Russell Targ is an American physicist, laser pioneer and parapsychologist who collaborated with his physicist colleague Harold Puthoff in the study of long-distance clairvoyance, for which they coined the term ‘remote viewing’. They were contracted by the Central Intelligence Agency to create the psychic intelligence-gathering programme later known as Star Gate.

Early Life

Russell Targ was born on 11 April 1934 in Chicago.1Targ (2008). All information in this article is drawn from this source except where otherwise noted. His father William Targ (anglicized from the Polish Torgownik) became a celebrated book editor, handling The Godfather by Mario Puzo and other major works.2New York Times (1999). Targ is legally blind, having been born with congenital extreme near-sightedness and prosopagnosia, a brain disorder that limits recognition of faces. Aged nine, he moved with his family to Cleveland, Ohio, USA, and two years later to New York City.

Targ was interested in stage magic, and in his early teens was introduced by classmate Robert Rosenthal, later to become a distinguished Harvard social psychologist, to ESP-testing by means of JB Rhine’s Zener test cards. This began a lifelong interest in parapsychology. By the end of high school, he was reading the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research. He writes: ‘It became totally clear to me from my reading that some people, at least, could expand their awareness and experience to what was happening far away, or even in the future’.3Targ (2008), 32.

Targ attended Queens College in New York. He received his baccalaureate in mathematics and physics in 1954, and also studied philosophy and psychology. While performing regularly as a stage magician, he discovered he was able to discern information psychically, a phenomenon he says has been noted by other professional magicians.

While working in post-graduate physics at Columbia University, Targ was introduced to Theosophy, Vedanta and Kundalini meditation, and learned about reincarnation from a lecture on the Bridey Murphy case. During this time, he began a lifelong study and practice of Buddhism.

In May 1956, Targ left university to work in plasma physics at the research laboratories of Sperry Gyroscope Co in Great Neck, New York. There he learned to design and build high-powered microwave tubes in which electron beams travelled at nearly the speed of light, and secretly adjusted one of them to use in a successful psychokinesis experiment.4See Puthoff & Targ (1974/2011), 538. He also built a copy of an apparatus used for psychokinesis by the Swedish engineer Haakon Forwald for Eileen J Garrett and the Parapsychology Foundation.

In 1958, Targ left Sperry to join the Technical Research Group on Long Island in an abortive attempt to build the first laser. Three years later he accepted an offer to work in the laser laboratory of Sylvania Electric in Palo Alto, California. After attending a lecture at Stanford University on parapsychology he co-founded a parapsychology research group with three other professors, including Charles Tart. Targ collaborated with Tart in building a four-choice ESP tester that provided immediate feedback.

In 1972, Targ aspired to start an ESP research programme at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI). At a NASA conference about Russian parapsychology research, where he spoke about experiments he had done on the ESP tester, he met informally with two top NASA officials, one of whom was concerned that the Russians were getting ahead of the USA in psi research. Targ and physicist Harold Puthoff, who worked at SRI, were offered a contract to set up a psi research programme, and SRI agreed to host it. Targ writes: ‘In my experience trying to interest people to support ESP research, I have often found that the top people in most organizations know that psi is real and are willing to admit it’.5Targ (2008), 108.

In 2018, Targ produced a documentary film called Third Eye Spies, describing the true story of two decades of Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) psychic spying at SRI.

Star Gate Remote Viewing

Targ defines remote viewing as ‘an ability we all have to a greater or lesser degree, that lets us describe and experience activities or events blocked from ordinary perception by distance or time’.6Targ (2008), 125. This means it includes a precognitive element: ‘We have learned that it is no more difficult to psychically describe a future event than to describe one that is hidden from view but has already occurred’.7Targ (2008), 125. He describes remote viewing and out-of-body experiences as ends of a continuum rather than two distinct psychic phenomena.

The Star Gate programme, originally codenamed Grill Flame, was funded from 1972 to 1995 for about $25 million. The first phase was comprised of testing, recruitment and training, during which time impressive preliminary results were shared with the Pentagon. From 1978 onward, the group engaged in operational remote viewing for clients in government organisations, which besides the CIA and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) included the Defense Intelligence Agency, Secret Service, Air Force Intelligence Agency, National Security Agency, Army Intelligence and Security Command, US Coast Guard and Drug Enforcement Agency.8McMoneagle (2002).

Psychic personnel included Joe McMoneagle, whom Targ considers today’s premier remote viewer, photographer Hella Hammid, painter Ingo Swann, and Pat Price, who had routinely used his psychic abilities in his police work, and whom Targ describes as ‘the only person I have ever known who functioned continuously day in and day out as an obvious psychic being’.9Targ (2008), 126.

Targ and Puthoff published their remote viewing findings in prestigious journals including Nature and the Proceedings of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). (See ‘Selected Articles’ below.)

