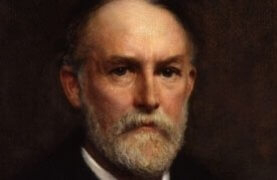

Frederic William Henry Myers (1843–1901) was one of the principal founders of the Society for Psychical Research, established in London in 1882. His book Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death, published posthumously in 1903, analyses phenomena associated with what he called the ‘Subliminal Self’, such as automatic writing, precognitive dreams and the trance states of mediums. He is regarded as a major theoretical contribution to understanding this kind of anomalous mental experience.

- Short Biography

- Early Psychical Research Activity

- Annie Marshall

- Society for Psychical Research

- Telepathy, Automatic Writing, Hypnotism

- Early Opposition

- Phantasms of the Living

- Investigations of Spirit Mediums

- Investigations of Hauntings

- Development of Myers’s Ideas

- Achievements and Tributes

- Scepticism

- Modern Re-evaluations

- Myers’s Vision

- Conviction of Survival

- Conclusion

- Select Bibliography

- Literature

- Endnotes

Short Biography

Frederic William Henry Myers was born on 6 February 1843, at Keswick in the Lake District in England. His mother was a member of the wealthy Marshall family, owners of flax mills;1 his father was the curate of St John’s, Keswick. After his father’s early death his mother moved with her sons Frederic, Ernest and Arthur to Cheltenham, where Myers distinguished himself academically at Cheltenham College, as he also did when he went up to Trinity College Cambridge, aged seventeen.

By the time Myers was 22 he had achieved two first-class degrees, in classics and moral science, as well as a glittering array of university prizes and a fellowship at his college. He was obliged to return one of the prizes, the Camden medal, following accusations of plagiarism, although it has since been argued that these were based on a misinterpretation of his motives.2

In the 1860s and 1870s Myers gained some reputation as a man of letters and poet, but held no illusions about possessing real literary talent. A seminal event was his passionate, though platonic, relationship with Annie Marshall, who was married to a cousin of his, and who committed suicide in 1876. In 1880 Myers married Eveleen Tennant, a much admired beauty and the daughter of the society hostess Gertrude Tennant.3 They had three children, and Eveleen herself became a distinguished photographer of her family and celebrity friends.

Myers possessed a strong social conscience in certain matters. He was an early campaigner for votes for women and for their higher education. He became a permanent inspector of schools in 1872, holding the post until shortly before his death.

In 1882, he joined the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) along with his close friends and fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge, the philosopher Henry Sidgwick and psychologist Edmund Gurney.

Myers was an athletic man of drive and energy: he swam beneath the falls of Niagara and across the Hellespont, for example. But he suffered from heavy colds, influenza and occasionally pneumonia through his life, and towards the end of it from Bright’s disease. While wintering abroad to gain respite and medical attention he died in Rome on 17 January 1901. His extensive work for the SPR culminated in 1903 with the posthumous publication of his masterpiece, Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death.4

Early Psychical Research Activity

Myers’s interest in psychical research was stimulated by several factors. First, from childhood he had a horror of the idea of personal extinction. Second, his childhood and adolescent religious faith could not withstand the impact of Darwinism and his own critical reading.5

Third, he was encouraged by Sidgwick’s interest in the field to probe deeper.6 He paid a heartfelt tribute at his mentor’s death in 1900:

In a starlight walk which I shall not forget ... I asked him almost trembling, whether he thought that when tradition, intuition, metaphysics had failed to resolve the riddle of the universe there was still a chance that from any actual observable phenomena – ghosts, spirits, whatsoever there might be – some valid knowledge might be drawn as to a world unseen.

Sidgwick’s cautious encouragement carried particular weight: he had been collecting accounts of ghosts for years and Myers had huge respect for his intellectual integrity.7 He also grew to admire Sidgwick’s future wife Eleanor for the clarity of her judgement and her calm approach to psychical research, a contrast to Myers’s fits of exuberance.

The death of Annie Marshall in 1876 was not the cause of Myers’s interest in psychical research, but it did give it personal resonance (see below: Annie Marshall). He threw himself into investigating mediumship and related abilities and was particularly heartened by his 1874 meeting with William Stainton Moses, a cleric and schoolmaster who possessed outstanding mediumistic gifts.8 With Myers as organizer, a circle of investigators began to develop that was based on intimate friendships, family ties and the academic and social networks of Trinity College: besides Sidgwick this included the Balfour family and in-laws, the physicist and future Noble Prize winner Lord Rayleigh, the banker Walter Leaf, and Edmund Gurney, who would become one of Myers’s most active colleagues.

At the outset the group investigated mediums from the northern city of Newcastle (Miss Wood, Miss Fairlamb and the Petty family), also a number of more fashionable mediums in London, with disappointing results in both cases. Eleanor Sidgwick reported that the ‘the indications of deception and fraud were palpable and sufficient’.9 Myers was briefly taken in by the fraudulent American medium Anna Eva Fay.10 While alive to the deceit around him, he nevertheless believed that some of the effects he had witnessed had been genuine and his commitment to the enquiry rarely wavered. He stated later that before the SPR was founded he already had three hundred and sixty seven séances recorded in his notebook.11

Though made temporarily despondent by these inconclusive results, he was encouraged by experiments in thought-transference conducted by the physicist William Barrett in Ireland. Along with Dawson Rogers, a leading Spiritualist, Barrett urged that a concerted effort be made to examine these matters in a consistent, scientific and balanced way. This led directly to the founding of the SPR in 188212, with Myers and Gurney only willing to join if Sidgwick would agree to be President.13

Annie Marshall

Meeting and falling in love with Annie Marshall had a profound impact on Myers’s emotional life, and her tragic death added depth and impetus to his survival researches.14 They met at irregular intervals over the years in London, where she attended several séances with him; also in the Lake District, where they walked on the grounds of the Marshall family homes at Hallsteads and Old Church. He provided her with moral support as she struggled to cope with her mentally-ill husband while at the same time bringing up their five children. Myers was particularly helpful to her in 1876 when Walter Marshall had finally to be confined to a psychiatric hospital because of his manic behaviour and reckless financial dealings.

In July of that year, Myers left for a tour of the Norwegian fjords with his brother Arthur. While he was away, Annie became increasingly guilt-stricken over her part in the confinement of her husband. She committed suicide on 29 August, cutting her jugular vein with scissors and then throwing herself into the lake. Myers was shattered. He subsequently idealized her memory: Annie became for him a symbol of the type of woman who, like Dante’s Beatrice, elevated her lover, by her beauty of body and soul, into the higher spiritual realms. There is no evidence that the relationship was at any time a physical one: indeed his poetry and prose suggest the reverse.15 Myers remained on good terms with Walter Marshall and his family until Walter’s death.16

Society for Psychical Research

Myers and Gurney invested great energy in fulfilling the aims of the society.17 However, unlike the Spiritualist members, who wished to investigate mediumship directly, they argued it was necessary first to map the full range of human mental abilities that are loosely called ‘normal’ before attempting to investigate the hypothesis of spirit survival.

Myers contributed to most of the early committees set up by the SPR to investigate mediumship, hauntings and apparitions, and suchlike. He took a particular interest in automatic writing, which he considered in relation to Gurney’s work in hypnosis and also to French experiments in the same field. He quickly came to postulate telepathy as having an important underpinning role, believing its existence to be highly likely on the basis of the SPR’s experiments with the Creery family, Smith and Blackburn, Guthrie18 and Lodge,19 and the accounts of spontaneous experiences that had been published in the SPR Journal and Proceedings.

