As a boy in Lebanon, Nazih Al-Danaf recalled the life of an armed bodyguard who died by assassination. The case was investigated by Erlendur Haraldsson, professor of psychology at the University of Iceland, and is notable for the large volume of detail later verified as accurate. The bodyguard’s widow and children became convinced that Nazih was their husband and father reborn.

Contents

The Druzes

Followers of the Druze religion are centered in Lebanon but also live in Syria, Jordan and Israel. Most authorities consider the religion a sect of Islam, dating back to the eleventh century, although some consider it an independent religion. Druzes follow different scriptures than mainstream Islam and do not observe its five central tenets. About ten percent of Druzes undergo religious training and are initiated into the religion’s secretly-kept scriptures, usually at an advanced age; they then dedicate themselves to a life of abstinence and virtue, and take on the title ‘Sheikh’ for men or ‘Sheika’ for women. Druze scripture draws from the Greek philosopher Plato, who wrote of reincarnation as a genuine phenomenon in the Republic and other works.

Reincarnation is a tenet of the Druze religion and children’s past-life memories are given more credence than in many other places, making the Druzes a rich source of reincarnation cases.

Fuad Assad Khaddage

Fuad Assad Khaddage was born in 1925 in Kfarmatta, Lebanon. He had two brothers, Ibrahim and Adeeb. After graduating from school, he worked at an orphanage, then began a thirty-year career at the Druze Centre (Dar El Taifeh) in Beirut. He served both as the centre’s manager and as one of three companions/bodyguards of the spiritual leader of the Druze community in the city. He was well-liked, and those who knew him recalled him being qabadai, a courageous, strong and honest person. He and his first wife Fida had eight children before divorcing. He fathered another five children by his second wife, Najdiyah.

On 22 July 1982 three men broke into the centre and shot Fuad to death along with two gate-guards. The attackers fled and were never identified. An autopsy report showed that Fuad had been shot twice at point-blank range, one bullet striking his head and the other striking the main artery in his neck, killing him instantly.

Nazih Al-Danaf

Nazih Al-Danaf was born on 29 February 1992. He was living with his family in Baalchmay, Lebanon, when researcher Erlendur Haraldsson and his Arabic interpreter and collaborator, Madj Abu-Izzeddin, first approached them, having heard about Nazih from another family. Now eight years old, Nazih was no longer speaking spontaneously of his previous life – as is typical of children past the age of five – and only did so when asked. By this time he could only recall portions of what he had recounted when younger. However, he still remembered his violent death and spoke of having been qabadai.

Statements by Nazih

According to Nazih’s mother, Naaim Al-Danaf, he was only eighteen months old when he began speaking in an unexpected way for such a young child. He would make statements such as, ‘I am not small, I am big. I carry two pistols. I carry four hand-grenades. I am qabadai. Don’t be scared by the hand-grenades. I know how to handle them. I have a lot of weapons. My children are young and I want to go and see them’.

Nazih also expressed a wish to go to his previous home to get papers regarding money he was owed.He told his mother, ‘My wife is prettier than you. Her eyes and mouth are more beautiful’. He also said this to most of his sisters, who are all older than he is.

Nazih’s mother recalled him saying he had lots of weapons and that he wanted to bring his father to his house and show them to him. He talked about ‘my friend the mute’ who could use a gun with one hand, having lost use of the other.

About his death, Nazih recounted: ‘Armed people came and shot at us. I also shot at them and killed one. We were shot and later taken by an ambulance’. He said he remembered being given anesthesia in the ambulance, and would point to a spot on his upper arm and say: ‘This is where they stuck the needle’.

Each of these statements was corroborated by varying numbers of the other nine family members– at least one and sometimes all nine. Nazih’s sister Sabrine said she heard him say that his previous name was Fuad.

Visit to Qaberchamoun

Nazih’s father, Sabir Al-Danaf, recalled him saying that his house was in Qaberchamoun, a small town about eleven miles away from his present home. Sabir had visited the town before but knew no one there.Nazih insisted on travelling there, sometimes even threatening, ‘If you don’t take me there I am going to walk there’.

When Nazih was six, his parents finally relented. On the way they drove past a road which Nazih said led to a cave. Qaberchamoun is at the convergence of six main roads: When they reached the intersection, Sabir asked Nazih which way to go. The boy indicated one road and told his father to drive along it until they came to another road that forked and went upward. Arriving at the road Nazih had described, they turned onto it but had to stop as it was steep and slippery due to water on its surface, as a young man was washing his car above. Nazih ran off in search of the house he had previously lived in, Sabir following.

