José Pedro de Freitas (1918–1971), known as Zé Arigo or Arigo, was a Brazilian mediumistic healer celebrated for an apparent ability to make instant diagnoses, prescribe unusual but effective medications, and even to perform surgery without anaesthetic, while possessed by ‘spirit doctors’ in a trance state.

Contents

Background

The context of Arigo’s life and practice is a culture sympathetic to religion and the supernatural, one in which his psychic healing activity could flourish. The strong Brazilian belief in mediumship, reincarnation and after-death communication evolved from two main sources. Spiritist ideas derived from the teachings of the nineteenth century French educator and author Allan Kardec were influential among the educated classes, while religions that combined elements of Catholicism and African animism were followed by most of the population.

At the time Arigo practiced, it was not uncommon for doctors in a modern Brazilian clinic to work alongside mediumistic healers, adopting a pragmatic approach. They tended to claim consistently better outcomes than could have achieved through conventional medicine alone.

Researching his 1974 biography Arigo: Surgeon of the Rusty Knife,1Fuller (1974). All details in this article are drawn from this source unless otherwise specified. John Fuller interviewed satisfied patients of Arigo, doctors and journalists who had encountered him and witnessed his work, and other interested parties, who included a former president of Brazil Juscelino Kubitschek, British consul HV Walter, researchers Andrija Puharich and Henry Belk, and a sympathetic judge. Brazilians provided him with relevant Portuguese-language documents, including Arigo’s diaries and correspondence, court records, research notes, news stories and books about the healer.

Early Life

José Pedro de Freitas was born on his father’s farm near the village of Congonhas do Campo on 18 October 1918, one of eight brothers, and as a child was nicknamed ‘Arigo’, meaning ‘country bumpkin’. Most of his brothers went on to higher education, but Arigo dropped out after the third year and worked on the farm. He was a devout Catholic. As a schoolboy he experienced visions of a ‘bright round light’ and heard ‘a voice that spoke in a strange language’.

At the age of 25 Arigo married. He worked in an iron mine until he was fired for leading a strike against harsh working conditions, then started a restaurant and tavern.

In his early thirties, Arigo began suffering a recurring dream, sometimes accompanied by severe headaches. The dream typically took place in an operating room, where doctors and nurses worked on a patient, led by a doctor with a stout physique and bald head. The doctor spoke with a guttural German voice, and he recognized it as the one he had heard as a child.

One night, the dream became a waking vision. The doctor gave his name as Adolpho Fritz and said he had died during World War I with his work on Earth unfinished. He had chosen Arigo as the living vessel to carry on his work, aided by other deceased doctors. Arigo initial reaction was one of panic. He consulted doctors and his priest: medical examination revealed nothing wrong; the priest warned him against spiritism and attempted an exorcism.

Arigo then began to feel he should submit to the demand of ‘Dr Fritz’. He started to find himself expressing involuntary commands with healing intent. Meeting a friend who habitually walked with crutches, he yelled ‘it’s about time you got rid of them!’, snatched them away and told the friend to walk—which he did. Verbal commands to become well proved effective for other friends also. Arigo ceased to be plagued with dreams and headaches, until his priest temporarily persuaded him to stop these healing efforts, at which point they immediately returned.

Healing Career

In 1950, an incident occurred that would launch Arigo’s healing career. Arigo was involved in an election campaign on behalf of a senator, Carlos Alberto Lucio Bittencourt, who was suffering from lung cancer. The two men stayed at the same hotel. According to Bittencourt, he was unable to sleep one night when he observed Arigo enter his room holding a razor, a glazed look on his face. Arigo, now speaking in a thick German accent, said an operation must be done; Bittencourt lost consciousness. When he woke in the morning, he found his night-shirt cut and bloodstained and saw a clean, neat incision on his back. Arigo said he remembered nothing of this.

Bittencourt’s doctor carried out an examination and reported that the tumour had been removed by a surgical technique unknown in Brazil; he assumed it had been done in America. The senator, now recovered, spoke publicly about what happened, causing Arigo to become nationally famous. People began flocking to the village where he lived, Congonhas do Campo, in search of cure. Soon he was working fourteen to sixteen hours seeing three hundred to a thousand patients per day on weekdays. Bus schedules to the village were arranged around his practice hours.

