task of Völkerpsychologie’. Yet, he concluded, this was still no reason ‘to wish this through and through pathological line of present-day science further successes and progress’, just as it would be impermissible of a ‘physician studying with scientific interest the symptoms of disease in a patient to hope for an aggravation of the symptoms’.23

Dogmatic Mystic

Wundt has been celebrated by some historians of psychology as a hero of modern science vanquishing spiritualism and other supposed superstitions of the time.24 Others have even cited his 1879 polemic in an effort to marginalize renewed scientific evaluations of the comprehensive framework for psychology championed by William James and Frederic Myers.25

Strikingly failing to acknowledge the remarkably aggressive tone of Wundt’s polemics, this literature has also completely disregarded the wider religio-political contexts of his time. After all, Wundt’s inauguration of German experimental psychology in Prussian Leipzig coincided with a veritable war on the Catholic Church by the Chancellor of Germany, Otto von Bismarck, which was a major step towards the separation of Church and state in Germany. Like other famed German men of science with strong political leanings, such as Rudolf Virchow and Darwin’s ‘German bulldog’, Ernst Haeckel, Wundt (who had a seat as representative of the secularizing Progressive Party in the Baden State Parliament for a time) resolutely battled the political power of the Church. This they did, like Bismarck and other politicians, by utilizing a rhetoric which has equated Catholic miracle faith with corruption, bigotry, mental disease, and magical beliefs characteristic of the ‘lower races’ since the Enlightenment. Like many other eminent intellectuals of his time, Wundt feared spiritualism and psychical research might unwittingly establish tenets of ‘supernaturalist’ Catholic theology through science.26

However, Wundt’s battle was not merely political. According to his memoirs, nothing had a stronger impact on both his metaphysical convictions and his vision of psychology than a mystical experience in 1857, which, he wrote, resulted ‘in a complete reversal of my world view’.27 Following a perusal of writings by Eckhart von Hochheim and other mystics, Wundt would obtain absolute certainty that ‘the human soul in its complete purity’ was ‘perfectly one with the Godhead itself ‘.28

Though he was relatively vague on it, Wundt also revealed his fundamental belief in the immortality of the soul, whose only true notion, he insisted, was that of a perpetual state of present awareness beyond the physical categories of space and time. To Wundt, his mystical brand of immortality was therefore irreconcilable with traditional afterlife beliefs as those of Christianity and spiritualism, which he dismissed as nonsensical, crude and even materialistic. His own conception of a hereafter of the soul, Wundt emphasized, was the ‘perfect opposite’ to that other ‘vulgar immortality’, which his mystical experience had forever ‘transformed into a deceptive illusion’.29 Far from implying that he was cautious to separate his private religious convictions from his scientific work, Wundt unambiguously stated that his transformative experience and the mystical doctrines of Meister Eckhart had formed the cornerstones of his academic career.30

Andreas Sommer

Literature

Alvarado, C.S. (2017). Telepathy, mediumship and psychology: Psychical research at the international congresses of psychology, 1889– 1905. Journal of Scientific Exploration 31, 255-292.

Araujo, S. de F. (2016). Wundt and the Philosophical Foundations of Psychology: A Reappraisal. New York: Springer.

Ash, M.G., Gundlach, H., & Sturm, T. (2010). Irreducible mind? American Journal of Psychology 123, 246-50.

Blackbourn, D. (1993). Marpingen: Apparitions of the Virgin Mary in Bismarckian Germany. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Bringmann, W.G., Bringmann, N.J., & Ungerer, G.A. (1980). The establishment of Wundt’s laboratory: An archival and documentary study. In Wundt Studies. A Centennial Collection, ed. by W.G. Bringmann & R.D. Tweney, 23-57). Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Bringmann, W.G., & Tweney, R.D. (eds.). (1980). Wundt Studies. A Centennial Collection. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Fechner, G.T. (1879). Die Tagesansicht gegenüber der Nachtansicht. Wiesbaden, Germany Breitkopf und Härtel.