Nazih’s mother Naaim and his siblings waited by the car, and in the meantime they made enquiries of the man washing his car. He was Kamal Khaddage, son of Fuad Assad Khaddage. He described the meeting to Haraldsson later. ‘They asked if I knew someone who had been shot, they did not know his name but he had carried handguns, hand grenades, and had owned a red car’ . Surprised that the description fit his father, Kamal called his mother, Najdiyah. Nazih and Sabir then joined the group.

Najdiyah recounted: ‘When Nazih came here I was picking olives in our garden some distance away. My children yelled at me that there was a boy who said that he was their father, and they wanted me to come and see if he would recognize me. I went to them and told his mother that my husband died in the war. When he [Nazih] saw me, he looked like he knew me, and looked up and down at me. Kamal then said to him, “Is she your previous wife or not?” Nazih smiled’.

Wanting to test whether the boy really was her deceased husband reincarnated, Najdiyah asked Nazih who had built the foundation of the entrance gate. Nazih answered, correctly, ‘a man from the Faraj family’. Inside the house, Nazih went into a room with a cupboard, indicating that he had kept his pistols and other weapons in it. This too was correct, including the spot in the cupboard where the arms had been placed.

Testing him further, Najdiyah asked him if she had had an accident when they had lived in another village. He answered that while picking pine cones for her children to play with, she had slipped on plastic nylon, dislocating her shoulder. This had happened in the morning, when Fuad’s father Assad had been present. After returning from work, Fuad had taken her to the doctor, who had put a cast on her shoulder. All these details were correct. Najdiyah asked Nazih how their young daughter had been made severely ill; he answered, correctly, ‘She was poisoned by my medication and I took her to the hospital’.

Najdiyah also reported that Nazih had asked her whether she remembered certain incidents, such as the family being helped on their way to Beirut by Israeli soldiers who charged their car battery, and the night she locked Fuad out of the house because he was drunk, forcing him to sleep on a rocking sofa. He asked to see the barrel in the garden he had used to teach her to shoot, again remembering accurately.

By the end of the visit, the boy’s extensive knowledge of Fuad’s life had convinced Najdiyah and the five children that Nazih was the reincarnation of Fuad.

Recognitions by Nazih

Najdiyah reported that she showed Nazih a photograph of Fuad, asking who it was. He answered, ‘This is me, I was big but now I am small’.

Nazih and his current-life family then visited Fuad’s younger brother Adeeb, now called Sheikh Adeeb since he had been initiated into the Druze religion, at his house in Kfarmatta. Sheikh Adeeb recounted: ‘I saw a boy running towards me who said, “Here comes my brother Adeeb”, and he hugged me. I remember it was wintertime and Nazih said, “How do you go out like this, put something on your ears”. Then he told me, “I am your brother Fuad’’ ‘. Asked for proof, Nazih said he had given Adeeb a handgun as a gift, correctly identifiying it as a Checki 16, a model that is uncommon and considered precious in Lebanon.

Nazih then correctly identified Fuad’s father’s house and Fuad’s own first house,stating that the wooden ladder in it had been made by Fuad. His first wife, Fida, still lived there, and Nazih correctly identified her as ‘Im Nazih’ (‘mother of Nazih’) since her first-born son by Fuad was also named Nazih. Shown a photograph of Fuad with his two brothers, he correctly identified all three men, as well as their father in another photo. Later Sheikh Adeeb visited Nazih back in Baalchmay, bringing a handgun and asking if it was the one Fuad had given him. Nazih correctly answered no.

Sheikh Adeeb recalled that the reunion was quite emotional, with many hugs and tears.

Behavioural Signs

Nazih’s family noticed that he was unusually fearless for a young child. He displayed other behaviours reminiscent of Fuad: When he saw a cigarette box, he would sometimes want to take a cigarette out and smoke it; he also wanted whisky if he saw someone else drinking it. These behaviours were particularly marked at the same time he most frequently spoke about the past life, before the visit to Qaberchamoun.

Case Investigation

Haraldsson made six journeys to Lebanon between August 1988 and March 2001 in order to conduct a psychological study of children who remember past lives. Out of nineteen boys and eleven girls in the Druze community, he chose several for detailed investigations, including Nazih. In his case report,[Haraldsson & Abu-Izzeddin (2002). See also Haraldsson & Matlock (2016).[/fn] Haraldsson wrote, ‘The exceptional features of this case (e.g., the number of witnesses to his statements before an attempt was made to find a deceased person) seemed in particular to deserve a thorough investigation’. Haraldsson first met Nazih in May 2000, when he was eight years old.

