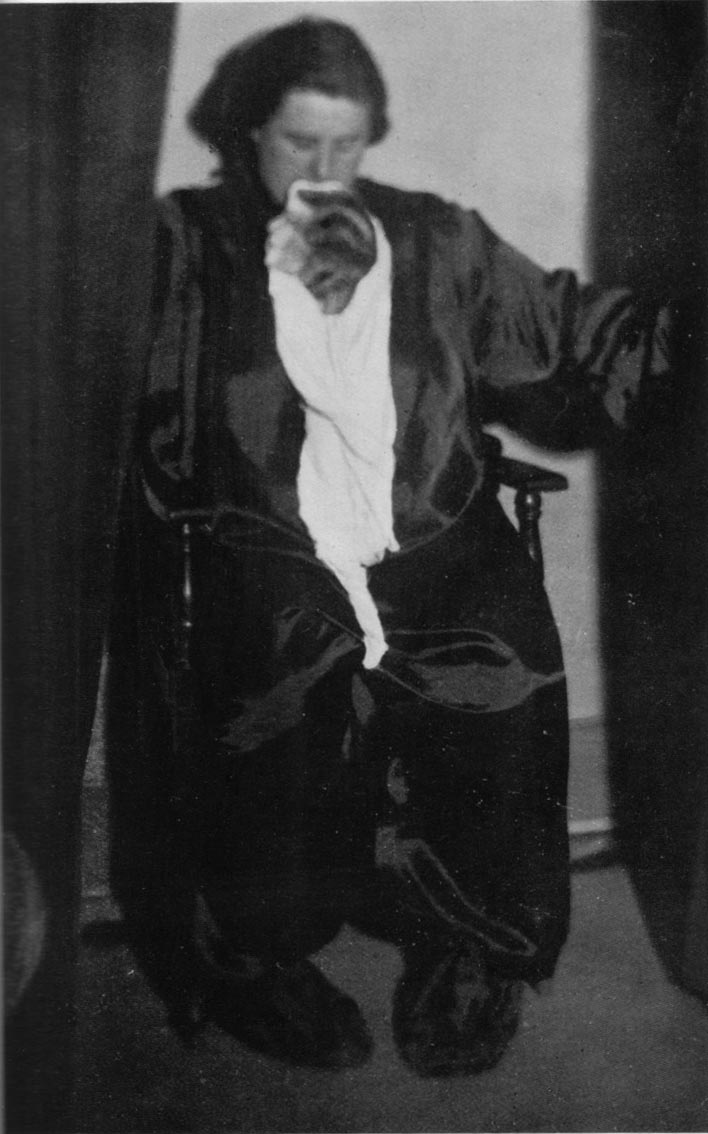

Helen Duncan (1898–1956) was a Scottish physical medium who was active in the early-to-mid twentieth century. She was best known for production of ‘teleplasm’ (more commonly called ‘ectoplasm’, a supposedly spiritual substance, and materializations of spirits, usually the sitters’ deceased loved ones. Investigations suggested that these phenomena were at least partly illusions created by the use of cheesecloth or other common materials. Duncan was prosecuted and handed a jail sentence, one of the last people to be convicted under England’s Witchcraft Act of 1735.

Contents

Background

Victoria Helen McCrae MacFarlane was born in Callander, Perthshire, Scotland, on 25 November 1898. She was one of eight children of a master slater, Archibald MacFarlane, and his wife Isabella. Helen was said to show psychic ability from a young age, for instance warning people of dangers that later came to pass.1Hahn, (n.d.-a). All information in this section is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted.

Aged sixteen Helen started working in Dundee, first in a munitions factory and later as a nurse. She married Henry Duncan on 27 May 1916 (both claimed to have had an earlier vision of the other). Henry was invalided out of the army with rheumatic fever and became a cabinet maker until ill health forced him out of fulltime work. The couple had twelve children, only six of whom survived infancy. Helen worked part-time at a bleach mill. Henry encouraged her to develop her psychic talents, which family history states included ‘the gift’ on the part of female relatives on both sides, in the forms of clairvoyance, clairaudience, psychometry and precognition.

While she was in a state of deep trance, the voice of a ‘Dr Williams’ told Henry his wife was capable of materializing spirits, and with her husband’s encouragement she began holding experimental sittings. By the mid-1920s the couple were receiving requests for sittings from all over the country, many of which were recorded in the London Spiritualist journal Light.