Some years after they had started taking part in experiments, two of the Creery girls were caught cheating. However, Myers argued that the best of his and Barrett’s investigations with the family stood up. He had observed them closely in his home in Cambridge over a period of ten days; on a number of occasions the children were tested individually, a solid door dividing them from the researcher, and no member of the family knew the identity of the target object.20

The Blackburn-Smith investigation also became controversial when, following Myers’s death, Blackburn publicly alleged that he and Smith had faked the positive results. This is unlikely: Smith himself robustly denied the accusation; Blackburn’s personal life showed considerable indications of unreliability of character; and his account of how the cheating was done was inconsistent and contradictory (see Smith and Blackburn).

Telepathy, Automatic Writing, Hypnotism

In 1882 Myers coined the term ‘telepathy’, and this soon came to replace ‘thought-reading’ and other similar terms.21 He concluded that his and others’ researches offered at least some evidence that the mind was not totally dependent on the brain; he spent the rest of his life accumulating further supporting evidence in a wide range of areas, and in developing a provisional explanatory framework that linked apparently disparate behaviours and experiences together. For example, by 1883 he and Gurney were suggesting that what they called ‘crisis apparitions’ – those perceived of a person who was at the point of death or in great danger – were caused by a particular form of telepathy.22 (see Ghosts and Apparitions in Psi Research). Later he suggested that telepathic hypnotism could be the source of mesmeric action at a distance.23

Myers examined in great detail the role of telepathy in the origin of automatic writing24. He identified five possible sources for the writing:

- conscious will

- unconscious cerebration

- a higher faculty of one’s own mind

- telepathic contact with other incarnate minds

- discarnate spirits and extra-human intelligences.

He was cautious about invoking the fifth option, of discarnate intelligence, stating that he would only consider it in exceptional circumstances. He insisted on the need to beware of vague impressive language and of claims to expert knowledge. In one case which he described, the Reverend PH Newnham attempted to transmit thoughts in the form of questions to his wife to which she would respond by automatic writing using a planchette.25 Newnham obtained several hundred fairly relevant responses, and these suggested to him, and to Myers, the existence of a secondary self in Newnham’s wife, characterized by a certain low cunning and creativity, that communicated through telepathy. (Myers did not attend these sessions personally, but based his conclusions on his reading of Newnham’s private diary of 1871.)

It was while examining automatic writing that Myers fleshed out the general concept of automatisms that later formed a central aspect of his theory of the subconscious. He defined an automatism as follows:

[S]uch images as arise, as well as such movements as are made, without the initiation, and generally without the concurrence , of conscious thought and will. Sensory automatism will thus include visual and auditory hallucinations; motor automatism will include messages written without intention (automatic script) or words uttered without intention (as in “speaking with tongues,” trance-utterances, &c.). I ascribe these processes to the action of submerged or subliminal elements in the man’s being. Such phrases as “reflex cerebral action,” or “unconscious cerebration,” give therefore, in my view, a very imperfect conception of the facts.26

He stressed that these automatisms were independent, purposive structures and were not necessarily symptomatic of organic disease.27 On the contrary, the messages they contained could be of benefit to the conscious mind as advice or warnings (monitions).

Moreover, though such automatisms occurred only sporadically, or were induced artificially, there was an additional method of exploring the subliminal that was easily available to all: sleep and dream. Years before Freud, Myers stressed their importance as a method of accessing the unconscious as a source of creativity, of personal insight, and of telepathic content. He argued that dreams should be subjected to a far more intense analysis of their language and actual and symbolic content than they had had been in the past. Furthermore, we ‘ought to accustom ourselves to look on each dream, not only as a psychological observation, but as an observation which may be transformed into an experiment’.28 A careful record of dreams might indicate material of a telepathic or clairvoyant nature, as in the dream reported by Cyrus Read Edmonds about the collapse of the Thames Tunnel and the drowning of a workman.29

Parallel with his work on automatic writing went his investigations into hypnotism (though Gurney was the main experimenter in this field). For this purpose Myers made four visits to France between 1885 and 1887, the last on his own, the other three accompanied by his brother Arthur, a physician (Gurney was present on two of these visits).30 These encounters convinced him that hypnosis offered another powerful tool for experimental psychology and the study of supernormal phenomena. Both his direct experience and his wide reading confirmed his growing belief in the multiplex and plastic nature of consciousness. For example, in France, Pierre Janet’s experiments with the peasant housewife Léonie revealed that, under hypnosis, she displayed three separate personalities, while Auguste Voisin used hypnosis to transform a criminal lunatic into a competent nurse. On the other hand, Myers was mindful of the possibility of learned behaviour in these sorts of cases, and indeed suggested it as an explanation for Charcot’s hypnotic demonstrations.31

Early Opposition

Myers faced two main sources of opposition during these years. The first was from the medical community and the developing world of clinical and experimental psychology. He and Gurney were beginning to challenge the prevailing psychological orthodoxy of the day that was largely based on Carpenter’s theory of ‘unconscious cerebration’. In his Principles of Mental Physiology (1874), Carpenter asserted that the concept of mental reflexes adequately explained seemingly paranormal abilities.32 Such behaviours, later described by Myers and Gurney, were pathological at root, he argued; they had an internal or external physical cause, that loosened the grasp of the will and of reason, and led to automatic responses. This occurred especially where the individual was under the influence of a dominant idea or prejudice.33 However Myers and Gurney disputed the claim that unconscious cerebration provided a comprehensive explanation, finding evidence of a much richer, more creative and dynamic unconscious than it would allow. They argued that automatic writing and susceptibility to hypnosis were not in themselves symptoms of a pre-existing pathology; healthy, intelligent and balanced individuals might also possess these capacities and characteristics.34

The second major source of opposition was the Spiritualist community. Myers’s relationship with the Spiritualist movement during these years – and indeed throughout his life – was ambivalent35 On the one hand, his concepts of multiplex personality and telepathy appeared to undermine the Spiritualistic hypothesis. But on the other hand, as early as 1885 he could state:

My own conviction is that we possess – and can very nearly prove it – some kind of soul, or spirit, transcendental self ... which very probably survives the grave.36

However, he would not be specific about what he meant by ‘a spirit’. He believed that in certain circumstances some people had the ability to self-project from their bodies while alive, and be seen by others, and also that an apparitional phantasm of a person might be perceived both at the point of the person’s death, and sometimes long after death had occurred. But he would go no farther, describing such images as merely ‘the survival of a persistent personal energy’, not the ‘astral’ or the ‘etheric’ body described by the occultist or Spiritualist.37 And, though privately sympathetic to aspects of Spiritualism, in his work for the SPR he was merciless in exposing fraudulent professional mediums and their resolutely credulous clientele. He compared the latter to those simple-minded souls who always fell for the pleadings of beggars and the former (perhaps with memories of his dealings with the fake medium Anna Fay in mind) ‘vampires and Jezebels ... in their rapid transits through the sliding panel and the divorce court’.38

Given the work that Myers and Gurney put into gathering evidence of the kind described above, it was natural that Madame (Helena) Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society (TS) should attract their attention.39 Blavatsky seemed not only to have gathered examples of the same sort of unusual behaviours and experiences as the SPR, but also to have replicated them herself under certain conditions, allegedly through the support and teaching of her discarnate ‘Masters’. Myers was himself a member of the TS for a while and appeared at one stage to give credence to Blavatsky’s claims.40 However, the robust, if partially flawed, exposure of Blavatsky reported by his SPR colleague Richard Hodgson in 1885, changed his mind.41

Phantasms of the Living

The debunking of Blavatsky by the SPR came at a fortuitous moment, since it allowed Myers and his colleagues to retain credibility at a time when their reputation faced its first major public test: the publication of their two-volume work on apparitions, Phantasms of the Living.

Myers’s contribution to the book was minimal compared to Gurney’s. He wrote the introduction and a general paper on telepathic processes.42 Their views differed with regard to the role of telepathy in the generation of phantasms of the living when more than one person appeared to see the phantasm at the same time. Myers hypothesized that some personal energy detached from the body and impacted on the space where the originator of the phantasm imagined she/he was situated. And this radiant point of energy, or ‘phantasmogenetic’ focus, could be seen by more than one person if they possessed the appropriate sensibility.

