A celebrated episode in psychical research is Professor James Hyslop’s early twentieth century study of the Thompson-Gifford case, in which a New York goldsmith was seized with an intense desire to paint in oils in the manner of a recently deceased landscape painter. A summary of the case can be found here. In this extended article, philosopher Stephen Braude considers the degree to which the case can be considered evidence of survival of death (adapted from his book Immortal Remains, 2003).

Introduction

The Thompson-Gifford case is rather difficult to classify. Although we could reasonably catalog it as an example of possession, we might also regard it as an instance of what many call obsession (the Antonia case might also fall into this category). Alan Gauld distinguishes the two sorts of phenomena as follows.

In cases of possession the supposed intruding entity displaces or partly displaces the victim from his body, and obtains direct control of it—the same sort of control, presumably, as the victim himself had…. In cases of obsession, the victim remains in immediate control of his body, but the supposed intruding entity influences his mind. It establishes a sort of parasitic relationship with his mind, whereby it can to an extent see what he sees, feel what he feels, enjoy what he enjoys, etc., and can also change the course of his thoughts and actions to conform with its own desires.1Gauld (1982), 147-48.

But how significant is this difference? Interestingly, it resembles the different degrees and types of trance found in mediumship. In both cases, the variability concerns the extent to which, and the manner in which, the intruding entity displaces the host personality. In fact, these differences also parallel some of the varying relationships between ego or personality states in cases of multiple personality/dissociative identity disorder (MPD/DID). So it is questionable whether we need to regard obsession as anything other than a type of possession. After all, we do not need to make comparable taxonomic divisions in cases of mediumship or MPD/DID. Just as mediumship and MPD/DID fall along continua of trance-depth and personality-displacement, one would reasonably expect the same to be true in cases of possession.

But this is a taxonomic side issue. A more interesting question is the extent to which a good obsession case challenges the most refractory non-survivalist counter-explanation—namely, the living-agent psi (LAP) alternative. And the Thompson-Gifford case matters because it is about as good as any real-life (rather than theoretically ideal) case gets. Predictably, the case is complex and very rich, and it can only be covered relatively briefly here.2For additional details, see the discussions in, for example, Gauld (1982); Rogo (1987); Roy (1996). The principal investigator was James Hyslop, Professor of Logic and Ethics at Columbia University from 1889 to 1902, and also one of the founders of the American Society for Psychical Research. His meticulous and painstaking account of the case consumed 469 pages in the 1909 Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research.3Hyslop (1909).

Case Details

The subject of this case was a thirty-six-year-old goldsmith from New York City, Frederic L Thompson. During an earlier apprenticeship as an engraver, he had exhibited some talent for sketching. But apart from a few art lessons during his school years, he had no formal training in art. However, throughout the summer and autumn of 1905 he often found himself seized by powerful impulses to sketch and paint in oils. These impulses began to dominate Thompson’s life, and (as his wife confirmed) during these periods he often felt that he was the artist Robert Swain Gifford. Thompson had met Gifford before, but only very casually. For example, they spoke briefly during an encounter in the marshes of New Bedford, where Thompson was hunting and Gifford was sketching. And once Thompson visited Gifford in New York to show him some jewelry. But their acquaintance seems to have gone no deeper than that, and apparently Thompson knew almost nothing about Gifford’s work.

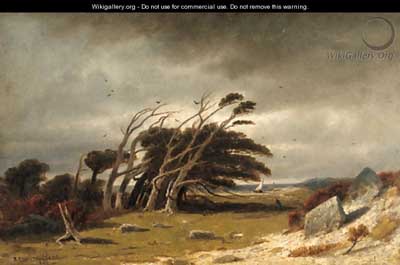

When Thompson attended an exhibition of Gifford’s work in January 1906, he learned that Gifford had died a year earlier, approximately six months before Thompson’s apparent obsession began. Moreover, as he looked at one of Gifford’s paintings, he had an apparent auditory hallucination. A voice said to him, ‘You see what I have done. Can you not take up and finish my work?’ This experience seemed only to strengthen Thompson’s urge to paint, and he began having frequent auditory and visual hallucinations. Most of the visions were of landscapes with windblown trees, and one of these haunted him repeatedly. It was a view of gnarled oaks on a promontory by raging seas, and Thompson made several sketches of it as well as a painting called ‘The Battle of the Elements’. In fact, Thompson painted several of his visions, and although opinions divided over the skill demonstrated in the paintings, he sold a few of them on their merits. Moreover, some noted a similarity between these paintings and those of Gifford.

