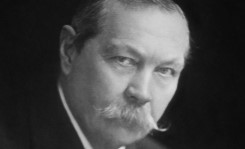

The famed novelist and creator of Sherlock Holmes (1859–1930) claimed often to have witnessed mediumistic phenomena and to have received communications from the dead. In his later years he became an evangelist for spiritualism, promoting the religion in his writings and lectures. Among the wider public his credibility suffered from an uncritical support of fraudulent claims.

Contents

Life and Career

Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born on 22 May 1859 in Edinburgh, the second of seven children. His father was an artist, his mother a descendant of an aristocratic family. Doyle entered a Jesuit college in Lancashire, then attended Stonyhurst College where he founded a school magazine. He left the school at sixteen, rejected Christianity and became agnostic.

Doyle studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh, earning his MD in 1881. He enlisted as a doctor on a ship and practised ophthalmology in Southsea, near Portsmouth. At this time he began to publish short stories and by the 1990s had achieved success with his Sherlock Holmes character, enabling him to leave medical practice for full-time writing.

Doyle supervised a hospital in South Africa during the Boer War (1899-1902), then wrote two books about it, one of which earned him a knighthood. In 1914, he formed a volunteer unit serving behind the lines. In 1916 his eldest son was seriously wounded, dying two years later. By 1918 Doyle had also lost his brother, a brigadier general, two brothers-in-law and a nephew.

Doyle produced some 240 fictional works in the genres of historical, fantasy, adventure, science fiction, mystery and others, and some 1,200 non-fictional works on such topics as legal cases, travel, memoirs, and spiritualism. His works are listed in full here (scroll down to section ‘His Works’) most with links to full texts.

In his last decade Doyle lectured on Spiritualism in Australia, New Zealand, the US, Canada, France, South Africa, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Kenya, the Netherlands and Scandinavia. In 1929, he suffered a heart attack, the first of several, and died on 7 July 1930, aged 71.1Barquin (2018).

Spiritualism

Doyle’s training as a physician imbued him thoroughly with materialistic thinking.2Wingett (2016). All information in this section is drawn from this source unless otherwise noted. The full title of the magazine is Light: A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research. However, as a young doctor he successfully experimented with telepathic drawing with a friend and became interested in Theosophy. He also attended a table turning sitting, which did not impress him, but was more convinced by an incident during a sitting, when he was warned against a particular book he had planned to read; he felt as if something had entered his memory and probed it, taking the phenomenon beyond telepathy into the active agency of a spiritual being.

Doyle began investigating psychic phenomena and hypnosis, joining the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in 1893. At this early stage he favoured rigour against fraud, urging in the spiritualist journal Light that ‘the Augean stables of professional mediumship’ be cleaned out. He further wrote, ‘The Spiritualist ought surely to be keener than any other man in holding up to odium the villains who degrade and prostitute a religion in order to put a few dishonest dollars in their own pockets’.3Doyle (1887).

At first he was put off by apparently misleading replies from ‘spirits’ during sittings, but accepted the explanation there were untrustworthy personalities in the spirit world just as in the material world.

Doyle began writing in Light again in 1916, launching a personal spiritualist mission in reaction to the carnage of the Great War. Deaths in almost every family were generating an interest in what happened after death and the possibility of communicating with the dead, he wrote. As well as the male family members fallen in war, his children’s nanny Lily Loder-Symonds and a former sister-in-law also died around the same time. He had witnessed Loder-Symonds use automatic writing to predict the sinking of the Lusitania with loss of 1,200 lives and a profound effect to follow, which he gathered meant the entry of the US in the war.

Doyle held that psychical research and spiritualism were profoundly relevant to conventional religion, a theme he pressed to the end of his life. In 1916 he wrote in Light:

There is, as it seems to me, something very surprising in the limited interest which the churches take in psychical research. It is a subject which cuts at the very root of their existence. It is the one way of demonstrating the independent action of soul, and therefore, to put it at the lowest, the possibility of its existence apart from bodily organs… Myers, Gurney and Hodgson [all deceased SPR investigators who had reportedly communicated to the living after death] are messengers of truth from the Beyond as surely as Isaiah or Amos… Personally I know no single argument which is not in favour of the extinction of our individuality at death, save only the facts of psychic research.4Doyle (1916a).

Spiritualism, Doyle wrote months later, was a new Revelation – the greatest religious event since the death of Christ. The existence of spirits had been proven, he declared; now it was time for religion to reconstruct itself around the demonstration as opposed to mere faith in immortality. He also laid out a model of life and death derived from the findings of psychical research:

Death makes no abrupt change in the process of development, nor does it make an impassable chasm between those who are on either side of it. No trait of the form and no peculiarity of the mind are changed by death, but all are continued in that spiritual body which is the counterpart of the earthly one at its best, and still contains within it that core of spirit which is the very inner essence of the man … Nor apparently are the spirit’s surroundings, experiences, feelings, and even foibles very different from those of earth. A similar nature in the being would seem to imply a similar atmosphere around the being to meet the needs of that nature, all etherialised to the same degree.5Doyle (1916b).

He asserted the nonexistence of hell, citing the claim by deceased communicators ‘that judgment is a self-acting thing by which like is brought to like, and that none are so lost that they will not work their way upwards, however much sin may have retarded their journey’.6Doyle (1916c).

