Successful ESP dreaming experiments were carried out in a sleep laboratory at the Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, New York, between 1964 and 1978. In several instances, close matches were reported between the content of subjects’ dreams and the imagery that another person in a separate room was trying to transmit to them. Critics object that the experiments should be disregarded as they have seldom been replicated. Parapsychologists argue that exact replications are inhibited by the complexity and cost of sleep laboratory research, and that the underlying principles have been successfully exploited in the more recent ganzfeld ESP protocol.

See also Dreams and ESP and this list of summaries of dream ESP research reports.

Contents

Background

For six years from 1948, the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) maintained a committee specializing in psi in the context of psychoanalysis, in which telepathic dreams are sometimes reported. One member was Montague Ullman, a New York psychiatrist and parapsychologist.1Ullman & Krippner (1973), 36. Ullman’s interest was stimulated by his experiencing occasional dreams that he thought showed putative evidence of telepathy. He describes an instance in which he dreamed that a heavily built, middle-aged classmate of his appeared, implausibly, as a ballet dancer in an opera. Shortly after this he learned that the classmate was indeed a dancer and had just performed for the first time at the Metropolitan Opera House. Ullman also observed that occasionally his patients would report a dream with seemingly telepathic content. His reading of the work of Frederic Myers, Edmund Gurney and others in the early years of the British Society for Psychical Research had drawn his attention to the relationship between apparent instances of telepathy and altered states of consciousness.2Ullman (2003).

Ullman sought to test the phenomenon in purposeful experiments, starting in 1953 with ASPR research assistant Laura Dale. The pair recorded their dreams daily, sometimes finding telepathic correspondences that related to subsequent life events. They then experimented with a ‘dormiphone’, an apparatus designed to wake the sleeper at intervals during the night and play a recorded message in order to stimulate dreaming, with some successes. Among 501 dreams collected over about two years, some 10% appeared to be paranormal.3Ullman & Krippner (1973), 59-72.

A new approach to experimental dream research became possible in 1953 with the discovery that dreaming occurs during sleep periods characterized by rapid eye movement (REM). Monitoring for such periods by means of electroencephalography (EEG) enabled a subject’s dreaming states to be precisely tracked.4Beloff (1967), 24. Ullman sought to take advantage of this to awaken a subject throughout the night to recall dreams. In 1960, he conducted pilot studies with Eileen J Garrett, a practising medium and founder of the Parapsychology Foundation, who funded the enterprise as well as acting as a participant in experiments. Garrett scored some striking hits, as did some other participants.5Ullman (1988), 299-300.

In 1961, encouraged by the findings, Ullman terminated his private psychiatric practice and accepted a full-time hospital appointment at Maimonides Medical Center, where he was able to set up a sleep laboratory.6Ullman (2003). The Maimonides Dream Laboratory opened the following year, with the participation of Stanley Krippner as co-experimenter from 1964.7Krippner (1993), 40.

Methodology

The following describes the general procedure, although variations were adopted for different studies. (Note: in these study reports, the two experimental participants are termed ‘subject’ and ‘agent’, corresponding to what in later ganzfeld ESP studies are more usually termed ‘receiver’ and ‘sender’.)

Prior to falling asleep, the subject was connected by electrodes on the scalp and eyelids to an EEG monitor and a REM monitor. He or she was awakened at the end of each REM phase by one of the experimenters and asked to report the content of any dreams. After waking in the morning for the final time, the experimenter asked the subject for general impressions about the likely target. All these conversations were recorded and transcribed.

Meanwhile during the night, at the beginning of each dream state, a buzzer rang in a separate acoustically-shielded room, where the agent then opened a sealed envelope, extracted the art print within and attempted to telepathically influence the percipient’s dreams with the imagery it contained (the print had been randomly selected from a set of twelve postcard-size art prints, all selected for use on the basis of emotional intensity, vividness, colour and simplicity, and each sealed within an opaque envelope). The random selection process was designed to ensure that no one apart from the agent knew the identity of the target picture throughout the course of the experiment.