Mediumistic Sittings

As was generally done in physical mediumship, sitters were seated in a single or double crescent in front of a ‘cabinet’, a curtained-off corner, in which the medium sat.2West (1946), 34. All information in this and the next section is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted. Low visibility was provided by red light. Duncan was stripped, searched, dressed in specially-designed garments intended to rule out trickery and led to her chair in the cabinet. Henry was usually at the back of the room.

Helen entered a trance and soon the voice of her spirit control was heard. He identified himself as Albert Stuart, a deceased pattern maker of Dundee who had emigrated to Australia. There is no evidence that the voice was independent of the medium’s larynx, as was reported to be the case with some other ‘direct voice’ mediums.3West (1946), 34. However, the voice was also said to lack Helen’s strong Scottish accent.4West (1946), 50. Albert acted as master of ceremonies; sitters were not allowed to move or to touch the ‘ectoplasmic’ manifestations without his permission.

The ectoplasm appeared in the form of sheets and coils of white material, which appeared to issue from Duncan’s mouth or nostrils and was found draped around her when the cabinet curtains were opened. Sometimes she walked out with it trailing behind her. Sensationally, it typically resolved into human forms who were identified as relatives of people present and even conversed with them.5For verbatim notes of a sitting, see Gaunt (2015), 248-55. The undervest claimed to have been used to represent ‘Peggy’ is pictured on p. 231.

First Investigations

Duncan’s mediumship was mired in conflicting testimonies and evidence. Psychical researchers mostly concurred that the phenomena were partly or entirely specious, but differed over the methods used.

An account of sittings written by Major CH Mowbray for the British College of Psychic Science concluded that they were fraudulent.6West (1946), 33.

The first recorded systematic investigation was conducted by the Research Committee of the London Spiritual Alliance (LSA) over the course of about fifty sittings from October 1930 to June 1931, with the participation of several investigators. Duncan was sewn into a suit with a pattern that would expose any tampering, with sewn-on gloves and foot covers, her hands and feet taped to the chair.

Five specimens of ‘ectoplasm’ were provided for examination, including one cut off as it protruded out of the medium’s mouth. Two were found to be materials such as paper and cloth mixed with an organic substance similar to white of egg. Another two were pads of surgical gauze soaked in resinous fluid, identical with a sanitary towel used by her.7West (1946), 35.

It was far from certain how Duncan produced the fake ectoplasm having been thoroughly searched, including body cavities. The committee considered regurgitation after seeing her extrude a length of white substance from her mouth, then draw it back with swallowing motions. They had her swallow a pill that would stain the contents of her stomach; this was the only sitting at which she produced no ectoplasm.

Two interim reports in Light828 February and 10 May 1931. were favourable.9These are reproduced in Gaunt (2015), 240-47. The LSA’s final report concluded that there was a mix of the genuine and fraudulent but could not agree on the proportion of each.

Harry Price

In 1931, sceptic-leaning researcher Harry Price contracted Duncan for five sittings at the National Laboratory of Psychical Research in London, which he had founded in 1925 for the purpose of scientific investigation of psychic phenomena.10Fodor (1933). He published his findings in a National Laboratory Bulletin in 193111Price (1931). and a chapter of a book he published in 1933.12Price (1933). All information in this section and the next is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted.

Price’s first test was of a sample of ‘teleplasm’ given by a friend who obtained it at a Duncan sitting. Chemical analysis showed it to be a mix of egg-white mixed with ferric chloride and other chemicals.

The first sitting took place on 4 May, and Price was permitted by Albert to feel the substance. He described it thus: ‘It was about thirty inches wide, and rather damp. It felt exactly like my summer-weight undervest. I stretched it, and the tactile impression was exactly as if I held a piece of cheese-cloth. I smelt it, and even the odour was reminiscent of a bit of ripe gorgonzola’.13Price (1933), 203.

For the four subsequent sittings, controls were stiffened: the medium was subjected to a body-cavity search and required to wear a one-piece garment, and the phenomena were photographed (see side panel). The photos revealed that the substance had characteristics of ordinary cloth. Price wrote: ‘Every length of it that was spread in front of our cameras was of about the same size. Every length shows the selvedge, warp and weft, rents in the material where it had been worn by constant use, and frayed edges. One piece reveals dirt marks where the medium trod upon it.’14Price (1933), 204.