Arigo declined all payment or favours for healings. To maintain this rigorous healing schedule and make a living, he sold his business and obtained a part-time junior clerking job.

Methods

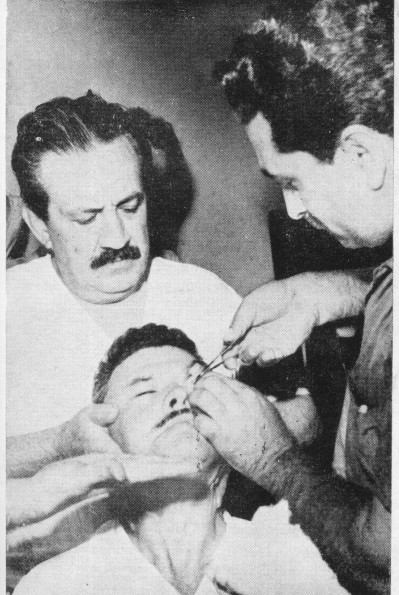

Arigo worked by entering a trance state, during which he appeared to be a different personality: he held his head higher and spoke with a German accent, his eyes seeming somewhat out of focus. He then began seeing patients.

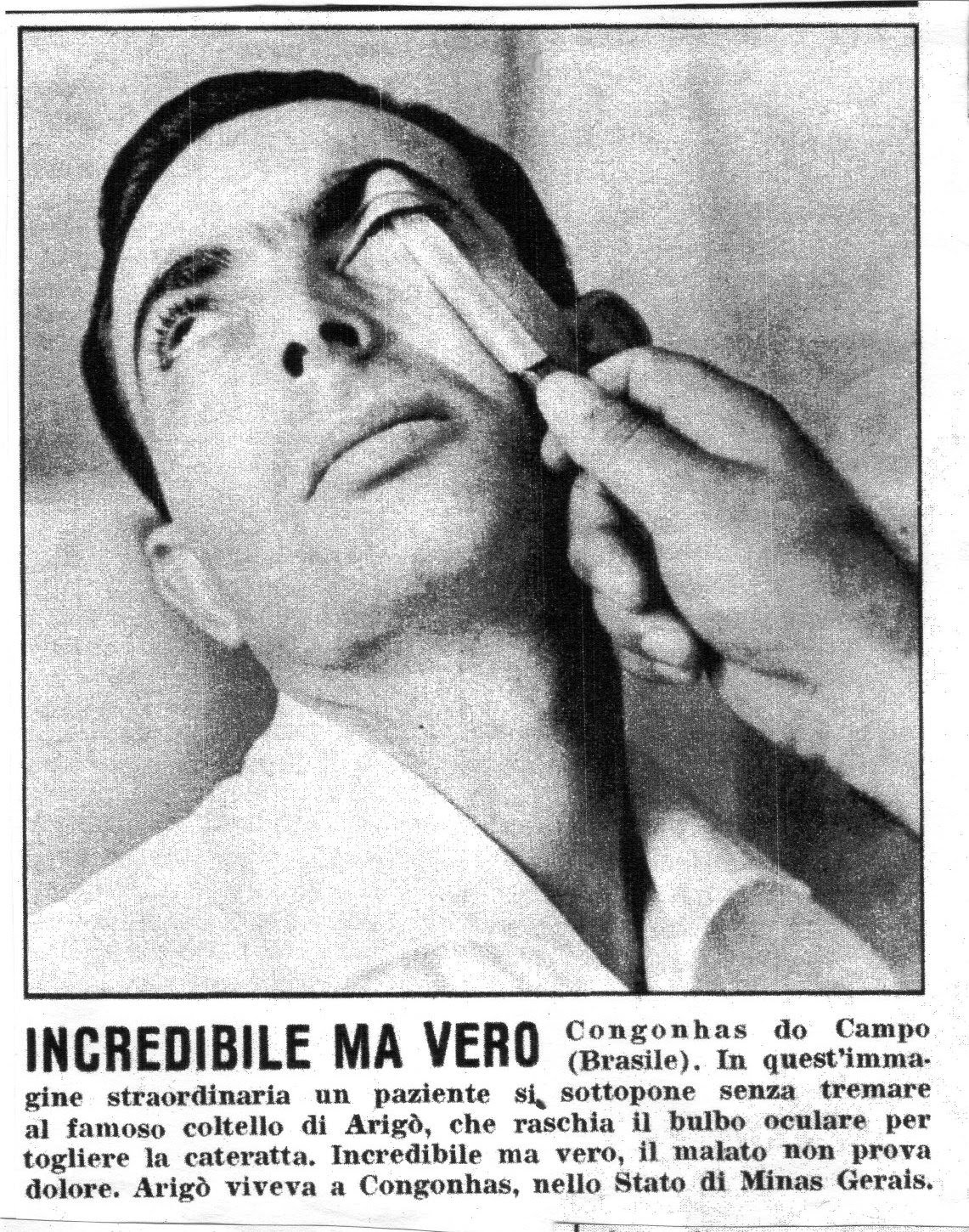

Diagnosis was instantaneous: he did not request to see records or ask questions. For some, he would write out a prescription ‘at incredible speed as if his pen were slipping across a sheet of ice’.2Fuller, (1974a), 27. The medicines he indicated might be considered obsolete or, conversely, so new they had not yet reached Brazil (many originated in Germany). With some patients Arigo carried out rudimentary surgery, plunging a paring knife into a cyst or tumour and quickly removing it. The patient could be standing against a wall, or (for major procedures) lying on a table. The operation would be performed in minutes with an unsterilized knife or scalpel and the patient would generally be able to get up, pain-free if shaken. No anesthesia, antisepsis, cauterization or stitches were used; the incisions would close of themselves. Arigo was observed numerous times stopping blood flow by a prayer.

In one instance described by Fuller:

[W]ithout a word, Arigo picked up a four-inch stainless steel paring knife with a cocobolo-wood handle, and literally plunged it into the man’s left eye, under the lid and deep up into the eye socket… Arigo began violently scraping the knife between the ocular globe and the inside of the lid, pressing up into the sinus area with uninhibited force. The man was wide awake, fully conscious, and showed no fear whatever. He did not move or flinch. A woman in the background screamed. Another fainted. Then Arigo levered the eye so that it extruded from the socket. The patient, still utterly calm, seemed bothered by only one thing: a fly that had landed on his cheek … Arigo hardly looked at his subject, and at one point turned away to address an assistant while his hand continued to scrape and plunge without letup.3Fuller (1974a), 25.