The full set of twelve pictures and the transcribed dream reports were sent to three outside judges, who assessed the correspondences by ranking the pictures in order of most similar to the dream reports and additionally scoring their level of confidence in this finding. If the actual target was among the six top rankings it was counted as a hit; correspondingly, if it appeared in the bottom six it was counted a miss. In most cases, but not all, the subject too was asked to perform a ranking, aided by an experimenter who did not know the identity of the target picture.8Ullman (2003).

Studies

Thirteeen formal studies were undertaken throughout the period. Three further studies were pilots that aimed to identify promising participants and test new approaches.9All information for this section is drawn from Ullman & Krippner (1973).

William Erwin, a psychoanalyst, acted as subject in two telepathy studies. Judges’ rankings rated five out of seven as hits in the first series, and all eight as hits in the second series (p > .001).

Results of separate telepathy studies with Theresa Grayeb and Robyn Posin did not reach significance.

Robert Van de Castle

One of the most successful studies was carried out with Robert Van de Castle, a psychologist who had earlier obtained significant results in his own sleep and dream research. Judges’ rankings found six hits and two misses (p > .001), while his own rankings placed all eight as hits (p > .0001).

Malcolm Bessent

Two successful precognition studies were carried out with Malcolm Bessent, a young British psychic who had demonstrated a gift in real-life precognition. Here, the target picture was only selected after he had awakened in the morning and the tape recording of his dream content had been sent for transcription. To create emotional impact, soon after waking he was subjected to a multi-media sensory experience based on imagery contained in the art print (see description below). In both studies, judges ranked seven out of eight sessions as hits (p > 0.005), a total of fourteen hits.

Alan Vaughan

A study using Alan Vaughan as one of four subjects departed from the usual protocol by changing the picture once per dream state instead of once per night. The aim was partly to keep agents engaged in the process and stop them getting bored. The results were mixed, but appeared to confirm that this aided the telepathic process.

Grateful Dead

Interested in testing whether a large number of agents would enhance dream telepathy, Krippner, Ullmann and Charles Honorton arranged a pilot session with waking agents, specifically the audience at a rock concert on the night of 15 March 1970. The target theme was ‘birds’, and slides and film of birds and words related to birds were shown to the audience while the band played the song ‘If You Want to Be a Bird’ at midnight. Five volunteer subjects within a hundred-mile radius of the concert location were asked to close their eyes at the same time and record what came to mind; two subjects, one of whom was the American singer Richie Havens, experienced thoughts and images of birds or that were related to birds.10Krippner, Honorton, & Ullman (1973), 10-11.

Thus encouraged, the scientists performed a six-night test during concerts by the rock group The Grateful Dead, each with an audience of about two thousand, many of whom, the scientists surmised, would be in altered states of consciousness at the time. This time audience members were told via slides projected behind the band that they were participating in an ESP experiment. They were asked to concentrate on projected art reproductions and mentally ‘send’ them to Malcolm Bessent, who was sleeping at the Maimonides laboratory 45 miles away. They were not told about a control subject, Maimonides employee Felicia Parise, who was in bed at home being awakened by phone every ninety minutes. Bessent’s results were statistically significant while Parise’s were not, suggesting that the audience’s awareness of him enhanced the effect. However, the involvement of multiple agents rather than a single agent did not appear significantly to strengthen the effect.11Krippner, Honorton, & Ullman (1973), 11-17.

Examples of Direct Hits

In a minority of cases, dream content was clearly linked to the target picture, being classed as a direct hit.

On one night, William Erwin’s dream content included such phrases as ‘I was in a class made up of maybe half a dozen people; it felt like a school.’ ‘There was one little girl that was trying to dance with me.’ The randomly selected target in this case was Ecole de Dance by Degas, depicting a ballet dance class of several young women.12Ullman & Krippner (1973), 78.