On 25 October 1917, Doyle delivered a speech at the London Spiritualist Alliance in which he set out his positions, noting that they contradicted no religion or philosophy except materialism. The following March he published a book entitled The New Revelation, in which he made the same points. He began lecturing throughout England, drawing large crowds. Boosted by his support – Doyle was well-known and respected as a writer – the spiritualist movement approached the apex of its popularity. In May 1920, shortly after the debate with McCabe, Doyle announced that he and his wife would dedicate the rest of their lives to the promotion of spiritualism; their global missionary voyage began in August.

Criticism and Controversy

Christians were divided on whether revelations from spirits confirmed or contradicted scripture. Spiritualism had clergymen among its adherents, but by and large the authorities and thought leaders of the Anglican and Catholic churches, most notably the Jesuit Father Bernard Vaughan, were opposed to it, sometimes attributing it to demonic or diabolical forces. Against Vaughan’s warning that spiritualism could lead to insanity, Doyle cited an American study of 13,500 mental patients which showed that 215 were clergymen and only four were spiritualists. The Anglican Church eventually decided that spirits were real, but that spiritualism minimized the importance of Christ and therefore should not present itself as a religion.

Psychical researchers sympathetic to survival were cautious at best with regard to Doyle’s enthusiasm. William Barrett, for instance, wrote in Light that psychical research ‘may strengthen the foundations but cannot take the place of religion’.7Barrett (1916). Investigators generally regarded Doyle as credulous, his enthusiastic embrace of spiritualist beliefs profoundly antithetical to their attitude of open-minded scepticism.

Secular commentators responded to spiritualist claims mostly with mockery, supported by exposures of fraudulent mediums. Free-thinker Joseph McCabe challenged Doyle to a public debate, which was widely reported but failed to achieve a clear victory for either side.

Doyle’s reputation suffered a serious setback when he appeared to take at face value photographs produced by two young girls in Cottingley, Yorkshire – Elsie Wright, aged sixteen, and Frances Griffiths, aged nine – of themselves playing with apparentl fairies. The photographs were declared genuine by experts, but the figures looked suspiciously like typical nursery-tale fairies, with currently fashionable hairstyles (at the end of their lives Wright and Griffiths admitted they were cardboard cut-outs).8Cooper (1982). Doyle, who had used the images to illustrate an article about fairies and followed up with a book The Coming of the Fairies, received withering criticism in the press.9E.g., Bihet (2013), Introduction.

Doyle was friends with the American illusionist Harry Houdini, despite Houdini’s contempt for mediums, asserting that spiritual forces must be involved in Houdini’s mediumistic replications. This friendship perhaps muted Houdini’s criticisms of the Cottingley case. ‘There are times when I almost doubt the sincerity of some of Sir Arthur’s statements,’ Houdini wrote, ‘even though I do not doubt the sincerity of his belief’.10Houdini (1924), 161.

Doyle’s relationship with the SPR became increasingly strained. He vigorously defended William Hope, a photographer who claimed the ability to photograph spirits, against a credible report by paranormal investigator Harry Price in the Society’s journal that Hope covertly substituted Price’s plates with his own (Price had placed invisible marks on them). He eventually left the Society, complaining that it was opposed to spiritualism (his resignation letter can be read here).

Select Spiritualist Works

- The New Revelation, 1918.

- The Vital Message, 1919.

- Verbatim Report of a Public Debate on ‘The Truth of Spiritualism’ between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Joseph McCabe, 1920.

- The Wanderings of a Spiritualist, 1921.

- The Coming of the Fairies, 1922.

- The Case for Spirit Photography, 1922.

- Our American Adventure, 1924.

- The Spiritualist’s Reader, 1924.

- The History of Spiritualism (2 vols.), 1926.

- Pheneas Speaks, 1927.

- Our African Winter, 1929 .

- The Edge of the Unknown, 1930.

Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light: 1887–1920 by M. Wingett contains a complete collection of Doyle’s writings in Light.11Wingett (2016).

Video

In a short 1929 film, Doyle discusses Sherlock Holmes and his interest in Spiritualism.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Barquin, A. (2018). Biography. [Web page, published on The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia].

Barrett, W.F. (1916). Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and psychical research: Some reminiscences and reflections. Light (11 November), 365.

Bihet, F. (2013). Sprites, Spiritualists and sleuths: The intersecting ownership of transcendent proofs in the Cottingley fairy fraud. Presented at Afterlife: University of Bristol 18th Postgraduate Religion and Theology Conference, 8-9 March 2013.

Cooper, J. (1982). Cottingley: At last the truth. The Unexplained 117, 2338-40.

Coren, M. (1995). The Life of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. London: Bloombury. [Kindle version published 2018 by Endeavour Media.]

Doyle, A.C. (1887). Mr. Hodgson [Letter to the Editor]. Light (27 August), 404.

Doyle, A.C. (1916a). Where is the soul during unconsciousness? [Letter to the Editor]. Light (11 March), 83.

Doyle, A.C. (1916b). A new revelation. Light (4 November), 357.

Doyle, A.C. (1916c). Spiritualism and religion. Light (2 December), 389.

Houdini (1924). A Magician Among the Spirits. London: Harper and Brothers.

Price, H. (1922). A Case of fraud with the Crewe Circle. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 20, 272-83.

Wingett, M. (2016). Conan Doyle and the Mysterious World of Light: 1887-1920. Portsmouth, UK: Life Is Amazing.