The camera also revealed

a hand we had seen at one of the séances was a rubber surgical or household glove at the end of a cheese-cloth support. At another sitting we saw a child’s head which, ‘Albert’ informed us, was the spirit ‘Peggy.’ Our cameras revealed the fact that this particular ‘Peggy’ was merely a picture of a girl’s head cut from a magazine cover and stuck on the cheese-cloth. We also secured pictures of safety-pins which had been used in forming the cheese-cloth into various shapes.15Price (1933), 204.

Unable to find any trace of cloth in any other orifices, Price and the other distinguished researchers (who included the psychologist William McDougall) formed the opinion that Duncan must be regurgitating the material then re-swallowing it. For the fourth sitting, they attempted to x-ray Duncan in order to detect any object such as a safety pin that she might have swallowed, however, she fled, struck her husband and ran out into the street screaming and tearing her sitting garment. Having been pacified, she now consented to be x-rayed, but by this time she had had the opportunity to pass any material to her husband, who refused to be searched.

At the final sitting, permission was granted to cut a piece of the substance, which felt like sodden paper. A paper analyst described it as cheap, thin paper soaked in egg white. Microscopic analysis showed marks from pulping machines.

Price also reported that he had been approached the following year, 1932, by Mary McGinlay, whom the Duncans had employed as a maid. She claimed that one of her tasks was to purchase butter muslin, and also to wash it, as it was given to her stained, slimy and smelling rotten.

First Conviction

A sitting with Duncan was held by Scottish socialite Esson Maule in Edinburgh on 6 January 1933. Duncan’s child ‘spirit control’, a child who called herself Peggy, was seized by the hostess while a bright flashlight was switched on; several sitters signed affidavits stating that ‘Peggy’ was a woman’s undervest. Duncan was charged for fraudulent mediumship, convicted and sentenced to either a fine of £10 or one month in prison.16For details on the Maule sitting, see Gaunt (2015).

Witchcraft Trial

Having been discredited by Price, Duncan avoided investigations17West (1946-1949), 171. and over the next ten years became the UK’s best known materializing medium. Sitters enthusiastically reported phenomena that could not be explained by the regurgitation theory, including levitations, the appearance of deceased relatives who sometimes gave veridical information (the communication of intimate facts known only to the sitter), and light effects.

Sittings in January 1944 were the subject of fraud allegations that led to a high profile trial the following March. On 14 January, naval officers Lieutenant Worth and Surgeon-Lieutenant Fowler attended a sitting in Portsmouth, hosted by a Spiritualist couple named Homer.18Roberts (1945). All information in this section is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted. They became suspicious when Albert declared that Worth’s sister was appearing, as she was still living, and they noted a sound like rustling sound whenever ‘spirits’ disappeared. Worth contacted the local police, and at a second sitting was accompanied by a plainclothes policeman, who said he grabbed at the ‘spirit’, found Duncan standing on her chair, and saw her trying to hide some white fabric. Duncan and the Homers were arrested, as was a supporter named Mrs Brown.

Such cases were usually treated as fraudulent fortune-telling and the like under the Vagrancy Act of 1824; however, seeking a more severe sentence the authorities prosecuted Duncan under the seldom-used 1735 Witchcraft Act, possibly because they regarded her as a security risk. During sentencing, the judge noted that in 1941 she had been reported to police for revealing in a sitting the sinking of a British warship, months before this incident was officially disclosed.

The trial took place in a spectator-packed courtroom at Old Bailey in March and lasted eight days. Three sittings were described minutely by witnesses for the prosecution, including Worth and Fowler, and for the defence, mostly spiritualists. The jury found all four defendants guilty. The Homers were released, while Duncan was sentenced to nine months imprisonment and Mrs Brown to four.

The trial was condemned by the Law Societies of both Scotland and England as farcical and wasteful in invoking an archaic law. Prime minister Winston Churchill called it ‘obsolete tomfoolery, to the detriment of necessary work in the Courts’.19Cited in Mantel (2001). The Witchcraft Act was repealed in 1951.20See Queen’s Printer (1951).