Myers considered this to be a more credible explanation for the collective perception of phantasms than Gurney’s concept of telepathic infection. He invented the awkward term psychorrhagic diathesis to describe this capacity for projecting a phantasm that had a quasi-physical spatial impact. Not all his coinages were as felicitous as that of telepathy (though he compiled a useful psychical research dictionary which has acted as an interesting starting point for later work).43

Investigations of Spirit Mediums

Myers still found time to continue his investigation into mediumship and other unusual human abilities. This was somewhat limited, however. He never managed to sit with DD Home or with Stainton Moses in his physical circle (though in both cases, the former with William Barrett, he did write detailed assessments of them based on the documentary evidence at his disposal.44 His interest in physical mediums survived the disappointment of the 1870s and he had a number of sittings in the 1890s, most controversially with Eusapia Palladino. He agreed that fraud took place at the sittings in Cambridge in 1895 (though Cassirer has argued that the sittings were badly handled)45 but he still believed, as did the physicist and radio pioneer Oliver Lodge – over the strong objections of William James, Hodgson and the Sidgwicks – that on occasions she produced genuine psychokinetic effects.46

In addition, he became increasingly convinced of the veracity of certain ‘mental’ mediums (as opposed to ‘physical’ or séance mediums such as Palladino). In 1893 he made a presentation about the SPR and its work to the World’s Congress of Religions in Chicago, to great public acclaim,47 and on the return journey sat with the famous trance medium Leonora Piper in Boston.48 He also had positive experiences in personal sittings in London with Rosalie Thompson from 1898, and was further persuaded by the quality of sittings reported by other people with this medium.49

Investigations of Hauntings

Myers continued during these years to take part in the ‘traditional’ activity of the psychical researcher: the investigation of haunted houses. The most famous early example, the Cheltenham Ghost, was celebrated within psychical research circles – impressive for the detail of the record, the character of the main witness, and the number of individuals who witnessed the phantom.50 As Myers’s mother lived in Cheltenham it was convenient that he should investigate the case. He visited a number of key witnesses from May 1886 onwards, and despite some gaps and inconsistencies was impressed by the general coherence of their narratives. On the other hand, the 1897 investigation of a reputedly haunted house (Ballechin) in Perthshire, led by Ada Goodrich Freer and funded by the Earl of Bute, became an embarrassment to Myers, generating sceptical comment in the correspondence columns of The Times. Too many individuals were involved, and it emerged that the house had been rented under false pretences. Freer herself became antagonistic, implying that Myers believed privately that the house was haunted but was scared to admit it in public. She further damaged his reputation by innuendo, alleging a preference on Myers’s part for investigating women mediums rather than men.51

Freer did feel let down by Myers, but in this instance he was backed up by Frank Podmore, a SPR colleague who tended to espouse a sceptical standpoint on much psychical phenomena, and who stated that Myers was right ‘from the evidential standpoint’.52 Myers always acknowledged shortcomings in aspects of the Society’s work, but, in its defence, continually pointed out that psychical research was a new science, requiring the development of novel methods for emerging objects of study. He constantly reiterated its dispassionate and scientific approach to the issues, disassociating it from both Theosophy and Spiritualism.53

Development of Myers’s Ideas

In a powerful and substantial series of articles on the subliminal consciousness, Myers attempted to make sense of a wide variety of strange events and experiences, including some that he had personally witnessed.54 His method was to build an evidential base and argue incrementally, first from the normal to the abnormal, and only then, where the facts seemed to warrant it, to the supernormal. He eschewed labels such as ‘miracle’ and ‘magic’; for example, he and his physician brother Arthur debunked most of what they saw when they visited Lourdes.55 Instead, he argued that seemingly supernatural events would eventually be considered within the purview of an expanded science. His aim was to map and compare such cases empirically, in order to discover whether any over-arching concepts and theories might be generated that would provide insights into their fundamental nature and the conditions under which they might occur. If this could be done, he reasoned, it would encourage others to engage in more precise scientific experimentation.

Building on his work from the 1880s, Myers proposed the existence of a range of intelligences, or selves – of varying duration and permanence, each possessing its own memories and associations – that lay beneath the daily consciousness of everyday life. He further suggested that these had the power sometimes to impact on the daily consciousness and behaviour of the individual, either for good (evolutive) or ill (dissolutive) effect.

He stated: ‘I accord no primacy to my ordinary waking self, except that among my potential selves this one has shown itself the fittest to meet the needs of common life’.56 In other words, it had evolved, as suggested by his reading of Darwin, to cope with the struggle for survival. He believed that a barrier lay between this everyday consciousness (the supraliminal) and unconscious processes (the subliminal). Under certain circumstances, this barrier could be penetrated by the psychological automatisms outlined above, either because of unusual permeability in the individual, or the impact of traumatic events,or through the use of automatic writing, hypnosis, self-induced trance, crystal vision – or a combination of these.

Myers saw three broad divisions in the subliminal: the autonomic, which dealt with unconscious physiological processes; the hypnotic, a powerful stratum that responded positively or negatively to suggestions coming from external sources or from the workings of its own imagination faculty; and the higher subliminal, the source of inspiration, creativity and spirituality. It should be noted that some psychologists of the time found this combination of rubbish dump and treasure house especially hard to accept, even including William James, who was otherwise broadly sympathetic to Myers’s ideas.57

Myers eventually went farther, arguing that, as the supraliminal consciousness relaxed its control, or was circumvented, access to the power of the subliminal and its energies became available for the good of humankind. In some way, Myers suggested, these energies and faculties related to that part of the subliminal self which linked to the transcendental world: ‘We shall recognize a relation – obscure but indisputable – between the subliminal and the surviving self’.58

It was this concept of a subliminal life embracing and creating all the anomalous phenomena that Myers investigated that helped to create order and coherence out of a vast body of obscure, sometimes distasteful, sometimes transcendental, fleeting and inchoate material. It established Myers’s early reputation amongst psychologists predisposed to a psychodynamic approach. As James stated:

Meanwhile, descending to detail, one cannot help admiring the great originality with which Myers wove such an extraordinarily detached and discontinuous series of phenomena together. Unconscious cerebration, dreams, hypnotism, hysteria, inspirations of genius, the willing-game, planchette, crystal-gazing, hallucinatory voices, apparitions of the dying, medium-trances, demoniacal possession, clairvoyance, thought-transference – even ghosts and other facts more doubtful ... Yet Myers has actually made a system of them, stringing them continuously upon a perfectly legitimate objective hypothesis, verified in some cases and extended to others by analogy. 59

This attempt to develop a theoretical framework came at a price. First, Myers was not always consistent in his use of terminology. At different times he deployed the terms ‘individuality’, ‘personality’, ‘supraliminal self’, ‘subliminal self’ and ‘subliminal selves’, in slightly different ways; it was uncertain how these concepts related to each other or to the more traditional ones of ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’. Also, there was confusion as to whether he viewed the personality as being in essence a single entity or dual and possibly multiple ones.

Greater clarity can be achieved, as Emily Williams Kelly points out,60 by using the term ‘subliminal self’ to describe the fundamental, unifying, core principle of individuality – or larger self – that exists in both the incarnate and discarnate world, and which in the discarnate world is therefore spirit/soul. The term ‘subliminal selves’ might then be used solely to describe the varying selves, the chains of memory/personality that bubble in and out of everyday empirical consciousness, the supraliminal.