Examined by a doctor afterward, the eye showed no sign of irritation or redness.

Arigo was filmed at work on several occasions (footage by Puharich can be seen here and here). Brazilian documentarist Jorge Rizzini filmed several major operations after Arigo cured Rizzini’s wife of crippling arthritis and his daughter of leukemia.

Some patients responded well to mere commands; others he touched with his hands, as in the case of lepers. On one occasion, Arigo suddenly vomited an enormous amount of bile, then explained that the patient had been possessed by evil spirits, which Arigo had removed. The patient showed immediate improvement.

He often dismissed patients, saying a regular doctor could help them; for others he said he could do nothing. He was unable to treat himself or his relatives.

He would work until he had seen all patients who had arrived that day, even if that took until past midnight. Coming out of the trance he could remember nothing of what had happened.

Notable Patients and Observers

Fuller estimated that in total Arigo treated at least a million people. Notables whom he cured included political leaders and their relatives (for instance the daughter of president Juscelino Kubitschek who suffered from massive kidney stones), army generals, police chiefs, judges, industrialists and prominent journalists.

A baby born to the wife of Roberto Carlos, a popular singer, suffered from a type of glaucoma that specialists in Europe believed to be incurable. Arigo cured it within days, generating another round of national publicity.

The British consul to Brazil, HV Walter, observed Arigo curing liver cancer for the sister-in-law of a dentist friend. He noted that the scissors seemed to move by themselves at times, and the incision closed without stitching.

