Ninel Kulagina (1926–1990) was a Russian woman whose apparent ability to move objects by psychokinesis attracted the interest of Russian and Western parapsychologists from the 1960s. Claims by sceptics that she practised deception with hidden magnets and disguised threads were dismissed by investigating scientists, and no evidence of fraud was ever produced.

Life and Career

Ninel Kulagina was born 30 July 1926 in Leningrad (now St Petersburg), where she lived her entire life. Her full legal name at birth was Ninel Sergeyevna Mikhailova. ‘Ninel’ (‘Lenin’ spelled backwards) was a popular name for girls in Leningrad at the time of her birth. In Russian media she was referred as Nelya Mikhailova; in the West she was known (erroneously) as Nina Kulagina.1

Kulagina took part in the Red Army’s defence of Leningrad during the Nazi siege along with her father, brother and sister, becoming a radio operator in a tank regiment at the age of fourteen.2 Aged seventeen she was wounded in the abdomen.

After the war she married Viktor Vasilievich Kulagin, a Russian naval engineer, and bore three children.

In the early 1960s, Kulagina was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown, possibly as a result of chronic pain from her wound or from delayed post-traumatic stress disorder. Early in December 1963, she heard a radio report about a woman who could ‘see’ colours with her fingers, and declared, ‘I can do that!’, recalling that while convalescing in hospital she had been able to pick the coloured threads she needed for her embroidery from an opaque bag without looking at them. To convince her disbelieving husband she demonstrated this ability while blindfolded: In repeated experiments she showed that as well as correctly identifying hidden colours she could read text, discern the dates on coins, and accurately reproduce simple drawings made by him in a separate room.

These experiments came to light some weeks later when the couple told a doctor about them. Two decades of investigation on her additional aptitude for psychokinesis followed, mostly conducted by Russian scientists but also, intermittently, by five Western scientists who became aware of Kulagina through a 1968 documentary film: Jürgen Keil, Benson Herbert, J Gaither Pratt, Montague Ullman, and JA Fahler. More than one hundred and possibly more than two hundred sessions were undertaken, some in laboratories.

After a long period of poor health Kulagina died of a heart attack on 11 April 1990, aged 63.

Main Sources

Several articles, including some by Russian authors translated into English, are found in the Journal of Paraphysics, a British publication edited by Benson Herbert (see Literature). A detailed article written by Jürgen Keil and colleagues, summarizing ten years of testing of Kulagina by Russian and Western scientists, is published in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research, from which much of the information in this article is taken.3

Characteristics

Typically, Kulagina sat at a small table and was observed to move small objects placed in front of her, without touching them, apparently by a process of mental concentration. The objects included such items as matchsticks, an empty box of matches, a cigarette, an empty metal salt shaker and a wristwatch. The usual starting distance between her and the objects was about half a metre but successes from up to two metres away were reported. Sometimes she succeeded with objects placed on a chair or on the floor.

Initially, the objects moved towards her; in the later phase they tended to move away. At first Kulagina moved her body or pointed her head, but later she also made hand movements, which she felt aided the process.

The movements were sometimes fairly smooth, at other times jerky. For an extended movement, several spells of short motion were performed. The movements were slow and did not achieve momentum, requiring the continued application of force to maintain, although they would sometimes continue for a short time after Kulagina stopped concentrating. She found it easiest to move a long object standing on its end: even one as light as a cigarette tended not to fall over while being moved.

Objects ranged in size from a single match to a ten-centimetre plexiglass cube (which moved while she was attempting to move items inside it). The Russian scientist GA Sergeyev reported that she moved objects as heavy as five hundred grams. She was able to move a single object among many along a predetermined course, or several at once in one direction, or two in different directions.