A second confusion arises from the associations connected with the word ‘subliminal’. The term originally meant ‘going across, or under, the threshold or lintel’. Myers, at times, used ‘intra-’, ‘extra-’ or ‘ultra-marginal’ to avoid both the spatial associations of ‘above’ and ‘below’ and any implications of superiority and inferiority, both of which he recognized could mislead. He tried a range of metaphors to get round this problem: probably the most effective is: ‘The threshold ... must be regarded as a level above which waves may rise – like a slab washed by the sea – rather than as an entrance into a cave.’61

Myers’s argument, at least in outline, possesses an impressive cumulative coherence, and this underpins his belief in survival.62 First he discussed telepathy as an indication that consciousness could function independently of body, and then, with this established, proposed it as a potential mechanism for two-way communication between the living and the dead. He argued that in special circumstances, where the psychic membrane was unusually permeable – as occurred with trance mediums such as Leonora Piper – telepathic communication could occur that enabled not merely the type of fleeting, spontaneous contact typical of a sensory or auditory hallucination, but a sustained two-way conversation offering evidential proofs of survival.

Such proofs should fulfil two criteria before they could be accepted as genuine: ‘first the need of definite facts, given in the messages, which were known to the departed and are not known to the automatist; and secondly, the need of detailed and characteristic utterances; a moral means of identification corresponding, say, not to the meagre signalement by which a man is described on his passport, but to the individual complex of minute markings left by the impression of a prisoner’s thumb’.63 Yet here too he remained cautious, asking, ‘May not that knowledge be gained ... clairvoyantly or telepathically with no intervention of any spirit other than that of a living man?’64

Achievements and Tributes

One of Myers’s achievements was to endow the field of psychical research with greater visibility, status and respectability. He was an outstanding and fluent lecturer, requiring little preparation thanks to an excellent memory and superlative powers of organisation and expression. He excelled at recounting striking incidents that had made a particular impression on him, such as ‘Peak in Darien’ experiences, where a dying person is visited by a person they did not know was dead65 and ‘Compact’ cases, where a person before death pledges to return to a particular friend or family member after death, and keeps that promise.66 Like Sidgwick, he continually urged on the public the value of sending well-recorded and corroborated evidence to the Society. He attended all but one of the international congresses on psychology between 1889 and 1900, and made valuable contributions to them.67

Together with Gurney, Myers played a considerable part in overcoming the medical profession’s entrenched opposition to the existence and therapeutic potential of hypnotism in a clinical context; the pair also drew the attention of British and American psychologists to the work of their counterparts in continental Europe, notably Charcot, Bernheim, Breuer and Freud. In this field he cannot be dismissed as a mere dilettante. As Gauld points out, the nearly two hundred pages devoted to hypnotism in Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death are invaluable as a source of accurate references to nineteenth-century hypnotic literature, ‘particularly that of continental Europe, which he probably knew better than any other British or American writer of the time.’68

William Crookes, Oliver Lodge and Charles Richet (scientists with international reputations, the first two members of the Royal Society, the last a future Nobel prize winner) valued him highly, and impressive tributes from Europe and America were forthcoming after his death. As Crabtree states, Myers was at that time the only writer to be promoting a psychological, rather than physiological, view of automatisms; his ideas profoundly influenced the thinking of the great French psychologist Pierre Janet. The sheer intellectual and physical effort he put into his work made a considerable impact in sympathetic psychological circles, and the degree to which he had reinvented himself in order to achieve this was recognized.69

William James wrote:

Myers had as it were to re-create his personality before he became the wary critic of evidence, the skilful handler of hypothesis, the learned neurologist and omnivorous reader of biological and cosmological matter, with whom in later years we were acquainted .70

Theodore Flournoy wrote:

By means of intense application, seconded by an enormous power of work and exceptional brilliancy, he nevertheless forced himself to become the rigorous scientist; and in biology, psychology, and other sciences he possessed almost the knowledge of a specialist ...71

Aldous Huxley wrote:

How strange and how unfortunate it is that this amazingly rich, profound and stimulating book should have been neglected in favor of descriptions of human nature less complete and of explanations less adequate to the given facts.72

Favourable comments have come from present-day writers, including Canadian philosopher Ian Hacking, who wrote:

The most careful summaries of the entire nineteenth-century multiple literature are to be found in the writings of F.W.Myers, a cofounder of the Society for Psychical Research in London - especially his magnum opus [Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death].73

American psychologist James Carpenter wrote:

One of the great founders of psychical research, F.W.H. Myers bequeathed to all subsequent researchers a conception of unconscious mental functioning that was almost equal in scope to that developed more elaborately by Sigmund Freud ... The importance of his model of unconscious functioning for understanding psi processes has been re-examined recently in the light of current thinking in psychology and neurology, as well as century of new observations of paranormal processes, and is revealed as fresh and heuristically vital.74

Myers also helped shape the ideas of Assagioli,75 Jung76 and others in the early history of psychodynamic theories of the mind.

It has also been suggested that Myers’s thought significantly influenced a wide range of writers, among them many of the first rank such as Ruskin, Yeats, Henry James, DH Lawrence and Aldous Huxley, and the less well-known novelists May Sinclair and JD Beresford.77 These writers held various degrees of belief in the paranormal and took only what they needed for literary purposes. (Compare, for example, the different approaches of Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson and Henry James.)78 Myers’s influence can also be found in contemporary cultural and literary scholarship.79

Scepticism

Given the incompatibility of Myers’s claims and arguments with orthodox science it is inevitable that he should have faced hostile criticism, both during his life and to the present day. The interest shown by William James and some others in his thought was not shared by psychologists within the more strongly physiological tradition.80 Notably, Human Personality has never been translated into German.81 Even within the developing psychodynamic movement, the reactions were of hostility and indifference. It was not until late in the twentieth century that his work was recognized as offering substantial value to the discipline of transpersonal psychology.82

Nor have his ideas had much impact on mainstream psychology. Some psychologists in recent years have discussed the concept of automatisms in the context of virtual agency83 and the power of the adaptive unconscious;84 however, these tend to echo Carpenter’s concept of unconscious cerebration. There has been no serious attempt to assess the richly detailed examples of automatism that, for many people, have provided persuasive evidence of the independence of consciousness from its neurophysiogical substrate, and even for some form of post-mortem survival. These include the ‘cross-correspondences’ that began to appear in automatic writings shortly after Myers’s death, and which have been seen as attempts by the deceased Myers and certain of his colleagues to confirm the fact of their survival.85

While his work has been useful to historians of dissociative identity disorder, and abnormal psychology in general, Myers’s specific claims with regard to telepathy – and the apparent ability of some mediums to access information beyond the normal sensory framework – have been largely ignored. Nor has his conceptual framework been operationalized for testing in a controlled environment.

Some historians have argued, with varying degrees of subtlety, that he allowed his existential angst to distort his findings. As a clergyman’s son (as also were Henry Sidgwick and Gurney), it is suggested that his underlying motivation was to restore the spiritual dimension lost through the rise of scientific materialism and the scholarly undermining of the literal truth of the Bible. For example, Janet Oppenheim acknowledges the originality and creativity of his mind, but complains that it ‘always worked its way back to the soul’; also that most contemporary psychologists disliked the assurance with which he claimed the endorsement of science for his personal beliefs.86 Yet like many such critics, Oppenheim fails to fully appreciate Myers’s scrupulousness with regard to the examination of evidence and his care, on most occasions, to distinguish his personal beliefs from what could be scientifically verified.

Another approach – one commonly used against psychical researchers – is to seek to discredit him on the basis of human failings. In Myers’s case, much is made of alleged sexual improprieties – homosexual affairs, adulterous escapades with female mediums whom he investigated – and also of his infatuation with a married woman, with the dual implication that he not only betrayed her husband Walter Marshall, a cousin of his, but added to the intolerable emotional pressures on her that caused her to take her life.87

Myers was no saint. As a young man he could be arrogant, snobbish and opinionated. He liked the company of beautiful and intelligent young men and women, and he certainly had intense male friendships, though there is no significant evidence that these were physical. As his reputation grew, he enjoyed weekending in stately houses. However, he was a diligent and devoted husband and father (though in some ways, his son Leopold later said, a rather overbearing one).88 There is no convincing evidence that he had affairs with any of the women mediums he investigated. Nor has it been demonstrated that Myers’s personal failings – real or imagined – are relevant to a judgement of his professional work.