Thompson had always been somewhat dreamy or distracted, but his current situation was more extreme. He painted in mental states ranging from slight dissociation to nearly complete automatism, and as these episodes became more common, he began neglecting his work as a goldsmith. Before long, his financial situation deteriorated badly, and both Thompson and his wife Carrie feared that he was becoming insane. So on 16 January 1907, Thompson sought advice from Hyslop, whom an acquaintance had recommended and who at first also suspected that Thompson might be insane.

Nevertheless, Hyslop was intrigued by Thompson’s obsession with Gifford. Recognizing that Thompson’s experiences resembled others in which psi apparently play a role, he decided to pursue the matter by taking Thompson to a medium. Thompson claimed to be skeptical about mediumship and spiritualism, but he was desperate enough to go along with Hyslop’s suggestion. So on 18 January they visited the medium ‘Mrs Rathbun’, to whom Thompson was introduced anonymously. Without prompting, Mrs Rathbun mentioned a man behind Thompson who was fond of painting, and her descriptions of this man resembled Gifford in several intriguing respects. Thompson remarked that he was trying to find a certain scene of oak trees near the ocean, which Mrs Rathbun then seemed to describe, noting that it needed to be reached by boat.

Both Thompson and Hyslop were encouraged by this sitting. Thompson, now feeling that he was not insane, continued to sketch and paint his visions. And Hyslop continued to arrange anonymous sittings for Thompson with other mediums. The most significant of these sittings, on 16 March 1907, was with ‘Mrs ‘Chenoweth’, one of Hyslop’s favorite mediums. Thompson entered the séance room only after Mrs Chenoweth’s trance had begun, and the session was preserved in full stenographic records. The medium’s control mentioned numerous specific items that seemed clearly to apply to Gifford, many of them subsequently confirmed by Mrs Gifford. These included Gifford’s distinctive clothing and mannerisms,4Hyslop (1909), 117, 121-22. the oil skins he wore when boating and painting,5Hyslop (1909), 126. his fondness for rugs,6Hyslop (1909), 118, 127. his color preferences,7Hyslop (1909), 119, 126-27. his love of misty scenes,8Hyslop (1909), 126. his two homes,9Hyslop (1909), 130. and his unfinished canvases.10Hyslop (1909), 124.

Mrs Chenoweth’s control also claimed to relay the following statement from Gifford: ‘I will help you, because I want someone who can catch the inspiration of these things as I did, to carry on my work’.11Hyslop (1909), 125. That statement certainly fits Thompson’s obsession, and assuming that we are dealing here with a case of possession, it is the sort of statement one might expect Gifford to convey to Thompson. But we must be careful here; the statement may instead have a more mundane origin. Earlier in the sitting, Thompson had already provided Mrs Chenoweth with enough information to concoct the statement on her own, consciously or unconsciously. When she invited Thompson to pose a question to the communicator, Thompson said, ‘Well, I just wanted to know if I should go on with these feelings that come to me and carry out the work as I feel he would like to have me’.12Hyslop (1909), 122.

A few months after this sitting, Thompson set out to locate and paint the actual scenes that had appeared before his mind, and he kept a daily diary of his efforts. But on 2 July 1907, before departing, he deposited a collection of his ‘Gifford’ sketches with Hyslop. He had drawn these in the summer and autumn of 1905, and Hyslop locked the pictures away for safekeeping, along with notations indicating how and when he received them. Thompson’s first stop was Nonquitt, Massachusetts, the location of Gifford’s summer home. Because it was inaccessible except by boat, Thompson hoped to find there some of the scenes from his visions. And in fact, he located and photographed several apparently familiar scenes. Thompson also called on Mrs Gifford, who allowed him to inspect her late husband’s studio. That studio had been disturbed very little in the two-and-a-half years since Gifford’s death, and Thompson discovered several works that seemed to be of scenes he had sketched or envisioned previously. According to Hyslop, a few of these were identical with some of Thompson’s earlier sketches.