Donald West

Shortly after the Old Bailey trial, British psychologist Donald West published a commentary on the three-hundred page report. In it he argues that scepticism is justified, and that it is more likely that the phenomena were entirely rather than only partly fraudulent. On the other hand, he adds,

If Mrs Duncan is never genuine, one has to go to fantastic lengths to account for all that has been observed by investigators. Her powers of swallowing and regurgitation must be nothing short of miraculous, and her powers of manipulation in the dark must be almost as extraordinary, including sewing in the dark and breaking out of seals and tapes without leaving any trace of damage.21West (1946), 8.

His favoured view, based on early research by the Society for Psychical Research, is that both sitters and investigators failed to observe and record correctly.22West (1946), 49.

It is difficult to reconcile this obvious skill in the art of deception with some of the very crude methods of fraud sometimes used. One finds it impossible to understand why she should have foisted specimens of fake ectoplasm upon investigators who were sure to expose it, while at the same time she was producing absolutely baffling phenomena, which, if fraudulent, must have required infinitely more subtle methods of deception.23West (1946), 49-50.

Further complications are Duncan’s obesity, which made her movements slow and ungainly, and the fact that her strong Scottish accent was not shared by her control, ‘Albert’.

West notes that the main conundrum was how the white material got into the cabinet when both medium and cabinet were searched thoroughly.

The sceptic’s answer to the Duncan ectoplasm is that the stuff consists of fine-mesh material, that is cheese-cloth or butter-muslin, which is capable of being compressed into comparatively small volume. The tulle is swallowed by the medium prior to a séance, regurgitated under cover of the cabinet curtains when ectoplasm is required, and swallowed again at the end of the sitting.

This explanation sounds so fantastic that unless there had been some very good supporting evidence it need hardly have been taken into consideration. Anyone who has had experience of the time and effort required to swallow a narrow rubber tube for the purpose of a stomach examination must marvel at Mrs Duncan and her yards of cheese-cloth. Although choking noises have been reported at Duncan seances, often enough the regurgitation must have been accomplished swiftly and silently.24West (1946), 34-5.

West considers the possibility that the medium could have evaded the search and produced the cheese-cloth without regurgitation. But she could never be sure that a vaginal and rectal examination might not be requested, and the methods of search used by Price appeared to preclude this.

An alternative explanation is that Duncan’s husband, who was almost always present, passed the cheese-cloth to her during the course of the séance. But since the light was good and Duncan could clearly be seen at the back of the room, this explanation also seems to be ruled out. West writes, ‘Whatever method of fraud Mrs Duncan used, if fraud it was, was absolutely dependable, for hardly a sitting went by without some ‘cheese-cloth’ appearing.’25West (1946), 35.

With regard to the theory that a secondary personality was responsible for Duncan’s mediumistic operations, West comments:

The difficulty with this explanation is that Mrs Duncan would have to prepare her frauds, go out and buy cheese-cloth, etc., before the sitting, while she is presumably her normal self and not under the control of any secondary personality. A more likely explanation would seem to be that her personality is subject to some degree of dissociation at all times, but that at her séances it is so extreme that her whole character may change from that of an ordinary, dull, rather clumsy woman, to a very deft and resourceful cheat.26West (1946), 51.

West draws attention to considerable inconsistencies in the witness testimony. The defence witnesses described incidents of individuals who appeared, with their speech and actions, which her accuser, Lieutenant Worth, either described differently or could not remember. For example:

Mrs Barnes gave an account of a second materialisation, this time of her granddaughter, Shirley. This was a little girl, some three feet high, who came out to the extreme left of the curtains. She stood a foot away and, taking hold of Mrs Barnes’ hand, recited, ‘This little piggy …’ in a baby voice.

All the defence witnesses were agreed on these points. Homer said he saw the child clearly. She was about three feet high and took hold of Mrs Barnes’ fingers as she recited, ‘This little piggy went to market …’ Mrs Cole said the same. Mrs Sullivan had noticed the baby fingers. Mrs Tremlett said the child was about three years of age. In defiance of all these witnesses, Worth swore he remembered no such incident.27West (1946), 58-9. Note: page numbers in the original report are given.