Modern Re-evaluations

In recent years powerful support for Myers has come from the group of scholars led by Edward F Kelly and Emily Williams Kelly (née Cook) who in 2007 published Irreducible Mind, an attempt to interpret his ideas within a modern framework and in the light of new scientific research. The book assembles in scholarly detail an impressive body of evidence that has accumulated in the areas that Myers put forward to substantiate his model of the Subliminal Self, such as genius, mystical experience and telepathy, and also in new areas that have subsequently developed notably out-of-body and near-death experiences.

The authors propose a psychological model based on Myers’s ideas – and also William James’s ‘transmission’ theory of mind, which owes something to the permeability of Myers’s concept of the threshold – challenging what they see as the dominant materialist and reductive view of mind and suggesting promising areas of research.

Of particular value in this context is a chapter by Emily Kelly89 which assembles abundant empirical evidence appearing to show the mind influencing physiological processes – placebo effects, removal of warts, stigmata, etc – and thus indicating some degree of independence from the body. The book also refers to the decades of research into memories of a previous life carried out by the psychiatrist Ian Stevenson, a topic which, like near-death experiences, emerged decades after Myers’s death.90 Interestingly, Myers remarked that ‘for reincarnation there is no valid evidence’, reflecting the lack of work of Stevenson’s quality at the time.

In addition, the revival of research into mental mediumship in recent years by Gary Schwartz, Emily Kelly, and Julie Beischel appears to provide further support for the survival hypothesis.91 In this context, there has been an application of Myers’s theory of the Subliminal Self to the highly ambiguous field of alleged spirit release or possession, an extension Myers would surely have approved of, if explored with common sense, sensitivity and caution.92 He himself was always careful to distinguish between pseudo-possession as typified by the case of Lurancy Vennum (the ‘Watseka Wonder’) and the best of Leonora Piper’s trance evidence.93

It should be acknowledged that the evidence put forward for the existence of paranormal phenomena, past and present, is robustly contested by certain sections of the intellectual community.94 Irreducible Mind has been further criticized for putting forward an over-simple dichotomy between materialist reductionism on the one hand and interactive dualism on the other, which, it is argued, does not reflect more recent specialist research.95 However, such views would carry greater weight if the critics were able to show they had directly engaged with the vast amount of parapsychological material cited in the book.

The controversial nature of Myers’s visionary ideas should by no means obscure his commitment to the ideals of science as the central method for accumulating knowledge. He clearly stated:

The method to which I refer is that of experimental psychology in its strictest sense – the attempt to attack the great problems of our being not by metaphysical argument, nor by merely introspective analysis, but by a study, as detailed and exact as any other natural science, of all such phenomena of life as have both a psychical and a physical aspect. 96

Myers the scientist was energetic, rigorous and scrupulous: he built up his knowledge base, recorded experiences accurately and in detail, and examined them against objective criteria.97 The Society for Psychical Research itself was modelled on the practice of the learned societies of the time, key features of which were the publication of findings in a scholarly format and a willingness to accept and respond to informed criticism (see Society for Psychical Research). Myers also strongly believed in developing appropriate methods for psychical research as a new field of study, as was common in any new scientific enterprise: in this case, automatic writing, hypnotism and trance mediumship, and refinements on these, along with others such as crystal gazing, on which he experimented with psychic subjects and which in some ways anticipated the modern ganzfeld and psychomanteum techniques adopted by experimental parapsychologists in recent decades.98 He labelled these methods ‘psychoscopes’. Just as telescopes, microscopes and spectroscopes had developed to deal with the physical world, these new techniques were necessary to explore the world of the psyche.99

In short, Myers was not ‘magical’ or ‘occult’ in his approach and practices. On the contrary, he fully accepted the principles and methodology of science, along with its accumulated body of knowledge: he merely argued for its extension into a difficult and not easily quantifiable area.100

It is true that Myers had little expertise in laboratory work. He believed, as did William James,101 that the sustained study of the broad range of mental behaviours of a gifted psychic subject would yield more meaningful results than more narrowly-focused physiological measurements; as would the careful direct observation, recording and comparison of spontaneous naturally-occurring incidents. Indeed, Edward Kelly has stressed the validity of this approach and its expansion in the twenty-first century.102 He points out that laboratory-based research is only one of the scientific methodologies available, and that the accurate recording, analysis and comparison of large numbers of individual case studies offer an equally rigorous approach, one which may generate insights and relationships missed by the former.

Myers’s Vision

For Myers, science ultimately had a cosmic purpose. He came to believe that telepathy was a fundamental structural law of the universe, but made no pretence of understanding its modus operandi. He said ‘I doubt indeed, whether we can safely say of telepathy anything more definite than this: Life has the power of manifesting itself to life.’103 At the end of Human Personality, he outlined a highly imaginative Scheme of Vital Faculty in which varying modes of telepathic interaction took place at different levels between the living and the dead, as part of humanity’s endless spiritual progression.104 As Kripal has well expressed,105 Myers believed in evolution on two levels – the Darwinian or incarnate, and the Neo-Platonic or metetherial; he thought of the Supraliminal Self as embodying struggle in this world, and the Subliminal as a vehicle for spiritual progression in the next.

According to this model, in the transcendental or metetherial state the Subliminal Self can access supernormal faculties beyond our current stage of evolution. It can bring down from the transcendental world at birth – or later gain access by means of subliminal ‘uprushes’ – the spiritual gifts of the saint, the creative insights of the poet, the genius of the musician or mathematician, for example. But evolution does not stop there. As Lodge stated in his memorial address on Myers: ‘Infinite progress, infinite harmony, infinite love, these were the things which filled and dominated his existence.’106

Myers’s vision for humankind, in this world and the next, was at once hugely optimistic and challenging. He set his face against the pessimistic degeneration philosophies that gained some popularity in cultural and scientific life in the late nineteenth century.107

Human Personality offers cosmic sweep and ambition. It explicitly poses the question ‘for man most momentous of all ... whether or not he has an immortal soul; or .... whether or not his personality involves any element which can survive bodily death. 108 The large and complex body of evidence that it marshals, skilfully shaped and coordinated in a relational hierarchy, includes examples – for instance from the mediumship of William Stainton Moses and Leonora Piper – of a quality to suggest that a human’s individual personality – and not just a psychic fragment – survives with its love, disposition and idiosyncrasies all intact. In short, the book has indeed convinced many people that there is some faculty in the human personality that exists independently of the body and that this might survive bodily death. Some might have thought, given this, that Myers would have returned to the established church. But his relationship with Christianity was complex and, at times, rather fraught.109

Conviction of Survival

And yet Human Personality also ends in something of an anticlimax: it says nothing explicitly about what it was that convinced Myers personally of survival of consciousness. We know that he was persuaded by the sittings he held with Piper and Rosalie Thompson – one hundred and fifty or more with the latter.110 Yet his conclusions about these are absent, and few of the original notes have survived. The only records in the Myers’s archive at Trinity (apart from some sketchy notes on his visit to a Parisian medium in the 1870s) that exist are those of Mrs Myers’s sitting with Mrs Piper in early 1902.

Myers was deeply impressed by Thompson who, unlike some séance mediums, was a normal, balanced individual, and who, unlike Piper, appeared able to communicate in only a light trance. In her work he saw an exemplar of a more effective style of communications that might be possible in the future, the result of combined terrestrial and transcendental evolutionary forces.111

According to Alice James, William James’s wife, Myers had no interest in Mrs Thompson other than in her abilities as a medium.112 Mrs Myers’s hostility towards her seems to have been a result of her general possessiveness rather than sexual jealousy. There is little doubt that she destroyed the records of the sittings, and she allowed only a highly expurgated version of Myers’s autobiography to be published in her lifetime.113 For this reason there is no way of assessing the quality of the evidence that Myers received from the ‘discarnate spirit’ of Annie Marshall. However, an account of this interaction does exist, in a letter to William James in 1899:

That spirit with great difficulty descended into possession of the sensitive’s organism & spoke words which left no doubt of her identity ... And when Mrs Thompson came to herself [she said] ... I seem to have been taken to heaven by an angel.