But that alleged identity is difficult to evaluate. Not all of Thompson’s earlier sketches had been deposited with Hyslop, and Hyslop’s published photographs of Gifford pictures are sometimes small and unclear. Moreover, even when Gifford’s pictures are reproduced more adequately, it is sometimes questionable whether they correspond closely to Thompson’s sketches.13See Hyslop(1909), 385-86. However, we should also remember, as Gauld observes, that the black-and-white reproductions in Hyslop’s report may be a bit misleading. They may not do justice to similarities that would be more impressive in color.

But quite apart from these more questionable correspondences, one piece of evidence is exceptional. Thompson found on an easel a painting that matched, both closely and unmistakably, one of the sketches he had left behind with Hyslop. Because Thompson’s impulse to paint this scene first arose six months after Gifford’s death, the obvious question was whether he could have seen Gifford’s painting before producing his own sketch. To address that issue, Hyslop printed a letter from Mrs Gifford, who noted that the picture was placed on her husband’s easel only after his death. Before that it had been rolled up and put away. Hyslop also confirmed that Gifford’s painting had never been exhibited or offered for sale.14Hyslop (1909), 65ff. So Thompson had no opportunity to see the painting before this visit to Gifford’s studio.

Mrs Gifford told Thompson that he might find even more of his visualized scenes on the Elizabeth Islands, off Buzzard’s Bay, and especially on Naushon Island (where Gifford had been born). Thompson headed for those locations shortly thereafter, and he claimed to find several landscapes that matched his visions. In fact, he felt that something was directing him to the scenes. On one occasion, while sketching a group of trees on Naushon Island, he heard a voice telling him to look on the far side of the trees. There he found Gifford’s initials carved into a tree, along with the year 1902.

Also on that island Thompson located and painted the group of trees he had depicted earlier in ‘The Battle of the Elements’. Thompson had already deposited one of his initial sketches of this scene with Hyslop, and that sketch of Thompson’s vision closely matched his new painting of the scene. But of course, that proved nothing. Hyslop needed to ascertain whether the scene really existed. So he accompanied Thompson back to the island, and eventually they located and photographed the spot.15For details of the difficulties they encountered, see Hyslop (1909), 64-85. However, the photographs could only be taken from angles different from that represented in Thompson’s sketches and painting. And two of the most strikingly curved oak limbs had been broken off and were lying on the ground (Hyslop photographed these for his report). Nevertheless, it takes little effort to see that the scene corresponds quite closely to the sketch left with Hyslop. In fact, Hyslop noted that this early sketch is a more realistic depiction of the scene than the later painting, which is more idealized. Moreover, it is worth noting that in a sitting with one of Hyslop’s psychics prior to discovering the real scene, the medium predicted that one limb of the trees in question would be missing.

Thompson claimed that he had never visited these islands before his visions began. However, he had lived near the islands in his childhood. So although Thompson’s veracity generally seemed beyond reproach, Hyslop also obtained statements from Thompson’s mother, sister, and wife, confirming that Thompson had not visited the islands.

Hyslop was encouraged by these developments to arrange more sessions with his team of mediums. The new round of sittings began in April 1908, and Hyslop continued to introduce Thompson anonymously. Regrettably, nothing much of interest ‘came through’ until May 1908, by which point the press had gotten wind of this case. Although the newspaper stories were rather cursory, their appearance raises the possibility that the mediums knew enough about the case to dig up additional information on their own. There seem to be no reasons to doubt the integrity of Hyslop’s mediums. Nevertheless, because Thompson’s obsession had begun to receive public attention, we need to consider whether furtive information gathering could explain correct details revealed in the sittings. If so, that would of course detract somewhat from their impact.