Fig. 1: target picture Ecole de Danse, 1873, by Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas

In another case, the subject’s dream reports contained the following:

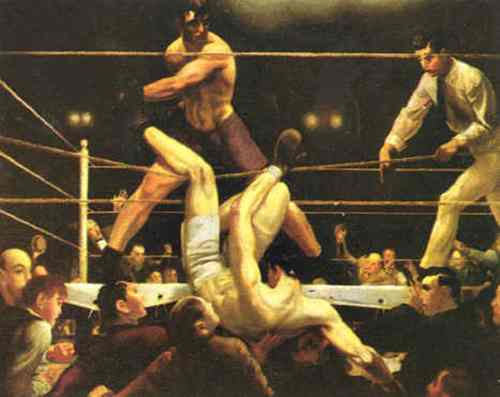

… something about posts … Just posts standing up from the ground, and nothing else … There’s some kind of a feeling of moving … Ah, something about Madison Square Garden and a boxing fight. An angular shape, as if all these things that I see were in a rectangular framework. There’s an angular shape coming down toward the right, the lower right, as if you were seeing a filming that took up a whole block … That angular right hand corner of the picture is connected with Madison Square boxing fight … I had to go to Madison Square Garden to pick up tickets to a boxing fight, and there were a lot of tough punks – people connected with the fight – around the place …13Ullman (2003), Example 7.

The target image was Dempsey and Firpo, by George Bellows, depicting a famous 1923 New York prizefight between champion heavyweight boxers. (The fight was actually staged at the city’s Polo Grounds, not at Madison Square Garden, which however is a major arena for boxing events and would have been a natural association to make.)

Fig 2: Target picture Dempsey and Firpo (1924) by George Bellows. 14All art reproductions are drawn from Ullman (2003), web version.

More examples are given here and here.

Analysis

An analysis of the Maimonides results was carried out in 1985 by Irving Child, head of the psychology department at Yale University.15Child (1985). He notes that frequent changes to the experimental protocol makes it difficult to assess the data as a whole. He also points out a potential complication in the judging procedure: a judge presented with a number of sessions to rank, finding an apparently close correspondence in one case to a particular target image, might be inclined to exclude consideration of this image from other sessions, possibly leading to error. However, he also notes that direct hits were the exception rather than the rule, tending to minimize the problem. The combined scores for three studies that were free of this problem were p < .000002.

Overall, Child notes a ‘strong tendency’ of hits to exceed misses, which he estimates as ‘significant beyond the 0.0001 level’. He comments, ‘What is clear is that the tendency toward hits rather than misses cannot reasonably be ascribed to chance. There is some systematic – that is, nonrandom – source of anomalous resemblance of dreams to targets.’16Child (1985), 1220, cited in Ullman (2003). However, he hesitates to definitely identify psychic functioning as the cause, preferring to view it as an unexplained anomaly.

A meta-analysis carried out by parapsychologist Dean Radin found the overall success rate to be 63%, significantly above the 50% mean chance expectation, of which the odds against happening by chance are 75 million to 1.17Radin (1997), 71-2.

Simon Sherwood and Chris Roe converted the test statistics for the judges rankings into an effect size measure, noting that r = 0.1 would be considered a small effect, r = 0.3 a medium effect, and r = 0.5 or above a large effect. They found effect sizes across all the data sets ranging from -.22 to 1.10. The studies with the largest effect sizes mostly involved gifted single participants who had been pre-selected (Erwin, Van de Castle, and Bessent). Very successful studies included the two precognitive studies and one pilot study, with effect sizes ranging from 0.47 to 0.73). The most successful study (r = 1.10) was the sensory bombardment telepathy study, and other studies that employed multisensory targets were also very successful.18Sherwood & Roe (2003), 88-9.

Replication Attempts

A common objection to claims of success in the Maimonides experiments is that they have never been independently replicated.19Hyman (1986).

Parapsychologists largely concur, while pointing out that few attempts have been carried out, owing to the complexity and expense of running experiments in a sleep laboratory.20Storm et al. (2017), 122; Luke (2015). Notably, experiments in which participants sleep in their own homes rather than a strictly controlled environment rely on spontaneous wakings rather than forced wakings from REM sleep, which means far fewer dreams are likely to be reported.