In his investigation, Haraldsson used methodology developed by Ian Stevenson. During three trips to Lebanon in 2000 and 2001, he and Abu-Izzeddin interviewed Nazih’s mother and father, six sisters and one brother. Each was interviewed alone where possible, and asked only to report what they had witnessed personally, not what others had said they had witnessed.Each person was interviewed multiple times, months apart.

The next step was to determine how much the case had already been verified prior to investigation, and critically examine that verification by interviewing the family and associates of the deceased person Nazih claimed to have been. On two occasions, Haraldsson and Abu-Izzeddin visited Fuad’s family and took careful notes.

The final step was to check the accuracy of each statement made by Nazih, as described by his family, by comparing it with the known facts of Fuad’s life, circumstances and character, as recalled by his family and associates. Haraldsson and Abu-Izzeddin travelled from Baalchmay to Qaberchamoun twice, in order to recreate the journey that Nazih’s family had taken him on to meet his former family.

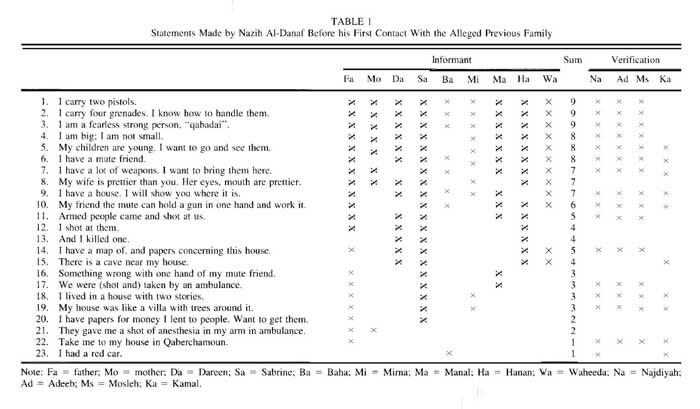

The following table showing who witnessed Nazih’s statements and who verified them is reproduced from the journal article by Haraldsson and Abu-Izzeddin.1Haraldsson & Abu-Izzeddin (2002), 368.

Analysis

Of the 23 statements that Nazih’s family recalled him saying, seventeen clearly matched the life of Fuad Assad Khaddage. With regard to the exceptions, Nazih’s memory of being given anesthetic in an ambulance does not match the autopsy report, which stated that the bullet entering Fuad’s neck had killed him quickly. It is doubtful that Fuad killed one of the attackers, as they all got away, though there were rumours of a shoot-out during the attack. The ‘mute friend’ was known to Adeeb, but not that there was anything wrong with either of his hands, and Haraldsson was not able to track down any of the man’s relatives to verify this.

Some details could not be verified. Haraldsson was unable to confirm the debts owed to Fuad, but it would have been unlikely that Fuad would have shared that information with his wife or other family members. Nazih’s avowals about the beauty of his wife are subjective, but when Haraldsson looked at a wedding photo, he too opined that she was beautiful.

Haraldsson argues that the number of statements and their specificity makes coincidence highly implausible. Together with the high number of recognitions by Nazih of former family members, he believes they provide a convincing case, even in the absence of birthmarks or other physical signs, phobias or intermission memories. He notes that the most serious weakness, a lack of written records of Nazih’s early statements, is offset by the number of witnesses who were consistent in reporting them, a feature that argues against the operation of fantasy or fraud

Haraldsson notes that in a reincarnationist culture there is a ‘certain readiness’ to accept a person’s claims to remember a previous life as true and to interpret phenomena in a reincarnationist way. But he points out it is one thing to believe in reincarnation in a general sense, quite another to accept that a young stranger truly is the deceased loved one he claims to be. Both Najdiyah and Adeeb tested Nazih’s knowledge in an appropriately sceptical way, eliciting the additional statements which convinced them he really was Fuad reborn.

Nazih’s Later Life

Haraldsson reported that after their reunion the two families continued an affectionate relationship with occasional visits. Looking back fifteen years later, he commented, ‘No case that I have investigated equals it in how perfectly the remembered statements fit the facts in the life of the previous personality.’2Haraldsson & Matlock (2016), 26.

Erlendur Haraldsson

Literature

Haraldsson, E., & Abu-Izzeddin, M. (2002). Development of certainty about the correct deceased person in a case of the reincarnation type in Lebanon: The case of Nazih Al-Danaf. Journal of Scientific Exploration 16, 363-80.

Haraldsson, E., & Matlock, J.G. (2016). I Saw a Light and Came Here: Children´s Experiences of Reincarnation. Hove, UK: White Crow Books.