For example, Mrs Chenoweth’s controls mentioned Gifford’s practice of holding something ‘like a little cigarette’16Hyslop (1909), 245. in his mouth while painting. Although Gifford did not smoke, he did hold a stick in his mouth, and he rolled it around and chewed on it as some people do with cigarettes or cigars. Now even if that habit of Gifford’s was not well-known, probably many people besides Mrs Gifford had seen Gifford paint. So many people would have been in a position to observe Gifford with the stick in his mouth, some of whom might have spoken to one of the mediums. Similar concerns apply to other details mentioned in the sittings. For example, Mrs Chenoweth also mentioned Gifford’s two studios, one in town and one in the country,17Hyslop (1909), 267. and she provided some correct details about the latter. She also correctly described, among other things, some of Gifford’s old-fashioned furniture,18Hyslop (1909), 287-88. his habit of keeping a pile of old brushes to paint ‘rocks and things that were rough’19Hyslop (1909), 289-90. and (somewhat more obliquely) the fact that Gifford had lost a child whose face he tried to incorporate into his pictures.20Hyslop (1909), 309. That last item seems less likely than the others to have been known beyond Gifford’s most intimate acquaintances. But it was probably no secret, and probably many people knew that Gifford had lost two sons.

Of course, the strength of this case does not rest on the later sittings. So even if we can explain some of the material from those sittings by appealing to one or more of what Braude called the Usual Suspects (dissociation, latent abilities, hidden memories), that strategy will not work for the earlier sittings, and it certainly will not help account for the similarities between Thompson’s sketches and Gifford’s paintings.

Another intriguing incident comes from a sitting with Mrs ‘Smead’ (also a trance medium) on 9 December 1908. Gifford purported to control the medium, drawing what looked like a cross on top of a pile of rocks, and then writing that his name was on the cross. Interestingly, Thompson had encountered such a cross near the sea, one month before this sitting. The cross was part of a wrecked ship, and although Thompson thought he saw Gifford’s initials RSG on the cross, they disappeared as he approached. However, the scene impressed him so much that he painted it. He also described the incident in a letter to his wife, which Hyslop obtained prior to the 9 December sitting.

Evaluation

Overall, this case is undoubtedly impressive, and it poses a clear challenge to the living-agent-psi hypothesis. Nevertheless, partisans of living-agent psi can raise legitimate concerns. First, there are the usual worries about the subject’s ESP. Could Thompson have clairvoyantly ‘viewed’ Gifford’s original works, and could he then have painted his resulting visions? Moreover, although some of Thompson’s sketches are strikingly close to Gifford’s pictures, others are less so. In fact, some seem to represent fairly generic New England landscapes. So it is unclear how much psychic functioning Thompson’s sketches and paintings represent, and perhaps this case does not challenge us — as the best mediumistic cases do — to explain highly prolific and consistent psychic functioning.21For a discussion of the major challenges posed by long-term successful mediumship, as in the case of Mrs Piper, see Braude (2003).

Similarly, one might question the amount and quality of psi demonstrated by Hyslop’s mediums. Although several mediums provided nuggets of correct and occasionally obscure information about Gifford, these did not occur with the impressive regularity found in the very best mediumistic cases. It is also curious that none of Hyslop’s mediums managed to come up with Gifford’s name, although Mrs Smead came up with the initials RSG (after first producing them as RGS). That seems puzzling on both the survivalist and LAP hypotheses. If the mediums could get other fine details, either from the deceased Gifford, Mrs Gifford, Thompson, or Hyslop, why not Gifford’s name?

Moreover, we need to look closely at the relationship between Hyslop and his mediums. Consider, first, Mrs Chenoweth. Although we are probably entitled to regard her as being a good psychic, this case and the somewhat notorious Cagliostro case22See the discussion in Braude (2003) and Eisenbud (1992). (and perhaps others) suggest that she may have been more thoroughly ‘tuned’ to the living than to the dead. In particular, Mrs Chenoweth may have been unusually sensitive to Hyslop’s unspoken needs and interests. Therefore, since experimenter (or sitter) influence cannot be ruled out, one must consider the possibility that Hyslop’s knowledge of Gifford contributed to the verifiable portions of the mediumistic communications. And of course, other parts, beyond Hyslop’s knowledge, could be attributed to the medium’s ranging ESP of other sources, such as Mrs Gifford and (especially in the later sittings) Thompson.