Thompson was never paid for her mediumship (her husband was a successful businessman), and one reason she was always willing to sit for Myers, he said, was the quality – the almost heavenly quality – of the experiences she had when Annie Marshall communicated.114

It should be stressed that Eveleen Myers was fully aware of Myers’s relationship with Annie Marshall. Myers had told her about it at the time of their courtship and marriage. The statements of Blum and Berger on this subject are incorrect. She was a highly possessive woman, but she was also trying to protect her husband’s reputation and that of members of the Marshall family who were still alive.115

Conclusion

Myers’s imperfections should not distract from the full richness of his work and ideas, which remain to be fully explored and applied in current clinical and experimental contexts (though it could be argued that his theory has enjoyed increased influence in recent years – for example, in studies of altered states of consciousness).116

In his writings he was guilty at times of a sonorous woolliness of language and it is true, as Gauld has said, he does not so much explain paranormal experiences and capacities as indicate where an explanation of them might be sought.117 Nevertheless, his work bristles with insights. It has been fairly said of him that he was the Coleridge of psychical research.118

Finally, one must stress his sheer courage, drive and sacrifice (given the other opportunities available to a man of his status and gifts) in tackling such a marginalized and low status field of study, and in risking the real possibility of being deceived and made to look foolish. His claims for himself were modest but his vision for the human race was cosmic. Regardless of the high-flown language and transcendental perspective, many (though certainly not all) of those who have studied his work carefully would agree with Edward Kelly’s assessment that the system of psychology that he and William James may be said to have founded remains unrivalled in its relentless commitment to empirical rigour on the one hand, and on the other, the courage it showed in embracing ‘the supernormal and transpersonal phenomena that are essential to a fuller understanding of human mind and personality.’119

Select Bibliography

Hamilton’s biography contains a detailed list of sources for Myers’s life and times, including those that evaluate both the positive and negative aspects of his character and actions. This may be supplemented with the more detailed bibliographies in Irreducible Mind which provide substantial evidence for the anomalous phenomena that Myers investigated. The best account of Myers’s relationship with Annie Marshall is in Beer (1998). Valuable contextual material on Myers’s times is in Oppenheim (1985) and Gauld (1968). Carlos Alvarado (2003, 2009, & 2014) has done extensive work on the reception of Myers’s book and on his work and ideas in context of the development of nineteenth century psychology. See, in addition, Sommer’s Ph.D. thesis (2013) on this latter theme; and also EW Kelly (2001). Alvarado’s blog contains much relevant background material. EW Kelly’s Ph.D. thesis on Myers (1992) is still of central relevance. Two reviews of Irreducible Mind are cited: one partly critical, Ash, Grundlach and Sturm (2010), and one positive, Kennedy (2006).

Trevor Hamilton

Literature

Alvarado, C.S. (2003). On the centenary of Frederic W.H. Myers’s Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death. Journal of Parapsychology 68, 3-43.

Alvarado, C.S. (2009). Frederic W.H. Myers, psychical research and psychology: An essay review of Trevor Hamilton’s Immortal Longings: F.W.H. Myers and The Victorian Search For Life After Death. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 73, 150-69.

Alvarado, C.S. (2014). Vignettes on Frederic W.H.Myers. Paranormal Review, 3-13.

Ash, T., Grundlach, H., & Sturm, T. (2010). Review of Irreducible Mind: Towards a Psychology for the 21st Century. American Journal of Psychology 123/2, 246-50.

Assagioli, R. (1965, 1993). Psychosynthesis. A Manual of Principles and Techniques. London: Aquarian Press.

Beer, J. (1998). Providence and Love: Studies in Wordsworth, Channing, Myers, George Eliot and Ruskin. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Beischel, J. (2007). Contemporary methods used in laboratory-based mediumship research. Journal of Parapsychology 71, 37-68.

Berger, A.S. (1988). Lives and Letters in American Parapsychology. A Biographical History, 1850–1987. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Blum, D. (2006). Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death. New York: Penguin Press.

Broad, C.D. (1953, 2001). Religion, Philosophy and Psychical Research: Selected Essays. Abingdon and New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Broad, C.D. (n.d.). Papers, Trinity College Library, Cambridge, D/17.

Cardeña, E.m & Winkelman, M., eds. (2011). Altering Consciousness. Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Vol. 1: History, Culture, and the Humanities. Santa Barbara, California, USA: Praeger.

Carpenter, J.C. (2012). First Sight: ESP and Parapsychology in Everyday Life. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman & Littlefield.

Cassirer, M. (1983). Palladino at Cambridge. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 52, 52-58.

Collins, A. (1948). The Cheltenham Ghost. London: Psychic Press.

Cook, E.W. [Kelly]. (1992). The Intellectual Background and Potential Significance of F.W.H. Myers’s Work in Psychology and Parapsychology. Ph.D. thesis. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Cook, E.W. [Kelly] (1994). The subliminal consciousness: F.W.H. Myers’s approach to the problem of survival. Journal of Parapsychology 58, 39-51.

Crabtree, A. (2003). ‘Automatism’ and the emergence of dynamic psychiatry. Journal of the History of the Behavioural Sciences 39, 51-70.

Flournoy, T. (1911). (trans. Carrington, H.) Spiritism and Psychology. New York and London: Harper.

Freud, S. (1912). A note on the unconscious in psychoanalysis. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 26, 312-18.

Gauld, A. (1964). Frederic Myers and ‘Phyllis’. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 42, 316-23.

Gauld, A. (1965). Mr. Hall and the S.P.R. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 43, 53-62.

Gauld, A. (1966). [Reply to the pamphlet Dr Gauld and Mr. Myers by Archie Jarman]. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 43, 277-81.

Gauld, A. (1968). The Founders of Psychical Research. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Gauld, A. (1992, 1995). A History of Hypnotism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gurney, E., & Myers, F.W.H. (1883a). Phantasms of the living. Fortnightly Review 39, 562-77.

Gurney, E. & Myers, F.W.H. (1883b). Transferred impressions and telepathy. Fortnightly Review 39, 437-52.

Guthrie, M., & Birchall, J. (1883). Record of experiments in thought transference. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 1, 263-83.

Hacking, I. (1995). Rewriting the Soul. Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hall, T.H. (1964, 1980). The Strange Case of Edmund Gurney. London: Duckworth.

Hall, T.H. (1968, 1980). The Strange Story of Ada Goodrich Freer. London: Duckworth.

Hall, T.H. (1968). The Strange Case of Edmund Gurney. Some comments on Mr. Fraser Nicol’s review. International Journal of Parapsychology 10, 149-64.

Hamilton, T. (2009). Immortal Longings: FWH Myers and the Victorian Search for Life after Death. Exeter: Imprint Academic.

Hamilton, T. (2011). Myers and the synthetic society: Christianity and psychical research, a historical case study. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Churches’ Fellowship for Psychical and Spiritual Studies, University of Exeter.

Hamilton, T. (2013). F.W.H. Myers, William James, and Spiritualism. In The Spiritualist Movement: Speaking with the Dead in America and Around the World ed. by C. Moreman. Santa Barbara, California, USA: Praeger, 97-114.

Huxley, A. (1961). Foreword to Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death ed. by S. Smith (abridged). New York: University Books, 7-8.

James, W. (1901). Frederic Myers’s service to psychology. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 17, 1-23.

James, W., Lodge, O., Flournoy, T., & Leaf, W. (1903–1904). [Reviews of Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death]. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 18.