In a 2003 analysis Sherwood and Roe found six dream ESP studies that were carried out in other laboratories during the same period as the Maimonides experiments, and that likewise used brain monitoring and frequent wakings during REM sleep. Only one study produced significant results. The authors doubt whether these can be considered exact replication attempts because of procedural variations, inadequate reporting, precautions against security leakage, and other issues.21Sherwood & Roe (2003), 93.

Sherwood and Roe further commented on 22 formal reports of dream ESP studies carried out in the post-Maimonides period, using less expensive and less labour-intensive methods. The majority investigated clairvoyance rather than telepathy, since this does not involve a second participant to ‘send’ images. They found that, in most, the targets were identified more frequently than chance expectation, with effect sizes ranging from -0.49 to 0.80. They note that they greatest successes were achieved by certain participants and researchers.22Sherwood & Roe (2003), 93-104.

The authors estimate the combined effect size of the Maimonides studies as 0.33 and the combined effect size of the post-Maimonides studies as 0.14, concluding that, in both sets, ‘judges could correctly identify target materials more often than would be expected by chance using dream mentation’.23Sherwood & Roe (2003), 85. This review was updated in 2013.24Sherwood & Roe (2013).

A re-analysis of the Maimonides and post-Maimonides results, reported in 2017 by Lance Storm, Chris Roe and colleagues,25Storm et al.(2017). confirmed the findings of significance both in combination and separately. The authors concluded that the dream-ESP studies provide evidence that would be considered significant in mainstream psychological research.

In particular, we would now say that dream ESP is (i) a demonstrable effect; (ii) not governed by experimenter, or laboratory, or historical context; (iii) independent of (a) psi modality; (b) REM monitoring; (c) target type; and (d) agent and perceiver arrangements; and (iv) perhaps independent of the number of choices in a target set.26Storm et al. (2017), 134.

A challenge to their meta-analysis methodology27Howard (2018). was rebutted by the authors.28Storm et al. (2019).

Theoretical Conclusions

The occurrence of dream telepathy, Ullman and Krippner write, ‘leads us to conclude that the nature and fabric of the interpersonal field, and the nature of the dynamic exchanges that it encompasses, are far more subtle and complicated than current psychoanalytic and behavioural theory suggests’.29Ullman & Krippner (1973), 209.

The experimenters further state that the use of ‘potent, vivid, emotionally-impressive human interest pictures’ is important for dream telepathy experiments.30Ullman & Krippner (1973), 210. In their research, basic themes such as eating or drinking were found to lend themselves to dream telepathy, as was religion. As is the case in previous research, male subjects were found to have more dreams about sex and aggression, while female subjects tended to be more sensitive to colours and details of arrangement. For both genders, the occurrence of colour in dreams generally correlated with ESP success. Frequently, the theme of an ESP target picture triggered dreams about related events in the subject’s past.

The active involvement and engagement of the agent was found to be important, as exemplified by the success of the second Erwin study, in which agents were exposed to multi-sensory experiences. Rapport between agents and subjects also proved significant to success. Males were found to be better percipients than females, possibly due to their lower anxiety in the sleep lab setting. ESP had previously been shown to be strongly influenced by attitude and mood, as well as by a general quality of openness, and these factors were confirmed by the Maimonides research.

With respect to the purpose of dreaming itself, Ullman proposed the theory – based partly on the electroencephalographic similarity of REM sleep to regular waking consciousness – that the dream state is one of heightened vigilance and the subconscious processing of problems, sometimes leading to creative solutions. Psi is involved as a means of scanning the external environment for threats, present or future.

Ullman and Krippner’s main conclusion is that the psyche

possesses a latent ESP capacity that is most likely to be deployed … in the dreaming phase. Psi is no longer the exclusive gift of rare beings known as ‘psychic sensitives’, but is a normal part of human existence, capable of being experienced by nearly everyone under the right conditions’. A general acceptance of psi as a genuine phenomenon could allow people to realize they are ‘less alienated from each other, more capable of psychic unity and more capable of closeness in ways never before suspected … in the basic fabric of life everything and everyone is more closely linked than our discrete physical boundaries would seem to suggest.’31Ullman & Krippner (1973), 227.