She was also observed to

- spin a compass needle 360 degrees in either direction

- stop a pendulum or change the direction of its swing

- move a hydrometer floating in water within a wire cage

- prevent a scale from unbalancing when extra weight was placed on one of its pans

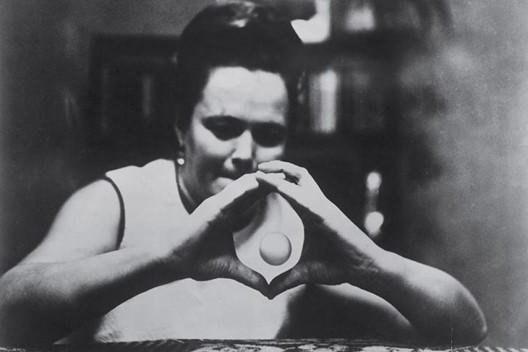

Black and white photos show her levitating a small ball between her hands, though their original source is not clear (see figure 1, below). Sergeyev stated that he observed this feat.

Figure 1: Ninel Kulagina levitating a ball. Source: Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

Kulagina was reported to have stopped the beating of a disembodied frog’s heart and to have revived fish that were near-dead, including one that was floating upside down and another lying motionless on the aquarium floor: they swam for several minutes.

Kulagina reportedly could induce the sensation of heat on a person’s skin with light contact of her hand, the intensity depending on the person. Herbert described it as unbearable pain while Keil and Fahler felt endurable heat and pain, and retained ‘burn’ marks without blistering. A thermometer placed between her hand and the observer’s showed no change in actual temperature.

Sergeyev stated that Kulagina was able to psychokinetically ‘draw’ simple patterns on photosensitive paper, but Western scientists obtained no tangible evidence of this.

Inhibiting Factors

Kulagina was able to successfully produce PK effects in some 80% of her attempts on average, Keil and his co-authors estimate. The presence of hostile observers inhibited her, but if she persisted she would eventually succeed. Screens made of various materials had no inhibiting effect. Notably, she was unable to move an object in a vacuum, although this may have been a result not of the vaccuum itself but of the object being concealed in a hermetically-sealed container, which appeared to have an inhibiting effect.

Kulagina stated that PK was difficult to achieve during hot weather and storms. Sergeyev determined that high humidity was an inhibitor also.

Physiological Changes

Kulagina’s heart rate was found to increase during her PK attempts, as high as 240 beats per minute. Ullman measured a resting heart rate of 85 and a working heart rate of 132.

Kulagina tended to lose as much as two kilograms weight during sessions – more than would typically be lost in a similar period by means of strenuous physical exercise. Adverse effects reported by her included extreme exhaustion, dizziness, pain in the neck, upper spine, legs and feet, general aches, and a metallic taste in her mouth. She sometimes required breaks of one or more days between sessions.

EEG monitoring showed marked changes during PK effects, including a concentration of energy in the direction Kulagina was gazing.

Film

Kulagina’s PK effects were often filmed, first by her her husband and then by others. Many clips can be found on YouTube, some here, showing the addition of hand movements, tests with the compass, and subjective sensations of heat. This video also shows experiments with what seems to be genuine heat used to mark plastic and cut cords, and her final test, in which she was unable to perform PK.

This video includes a short interview with Keil and film from when he and Pratt unexpectedly dropped in on Kulagina, and she invited them to stay for dinner and a PK demonstration.

Commentary

In a paper on his neuropsychiatric model of psi, psychiatrist Jan Ehrenwald observes that psi apppears to extend the typical boundary between ego and non-ego (that is, what a person considers ‘I’ as opposed to ‘not I’) and in this respect is the mirror image of physical paralysis, in which something which was ‘I’ becomes ‘not I’ for all intents and purposes.4 Ehrenwald notes that the degree of effort expended by psychics such as Kulagina in moving small objects is strongly reminiscent of a patient’s attempts to move a paralyzed limb.5

Liudmila Boldyreva notes that Kulagina’s inability to move objects in a vacuum rules out the notion that her PK involved emitting a flow of particles, which a vaccuum would not prevent. To her, this and other apparent properties suggest the psychic’s mental ‘push’ travels through a perturbed superfluid, influencing the spins of fermions (pairs of oppositely-charged particles).6

Parapsychologist Stephen Braude observes that twentieth-century reported instances of macro-PK such as Kulagina’s appear to be achieved at greater cost in terms of effort and discomfort than those of earlier feats by individuals such as DD Home. He hypothesizes that increasing general fear of psi and its implications might have caused this change. ‘If a psychic has to expend such an effort to do so little’, Braude writes, ‘then (in a careless line of thought characteristic of much self-deception) it will seem that no (or only a fatal) human PK effort could produce a phenomenon worth worrying about’.7

Accusations of Fraud

Accusations of fraud were made against Kulagina from the outset of the investigations, and these have continued to the present day. None have ever been substantiated, however.