Furthermore, the relationship between Hyslop and Mrs Smead only fuels this sort of concern. Before Hyslop’s involvement with this medium, none of her mediumistic productions were remotely evidential. Once again, Hyslop seems to have been a catalyst for apparently evidential communications. All this suggests either outright experimenter psi, or some other sort of medium-experimenter psychic interaction. Moreover (as already noted), we cannot rule out psychic interaction between the medium and Mrs Gifford or Thompson. For example, the incident mentioned above, about the hallucination of Gifford’s initials on a cross, could be explained in terms of telepathy between Mrs Smead and either Thompson or Hyslop. And of course, since Mrs Gifford confirmed the various details about her husband’s habits, clothing, favorite locations for painting, and so forth, she might have been a prime target for psychic snooping.

Another troubling feature of the Smead sittings is that Hyslop helped this medium by allowing her to handle Gifford’s brushes. Now there is plenty of anecdotal evidence, and some experimental evidence, that psychometry is possible. That is, we have good reason to believe that handling a person’s objects helps some psychics home in on relevant facts about those objects or about the person’s life.23See, for example, Besterman (1933); Dingwall (1924); Osty (1923); Pagenstecher (1922); Pollack (1964); Prince (1921). For the moment, it does not matter how we explain that phenomenon. And for reasons having to do with the alleged unintelligibility of the concept of a memory trace,24Braude (2014), chapter 1; Bursen (1978); Heil (1978); Malcolm (1977). we can perhaps rule out one leading theory: namely, that information is impressed or encoded into the psychometric object. What matters here is that however psychometry works, survivalist conjectures are gratuitous or irrelevant. Whatever the mechanism for psychometry may be (if there is one),25For a discussion of the pitfalls of mechanistic explanations in parapsychology, see Braude (1997; 2014). it seems clear enough that the psychometric object plays a crucial role. Somehow, it enables the psychic to focus or pick out verifiable bits of information. So when psychometry is practiced successfully on objects belonging to the living, presumably our explanations do not require appealing to postmortem entities. But then we do not obviously need to do so when the objects in question are those of dead people. So it is far from clear that Mrs Smead’s verifiable remarks when handling Gifford’s brushes require us to posit Gifford’s survival.

Of course, living-agent-psi explanations must do more than indicate how psi among the living might create the appearance of postmortem survival. They must also indicate why. They must posit a plausible underlying motivation for simulating survival. In correspondence with David Scott Rogo over an early draft of Rogo’s book The Infinite Boundary, Jule Eisenbud attempted such an explanation.26Rogo (1987),272-74. Eisenbud’s conjecture is based in part on his interpretation of Thompson’s interactions with Gifford. Thompson himself admitted that after meeting Gifford in New Bedford he made a ‘few attempts at art work’.27Hyslop (1909), 30. But, he writes, ‘beyond the copying of prints my efforts were so crude and laborious I soon gave it up’.28Hyslop (1909). Thompson also claimed that Gifford did not encourage painting as a profession, but that he did take an interest in his metalwork and spoke of its artistic possibilities. Later, when he called on Gifford in New York, Thompson says Gifford did not recognize him at first, and (apparently mistaking Thompson for an artist) he spoke of how difficult it was for an artist to succeed in New York. He then encouraged Thompson to pursue his activities in glass and metalwork.29Hyslop (1909), 31.

Now it is unclear whether Thompson idolized or even respected Gifford as a painter before his obsession began. According to Thompson, he had seen only one of Gifford’s paintings before his fateful visit to the gallery (one year after Gifford’s death), and he claims that he did not particularly like that painting. We cannot know whether this disavowal is sincere or self-aware, but if we consider, reasonably, that it is not, then Gifford’s later remarks to Thompson might have been taken as a kind of slap in the face. They might have struck Thompson as a refusal to encourage him as a painter, capped by a dismissive suggestion to stick to his metalwork. If this interpretation of events is plausible, then Eisenbud’s proposal needs to be taken seriously. He wrote,