Criticisms

The apparent success of the Maimonides experiments stimulated criticisms by sceptical psychologists. These in turn have been critiqued by parapsychologists including Stanley Krippner, one of the two principal experimenters.

CEM Hansel

British psychologist CEM Hansel critiqued the successful series of experiments in which Robert van de Castle acted as the main subject. Hansel attaches significance to an abortive replication attempt by Belvedere and Foulkes, in which de Castle again acted as the subject, attributing the failure to its authors having taken ‘a large number of additional and necessary precautions’.32Hansel (1989), 248. He approved the presence of Foulkes, ‘a new and critical experimenter … not strongly committed to establishing the case for ESP’,33Hansel (1989), 251. and of the presence in the report of the second study of references to checks being made throughout that the procedure was being adhered to, for instance that the seals on target envelopes had not been tampered with. In conclusion, he asserts a direct relationship between additional precautions and the failure to obtain above-chance scores.

Belvedere and Foulkes themselves did not consider that the original experiment had in fact suffered from flaws.34Hansel (1989), 248. It is not clear whether all the extra features mentioned in their study, such as continuous protocol checks, had been absent from the original study, or had merely not been reported by the experimenters. Irvin Child, then head of the psychology department at Yale University, criticized Hansel for implying that fraud was a likely explanation, given the precautions that the experimenters had employed to prevent it happening.35Child (1985).

Hansel also asserted that an experimenter was present when the agent opened the envelope containing the art print, and, knowing what it contained, was therefore in a position to transmit sensory clues about its identity.36Hansel (1980), 246, 253. This was false, as was pointed out;37Friedman & Krippner (2010), 199. nevertheless, Hansel repeated the claim in a later article.38Hansel (1985), 144.

Zusne and Jones

Psychologists Leonard Zusne and Warren H Jones critiqued the precognitive dreaming experiments carried out with Macolm Bessent as subject. They wrote that in order for dreamers to be influenced telepathically the experimenters first ‘primed’ them prior to going to sleep, ‘preparing the receiver through experiences that were related to the content of the picture to be telepathically transmitted during the night’. In these circumstances ‘it is obvious,’ they concluded, ‘that no psychic sensitivity was required to figure out the general content of the picture and to produce an appropriate report, whether any dreams were actually seen or not.’39Zusne & Jones (1982), 260-61.

As was pointed out,40Child (1985); Krippner (1993), 44. Zusne and Jones had failed to understand that this ‘priming’ activity, as they termed it, took place after the sleeping session had been completed and Bessent’s dream imagery had all been recorded. As Child stated, readers unfamiliar with the actual experiments would conclude that the researchers were completely incompetent, when ‘the simple fact, which anyone can easily verify, is that the account Zusne and Jones gave of the experiment is grossly inaccurate.’41Cited in Radin (1997), 223.

Zusne and Jones further implied that at least one of the experimenters had an opportunity to discover the identity of the target image, and that the judges knew the identity of the target while evaluating the subject’s dream content. It was pointed out that this was wrong on both counts.42Child (1985); Krippner (1993), 44.

EJ Clemner

EJ Clemner objected that transcripts of dream content might include references by the participant to previous targets, giving clues to judges about which to exclude from consideration. Krippner points out that this would only have been possible if the participants received feedback each morning, which, however, rarely happened, and in such instances the citations were deleted from the transcripts before judging.43Clemner (1986); Friedman & Krippner (2010), 198-99.

James Alcock

In addition to claims about non-replication (see above), James Alcock found fault with the absence of a control group. This complaint is rejected by parapsychologists, who point out that the control in such studies are the other non-target stimuli against which the transcript is also compared. Alcock also objected that Sherwood and Roe’s 2003 analysis was marred by ‘messiness of data’.44Alcock (2003), 29-50.

Video

Dream Telepathy with Stanley Krippner

Jeffrey Mishlove interviews Krippner on the experiments. Published on YouTube on 6 June 2016 on Mishlove’s series ‘New Thinking Allowed’.