In another incident, Worth described a bulky form that falsely claimed to be his aunt (he had no deceased aunt), and then disappeared behind the curtain. Against this, six other witnesses described an elderly woman, giving details of her appearance and remarks that she made. These descriptions were more or less consistent with each other, including details not mentioned by Worth, for instance that she came out and peered into Worth’s face and that she vanished into the floor without returning to the cabinet.28West (1946), 54-5.

West contends that Worth was an unsatisfactory witness, having admitted to deliberately deceiving the spiritualists at the séance and telling lies. But even if his testimony is accepted without dispute, there was nothing to prove fraud from the point of view of psychical research, he adds. The prosecution’s case, based on Worth’s testimony, was that Duncan faked the materializations by wrapping herself in a sheet, which he claimed to have seen and touched when he pounced on her. But the alleged sheet was not found and no systematic search of the sitters were made. West also points out that much of the defence evidence was utterly at variance with the sheet hypothesis.29West (1946), 61.

At one point, West records, it was suggested that Duncan hold a test séance in court so that the jury could see the materializations for themselves. The judge at first declined to trouble the jury ‘with matters of that sort’, but then relented; however, the jury rejected the idea.

West concludes that the Duncan case is ‘a mass of irreconcilable contradictions.

An apparently sane and reliable witness comes along with a tale of miracles that makes the mind boggle, and the next moment another witness is giving evidence of crude and common fraud. No impartial judge would pretend to know who or what to believe … For this reason, Mrs Duncan, like all other physical mediums of any note, is an inscrutable enigma.30West (1946), 51.

Death

After her imprisonment Duncan said she would never again conduct a sitting, but soon ‘felt that strong call from the Spirit World’31Hahn (n.d.b). and began again.

Accounts of her death differ. According to Duncan’s supporters, police raided a sitting in Nottingham in November 1956 and seized her, committing what spiritualists considered a travesty: touching a medium in trance. She was not arrested, but a doctor reportedly found two second-degree burns on her stomach, which her supporters attributed to the act, and five weeks later she was dead, aged 59.32Hahn (n.d.-b). However, it has been noted that she suffered long-term health problems and had exhibited signs of heart problems as early as 1944.33Edmunds (1966), 137-44.

Legacy

A number of spiritualists said Duncan made contacts through mediums following her death. In the 1990s, the Scole Circle claimed that a copy of the 1 April 1944 issue of the Daily Mail in which her conviction was reported, apparently brand new, materialized as an apport.34Willin (2015), ‘Apports’ section.

Appeals for a posthumous pardon by Duncan’s descendants and supporters were voted down by the Scottish parliament in 2001, 2008 and 2012.35Knapton (2016).

In 2009, the rock group Seventh Son included in their album Spirit World a song about Helen Duncan, ‘The Last Witch in England’. It can be heard on YouTube here.

KM Wehrstein & Robert McLuhan

Literature

Edmunds, S. (1966). Spiritualism: A Critical Survey. London: Aquarian Press.

Fodor, N. (1933). National Laboratory of Psychical Research. In Encyclopedia of Psychic Science. London: Arthurs Press.

Gaunt, P.J. (2015). Helen Duncan, Esson Maule and Harry Price. PsyPioneer Electronic Journal 10/11, 225-39.

Hahn, M. (n.d.-a). About Helen Duncan. [Web page on official Helen Duncan site.]

Hahn, M. (n.d.-b). Helens passing (sic). [Web page on official Helen Duncan site.]

Knapton, S. (2016). Calls grow for formal pardon for ‘Britain’s last witch’. The Telegraph (3 November).

Mantel, H. (2001). Unhappy medium (I). Review of Hellish Nell: Last of Britain’s Witches by M. Gaskill. The Guardian (3 May).

Price, H. (1931). Regurgitation and the Duncan mediumship. Bulletin I of the National Laboratory of Psychical Research, London. [Web page reproduction including plates.]

Price, H. (1933). The Cheese-Cloth Worshippers. [Web page with reproduction in full.] In Leaves from a Psychist’s Case-Book, 200-210. London: Victor Gollancz.

Queen’s Printer (1951). Fraudulent Mediums Act, Ch. 33.

Roberts, C.E.B. (1945). The Trial of Mrs. Duncan. London: Jarrolds. [Internet Archive reproduction.]

West, D. (1946). The Trial of Mrs. Helen Duncan. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 48/172, 32-64.

Willin, M. (2015). The Scole Circle. Psi Encyclopedia. [Web page.]