Jarman, A. (1964). Dr. Gauld and Mr. Myers. Hertfordshire: privately printed.

Johnson, G.M. (2006). Dynamic psychology in modernist British Fiction. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kelly, E.W. (2001). The contributions of F.W.H. Myers to psychology. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 65, 65-90.

Kelly, E.F., Kelly, E.W., Crabtree, A., Gauld, A., Grosso, M., & Greyson, B. (2007). Irreducible Mind: Towards a Psychology for the 21st Century. Lanham, Maryland, USA: Rowman and Littlefield.

Kennedy, J.E. (2006). Review of Irreducible Mind. Journal of Parapsychology 70, 373-77.

Kripal, J.J. (2010, 2011). Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Lambert, G.W. (1969). Stranger things: Some reflections on reading ‘Strange Things’ by John L. Campbell and Trevor H. Hall. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 45, 43-45.

Lodge, O. (1913). Report on a Case of Telepathy. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 16, 114-18.

Lodge, O. (1930). Conviction of Survival. Two Discourses in Memory of FWH Myers. London: Methuen.

Lodge, O., Myers, F.W.H., van Enden, F., Wilson, J.O., Hodgson, R., Johnson, A., Verrall, A.W. (1901–1903). Reports of sittings with Mrs Thompson. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 17, 61-244.

Luckhurst, R. (2002). The Invention of Telepathy 1870–1901. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Moody, R. with Perry, P. (1993). Reunions: Visionary Encounters with Departed Loved Ones. New York: Villard Books.

Myers, A.T., & Myers, F.W.H. (1893–1894). Mind-cure, faith-cure, and the miracles at Lourdes. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 9, 160-209.

Myers, F.W.H. (1884). On a telepathic explanation of some so-called spiritualistic phenomena. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 2, 217-37.

Myers, F.W.H. (1884-5). Specimens of the cases for ‘Phantasms of the Living’. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 1, 114-30.

Myers, F.W.H. (1885a). Automatic writing-II. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 3, 1-63.

Myers, F.W.H.(1885b). Human personality in the light of hypnotic suggestion. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 4, 1-24.

Myers, F.W.H. (1886a). Introduction. In Phantasms of the Living (2 vols.) by E. Gurney, F.W.H. Myers, & F. Podmore. London: Trubner, Vol. 1, xxxv-lxxi.

Myers, F.W.H. (1886b). Note on a suggested mode of psychical interaction. In Phantasms of the Living (2 vols.) by E. Gurney, F.W.H. Myers, & F. Podmore. London: Trubner, Vol. 2, 277-316.

Myers, F.W.H. (1886c). On telepathic hypnotism, and its relation to other forms of hypnotic suggestion. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 4, 127-88.

Myers, F.W.H. (1887a). Automatic writing-III. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 4, 209-61.

Myers, F.W.H. (1887b). Multiplex personality. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 4, 496-514.

Myers, F.W.H. (1888a). French experiments on the strata of personality. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 5, 374-97.

Myers, F.W.H. (1888b). The work of Edmund Gurney in experimental psychology. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 5, 359-73.

Myers, F.W.H. (1889a). Automatic writing-IV: The daemon of Socrates. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 5, 522-47.

Myers, F.W.H. (1889b). [Review of Automatisme Psychologique by Pierre Janet]. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 6, 186-99.

Myers, F.W.H. (1889c). On recognized apparitions occurring more than a year after death. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 6, 13-65.

Myers, F.W.H. (1890). A defence of phantasms of the dead. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 6, 314-57.

Myers, F.W.H.(1892a). The subliminal consciousness. Chapter 1: General characteristics and subliminal messages. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 7, 298-327.

Myers, F.W.H. (1892b). The subliminal consciousness. Chapter 2: The mechanism of suggestion. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 7, 327-55.

Myers, F.W.H. (1893a). The Congress of Psychical Science at Chicago. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 6, 126-29.

Myers, F.W.H. (1893b). Science and a Future Life with Other Essays. London: Macmillan.

Myers, F.W.H. (1893c). The subliminal consciousness. Chapter 6: The mechanism of hysteria. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 9, 3-25.

Myers, F.W.H. (1894). The experiences of W. Stainton-Moses-I. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 9, 245-352.

Myers, F.W.H. (1895a). The experiences of W. Stainton-Moses-II. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 11, 24-113.

Myers, F.W.H. (1895b). Reply to Dr Hodgson. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 7, 55-64.

Myers, F.W.H. (1895c). Hysteria and genius. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 8, 51-8, 69-70.

Myers, F.W.H. (1895d). Resolute credulity. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 11, 213-34.

Myers, F.W.H. (1900). Presidential address. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 15, 110-12.

Myers, F.W.H. (1901). In memory of Henry Sidgwick. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 15, 452-62.

Myers, F.W.H. (1903, 1904). Human Personality and Its Survival of Bodily Death (2 vols.). London and New York: Longmans.

Myers, F.W.H. (1904). Fragments of Prose and Poetry Edited By His Wife Eveleen Myers. London: Longmans.

Myers, F.W.H. (n.d.). Papers. Trinity College Library, Cambridge, 12/170.

Myers, F.W.H., & Barrett, W.F. (1889). [Review of D.D. Home, His Life and Mission by Mme. Home]. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 4, 101-36.

Nicol, F. (1966). The silences of Mr Trevor Hall. International Journal of Parapsychology 8, 5-59.

Nicol, F. (1972). The founders of the SPR. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 55, 341-67.

Oppenheim, J. (1985). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England 1850–1914. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Owen, A. (2004). The Place of Enchantment. British Occultism and the Culture of the Modern. Chicago, Illinois, USA: University of Chicago Press.

Palmer, T. (2012). Revised Epistemology for an Understanding of Spirit Release Therapy Developed in Accordance with the Conceptual Framework of F.W.H. Myers. Ph.D. thesis. Bangor, Wales, UK: University of Wales.

Pick, D. (1989, 1996). Faces of Degeneration: A European Disorder c1848–c1918. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Podmore, F. (1900–1901). [Review of The Alleged Haunting of B-House by Lord Bute and A. Goodrich-Freer]. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 15, 98-100.

Price, L. (1985). Astral bells in Notting Hill. Theosophical History 1, 25-35.

Price, L. (1986). Madame Blavatsky unveiled? A new discussion of the most famous investigation of the Society for Psychical Research. London: Theosophical History Centre.

Radin, D. (1997). The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena. San Francisco: Harper.

Rational Wiki. F.W.H. Myers. [Web page.]

Rimmer, W.G. (1960). Marshalls of Leeds: Flax Spinners 1788–1886. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ryan, M.B. (2010). The resurrection of Frederic Myers. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology 42, 149-70.

Saltmarsh, H.F. (1938, 1975). Evidence of Personal Survival From Cross Correspondences. New York: Arno Press.

Shamdasani, S. (2003, 2004). Jung and the Making of Modern Psychology: The Dream of a Science. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Sidgwick, E. (1886). Results of a personal investigation into the physical phenomena of spiritualism, with some critical remarks on the evidence for the genuineness of such phenomena. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research 4, 45-74.

Skrupskelis, I.K., & Berkeley, E.M. (1994) (eds.) The Correspondence of William James, Vol. 3. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University of Virginia.

Skrupskelis, I.K., Berkeley, E.M., & Bradbeer, W. (2001) (eds.) The Correspondence of William James, Vol. 9. Charlottesville, Virginia, USA: University Press of Virginia.

Smith, J.C. (2010). Pseudoscience and Extraordinary Claims of the Paranormal: A Critical Thinker’s Toolkit. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 253-55, 251-52, 238-40.

Sommer, A. (2013). Crossing the Boundaries of Mind and Body: Psychical Research and the Origins of Modern Psychology. Ph.D. thesis. London: University of London.