Fechner, G.T. (1888). (Posthum) Zöllners mediumistische Experimente. Aufzeichnungen aus dem Tagebuche. Sphinx 5, 217–221.

Gregory, F. (1977). Scientific Materialism in Nineteenth Century Germany (Studies in the History of Modern Science 1). New York: Springer.

Hübbe-Schleiden, W. (1887). Zöllners Zurechnungsfähigkeit und die Seybert-Kommission. Sphinx 4, 321-28.

Kelly, E.F., Kelly, E.W., Crabtree, A., Gauld, A., Grosso, M., & Greyson, B. (2007). Irreducible Mind. Toward a Psychology for the 21st Century. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lombroso, C. (1909). After Death—What? Spiritistic Phenomena and their Interpretation (W. S. Kennedy, trans.). London: T. Fisher Unwin.

Marshall, M.E., & Wendt, R.A. (1980). Wilhelm Wundt, spiritism, and the assumptions of science. In Wundt Studies: A Centennial Collection, ed. by W.G. Bringmann & R.D. Tweney, 158-75. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe.

Massey, C.C. (1887). Zöllner. An open letter to Professor George S. Fullerton, of the University of Pennsylvania, member and secretary of the Seybert Commission for investigating modern spiritualism. Light 7, 375-84.

Meischner-Metge, A. (ed.). (2004). Gustav Theodor Fechner: Tagebücher 1828 bis 1879 (2 vols.). Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Myers, F.W.H. (1893). Professor Wundt on hypnotism and suggestion. Mind (New Series) 2, 95-101.

Pepper, W., Leidy, J., Koenig, G. A., Fullerton, G. S., Thompson, R. E., Furness, H. H., Sellers, C., White, J. W., Knerr, C.B., & Mitchell, S.W. (1887). Preliminary Report of the Commission Appointed by the University of Pennsylvania to Investigate Modern Spiritualism in Accordance with the Request of the Late Henry Seybert. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: J.B. Lippincott Company.

Sera-Shriar, E. (2022). Psychic Investigators: Anthropology, Modern Spiritualism, & Credible Witnessing in the late Victorian Age. Pittburgh, Pennsylvania, UA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Sidgwick, H. (1892). Presidential address. In International Congress of Experimental Psychology. Second Session. London, 1892 (1-8). London: Williams & Norgate.

Sommer, A. (2013). Crossing the Boundaries of Mind and Body. Psychical Research and the Origins of Modern Psychology [PhD thesis]. University College London.

Sommer, A. (2024). James and psychical research in context. In The Oxford Handbook of William James, ed. by A. Klein, 155-76. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press (Epub ahead of print in 2020).

Sommer, A. (2025). Hidden histories of science and medicine: Spirit mediumship and the ‘psychology without a soul’. International Review of Psychiatry 37, 72-84.

Wundt, W. (1879a). Der Spiritismus. Eine sogenannte wissenschaftliche Frage. Offener Brief an Herrn Prof. Dr. Hermann Ulrici in Halle. Leipsig, Germany: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Wundt, W. (1879b). Spiritualism as a scientific question. An open letter to Professor Hermann Ulrici, of Halle. Popular Science Monthly 15, 577-93.

Wundt, W. (1892). Hypnotismus und Suggestion. Leipsig, Germany: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Wundt, W. (1894). Lectures on Human and Animal Psychology (J. E. Creighton, trans.). Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Wundt, W. (1901). Gustav Theodor Fechner. Rede zur Feier seines hundertjährigen Geburtstages. Leipsig, Germany: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Wundt, W. (1921). Erlebtes und Erkanntes (2nd ed.). Stuttgart, Germany: Alfred Kröner.

Zöllner, J.K.F. (1878-81). Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen (4 vols.). Leipsig, Germany: L. Staackmann.

Endnotes

- 1. See, e.g., Bringmann & Tweney (1980).

- 2. On Wundt’s philosophy of science and research programme, see Araujo (2016).