Observations by Doctors

By the mid 1950s, some Brazilian doctors were starting to take Arigo seriously. Fuller interviewed several who observed his work on patients they had declared incurable.

Dr Ladeira Margues brought a patient with inoperable ovarian cancer: following treatment by Arigo she recovered completely and eventually bore a healthy child.

A young woman with cancerous growths throughout her abdomen had been given two months to live by her physician Jose Hortencia de Madeiros. Arigo gave her three prescriptions, after which she became tumour-free and recovered completely.

Dr Ary Lex had tested mediumistic healers before, and none had passed his tests. He joined two other medical professors observing Arigo perform four operations, including the removal of a liver tumour, and concluded that more research was warranted.

Charges and Imprisonments

The Catholic Church and national and provincial medical associations were opposed to Arigo’s practice. In 1956, Arigo was charged with witchcraft, charlatanism and practicing medicine without a license, despite an absence of evidence that he had caused harm or charged for his services.

In 1957, he was sentenced to fifteen months in jail and a fine that would have bankrupted him and his wife, who had now borne six children, except that an appeal court slashed the fine and reduced the term to eight months, with a grace period of a year’s probation prior to serving the sentence. Arigo continued to help the patients who came flocking to the village, while the police turned a blind eye. In 1958 he was pardoned by Kubitschek, after which his practice returned to normal.

In 1964, at the behest of the Brazilian medical association, Arigo was again charged with witchcraft and sentenced to sixteen months imprisonment. Arigo drove himself to the jail, as no policeman could be found who was willing transport him there. Once incarcerated, he was given a key to his cell so that he could continue to treat patients covertly, sometimes being driven by the prison warden to the nearest town. Crowds seeking relief eventually turned the jail into a clinic. Arigo’s sentence was halved, then cancelled, after the region’s chief justice, at the urging of Puharich, watched him perform a cataract removal.

Investigation Attempts

Puharich and Henry Belk visited Arigo in 1963 and resolved to undertake extensive research on his abilities. Puharich asked Arigo to perform an eye exam on him with his knife: Arigo refused, considering it unnecessary; however, he was willing to remove a lipoma on Puharich’s arm that Puharich had hesitated to have removed, due to its proximity to the ulnar nerve and brachial artery. While Rizzini’s cameras rolled, Arigo asked Puharich to look away, and put the removed lipoma and the knife into Puharich’s hand within seconds without having caused Puharich any pain. (Footage of this operation is included in this video, starting at 22:40.)

Belk told Arigo about back pain that had troubled him for years, and received a prescription that, as a doctor, he found odd. However, within three weeks of his taking the medicine, the pain was gone.

Puharich and Belk resolved to attempt to verify Arigo’s cures by obtaining patients’ medical records before and after. Among 545 patients for which there were diagnostic records, it was found that Arigo’s instant diagnoses agreed with those made by the patients’ doctors in 518 cases (95%).

Preparations were made for a much more extensive course of research involving more personnel and medical equipment, and the team travelled to Congonhas do Campo in May 1968. Despite precautions, word got out, and their work was hindered by the presence of large numbers of reporters. The researchers were forced to flee when the reporters stormed Arigo’s house, following a false report that he intended to visit the US. By this time, the provincial medical association had reversed its opposition and decided that its own doctors should continue the research, analysing existing records of cures by Arigo, including two child leukemia cases where cure could be confirmed by white blood cell counts.

Commentary and Criticism

Paranormal Explanations

A spiritist group reported having received communication from Dr Fritz, and that he had revealed he had spent sixteen years preparing Arigo to act as his medium.

Another medium stated that each diagnosis was made by deceased physicians led by Dr Fritz before the patient met with Arigo. The doctors had only touched the surface of medical knowledge while they were incarnate but now, in the other world, had limitless expertise.