Against Russian Scientists

According to Kulagina’s husband, the first Soviet scientist to invite her into a laboratory, LL Vasiliev of Leningrad University, was open to the possibility that her abilities were real, having previously written a book on psychokinesis. However, his junior associates believed she was ‘fooling the gullible old professor’ by using invisible threads, and the university authorities ordered him to cease experimenting.8

Similar problems plagued her and Russian scientists throughout the investigations. One scientist, Eduard Naumov, was arrested by the KGB and imprisoned for a year in a work camp, apparently because his frequent meetings with Western parapsychologists related to his work with Kulagina aroused police suspicions.9

Institute of Metrology Report

A 1968 article for Pravda assessed media claims concerning Kulagina. It cites, alongside positive testimonies, a report in a Leningrad evening newspaper, Vyecherny Leningrad, which states that in 1965 scientists at Moscow’s Research Institute of Metrology concluded unanimously that she had used ‘small magnets concealed in intimate places’, and that other experiments it performed that were set up to exclude fraud did not yield positive results. The Pravda article also states that the Leningrad Psychoneurological Institute concluded that the claims amounted to a ‘public fraud’.

The same article reveals that Kulagina served a jail sentence for ‘fraudulent intrigues’ implying a tendency towards criminal activity that could explain her psychokinesis activities as tricks.10

Western Critics

Similar claims have been made by Western critics, who assert that Kulaginia manipulated objects by means of magnets concealed in her clothing or vagina, or by deftly using disguised threads. Several authors quoted by Wikipedia state that Kulagina was caught cheating by Soviet scientists.11

These criticisms appear to be mainly based on assertions by career sceptic Martin Gardner in works criticizing parapsychology and paranormal claims. Gardner describes Kulagina as ‘a pretty, plump, dark-eyed little charlatan who took the stage name of Ninel because it is Lenin spelled backward … and is pure showbiz’. He further states that ‘Soviet establishment psychologists caught her cheating using techniques familiar to all magicians’. 12 This relates to remarks in a separate article on ‘demo-optical perception’, in which he reports an early demonstration by Kulagina of eyeless sight, as reported by the Leningrad newspaper Smena (16 January 1664) at the Psychoneurological Institute in the Lenin-Kirovsk district. In this demonstration Kulagina is said to have, while blindfolded, ‘read from a magazine and performed other sensational feats’. Gardner attributes such successes to the inability of a simple blindfold to prevent seeing, and argues that no test that does not encase the entire head in a covering is adquate.13 He further quotes from another research institute in Leningrad in which she was given tasks under two conditions, one in which lax controls would allow her to peek and the other in which peeking would be impossible. ‘Phenomenal ability’ was shown in the first condition, but none at all in the second, from which it was inferred that the claim was an ‘ordinary hoax’. 14

Gardner quotes a New York Times story of 21 May 1968 that 'Ninel, now using the pseudonymn of Nelya Mikhailova, had been caught again. She was found employing concealed magnets to fool ‘Soviet scientists and newsmen into thinking she possessed the ability to move objects by staring at them ... four years earlier, the same report revealed, Ninel had received a four-year prison sentence'.15

Counterclaims

Keil and colleagues devote a section of their detailed paper to the issue of potential fraud by Kulagina. Keil (the lead author) asserts that despite accusations ‘so far no direct evidence exists that she ever used deception during her PK demonstrations’.

With regard to the report by the Institute of Metrology upon which some criticism is based, Keil points out that it includes a statement indicating that a strong magnetic field was detected around Kulagina's body, which may have led some or all the investigators to conclude that Kulagina was concealing magnets. However, no search was made and there was therefore no direct evidence of this. Alternatively, Keil suggests, this interpretation may have been made by later critics.