Taylor, E. (1996). William James on Consciousness Beyond the Margin. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press.

Taylor, E. (2009). The Mystery of Personality: A History of Psychodynamic Theories. New York: Springer.

Thurschwell, P. (2001). Literature, Technology and Magical Thinking 1880–1920. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, F.M. (1974). Between Science and Religion: The Reaction to Scientific Naturalism in Late Victorian England. Newhaven and London: Yale University Press, 104-33.

Waller, D. (2009). The Magnificent Mrs Tennant. Newhaven and London: Yale University Press.

Wegner, D.M. (2004). The Illusion of Conscious Will. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Bradford Books.

Wikipedia. F.W.H. Myers. [Web page.]

Wiley, B.H. (2005). The Indescribable Phenomenon: The Life and Mysteries of Anna Eva Fay. Seattle, Washington, USA: Hermetic Press.

Wiley, B.H. (2012). The Thought Reader Craze. Victorian Science at the Enchanted Boundary. Jefferson, North Carolina, USA: McFarland.

Williams, J.P. (1984). The Making of Victorian Psychical Research: An Intellectual Elite’s Approach to the Spiritual World. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

Wilson, T.D. (2009). Strangers to Ourselves: Discovering the Adaptive Unconscious. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Belknap Press.

Endnotes

- 1. Rimmer (1960).

- 2. Hamilton (2009), 9-41.

- 3. Waller (2009).

- 4. Myers (1903, 1904).

- 5. Turner (1974), 104-33.

- 6. Myers (1900), 110-12.

- 7. Broad (1953, 2001), 89.

- 8. Gauld (1968), 104.

- 9. Sidgwick (1886), 70-72.

- 10. Wiley (2005), 139-45.

- 11. Myers (1895b), 55-64.

- 12. Hamilton (2009), 111-12.

- 13. Broad (1953, 2001), 93. See also Myers (1901), 452-62.

- 14. Beer (1998).

- 15. Beer (1998), 143-88.

- 16. Hamilton (2009), 287.

- 17. Nicol (1972), 341-67; Cook (1994), 39-51.

- 18. Guthrie & Birchall (1883).

- 19. Lodge (1913).

- 20. Hamilton (2009), 118-22. See also Wiley (2012), and Broad (n.d.).

- 21. Myers (n.d.).

- 22. Gurney & Myers (1883a), 437-52; Gurney & Myers (1883b), 562-77.

- 23. Myers, F.W.H. (1886c), 127-88.

- 24. Myers (1884), 217-37.

- 25. Myers (1885a). See also Myers (1887a).

- 26. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 1, xv.

- 27. Myers (1892a); Myers (1889a).

- 28. Kelly, Kelly et al. (2007) 101-3; Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 1, 121-52.

- 29. Myers (1884-5), 114-30.

- 30. Hamilton (2009), 52-5. See also Myers (1887b), 496-514; Myers (1888b), 359-73; Myers (1888a), 374-97.

- 31. Hacking (1995), 171-82.

- 32. Williams (1984), 251-52.

- 33. Cook (1992), 69.

- 34. Myers (1892a), 298-327.

- 35. Hamilton (2013), 97-114.

- 36. Myers (1885b), 1-24.

- 37. Myers (1889c), 13-65.

- 38. Myers (1895d), 213-34.

- 39. Hamilton (2009), 129-38.

- 40. Price (1985), 25-35.

- 41. Price (1986).

- 42. Myers (1886a); Myers (1886b).

- 43. Myers (1903, 1904), xiii-xxii.

- 44. Myers & Barrett (1889); Myers (1894, 1895a).

- 45. Cassirer (1983).

- 46. Hamilton (2009), 219-21.

- 47. Hamilton (2009), 184; Myers (1893a).

- 48. Gauld (1968), 323.

- 49. Lodge et al. (1901-1903).

- 50. Collins (1948).

- 51. Hall (1968, 1980), 72-102, 103-13.

- 52. Podmore (1900–1901), 98-100.

- 53. Gurney, Myers & Podmore (1886), vol.1, xxxvii.

- 54. Myers (1892a); Myers (1892b).

- 55. Myers & Myers (1893–1894).

- 56. Myers (1892a), 301.

- 57. James, Lodge, Flournoy & Leaf (1903, 1904), 33.

- 58. Myers (1903, 1904), 222.

- 59. James (1901).

- 60. Kelly et al. (2007), 83.

- 61. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 1, xxi.

- 62. Flournoy (1911), 64.

- 63. Myers (1890), 337-8.

- 64. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 2, 198.

- 65. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 2, 31.

- 66. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 2, 182-5.

- 67. Hamilton (2009), 179-86.

- 68. Gauld (1992, 1995), 394. See also Myers (1889b); Myers (1895c), 51-8, 69-70.

- 69. Crabtree (2003).

- 70. James (1901), 1-3.

- 71. Flournoy (1911), 51.

- 72. Huxley (1961), 7-8.

- 73. Hacking(1995), 136.

- 74. Carpenter (2012), 106-7.

- 75. Taylor (2009); Assagioli (1965, 1993), 14-20.

- 76. Shamdasani (2003, 2004), 260-1.

- 77. Johnson (2006).

- 78. Hamilton (2009), 72-3.

- 79. See, e.g., Thurschwell (2001); Luckhurst (2002); Owen (2004).

- 80. Alvarado (2003); Alvarado (2009); Alvarado (2014.); Sommer (2013); Kelly (2001); Taylor (1996).

- 81. Sommer (2010); personal communication, 6 February 2017.

- 82. Ryan (2010).

- 83. Wegner (2004).

- 84. Wilson (2009).

- 85. Saltmarsh (1938, 1975).

- 86. Oppenheim (1985), 261-62, 153-55.

- 87. Hall (1964, 1968, 1980); Gauld (1964, 1965, 1966); Nicol (1966); Jarman (1964); Lambert (1969). See also Wikipedia, F.W.H. Myers.

- 88. Hamilton (2009), 287.

- 89. Kelly, E.W. (2007), in Kelly et al., 117-239.

- 90. Kelly, E.W. (2007), in Kelly et al., 232-36; Kelly, E.F. in Kelly et al., 624-25; Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 1, 134-5.

- 91. For references and a summary of the issues, see Beischel (2007).

- 92. Palmer (2012).

- 93. Myers (1903, 1904) vol. 1, xxviii.

- 94. Smith (2010), 253-55, 251-52, 238-40.

- 95. Ash et al.,(2010); Kennedy (2006).

- 96. Myers (1885b), 1-2.

- 97. Hamilton (2009), 245-72.

- 98. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 1, 588-90; Moody (1993); Radin (1997), 73-89.

- 99. Hamilton (2009), 249.

- 100. Kelly, E.W. (2007), in Kelly et al., 61.

- 101. Hamilton (2013), 97-114.

- 102. Kelly, E.F. (2007) in Kelly et al., 583.

- 103. Myers (1903, 1904), 245-56. See also Myers (1893b).

- 104. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 2, 505-54.

- 105. Kripal (2010, 2011), 37-91.

- 106. Lodge (1930), 58.

- 107. Pick (1989, 1996), 24-27, 155-75.

- 108. Myers (1903, 1904), vol. 1, 1.

- 109. Hamilton (2011).

- 110. Gauld (1968), 323-25 ; Myers (n.d.).

- 111. Lodge et al., (1901-1903), 69.

- 112. Skrupskelis & Berkeley (1994), 102-3.

- 113. Hamilton (2009), 283-8. See also Myers (1893, 1961) and Myers (1904).

- 114. Skrupskelis (2001), 66-67.

- 115. Berger (1988), 30; Blum (2006); Hamilton (2009), 56.

- 116. Cardeña & Winkelman (2011), 101-3.

- 117. Gauld (1968), 293-99.

- 118. Nicol (1972), 364.

- 119. Kelly E.F. (2007) in Kelly et al., 643.