J Herculano Pires, a philosopher and follower of the teachings of Kardec, interviewed Arigo when he was channelling Dr Fritz in a trance state. At this time, ‘Dr Fritz’ stated that he had been born in Munich, moved to Poland at age four, lived there until he moved to Estonia in 1914, where he died in 1918. Fritz said he had become a good surgeon but made several bad mistakes, and in recompense wished now to cure as many living people as he could. Despite the details provided, attempts to verify the existence of Dr Fritz from historical records failed.

Called as a witness in a trial of Arigo, doctor Jair Leonardo Lopes speculated that the healer had the power of extrasensory perception:

He is a clairvoyant and has other exceptional faculties we can neither define nor understand. He diagnoses by clairvoyance. He “sees” the affected organs inside the patient’s body. Through telepathy, he knows what other doctors prescribe for the illness or he knows what has worked in similar cases.4Lopes (1965), Em Defesa de Arigo. Belo Horizonte. Cited in Fuller (1974a), 170.

Puharich described the sensation he felt when Arigo guided his hand putting a knife into a patient’s eye, saying it was not at all like the usual feel of a blade on flesh:

Take a pair of magnets and find the like poles of each. Then hold one magnet in each hand and bring the like poles toward each other. You will now experience repulsive forces between the two like magnetic poles … when I moved the knife into the tissues of the eyeball and the eye socket, I felt a repulsive force between the tissues and the knife. No matter how hard I pressed in, there was an equal and opposite force acting on my knife to prevent it from touching the tissues.5Fuller (1974a), 258.

Sceptics

In a critical review, sceptic Martin Gardner rejected Fuller’s account, calling it ‘despicable’. Gardner criticized the author for accepting anecdotes as facts and charged that his book would encourage some sick patients to expose themselves to quackery, perhaps dying ‘a needless death’.6Gardner (1974); see also Gardner (1981), 275-88.

In a published reply, Fuller characterized Gardner’s review as ‘calumny’ and provided detailed rebuttals. He wrote:

In combing the voluminous trial records, I found that they recorded time after time that there was no testimony that Arigo had harmed anyone is his quarter of a century practice. Furthermore, your reviewer ignores the fact that I have and quote the opinions of many doctors and scientists who observed and investigated Arigo.7Fuller (1974b).

Parapsychology detractor Joe Nickell attributed the success of Arigo’s pharmaceutical prescriptions to the placebo effect. He noted that Arigo’s healings benefited his brother, who owned the town pharmacy, implying a pecuniary motive.8Nickell (1993), 161.

Stage conjuror James Randi claimed that Arigo’s prescriptions were ‘useless’ and described the operations as ‘ordinary’. He also published a photograph of himself inserting a knife under his own eyelid without feeling pain.9Randi (1982), 174-76.

Death

Arigo had long dreamed of building a hospital in Congonhas do Campo, which would enable detailed research of his powers as well as providing patient accommodation. By late 1970, architectural designs were about to be started and plans for joint American-Brazilian research well-formed. Arigo, however, was troubled by visions of a black crucifix – a sign of impending death he had seen before, shortly before the death of Senator Bittencourt in a car accident. More than one friend heard Arigo predict he would soon die a violent death.

On 11 January 1971, aged 52, Arigo drove through heavy rain to a nearby town to buy a car. His vehicle crashed into another, having drifted into the oncoming lane. An autopsy showed that he had died of a coronary, moments before he crashed. He was buried in the Congonhas do Campo cemetery, and mourned across Brazil.

It was reported that Dr Fritz appeared to Arigo’s younger brother Eli asking him to continue Arigo’s work, but Eli, a successful law student, was not interested, and the family also was opposed.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Fuller, J.G. (1974a). Arigo: Surgeon of the Rusty Knife. New York: Thomas E. Crowell.

Fuller, J.G. (1974b). Trick or treatment. New York Review of Books (14 July)

Gardner, M. (1974). What hath Hoova wrought? New York Review of Books (16 May).

Gardner, M. (1981). Science Good, Bad and Bogus. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Nickell, J. (1993). Looking for a Miracle: Weeping Icons, Relics, Stigmata, Visions & Healing Cures. Buffalo, New York USA: Prometheus Books.

Randi, J. (1982). Flim-Flam! Psychics, ESP, Unicorns, and Other Delusions. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.