Keil also points to a reference by Kolodny, who quotes from the Institute of Metrology report as follows:

The committee notes that the transference of objects took place. An aluminium pipe (diameter 20 mm and height 47 mm) was moved 90 millimetres, and a container of matches was moved over a similar distance. Aluminium pipes were moved both under a glass lid and without the lid. Observation by a section of the committee was carried out both in direct proximity and from a distance with the help of a television camera. The committee at the present time cannot give an explanation of the observed phenomena of the transference of objects.16

There is therefore no indication that the report drew sceptical conclusions, as claimed by hostile critics. Keil concludes:

It seems fairly certain that although the above-average magnetic field around Kulagina was measured, the question whether she was hiding magnets was not directly investigated by the Metrology Institute. Russian physiologists working in Leningrad, among them Sergeyev, mentioned in discussions that a relatively strong magnetic field is one of the physiological characteristics of Kulagina. It seems very likely that Sergeyev was able to rule out to his own complete satisfaction the accusation that this field was created by hidden magnets.17

Keil also notes that Kulagina moved objects made of non-magnetic materials such as ‘glass, plastic, aluminium, copper, bronze, silver, ceramic, paper, fabric, water, wood and other organic materials, including bread’. He concedes that the question of trickery by Kulagina cannot be resolved in absolute terms, but nevertheless asserts that the evidence against it is ‘quite substantial’. He points out that Russian scientists carried out a large number, possibly as many as two hundred, of observations and experiments, some of them in laboratories with sophisticated monitoring equipment. He continues:

It could be suggested in the West that because Russians had not experienced a period of fraudulent seances they may have been misled more easily. Not all the Russians' observations were carried out by scientists under laboratory conditions, but many of them were; and the few written reports which are available … suggest that the investigations were carefully controlled to insure that fraud could not explain the phenomena. The additional direct observations by visitors from the West … included a number of new controls.18

Keil adds that aspects of the film recordings of Kulagina’s activity reveal many features that make fraud ‘very unlikely’ and give no support to suggestions of fraudulent manipulation. He concludes, ‘From all the evidence now at our disposal it seems reasonable to conclude that Kulagina does not behave like a person who is trying to conceal something.’19

Details of Kulagina’s legal troubles are given by authors Shiela Ostrander and Lynn Shroeder, who state that they arose from bungled attempts to act as a broker for neighbours to help them buy scarce refrigerators and furniture, and that this resulted in a 1966 conviction when the neighbours complained. Following an intercession on her behalf by a senior scientist her prison sentence was commuted to time in hospital.20

James A Conrad gives further detailed counterarguments to sceptic claims, based on film excerpts, here.

Defamation Suit

A second police investigation some years later followed complaints that Kulagina was acting as a fraudulent psychic. This was brought up in the course of a 1986 defamation trial instigated by Kulagina against a popular monthly magazine Man and Law published by the Soviet ministry of justice.21 The publication had accused her of cheating, and this second investigation was cited by the defendant as further evidence of her bad character, but there is no sign that any charges were brought against her for this. Several Russian witnesses testified in her defence, including reputable scientists, a journalist, a documentary filmmaker and others. One was Naumov, who pointed out that Kulagina had shown no desire for publicity or profit. The jury ruled in her favour, finding that the magazine could produce no tangible evidence of fraud by Kulagina, although it stopped short of endorsing her ability, and the court ordered the magazine to publish a retraction.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Adamenko, V. G. (1972). Controlled movements of objects. Journal of Paraphysics 6, 180-226.

Boldyreva, L.B. (2007). Is long-distance psychokinesis possible in outer space? Paper presented at the 50th annual convention of the Parapsychological Association, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 2-5 August.

Braude, S.E. (1993). The fear of psi revisited, or, it’s the thought that counts. ASPR Newsletter 18/1, 8-11.