- 3. Zöllner (1878-1881, vol. 2, part 1), 333. For the relationship between Wundt and Zöllner, see Bringmann et al. (1980), 129.

- 4. Wundt (1879a).

- 5. Wundt (1879b), 582-83.

- 6. Wundt (1879b), 587.

- 7. Wundt (1879b), 590.

- 8. Wundt (1879b), 592.

- 9. Wundt (1879b), 593.

- 10. See, e.g., Sommer (2024). Interestingly, E. B. Tylor investigated mediums himself and, unable to explain some of the witnessed phenomena, privately considered that some of the phenomena might be genuine. He chose not to publish his observations. See Sera-Shriar (2022), chapter 2. Another major theorist of occult beliefs as ‘atavisms’ was the criminal anthropologist Cesare Lombroso, who would later convert to spiritualism (Lombroso, 1909).

- 11. Quoted in Sommer (2013), 226 (Fechner’s original emphasis).

- 12. Sommer (2013), 226.

- 13. Fechner (1879).

- 14. Pepper et al. (1887), 106.

- 15. Hübbe-Schleiden (1887). Fullerton’s chair at the University of Pennsylvania was partly funded by an endowment from the philanthropist and spiritualist Henry Seybert, who had left a bequest to the university on the condition that it should investigate spiritualism. With Fullerton as a secretary, the Commission published an entirely negative report (Pepper et al., 1887). For a penetrating criticism of Fullerton’s claims about Fechner and Wundt, see, e.g., Massey (1887), the English translator of Zöllner’s reports on the Slade experiments. Fuller was also one of many programmatically sceptical members of the original American Society for Psychical Research.

- 16. Wundt (1901), 85-90. Other excerpts from Fechner’s diaries, which tell a different story than Wundt’s selections, were first printed in Fechner (1888). His diaries were published in full much later (Meischner-Metge, 2004).

- 17. However, other early university psychologists such as the Germans Wilhelm Preyer and Hugo Münsterberg, and G. Stanley Hall in the US, joined Wundt in his polemical fight against the occult, but advocated and practised hypnotism as a form of experimental psychology. See, e.g., Sommer (2013)

- 18. On the early psychology congresses, see, e.g. Alvarado (2017), and Sommer (2013).

- 19. Wundt (1921), 8.

- 20. Wundt (1921), 9-10.

- 21. Wundt (1921), 11.

- 22. Wundt (1921), 38.

- 23. Wundt (1921), 110. In his presidential address to the congress, Henry Sidgwick briefly responded. Correcting Wundt’s claim that the Census was concerned with clairvoyance (it investigated only the role of telepathy in ‘veridical’ hallucinations), he further noted that Wundt’s polemic 'only shows that the most accomplished psychologist is liable to go rather wide of the mark, if he is determined to express his opinions on matters on which he is determined to seek no information' (Sidgwick, 1892, 2). After the congress, Frederic Myers published a reply to Wundt’s attack in the British psychology journal Mind. Expressing regret that Wundt had abused his great authority as a founder of psychology to suppress and pathologize scientific investigations of parapsychological phenomena, he concluded: 'A man must be judged by what he has himself done; – not by what he has told his neighbours that they will never succeed in doing' (Myers, 1893, 101). Wundt, however, continued his battle for the remainder of his career, e.g., in Wundt (1894, 335-36), and in his endorsement of fellow mystic Max Dessoir’s 1917 critique of occultism (see the entry on Dessoir). For a comprehensive review of Wundt’s crusade, see Sommer (2013, chapter 4).

- 24. E.g. Marshall & Wendt (1980).

- 25. Ash et al. (2010, 245), in their review of Kelly et al. (2007).

- 26. Sommer (2013, 2024). On the political nature of debates related to metaphysics, religion and the occult in contemporary Germany, see Blackbourn (1993) and Gregory (1977).

- 27. Wundt (1921), 116-17.

- 28. Wundt (1921), 118.

- 29. Wundt (1921), 118-19.

- 30. Wundt (1921), 124-25, Sommer (2025), 78.