These slights may appear to be meager enough data upon which to base a serious supposition concerning the underlying dynamics of the Thompson-Gifford case. However, psychiatrists regularly see the far-reaching and sometimes quite astonishing effects of what might superficially seem to be slight enough rejections. If in fact Gifford had become a kind of admired ideal image for the youthful Thompson, a target for unconscious identification—and we are certainly not postulating in this anything at all uncommon between a young man aspiring to a vocation and an older one with considerable gifts along the lines aspired to—such treatment could be crushing. On one hand it might well have resulted in what might superficially appear to have been a complete withdrawal of interest on Thompson’s part in Gifford’s subsequent life and work. (There is some ambiguity on this point, but there were several years during which Thompson is alleged neither to have sought nor to have had any further contact with Gifford, not even learning of his death until almost two years [sic] after it had occurred.) But it could at the same time have resulted in a compensatory strengthening of the unconscious bonds of identification with Gifford. This would have amounted to an unconscious attempt to capture and hold the rejecting ideal figure through a kind of psychic incorporation, which psychiatrists commonly see in similar situations. And this could well have led ultimately to a delusion on Thompson’s part that Gifford’s spirit had actually invaded and informed his own by way of singling him out to be the vehicle for continuing his work.

This type of feeling-idea is consistent with a wide range of phenomena commonly seen when people feel rejected or abandoned by someone whose love and appreciation they desire. It is perhaps most often—in fact classically—seen in the subtle kinds of identifications which develop during and after mourning for a love object lost through death or other type of desertion.30Rogo (1987), 273.

Apparently, then, both the survival and LAP hypotheses can account for the motivations behind Thompson’s obsession and paintings. Survivalists would appeal to Gifford’s intense desire to complete the work he left unfinished. And they could claim that Gifford selected Thompson as his medium because of Thompson’s native artistic abilities and perhaps also (as Rogo suggests, partly in the spirit of Eisenbud) because Thompson ‘was both psychically and psychologically bonded’ to Gifford.31Rogo (1987), 275. Anti-survivalists could claim that Thompson’s paintings resulted from (in Eisenbud’s words) ‘a natural, if psi-mediated, projection of Thompson’s unconscious fantasy… [rather] than… a kind of emanation from someone who in life found Thompson uninteresting both as a person and as an aspiring painter.32Rogo (1987), 274.

But even if we go along with Eisenbud, partisans of living-agent psi must still explain the clear correspondence between some of Thompson’s sketches and Gifford’s works. In fact, that may be the most intransigent feature of the case, from any point of view. We can probably sidestep the issue of the apparently anomalous skill demonstrated by Thompson. Although Thompson was not a trained artist, he was clearly an artistic person, and he had previously demonstrated skill in sketching. But (leaving aside the clearly untenable hypotheses of fraud or coincidence) how should we explain the best of the correspondences?

At this point, partisans of living-agent psi have two broad explanatory options. On the one hand they could adopt what Braude called a ‘multiple-process’ explanation, positing a sequence of relatively minor psi tasks strung together (a little telepathy here, a little clairvoyance there, and so on). Or, they could adopt what Braude (following Eisenbud) called a ‘magic wand’ explanation positing a direct, unmediated and unimpeded link between an efficacious wish and a macroscopic result (that is, without an underlying series of causal steps).33See Braude (2003) for a discussion of these options.

Thus, a multiple-process LAP explanation would probably posit something along the following lines. Thompson might have (a) acquainted himself clairvoyantly with Gifford’s works and sketched directly from those clairvoyant impressions, or (b) ‘learned clairvoyantly (perhaps from Mrs Gifford) of Gifford’s favourite hunting grounds, clairvoyantly investigated them, and selected from them, as the themes of recurrent visions, the sorts of spots which might appeal to a painter’.34Gauld (1982), 154. And presumably a magic-wand explanation would claim that Thompson required no psychic search procedures at all, either for Gifford’s works, Mrs Gifford’s mental clues, or Gifford-friendly scenes along the coast. The required images would simply be there in his mind, given (a) the appropriate needs and desires, and (b) a confluence of psi-conducive background conditions allowing this to occur (rather than being extinguished in the crossfire of other under-the-surface crisscrossing causal chains). And then, to explain Thompson’s other psychic experiences (for instance, during island expeditions to locate scenes from his visions), the magic-wand explanation would posit timely additional spurts of clairvoyance.