KM Wehrstein and Robert McLuhan

Literature

Alcock, J. (2003). Give the null hypothesis a chance: Reasons to remain doubtful about the existence of psi. Journal of Consciousness Studies 10, 29-50.

Beloff, J. (1967). Report on the Maimonides Dream Laboratory. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 44, 24-27.

Belvedere, E., & Foulkes, D. (1971). Telepathy and dreams: A failure to replicate. Perceptual and Motor Skills 33, 783-89.

Child, I.L. (1985). Psychology and anomalous observation: The question of ESP in dreams. American Psychologist 40, 1219-20.

Clemner, E.J. (1986). Not so anomalous observations question ESP in dreams. American Psychologist 41, 1173-74.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Friedman, H.L., & Krippner, S. (2010). Is it time for a détente? In Debating Psychic Experience: Human Potential or Human Illusion? ed. by S. Krippner & H.L. Friedman, 195-204. Santa Barbara, California, USA: Praeger.

Hansel, C.E.M. (1980). ESP and Parapsychology: A Critical Re-evaluation. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Hansel, C.E.M. (1985). The search for a demonstration of ESP. In A Skeptic’s Handbook of Parapsychology, ed. by P. Kurtz, 97-127. Buffalo, New York, USA: Prometheus.

Hansel, C.E.M. (1989). The Search for Psychic Power: ESP and Parapsychology Revisited. Amherst, New York, USA: Prometheus Books.

Howard, M.C. (2018). A meta-reanalysis of dream-ESP studies: Comment on Storm et al. (2017). International Journal of Dream Research 11/2, 224-29.

Hyman, R. (1986). Maimonides dream-telepathy experiments. Skeptical Inquirer 11/1, 91-92.

Krippner, S. (1993). The Maimonides ESP-dream studies. Journal of Parapsychology 57 (March), 40-54.

Krippner, S., Honorton, C., & Ullman, M. (1973). An experiment in dream telepathy with ‘The Grateful Dead’. Journal of the American Society of Psychosomatic Dentistry and Medicine 20/1, 9-17.

Luke, D. (2015). Altered States of Consciousness and Psi. Psi Encyclopedia. London: The Society for Psychical Research.

Radin, D. (1997). The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena. New York: Harper Collins.

Sherwood, S.J., & Roe, C.A. (2003). A review of dream ESP studies conducted since the Maimonides dream ESP programme. Journal of Consciousness Studies 10/6-7, 85-109.

Sherwood, S.J., & Roe, C.A. (2013). An updated review of dream ESP studies conducted since the Maimonides Dream ESP Program. In Advances in Parapsychological Research 9, ed. by S. Krippner, A.J. Rock, J. Beischel, H.L. Friedman, & C.L. Fracasso, 38-81. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Storm, L., Rock, A.J., Sherwood, S.J., Tressoldi, P.E., & Roe, C.A. (2019). Response to Howard (2018): Comments on ‘A meta-reanalysis of dream-ESP studies’. International Journal of Dream Research 12/1, 151.

Storm, L., Sherwood, S.J., Roe, C.A., Tressoldi, P.E., Rock, A.J., & Di Risio, L. (2017). On the correspondence between dream content and target material under laboratory conditions: A meta-analysis of dream-ESP studies, 1966–2016. International Journal of Dream Research: Psychological Aspects of Sleep and Dreaming 10/2, 120-40.

Ullman, M. (1988). Autobiographical notes: Montague Ullman. In Lives and Letters in American Parapsychology: A Biographical History, 1850–1987, ed. by A.S. Berger, 288-304. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Ullman, M. (2003). Dream telepathy: Experimental and clinical findings. In Psychoanalysis and the Paranormal: Lands of Darkness, ed. by N. Totton, 14-46. London: Karnac Books.

Ullman, M., & Krippner, S. with Vaughan, A. (1974). Dream Telepathy: Experiments in Nocturnal ESP. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: Penguin. [First published 1973. New York: MacMillan.]

Zusne, L., & Jones, W.H. (1982). Anomalistic Psychology: A study of extraordinary phenomena of behavior and experience. Hillsdale, New Jersey, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.