In the first test of the programme, in 1973, a CIA agent sent latitude and longitude co-ordinates to the viewers and asked for a physical description of what was there. Swann and Price described it as a super-secret crypto-radar listening site in Virginia, even identifying codenames on files; the extreme accuracy of their comments triggered a CIA investigation.

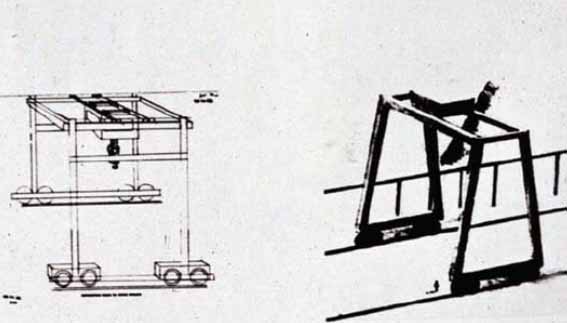

In 1974, the CIA promised to fund the project if the viewers could identify a ‘Soviet site of great interest’, for which they provided the co-ordinates. Price drew a gantry crane and other objects that closely matched information in satellite photographs.

Fig 1: Remote viewing of ‘gantry crane’. Left: Price’s drawing.Right: CIA drawing from satellite photography.10Targ (2008), 142.

Price also described the attempted assembly of steel spheres roughly sixty feet in diameter inside a building at the site; three years later this was found to be accurate, as described in an article in Aviation Week.11Robinson (1977). Cited in Targ (2008), 143. The exact diameter of the spheres was 18 metres or 57.8 feet. This success led to a Congressional investigation over whether security had been breached.

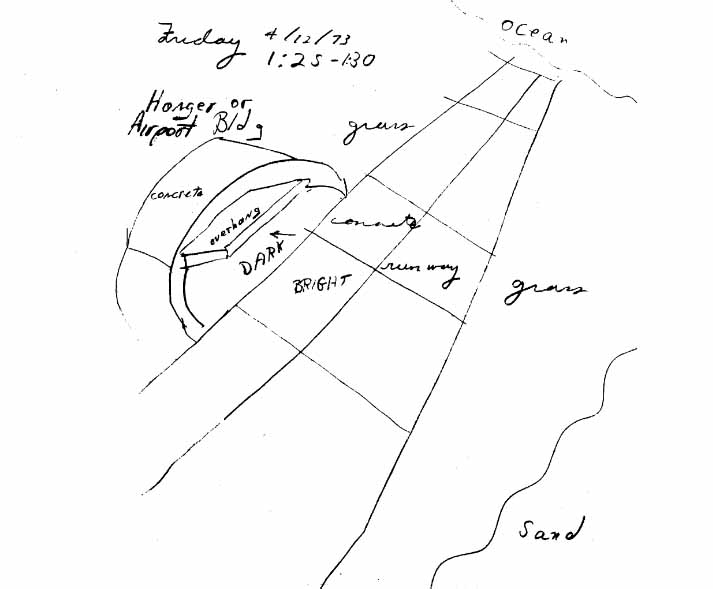

Targ experienced viewing success in his own right, standing in for Price during an experiment to psychically track Puthoff when he was away on vacation. Targ drew an impression of structures at an airport, which was confirmed to match well with an airport Puthoff had visited.

Fig. 2: Russell Targ’s drawing of an airport visited by Harold Puthoff while vacationing.12Targ & Puthoff (1974), 15.

Fig. 3: Photograph of the airport, which is on an island, as confirmed by Puthoff.13Targ (2008), 149.

Also in 1974, Price aided the attempt to find and rescue kidnap victim Patricia Hearst, identifying the kidnapping gang leader from a group of forty mugshots, and the location of the kidnappers’ abandoned car. Swann, asked what would occur three days in the future at a site in China, correctly indicated an explosion – a failed atomic bomb test. Viewer Gary Langford pinpointed a downed Soviet aircraft in Africa, enabling its capture. McMoneagle correctly discerned that the Soviets were building a seemingly implausibly huge submarine in 1979, a year prior to this being confirmed by satellite photography. During the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979-81, a Star Gate viewer correctly diagnosed one American hostage as ill shortly before his release. In 1981, McMoneagle pinpointed accurately the building in Padua where a kidnapped American general was being held by Italian terrorists, and the condition he was in, though the information was not used by Italian police.

Despite these and other successful missions, reports claiming the project yielded no useful information were produced by the National Research Council in 1986 and American Institutes for Research in 1995, and it was closed in 1995.

Later Career

Targ left the Star Gate project in 1982, disillusioned with its increasing emphasis on classified operational work at the expense of pure ESP research. He formed Delphi Associates with psychologist and remote viewer Keith Harary and businessman Anthony White. Their first project was a successful experiment at psychically predicting the market in silver futures. All of nine forecasts were correct and the team shared their profit of $120,000 with their two investors, as reported in the Wall Street Journal.14Larson (1984). However the next year’s attempt was not successful, which Targ attributes to the partners’ motivations having become less spiritual and more greed-based. Delphi folded in 1984 after working briefly with Atari to create ESP video games.