Undoubtedly, some will dismiss both types of LAP explanation as wildly incredible. But in fact, survivalists may not be able to take that position. They too must posit a rather amazing psychic achievement to explain the correspondences, and arguably it is no less super and no less incredible than whatever the LAP hypothesis requires. Let us grant, reasonably, that Thompson had no normal knowledge of the Gifford works he replicated. In that case, survivalists must suppose either (a) that the surviving Gifford repeatedly and successfully telepathically supplied Thompson with detailed information about those works, and that this allowed Thompson to construct sufficiently detailed visions from which to sketch and paint, or (b) that the surviving Gifford (psychokinetically or telepathically) controlled Thompson’s body and mind to produce the needed visions and to guide his hand with exquisite refinement in the production of the sketches and paintings.

Conclusion

So as far as the correspondences are concerned, one could argue that there is no clear reason to prefer either the survivalist or LAP explanation. Neither seems conspicuously simpler or antecedently less incredible than the other. Nevertheless, it is not unreasonable to give the survival hypothesis a slight edge here, especially if we decide that Thompson’s paintings correspond consistently to those of Gifford. In that case, the consistency of Thompson’s mediumistic achievement is another crucial datum in need of explanation, and it is precisely on that point that LAP explanations may falter, suffering from what Braude called the problem of crippling complexity.35Braude (2003).

Indeed, when we look at the case as a whole and recognize that Thompson’s achievements have to be explained along with the material gleaned from several mediums, crippling complexity seems clearly to be an issue. Gauld expressed a similar point when he wrote that the super-psi (that is, LAP) hypothesis, ‘applied to this case… is messy in a way not to be equated with mere complexity. If the survivalist theory were tenable it would immensely simplify things.36Gauld (1982), 155. On the LAP hypothesis, the evidence needs to be explained in terms of the psychic successes of, and interactions between, many different individuals. And it must also posit multiple sources of information, both items in the world and different people’s beliefs and memories. But on the survival hypothesis, we seem to require fewer (and fewer distinct kinds of) causal links and one individual — a surviving Gifford — from whom all the needed information flows.

Stephen Braude

Literature

Besterman, T. (1933). An experiment in ‘clairvoyance’ with M. Stefan Ossowiecki. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 41, 345-52.

Braude, S.E. (1997). The Limits of Influence: Psychokinesis and the Philosophy of Science (rev. ed.). Lanham, Maryland, USA: University Press of America.

Braude, S.E. (2003). Immortal Remains: The Evidence for Life after Death. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Braude, S.E. (2014). Crimes of Reason: On Mind, Nature & the Paranormal. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bursen, H.A. (1978). Dismantling the Memory Machine. Dordrecht, Boston, London: D. Reidel.

Dingwall, E.J. (1924). An experiment with the Polish medium Stefan Ossowiecki. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 21, 259–63.

Eisenbud, J. (1992). Parapsychology and the Unconscious. Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books.

Gauld, A. (1982). Mediumship and Survival. London: Heinemann.

Heil, J. (1978). Traces of things past. Philosophy of Science 45, 60-72.

Hyslop, J.H. (1909). A case of veridical hallucinations. Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 3, 1-469.

Malcolm, N. (1977). Memory and Mind. Ithaca, New York, USA: Cornell University Press.

Osty, E. (1923). Supernormal Faculties in Man. London: Methuen.

Pagenstecher, G. (1922). Past events seership: A study in psychometry.’Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 16, 1-136.

Pollack, J.H. (1964). Croiset the Clairvoyant. New York: Doubleday.

Prince, W.F. (1921). Psychometric experiments with Señora Maria Reyes de Z. Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research 15, 189-314.

Rogo, D.S. (1987). The Infinite Boundary: A Psychic Look at Spirit Possession, Madness, and Multiple Personality. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

Roy, A.E. (1996). The Archives of the Mind. Essex, UK: SNU Publications.