Chijov, V. (1968). Wonder in a sieve. Moskovskaya Pravda (4 June). Trans. S. Medhurst in Journal of Paraphysics 1968/2, 109-11.

Conrad, J. (2016). The Ninel Kulagina Telekinesis Case: Rebuttals to Skeptical Arguments. [Web page.]

Dash, M. (1997). Borderlands. Portsmouth, NH, USA: William Heinemann.

Ehrenwald, J. (1976). Parapsychology and the seven dragons: A neuropsychiatric model of psi phenomena. In Parapsychology: Its Relation to Physics, Biology, Psychology, and Psychiatry, ed. by G.R. Schmeidler, 245-63. Metuchen, New Jersey, USA: Scarecrow Press.

Gardner, M. (1983). Science: Good, Bad and Bogus. Oxford: OUP.

Gardner, M. (1992). On the Wild Side. Amherst, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Herbert, B. (1973). Spring in Leningrad: Kulagina revisited. Parapsychology Review 4, 5-10.

Keil, H.H.J., & Fahler, J. (1976). Nina S. Kulagina: A strong case for PK involving directly observable movements of objects. European Journal of Parapsychology 7/2, 36-44.

Keil, H.H.J., Herbert, B., Ullman, M., & Pratt, J.G. (1976). Directly observable voluntary PK effects: A survey and tentative interpretation of available findings from Nina Kulagina and other known related cases of recent date. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 56, 197-235.

Kolodny, L. (1968). When apples fall. Moskovskaya Pravda (17 March). Trans. S. Medhurst in Journal of Paraphysics 1968/2, 105-8.

Kravitz, J., & Hillabrant, W. (1977). The Future is Now: Readings in Introductory Psychology. Chicago: F. E. Peacock Publishers.

Kulagin, V. V. (1971). Nina S. Kulagina. Journal of Paraphysics 5, 54-62.

Kulagin, V. (1991). The ‘K’ phenomenon: The phenomenon of Ninel Kulagina (no page numbers). In The Phenomenon of ‘D’ and Others, ed. by L.E. Kolodny, 107-221. Moscow: Politizdat. [Trans. Google Translate and KM Wehrstein.]

Levy, J. (2002). K.I.S.S. Guide to the Unexplained. London: DK Publishing.

Ostrander, S., & Shroeder, L. (1970). Psychic Discoveries Behind the Iron Curtain. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Rejdak, Z. (1968). Telekinesis or fraud? Journal of Paraphysics 2, 68-70.

Rejdak, Z. (1969). The Kulagina cine films: Introductory notes. Journal of Paraphysics 3.

Stein, G. (1996). The Encyclopedia of the Paranormal. Amherst, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Ullman, M. (1974). PK in the Soviet Union. In Research in Parapsychology 1973, ed by R.L. Morris & J.D. Morris, 121-25. Metuchen, New Jersey, USA: Scarecrow Press.

Endnotes

- 1. Conrad (2016).

- 2. Kolodny (1968). See also Conrad (2016), from which all information in this section is drawn except where otherwise noted.

- 3. Keil, Herbert, Ullman, & Pratt (1976).

- 4. Ehrenwald (1976), 247-49.

- 5. Ehrenwald (1976), 260.

- 6. Boldyreva (2007).

- 7. Braude (1993), 10.

- 8. Kulagin (1991).

- 9. Conrad (2016).

- 10. Chijov (1968), 110.

- 11. E.g., Dash (1997), Kravitz & Hillabrant (1977), Levy (2002), Stein (1996).

- 12. Gardner (1981/1989), 244.

- 13. Gardner (1981/1989), 65-7.

- 14. Gardner (1981/1989), 70.

- 15. Gardner (1981/1989), 244.

- 16. Kolodny (1968), 107.

- 17. Keil, Herbert, Ullman, & Pratt (1976), 203-4.

- 18. Keil, Herbert, Ullman, & Pratt (1976), 204.

- 19. Keil, Herbert, Ullman, & Pratt (1976), 204.

- 20. Ostrander & Shroeder (1970).

- 21. Man and Law (Человек и Закон) 1986/9, 1987/6.