In 1985, Targ was hired as project director and senior staff scientist at aircraft manufacturer Lockheed Martin, developing laser technology for airborne detection of wind shear and air turbulence. He retired from this position in 1998 and began co-republishing out-of-print books on metaphysics, consciousness and ESP research with Hampton Roads. He continues to teach, speak and write on remote viewing and spirituality.

Targ was awarded an Outstanding Career Award by the Parapsychological Association in 2010.15Targ (2013), 376. His pioneering work in laser and laser communications earned him two awards from NASA.16Targ (n.d.).

Books

Mind Reach: Scientists Look at Psychic Ability (1977/2005, with H. Puthoff). New York: Delacorte Press.

Mind at Large: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Symposium on the Nature of Extrasensory Perception (1979, 2002, with C. Tart & H. Puthoff). Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

The Mind Race: Understanding and Using Psychic Abilities (1984, with K. Harary). New York: Villard Books.

Miracles of Mind: Exploring Nonlocal Consciousness and Spiritual Healing (1998, with J. Katra). Novato, California, USA: New World Library.

The Heart of the Mind: How to Experience God Without Belief (1999, with J. Katra). Novato, California, USA: New World Library.

Limitless Mind: A Guide to Remote Viewing and Transformation of Consciousness (2004). Novato, California, USA: New World Library.

The End of Suffering: Fearless Living in Troubled Times (2006, with J.J. Hurtak). Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

Do You See What I See: Memoirs of a Blind Biker (2008). Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

The Reality of ESP: A Physicist’s Proof of Psychic Abilities (2012). Wheaton, Illinois, USA: Quest Books.

Selected Articles

Remote viewing of natural targets (1974, with H. Puthoff). Conference on Quantum Physics and Parapsychology, Geneva, Switzerland, 26-27 August 1974.

Information transmission under conditions of sensory shielding (1974, with H.E. Puthoff). Nature 251/5476 (November), 602-7.

A perceptual channel for information transfer over kilometer distances: Historical perspective and recent research (1976, with H Puthoff). Proceedings of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 64/3 (March), 329-54.

Standard remote-viewing protocol (Local Targets) (1978, with H. Puthoff). [Internet archive version of online publication by Central Intelligence Agency.]

What we know about remote viewing (1988, with J. Katra). In Miracles of Mind: Exploring Nonlocal Consciousness and Spiritual Healing. Novato, California, USA: New World Library.

Remote viewing in a group setting (1999, with J. Katra). [Web page.]

The scientific and spiritual implications of psychic abilities (n.d., with J. Katra). [Web page.]

The speed of thought: Investigation of a complex space-time metric to describe psychic phenomena (n.d., with E.A. Rauscher). [Web page.]

Video

The Case of ESP. BBC documentary, 1983, includes live remote viewing session with Hella Hamid.

Remote viewing interview with Paula Gloria, November 2009.

An Open Mind: Six Minutes with Russell Targ, Lizzie Rose, 2013.

Precognitive Financial Forecasting with Russell Targ. Interview with Jeffrey Mishlove on New Thinking Allowed, 2017.

Banned TED Talk by Russell Targ about psychic abilities.

Third Eye Spies. Full-length documentary on the Star Gate project, produced by Targ and filmmaker Lance Mungia.

KM Wehrstein

Literature

Larson, E. (1984). Did psychic powers give firm a killing in the silver market? Wall Street Journal (22 October). [Excerpt published online at WanttoKnow.info.]

McMoneagle, J. (2002). The Stargate Chronicles: Memoirs of a Psychic Spy. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

New York Times (1999). William Targ, ‘Godfather’ editor, dies at 92. New York Times (25 July), Section 1, 31.

Pilkington, R. (ed.) (2013). Men and Women of Parapsychology, Personal Reflections: Esprit Volume 2. San Antonio, Texas and Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Anomalist Books.

Puthoff, H., & Targ, R. (1974). Psychic research and modern physics. In Psychic Exploration: A Challenge for Science, ed. by E.D. Mitchell. New York: Putnam’s Sons. [2011 ed., New York: Cosimo Books.]

Robinson, C.A. (1977). Soviets push for beam weapon. Aviation Week (2 May).

Targ, R., & Puthoff, H. (1974). Remote viewing of natural targets. Conference on Quantum Physics and Parapsychology, Geneva, Switzerland, 26-27 August 1974.

Targ, R. (1996). Remote viewing at Stanford Research Institute in the 1970s: A memoir. Journal for Scientific Exploration 10/1, 77-88.

Targ, R. (2008). Do You See What I See: Memoirs of a Blind Biker. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Hampton Roads.

Targ, R. (2013). Russell Targ. In Men and Women of Parapsychology, Personal Reflections: Esprit Volume 2, ed. by R. Pilkington. San Antonio, Texas, and Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: Anomalist Books.

Targ, R. (n.d.). Russell Targ: Brief Bio. [Web page.]